- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: Macintosh, Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo DS, Nintendo DSi, Nintendo Switch, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: 21 Rocks, LLC, ak tronic Software & Services GmbH, Big Fish Games, Inc, Foreign Media Games, HH Games, Joindots GmbH, Micro Application, S.A., O-Games, Inc., Ocean Media d.o.o., S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, SpinTop Games

- Developer: Joindots GmbH, Ocean Media d.o.o.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Jigsaw puzzles, Mini-games, Morse code decoding, Spot the difference

- Setting: Boat, Contemporary, Ship

Description

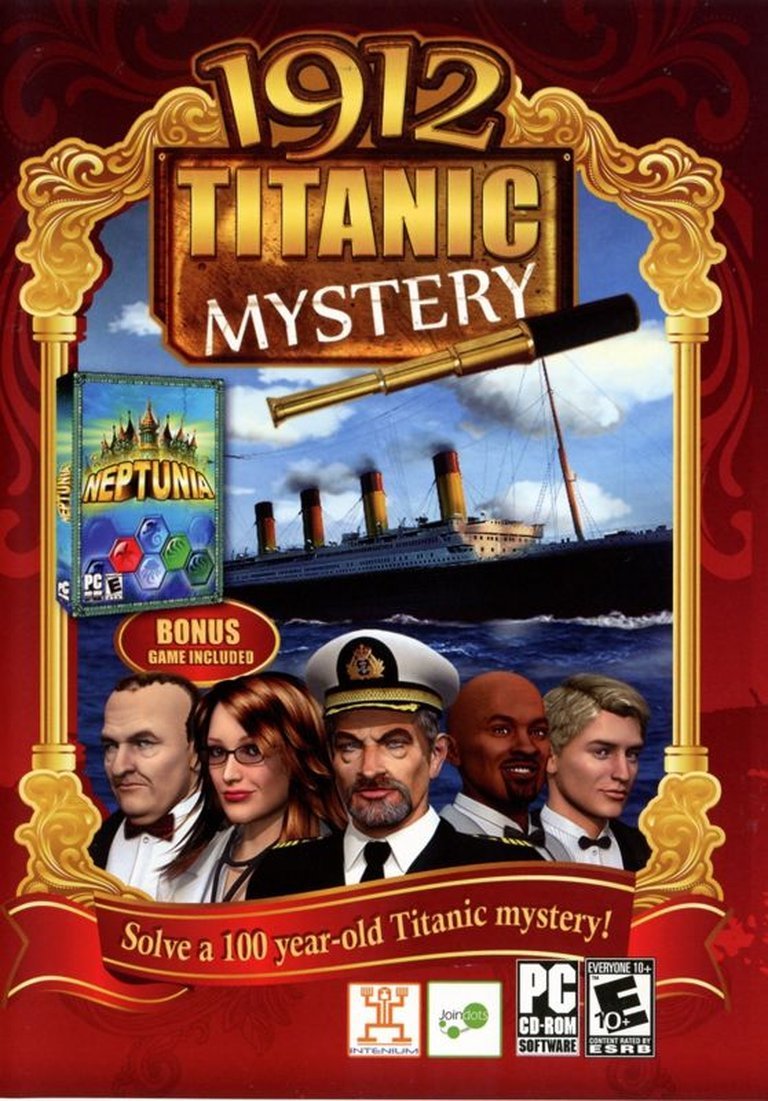

Set in 2012 on a replica of the Titanic embarking on its maiden voyage to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the original ship’s sinking, 1912: Titanic Mystery follows a passenger who discovers a cryptic note revealing a hidden bomb on board. As a hidden object adventure game, players search cluttered ship locations for items, solve puzzles, and follow clues from a terrorist to locate and disarm the device, preventing a modern-day tragedy amid the luxury liner’s opulent decks and rooms.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

1912: Titanic Mystery: Review

Introduction

Imagine stepping aboard a gleaming replica of the RMS Titanic, not in 1912 but in the modern era, where the shadow of history looms large and a ticking bomb threatens to rewrite tragedy into catastrophe. Released in 2009 to coincide with the centennial of the Titanic’s infamous sinking, 1912: Titanic Mystery from developers Ocean Media and Joindots GmbH transforms the ocean liner’s legacy into an interactive puzzle adventure. As a hidden object game with adventure undertones, it invites players to scour opulent decks for clues, blending historical reverence with contemporary suspense. This review delves exhaustively into its layers, arguing that while 1912: Titanic Mystery capably honors its Titanic muse through engaging storytelling and varied puzzles, it ultimately remains a competent but unremarkable entry in the hidden object genre, constrained by formulaic mechanics that prevent it from fully sailing into innovative waters.

