- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Soft & Fun

- Genre: Gambling, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tiles

Description

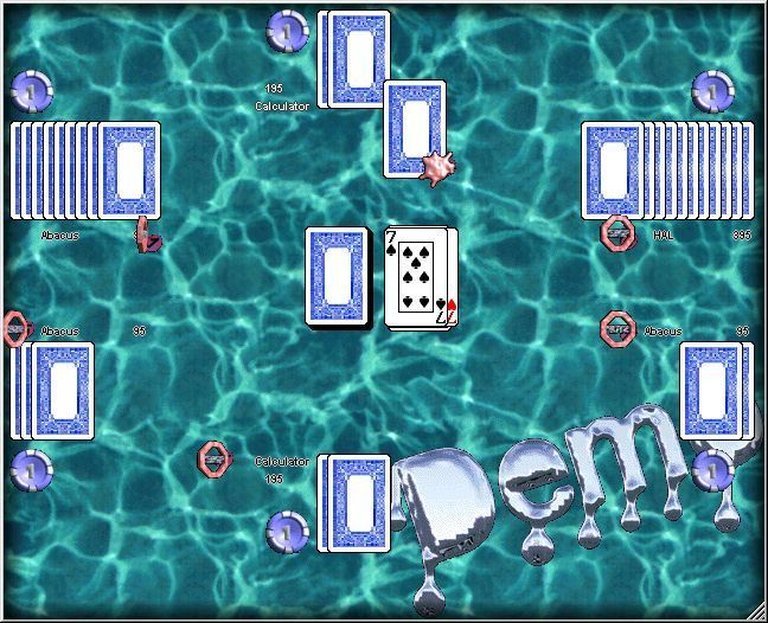

4Flush is a shareware video game collection from 1999 that compiles a wide range of card games, including numerous poker variants, classic titles like Blackjack and Mau-Mau, and various solitaire games. Players can compete against the computer or others online in casino-style modes for points or virtual cash, with customizable card designs, backgrounds, and multilingual support in English, German, Norwegian, and Dutch.

4Flush Reviews & Reception

reddit.com : This feeling is both luxurious and full of atmosphere

4Flush: Review

Introduction: The Last Ace in the Shareware Deck

In the waning days of the 1990s, as the industry collectively gazed toward the shimmering promise of 3D graphics and persistent online worlds, a quiet revolution was unfolding in the realm of casual PC gaming. It was an era defined by ambitious narrative epics, groundbreaking 3D engines, and the nascent smells of dial-up modem connections. Yet, tucked within the shareware catalogs and bundled CD-ROMs that saturated computer magazines and software aisles, a different kind of game thrived: the comprehensive, no-frills card game collection. 4Flush, developed by the prolific German solo developer Stefan Kühne under the Soft & Fun banner and released on March 14, 1999, stands as a magnificent, if overlooked, monument to this specific moment. It is not a game that defined a generation, but one that perfectly served a generation—a digital pocket casino and solitaire parlor for the Windows 95/98 masses. This review argues that 4Flush’s historical significance lies not in revolutionary mechanics or narrative depth, but in its breathtaking scope, its embodiment of the shareware ethos, and its role as a curative antidote to the era’s escalating complexity. It is a masterclass in compilation, accessibility, and silent ambition, representing the final, confident flowering of a genre that would soon be commodified and overshadowed by online gambling giants.

Development History & Context: A Solo Developer’s Grand Design

To understand 4Flush, one must first understand its creator and its context. The game was developed by Stefan Kühne, credited on MobyGames as the sole developer for the Windows version under the studio moniker Soft & Fun. Kühne was a remarkably prolific figure in the German and European shareware scene, with credits on at least five other titles according to his Moby profile. His specialty was clear: accessible, often card- or puzzle-based games that catered to a broad, non-hardcore audience. 4Flush represents the zenith of this focus—a massive, meticulously assembled compilation that feels less like a collection and more like a definitive toolkit.

