- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

- Perspective: Fixed

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Pinball

Description

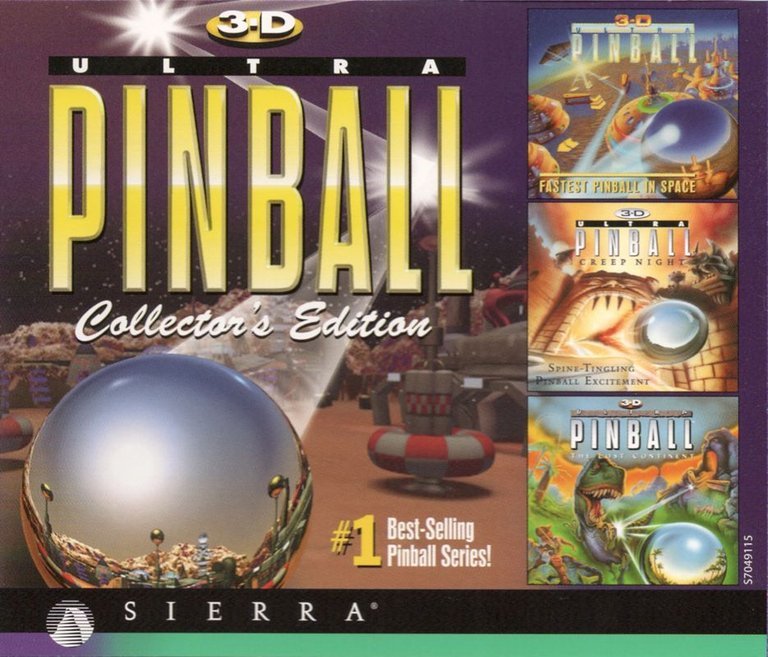

3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) is a compilation package that brings together three innovative pinball games from the 1990s: the space-themed 3-D Ultra Pinball based on the Outpost universe, the horror-inspired 3-D Ultra Pinball: Creep Night with its spooky tables, and the adventure-oriented 3-D Ultra Pinball: The Lost Continent. These games feature dynamic 3D graphics, multiple interactive tables, temporary targets like spaceships and monsters, and break from traditional pinball design, all complemented by a bonus VHS documentary titled ‘The History of Pinball’.

Gameplay Videos

3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) Free Download

3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : 3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) delivers an experience that feels like a modern take on a classic arcade pastime.

ebay.com : Oldie but goody.

3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition): A Digital Arcade Time Capsule

Introduction: The Architect of Illusion

In the mid-1990s, as 3D acceleration transformed PC gaming, a peculiar and delightful marriage occurred: the analog, mechanical soul of pinball was fused with the boundless potential of digital simulation. Sierra On-Line’s 3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition), released in 1998, stands not as a singular game but as a curated monument to a brief, vibrant era. It is a physical archive—three CD-ROMs and a VHS tape—encapsulating the entire commercial lifespan of a franchise that dared to reimagine pinball as a narrative-driven, themed adventure rather than a mere mechanical simulation. This review argues that the Collector’s Edition is a critical artifact of 1990s game preservation philosophy, a definitive package that captures both the innovative zenith and the inherent limitations of the 3-D Ultra series. Its value lies less in perfect gameplay and more in its role as a historical document, a tangible bridge between the arcade cabinet and the digital museum.

Development History & Context: Dynamix and the Sierra Experiment

The series was birthed from Dynamix, the creative powerhouse within Sierra On-Line known for genre-pushing titles like Red Baron and The Incredible Machine. Under the direction of designers like Jeff Tunnell, the studio approached pinball not as a sport but as a themed playground. The technological context was the dawn of consumer 3D graphics; Windows 95 and Mac System 7 were leveraging new APIs to render textured polygons, allowing for tables that existed in a tangible, explorable space—a stark contrast to the 2D, top-down or side-view digital pinball games of the early ‘90s.

The gaming landscape of 1995-1997 was one of genre fluidity. Sierra’s own Outpost space colony sim provided the unlikely thematic backbone for the first game. This cross-promotional synergy was common in the pre-internet era, where publishers leveraged existing IPs to give new games instant recognition. The series ran from 1995 to 2000, and the Collector’s Edition (1998) arrived at a pivotal moment: the tail end of the CD-ROM “golden age,” just before online distribution and engine standardization would make such bespoke compilations obsolete. Its development thus represents a last gasp of the premium, physical collection—a strategy to maximize the value of a fading franchise by bundling its complete run with a proprietary bonus (the VHS documentary), a tactic echoing today’s “Game of the Year” editions.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: From Space Colonies to Spooky Castles

The genius of the 3-D Ultra series was its diegetic integration of narrative. Pinball’s traditional score-attack mode was框架ed within loose, engaging stories, transforming the playfield into a stage for cinematic vignettes.