Development History & Context

The development of 1912: Titanic Mystery emerged from a collaborative effort between Croatian studio Ocean Media d.o.o. and German publisher Joindots GmbH, with additional support from entities like Micro Application and Big Fish Games for distribution. Key figures included producers Jörg Henseler and Thorsten Vogt, who shaped the project’s vision alongside story contributors Jeff Hendricks and Henseler himself. The concept originated as a timely tribute to the Titanic’s 100th anniversary, reimagining the ship’s ill-fated voyage through a modern lens—a replica vessel facing a terrorist threat. This wasn’t merely opportunistic; it reflected a broader trend in the late 2000s gaming landscape, where casual puzzle games surged in popularity amid the rise of accessible PC titles from publishers like Big Fish Games.

Technological constraints of the era played a pivotal role. Launched initially on Windows in 2009 as a shareware CD-ROM or download, the game relied on standard 2D graphics engines suitable for mouse-and-keyboard input, eschewing the high-fidelity 3D modeling that would dominate later ports. The hidden object genre, booming since titles like Mystery Case Files (2002), emphasized quick development cycles and low system requirements, allowing studios like Ocean Media—known for prior adventure games such as Emily Archer and the Curse of Tutankhamun—to iterate efficiently. Art was handled by teams including Tassilo Rau and Novtilus Beijing Art Company, while programming led by Mladen Božić focused on straightforward point-and-click interactions.

The 2009 gaming landscape was ripe for such a release: the casual market exploded with hidden object adventures, fueled by the accessibility of broadband and platforms like Big Fish’s online store. Titanic-themed media, from James Cameron’s 1997 film to books like Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember, provided rich cultural fodder, but the genre’s saturation meant 1912 had to differentiate itself. Ports followed in 2010 to Nintendo DS and Wii, adapting to handheld controls, and later to Macintosh (2011), DSi/3DS (2015), and even Nintendo Switch (2021), showcasing the game’s enduring viability as a budget-friendly evergreen title. Yet, these adaptations highlighted era-specific limitations—no online features or dynamic lighting—positioning it as a product of its time, more about narrative homage than technical bravura.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, 1912: Titanic Mystery weaves a taut, self-contained plot that bridges historical reverence with modern peril, creating a narrative that’s both educational and thrilling. The story unfolds in the contemporary setting of 2012, as a passenger on a Titanic replica—launched to symbolically complete the original’s interrupted maiden voyage—receives a cryptic note revealing a hidden bomb planted by a terrorist. This setup immediately establishes stakes: prevent a new disaster echoing the 1912 sinking that claimed over 1,500 lives. Players assume the role of an unnamed investigator, piecing together clues scattered across the ship’s lavish interiors, from grand ballrooms to engine rooms, while flashbacks and notes illuminate the original Titanic’s passengers and crew.

The plot is structured episodically across multiple chapters, each progressing the investigation through environmental storytelling. Rather than a sprawling epic, it’s a linear mystery driven by discovery: early scenes build tension with the bomb’s ticking timeline, mid-game revelations tie the terrorist’s motives to historical grudges (perhaps unresolved class divides or wartime secrets from the original voyage), and the climax demands defusing the device via intricate puzzles. Characters are archetypal but effectively sketched— the wide-eyed protagonist, a suspicious captain evoking Edward Smith, and shadowy passengers representing the era’s social strata, from first-class elites to third-class immigrants. Dialogue, delivered via static text overlays, is concise and functional, laced with historical facts: players learn about real figures like John Jacob Astor or the ship’s wireless operators, interspersed with modern quips that ground the fiction.

Thematically, the game grapples with legacy and repetition, using the replica as a metaphor for humanity’s inability to escape history’s cycles. The bomb symbolizes unresolved traumas— the original Titanic as a hubris-fueled catastrophe, mirrored in 21st-century terrorism fears post-9/11. Themes of class disparity persist, with hidden objects often alluding to the era’s inequalities (e.g., luxury jewels amid steerage clutter), while the puzzle-solving mechanic underscores agency: players “right” history’s wrongs by uncovering truths. However, the narrative’s depth is uneven; dialogue can feel expository, prioritizing facts over emotional nuance, and character arcs are minimal, serving more as puzzle catalysts than fully realized portraits. Still, this restraint enhances replayability, as completed puzzles unlock a menu for revisiting historical vignettes, transforming the game into a subtle Titanic primer. In extreme detail, the story’s Morse code mini-games echo the original ship’s distress signals (CQD and SOS), thematically linking past and present in a poignant nod to communication’s role in tragedy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

1912: Titanic Mystery adheres faithfully to the hidden object genre’s core loop—search, solve, progress—while layering in adventure elements for variety, though it rarely strays from established formulas. Each of the game’s numerous scenes divides into three escalating phases: first, locate multiple instances of a single item (e.g., five keys scattered amid clutter), training observation skills; second, a traditional list of diverse objects (from teacups to telegraphs) hidden in detailed environments; third, assemble a fragmented tool (depicted as a silhouette puzzle) by collecting its pieces. This tool then activates a mini-game, such as dragging it to decode a locked panel, unlocking progression.