The game emerged in 1999, a watershed year documented in sources like the History of Video Games/1990-1999 Wikibook. This was the year of Soulcalibur, Final Fantasy VIII, Silent Hill, and the launch of the Sega Dreamcast. The industry’s narrative was one of technological leaps: 3D graphics were becoming photorealistic, online play was moving from novelty to expectation (with EverQuest and Counter-Strike mods altering multiplayer landscapes), and storytelling in games was reaching new cinematic heights. Against this backdrop of “more is more” development, 4Flush’s development philosophy was almost defiantly conservative. It required no cutting-edge 3D accelerator, no expansive voice cast, no sprawling narrative team. Its constraints were the constraints of the universal Windows API and a mouse-driven interface. Yet, within those constraints, Kühne’s vision was one of completeness. The game was built in an era when “shareware” was still a viable business model—a fully functional but limited version distributed freely to entice a purchase of the full “registered” package. 4Flush executed this model with classic precision: the shareware version was not a demo, but a crippled full game, offering only two poker variants (Draw Poker and Five Card Stud), a single-bet Blackjack, and a few incomplete Crazy 8’s rules, tantalizingly hinting at the 60+ other games locked behind the registration barrier.

The gaming landscape of 1999 was also one of fragmentation and consolidation. While consoles battled for supremacy, the PC was a wild west of genres. Card and board game adaptations were a staple of the “edutainment” and casual market, but rarely with 4Flush‘s sheer taxonomic dedication. It didn’t just offer “Poker”; it offered Twenty-six distinct poker variants, from the familiar (Hold-em, Omaha) to the arcane (Lamebrain Pete, Spit in the ocean). This speaks to a developer who understood the deep, regional, and cultural specificity of card gaming, targeting a European audience (hence multilingual support in English, German, Norwegian, Dutch) with games like Bauernskat and Doppelkopf that were largely unknown in the Anglo-American mainstream.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of Chance and Choice

4Flush is, by its very nature, a non-narrative experience. It possesses no plot, no characters, no dialogue trees, or thematic lore. Its “story” is the eternal, silent drama of the card shuffle, the gamble, and the strategic calculation. Therefore, a traditional narrative analysis is inapplicable. Instead, we must examine its thematic and philosophical underpinnings, which are intrinsically tied to the nature of card gaming itself.

The core theme is Agency vs. Chance. Every game within 4Flush is a delicate negotiation between the player’s strategic mind and the brutal randomness of the deck. In a game of Seven Card Stud HiLo, the player’s agency lies in reading opponents (the AI), calculating pot odds, and deciding when to fold or raise. Yet, the ultimate outcome is dictated by the next card turned—a pure stochastic event. This mirrors the fundamental human condition of making consequential choices within a framework of uncontrollable luck. The game’s title, 4Flush, is itself a poker term for a hand with four cards of the same suit, one card away from a flush. It’s a state of potent possibility and agonizing incompletion, a perfect metaphor for the player’s perpetual state: always one card, one decision, away from triumph or ruin.

The collection also implicitly thematizes Cultural Preservation. By including such a vast array of regional and historical variants—from German Doppelkopf to the solitaire family’s global iterations (Pyramid, Golf, Tut’s Tomb)—4Flush functions as a digital archive. In an era increasingly focused on new IPs and cinematic universes, this was a quiet act of curation, preserving niche game rules that might otherwise fade in the face of ubiquitous Texas Hold’em. The customizable card designs and the ability to use a personal photograph as a card symbol further personalizes this archive, allowing the player to insert their own visage into this timeless cycle of wins and losses, blurring the line between the game’s historical mechanics and the player’s immediate experience.

Finally, the Casino Mode introduces a layer of simulated economic theme. Playing for “virtual cash” against the house transforms these abstract games into a simulation of risk capitalism. The player’s “bankroll” becomes a tangible measure of success and failure, introducing a psychological pressure absent from the pure “points” mode. It’s a safe, consequence-free simulation of the high-stakes environment, a theme deeply resonant in the late ’90s, a period of economic boom preceding the dot-com crash.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Ultimate Card Table

4Flush’s genius is in its organizational comprehensiveness and flawless, minimalist execution. The entire interface operates within a fixed-size window, controlled entirely by the mouse, a design choice that prioritizes clarity and accessibility over flashy visuals. This uniformity is its strength; whether playing Omaha HiLo or Pyramid solitaire, the user experience is consistent and intuitive.

The game is structurally split into two primary pillars:

-

Poker & Banking Games: This is the headline attraction. The full version includes an astonishing 26 poker variants, meticulously categorized. They range from:

- Stud Games: Five, Six, Seven, and Eight Card Stud, all with HiLo (split pot) variants.

- Draw Games: The foundational Draw Poker and its numerous mutators (Jackpots, Pass & Out, Lowball).