- 3-D Ultra Pinball (1995): The Colonization Narrative. Set within the universe of Sierra’s Outpost, the game’s narrative is one of struggle and construction. The three tables—Colony, Command Post, Mine—represent stages of establishing an extraterrestrial foothold. The player’s goal to “build and launch a starship” provides a through-line, but the narrative is delivered through environmental storytelling (crumbling structures, holographic maps) and challenge completion (activating systems, gathering resources). It’s a story of human ingenuity against a hostile void, perfectly mirrored by pinball’s tension between control and chaos.

- 3-D Ultra Pinball: Creep Night (1996): Horror Comedy as Menu. This entry fully embraces a pastiche of classic horror tropes. The Castle, Tower, and Dungeon tables are not just settings but narrative zones within a haunted estate. Challenges have explicit story hooks: “Zombies” swarm the playfield, a “Runaway” goblin on an ATV is a chaotic chase sequence, and “Wraith” is a magnetic specter with agency. The narrative is interactive and reactive; hitting the “Frankenstein monster” five times after completing the Tower table is a literal boss fight. The tone is self-aware, campy, and engaging, using pinball’s frantic pace to mimic the pacing of a haunted house attraction.

- 3-D Ultra Pinball: The Lost Continent (1997): The Adventure Serial. This is the series’ most ambitious narrative venture, directly competing with Jurassic Park. The story of Professor Spector, Mary, Rex Hunter, and Neeka trapped on an island with the villainous Heckla and his robotic dinosaurs is told through full-motion video (FMV) cutscenes and table animations. The 16 tables across the Jungle, Temple, and Chambers sectors act as “chapters” in an escape ordeal. Hitting targets triggers plot points—awakening a robot, rescuing a tribeswoman—making each game a progressive story unlock. The narrative is linear and goal-oriented, a significant departure from the open-ended score-chasing of traditional pinball.

These narratives are not complex, but they are effective scaffolding, elevating each ball launch into a step in an adventure. They utilize the medium’s strengths: immediate feedback and visual spectacle to convey plot.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Innovation Within Constraints

The core innovation of the series was the “temporary target” system, as noted on Wikipedia. Unlike static pinball machine targets, these were dynamic, scripted events: a spaceship zooms across the screen, a goblin pops up, a boulder rolls. These required precise timing and shot-making, actively engaging the player’s reaction skills beyond standard flipper timing. Each table featured “mini-tables”—sub-sections with their own flippers—that broke the monotony of a single-plane layout.

- Gameplay Loop: The loop was elegantly simple: complete five “challenges” per table (in the first two games) to unlock the next table or a final “boss” mode. This provided a clear progression system absent from pure arcade ports. In The Lost Continent, this evolved into a sector-based exploration, where completing tables in one zone opened another, creating a sense of discovery.

- Physics and Controls: The physics were a calculated abstraction. As Next Generation noted, they included “elements not possible on a real pinball table” (like magnetic balls, impossible ramps) while remaining “true to the pinball spirit.” The controls were keyboard-based (or mouse-click flippers), reliable but lacking the analog nuance of a real cabinet. The “tilt” mechanic was present but felt less physical and more like a penalty timer.

- Flaws: The infamous “stutters” cited by the Macworld review were a critical flaw. This was a period of intense hardware fragmentation; the game’s 3Dpolygons and animations could tax late-‘90s integrated graphics, causing frame-rate dips that directly impacted the ball’s perceived physics and timing. This broke the immersion and fairness the simulation sought. The table length criticism is also valid; compared to the marathon sessions of a physical table or even Pro Pinball, these felt like brisk, thematic episodes rather than endless endurance tests.

UI & Menus: The interface was clean, with a 3D-rendered scoreboard and mission status clearly visible. The main menu presented the three games as distinct “cartridges” within the compilation, reinforcing the collection’s physicality.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Thematic Triptych

The visual and audio design was where the series’ identity truly coalesced, with each game defining a distinct aesthetic universe.