The mechanics emphasize precision and patience, with mouse (or touchscreen on ports) clicks revealing items amid Victorian-era bric-a-brac. Innovation shines in the mini-games, which interrupt the object hunts for intellectual variety: jigsaw reassembly of Titanic blueprints tests spatial reasoning; spot-the-difference challenges between “before” and “after” sinking images highlight subtle historical changes; Morse code decoders require inputting rhythmic dots and dashes from audio cues, evoking the ship’s real Marconi operators. These are skippable for a 10-minute penalty, catering to casual players, but encourage mastery for bonus buoys—hint icons shaped like lifesavers, limited to six and rechargeable via scene extras.

Character progression is light, tied to narrative unlocks rather than RPG elements: no leveling, but accumulating clues builds the story map, visible via an in-game journal. The UI is clean yet utilitarian—a left sidebar lists objectives, a central hint button glows invitingly, and scene transitions use smooth fades. Flaws emerge in repetition: object lists grow predictable, with occasional pixel-hunting frustrations on smaller screens like DS, where touch controls amplify misclicks. Combat is absent, as expected in a puzzle title, but the “systems” of time management (penalties for skips) and collection (replayable puzzles) add depth. Overall, the loop is addictive for short bursts—scenes last 5-15 minutes—but lacks branching paths or multiple endings, rendering it linear and somewhat shallow compared to contemporaries like Titanic: Adventure Out of Time.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world is a meticulously recreated microcosm of the Titanic, transposed to a contemporary replica, fostering an atmosphere of eerie familiarity and mounting dread. Settings span the ship’s iconic locales—opulent first-class dining saloons with crystal chandeliers, cramped third-class quarters evoking immigrant hardships, and utilitarian boiler rooms humming with latent peril—each rendered in a 1st-person perspective that immerses players as ghostly voyagers. This world-building excels in historical authenticity: objects nod to real artifacts (White Star Line crockery, period luggage), while the bomb’s presence injects modern tension, with shadowy corners and locked doors suggesting sabotage.

Visual direction, courtesy of artists like Tvrtko Kapetanović and the Novtilus team, adopts a realistic 2D style—hand-painted backgrounds with subtle parallax scrolling for depth—that captures the ship’s Gilded Age grandeur without overwhelming low-end hardware. Clutter is dense but fair, with lighting gradients (warm glows in lounges, dim flickers in holds) enhancing mood; ports like Wii add minor enhancements, though the core art remains static. This contributes to a contemplative experience, turning searches into explorations of luxury’s fragility.

Sound design, led by Damjan Mravunac, complements with a understated score: orchestral swells evoking early 20th-century elegance, interspersed with modern synth undertones for the thriller edge. Ambient effects—creaking decks, distant waves, Morse beeps—build immersion, while voice acting is absent, relying on text for subtlety. These elements synergize to evoke solitude and history’s weight, making triumphs feel like averting fate, though repetitive loops can dilute the atmosphere over extended play.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2009 Windows launch, 1912: Titanic Mystery garnered mixed critical reception, averaging 59% across five reviews, reflecting the genre’s polarized audience. Positive outlets like Adventurespiele (80%) praised its fresh story linking past and present, realistic graphics, and varied puzzles, calling it a “surprise” for Titanic fans. GamingXP (75%) highlighted its scope and value for the low price, recommending it for hidden object enthusiasts. However, GameZebo (60% for both Windows and Mac) deemed gameplay “average,” buoyed only by the narrative, while Pure Nintendo’s 2021 Switch review (60%) noted entertainment value despite “many issues” like dated controls.

The nadir came with 4Players.de’s scathing 22% for the DS port, lambasting its “cheap” design, lack of detective immersion, and uninspired puzzles that squander the bomb scenario. Commercially, it succeeded modestly as shareware via Big Fish, with used copies lingering affordably ($5-11 on eBay/Amazon), and ports extended its life, bundling it in collections like Mystery Masters. Player scores average 3.4/5 from 10 ratings, suggesting niche appeal without fervent fandom.

Legacy-wise, 1912 influences the hidden object subgenre by popularizing historical tie-ins, paving for titles like Hidden Mysteries: Titanic (2010) or Murder on the Titanic (2012). It underscores the viability of ports to consoles like Switch, keeping casual puzzles alive, but its formulaic nature limited broader impact—no genre-defining innovations, unlike Titanic: Adventure Out of Time (1996). In industry terms, it exemplifies the 2000s casual boom, influencing educational gaming by blending facts with fun, though its reputation has stabilized as a solid, if forgettable, Titanic homage.

Conclusion

In synthesizing 1912: Titanic Mystery‘s development as a anniversary tribute, its narrative bridging eras with thematic depth on history’s echoes, addictive yet repetitive hidden object loops, evocative art and sound evoking maritime grandeur, and middling reception as a genre staple, this title emerges as a respectable but not revolutionary entry. It honors the Titanic’s legacy without fully capturing its mythic scale, appealing most to puzzle aficionados seeking light adventure. Ultimately, 1912: Titanic Mystery earns a firm place in video game history as a cultural footnote—a reminder that even replicas can chart compelling, if unspectacular, courses—warranting a 7/10 for its earnest execution in a crowded sea.