- Community Card Games: The ever-popular Hold-em and Omaha, both with HiLo splits.

- Obscure & Novelty Games: Shotgun, Spit in the Ocean, Cincinnati, Criss Cross, Lamebrain Pete, and Hurricane. These are not just reskins but games with genuinely different hand-making rules and betting structures, appealing to the aficionado.

- Specialty: Three Card Poker and Two Card Poker offer faster, simpler actions.

Beyond poker, Blackjack is present in a basic form, and the inclusion of Mau-Mau and Crazy 8’s & Crazy Jacks covers the popular German/European family game niche (though the shareware version of Crazy 8’s lacks some implemented rules, a telling detail about the shareware/retail split).

-

Solitaire & Patience Games: The collection doubles as a solitaire suite, featuring 15 distinct games: Solitaire (Klondike), Butterfly, Tut’s Tomb, Tri Peaks, 8 Stacks, Icebreaker, Pyramid, Golf, 5×5, Square, and 13. This selection covers the spectrum from classics (Klondike) to more modern, triangular layouts like Pyramid and Golf, ensuring longevity for solo players.

Core Systems:

* Dual Mode: All games can be played for Points (a high-score chase) or in Casino Mode (with virtual cash, simulating a gambling floor).

* AI Opponent: Games are played “against the computer.” The quality of the AI is not documented in sources, but for a shareware product of this era, it was likely competent but not supremely challenging, designed for recreation over serious competition.

* Internet Play: The description mentions playing “against other players via the internet.” However, no technical details are provided. In 1999, this likely meant a primitive, direct-IP or lobby-based system, possibly using a proprietary protocol or early Microsoft Gaming Zone compatibility—a feature that was more ambitious than most contemporary shareware card games but would feel archaic today.

* Customization Suite: This is where 4Flush transcends mere compilation. It includes a Card Design Function, allowing players to create custom card backs and faces. Most strikingly, it allows the use of “your own picture as a symbol within the game”—a feature that let players insert their own portraits as the “face cards” (Jacks, Queens, Kings), a charmingly personal touch rarely seen even in modern games. Coupled with custom background wallpapers, this level of personalization was exceptional for its time and class.

* Multi-Language Support: The UI and game text can be switched between English, German, Norwegian, and Dutch. This was a significant logistical effort for a one-person studio and cemented its appeal in Northern Europe.

Flaws & Innovations: The major “flaw” is inherent to its business model: the shareware version is a crippled tease. The incomplete rules for Crazy 8’s in the shareware version are a deliberate friction point. Its innovation is its totality. It does not try to reinvent card game rules; it seeks to be the definitive digital repository for them. Its fixed-window, mouse-only interface was a masterclass in functional, cross-platform design that would work on any Windows PC of the era without hardware concerns.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of the felt Table

4Flush presents a world not of sprawling cities or alien planets, but of the green felt tabletop. Its artistic direction is one of utilitarian clarity. The perspective is strictly top-down, mimicking the view of a real card table. There is no attempt at 3D card models or elaborate animations. Cards are 2D sprites, cleanly rendered and easily readable. The focus is 100% on game state visibility.

The visual design prioritizes:

1. Legibility: Card suits and ranks are large and clear. The table surface is a neutral, high-contrast color ( typically green or blue) to make cards pop.

2. Consistency: Across all 40+ games, the core UI elements (betting controls, score displays, action buttons) are placed identically. Learning one game’s interface teaches you them all.

3. Customizability: As noted, the player can radically alter the visual experience by uploading custom card graphics and backgrounds. This transforms the sterile default table into a personal space. A player could, for example, use family photos as card faces, making a game of poker feel like a surreal, intimate gathering.

The sound design is functional and minimal, as was standard for shareware titles. It likely consists of basic digital sound files for:

* Card shuffling and dealing.

* A simple chime for winning a hand.

* A low buzz for an error or loss.

* Perhaps a loopable, unobtrusive MIDI track for ambiance.

There is no voice acting, no dynamic soundtrack. The soundscape is that of a quiet,专注 personal gaming room. This austerity works in its favor; it never distracts from the core mechanics.