- 3-D Ultra Pinball: A bright, optimistic sci-fi aesthetic. Tables were awash in blues, purples, and metallics, with wireframe outposts and neon warp gates. The sound design featured synthesized engine hums, laser blasts, and a triumphal, MIDI-based score that evoked Star Trek more than Alien. The world felt clean, technological, and hopeful.

- Creep Night: Masterful horror ambiance. This was the series’ stylistic peak. Tables used dark palettes, fog effects, flickering lights, and cobweb-covered textures. The audio was a collage of creaky doors, howling winds, ghostly moans, and a campy, theremin-heavy soundtrack. Animated ghosts and monsters provided jump-scares and humor. The art direction fully committed to the theme, making the playfield feel like a living, spooky set piece.

- The Lost Continent: A Primeval Adventure aesthetic, directly channeling Jurassic Park. Lush, textured jungle environments, ancient stone temples, and cavernous labs. The soundscape was dense with dinosaur roars, tribal drumming, insect chirps, and the clank of Heckla’s machinery. The use of pre-rendered FMV backdrops and animated dinosaur sprites attempted (with late-‘90s limitations) to create a cinematic, blockbuster feel.

The Soundtrack: Composed of adaptive MIDI tracks that changed intensity based on gameplay state (normal play, multiball, ball lost). They were catchy and thematic but often repetitive, a common limitation of the format.

The VHS Documentary: The History of Pinball is the collector’s pièce de résistance. For a 1998 audience, this 60-minute film was a revelation—a serious, archival look at pinball’s mechanical evolution from the 1930s to the 1990s, featuring interviews with designers and footage of classic tables. It provided crucial context and legitimacy, positioning the digital game not as a replacement but as the latest chapter in a long tradition. It’s the element that most firmly cements the package as a historical artifact.

Reception & Legacy: Critical Divide and Cult Status

Critical Reception: It was mixed to poor, as the MobyGames aggregate (40% from a single critic) and the Macworld review (2/5 stars) indicate. Critics often cited the very flaws that define the package: unrealistic physics, short tables, and performance issues. Next Generation’s paradoxical 2/5 review—praising its spirit while panning the score—captures the divide. It was appreciated for its ambition but not embraced as a serious simulator. The PC Gamer 86% score for the original 1995 release shows the potential was recognized, but the compilation format diluted that initial enthusiasm.

Commercial & Fan Legacy: The series sold over 500,000 copies by 1998 (per the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette), indicating strong, if not blockbuster, success. The Collector’s Edition itself is now a cult object. Its value to collectors is twofold: it’s the most complete archival package of the series, and it includes the increasingly rare VHS documentary. The eBay listing (and the one user review) reveals a community that views it nostalgically as a “goodie” and a piece of Sierra history, even if they warn of compatibility issues with modern Windows.

Influence: Its direct influence is subtle. The “themed table as adventure” concept found echoes in later pinball games like Pinball Hall of Fame: The Williams Collection (which prioritized historical accuracy) and Zen Pinball (which uses licensed IPs for narrative tables). More broadly, it exemplified the “compilation as preservation” model that companies like Activision (via the Sierra 3D Ultra re-releases) and later, digital storefronts would adopt. It also stands as a late example of cross-media bonus content (the VHS), a practice now largely limited to “collector’s editions” with artbooks and soundtracks.

Conclusion: A Flawed, Fascinating Relic

3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) is not the pinnacle of pinball simulation. Its physics are loose, its tables are short, and its performance is archaic. Judged on pure gameplay, it cannot compete with the forensic detail of Pro Pinball or the robust physics of modern titles.

However, judged as a historical package, it is exceptional. It is a time capsule of Sierra’s late-90s output: a compilation that bundles software with a physical media documentary, all housed in a jewel case with printed manuals. It documents the creative journey of a studio (Dynamix) at the intersection of practical simulation and themed entertainment. Its narrative experiments—turning pinball into a space colony sim, a horror comedy, and a Jurassic Park adventure—show a willingness to push the genre’s boundaries that is rare today.

The definitive verdict is this: 3-D Ultra Pinball (Collector’s Edition) is a must-own for historians and collectors of 1990s PC gaming, and a curious, charming diversion for pinball fans. It is flawed, sometimes frustrating, but utterly distinctive. It represents a specific moment when game publishers had the ambition and margin to create elaborate, cross-media packages for niche genres. Its true high score is not on the leaderboard, but in its role as a preserved artifact—a plastic CD case containing the audible ghost of the pinball machine’s future, as imagined in the brief, bright summer of 3D acceleration.