The atmosphere is one of quiet, solitary concentration or friendly, low-stakes competition. There is no casino hype, no crowd cheers, no cinematic tension. The world is the game state. This makes 4Flush a uniquely meditative or intensely strategic experience depending on the game chosen, entirely devoid of the sensory overload of its contemporaries like Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater or Soulcalibur. It is the gaming equivalent of a well-worn deck of cards on a kitchen table.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Giant of the Shareware Era

Critical Reception at Launch:

Upon its release in March 1999, 4Flush existed in a media ecosystem largely uninterested in comprehensive card game collections. Mainstream gaming magazines (like PC Gamer, Computer Gaming World) were focused on covering the year’s blockbuster RPGs, shooters, and strategy titles. MobyGames, our primary source, shows zero critic reviews for the title and only 2 players who have “collected” it as of 2023. Its user rating on VGTimes is a modest 3.0/5. This indicates it was a deeply niche, obscure product, known primarily to shareware finders and fans of German-developed casual games. It would have been reviewed, if at all, in the back pages of German PC magazines or in aggregated shareware catalogs.

Commercial Performance:

As shareware, its success was measured in registration fees. Its vast scope was its primary sales pitch. The model was proven: give players a substantial but limited taste (two poker games, one Blackjack bet), and convince them that the full 60+ game package was worth the fee (likely in the $20-$30 range). Its inclusion of region-specific games like Bauernskat suggests it found its strongest market in German-speaking countries. Exact sales figures are lost to history, but its continued presence on MobyGames with multiple platform entries (Windows, PC-98—though the PC-98 entry is a different game, the 1993 visual novel) suggests it sold modestly but consistently over time through shareware channels and bundled CD-ROMs.

Evolution of Reputation & Influence:

Today, 4Flush is a historical footnote, but a significant one.

* As a Curio: It is a fascinating artifact of the pre-internet, pre-Steam, pre-app-store era of PC gaming distribution. It represents the peak of what a dedicated shareware developer could package and distribute independently.

* On Card Game Digitalization: It stands as one of the most comprehensive digital implementations of tabletop card games before the era of online gambling sites (like PokerStars) and streamlined digital adaptations (like Hearthstone). It treated card games with the seriousness of a simulation, offering rules and variants with scholarly depth.

* On Game Design Philosophy: It is a counterpoint to the industry’s push toward ever-greater complexity. 4Flush’s complexity is horizontal (many simple games) rather than vertical (one game with immense systemic depth). This philosophy would later find a home in the “casual” and “social” game markets on platforms like PopCap and mobile app stores, though rarely with such taxonomic rigor.

* The “Other” Four Flush: It is crucial to distinguish this 1999 card collection from the entirely unrelated 1993 PC-98 visual novel Four Flush (also by Agumix), a cyberpunk eroge with a narrative about an assassin in a dystopian megacity. The name collision is a curious piece of gaming trivia, but the two products share no DNA. The 1993 game represents the narrative, anime-infused side of early ’90s Japanese PC gaming, while the 1999 game represents the mechanic-focused, European shareware tradition. Their shared name is likely a coincidence based on the poker term.

Its legacy is not one of direct sequels or modern revivals. Instead, it is a baseline. Any modern card game compilation—whether from Microsoft Solitaire Collection or a dedicated casino suite—is measured against the sheer volume and variety that 4Flush offered two decades earlier. It proved there was a market for “everything,” not just “the most popular.”

Conclusion: A Royal Flush of Pragmatism

4Flush is not a game that will elicit passionate debates about its story or revolutionize how we play. It will not appear on “Best Games of All Time” lists like those from 1999 that canonized Soulcalibur, Planescape: Torment, and System Shock 2. Its place in history is quieter, but no less firm. It is the definitive digital card shop of the late 20th century—a meticulously curated, functionally flawless, and ambitiously scoped toolkit that celebrated the timeless appeal of cards in an age obsessed with the new.

Stefan Kühne and Soft & Fun did not set out to make a statement about the future of interactive entertainment. They set out to make the best, most complete card game compilation possible for the Windows desktop. In that goal, they succeeded triumphantly. 4Flush is a monument to the power of scope and accessibility, a game that understands its purpose is to be used, not merely beaten. It is a game for the quick break between work tasks, for the long Sunday afternoon, for the friendly wager with a remote opponent. In an industry perpetually chasing the next big thing, 4Flush is a proud, unassuming testament to the enduring power of the old thing—done so completely that it leaves no room for improvement. Its Moby score may be “n/a,” but its historical value is, in its own niche, a perfect 10.