- Release Year: 2018

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Raxasoft Games

- Developer: Raxasoft Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Run-and-gun, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

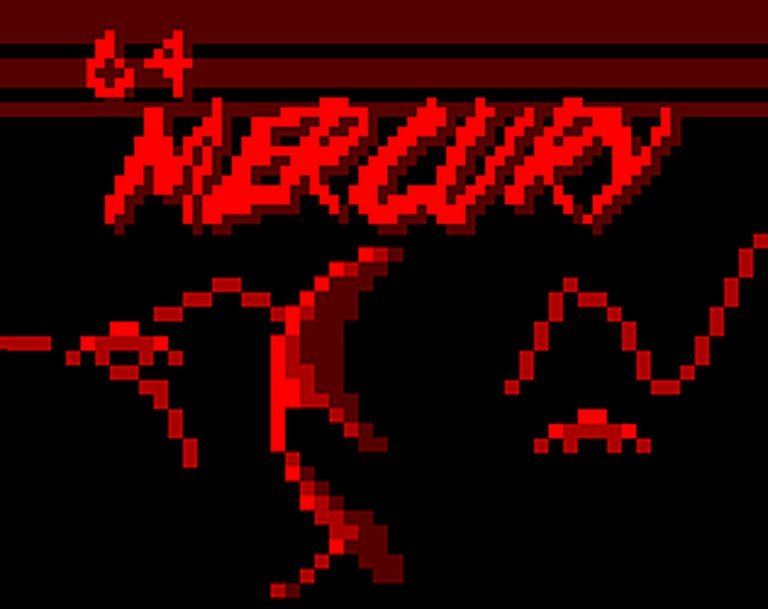

64 Mercury is a free, short side-scrolling run-and-gun game set in a sci-fi future where players must single-handedly combat the invasive Mercury creatures. As a demake of Project Mercury, it features three compact levels inspired by the original, including pit-filled platforming, hoverbike segments, and a descent into a deep hole ending with a boss battle against a giant insect, all rendered in a retro 8-bit handheld aesthetic.

64 Mercury: A Minuscule Masterpiece of Constraint and Homage

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast, overcrowded archives of video game history, some titles exist not as monolithic landmarks but as exquisite, fleeting footnotes—games so tightly bound to a specific moment, toolset, or philosophy that they become crystalline artifacts of their creation context. 64 Mercury is one such artifact. Developed by the singular effort of Raxasoft Games and released as a submission for the 2018 #LOWREZJAM, it is a “demake” of the obscure 2017 title Project Mercury. Yet, to label it merely a “demake” is to miss its profound, albeit miniature, significance. 64 Mercury is a masterclass in constraints-driven design, a love letter to 8-bit aesthetics that paradoxically leverages 21st-century tools to evoke the spirit of a bygone era. Its legacy is not one of sales charts or cultural saturation, but of pure, distilled game design philosophy. This review argues that 64 Mercury stands as a vital, if overlooked, case study in how modern indie development can channel the creative scarcity of the past to produce experiences of surprising depth and nostalgic resonance, serving as a conceptual bridge between the 2D precision of classic platforming and the nascent 3D experimentation of the Nintendo 64 era—a era famously defined by its opposite, the revolutionary Super Mario 64.

Development History & Context: Birth in the Jam Trenches

The entire documented history of 64 Mercury is contained within two poignant facts: its creation for #LOWREZJAM 2018 and its construction using Clickteam Fusion 2.5. The #LOWREZJAM is a game jam with a deceptively simple yet brutally restrictive rule: all entries must run at a resolution of 64×64 pixels, with upscaling permitted only for display. This constraint forces developers to abandon the visual fidelity of modern gaming and return to the fundamental, symbolic language of pixel art. Every sprite, every UI element, every animation must be carved from a mere 4,096 pixels.

Raxasoft Games, a studio with a footprint barely larger than the game itself, embraced this constraint not as a limitation but as a creative crucible. The choice of Clickteam Fusion 2.5—a direct descendant of the Klik & Play and Multimedia Fusion engines that birthed countless iconic indie and “bedroom” games in the late 90s and 2000s—is deeply symbolic. This engine’s event-based, no-code-required logic mirrors the minimalist, direct-control ethos of 8-bit and 16-bit development. There are no sprawling, proprietary C++ codebases here; there is a logical sheet of events and conditions, a direct digital descendant of the physical wiring and soldering that once defined arcade boards.

The game’s existence as a “demake” of Project Mercury places it within a fascinating subgenre: the retro reinterpretation. While most demakes seek to recapture a 3D experience in 2D (e.g., Mega Man X3 demakes), 64 Mercury’s source material, Project Mercury, appears to be a modern title itself (released 2017). This creates a unique temporal loop: a 2018 game, using a 1990s-era toolset inspired by 1980s hardware limitations, reinterpreted a 2017 game, all filtered through the aesthetic of a hypothetical 1996 Nintendo 64 title. The Nintendo 64’s actual visual identity—a hybrid of 2D sprites and low-poly 3D models, jutting into the new millennium—is evoked not by technical mimicry but by stylistic shorthand: the “vaguely 8-bit handheld style” noted on MobyGames reads less like a Game Boy and more like a Virtua Boy fantasy, where simple, blocky shapes and limited color palettes suggest a world seen through the foggy lens of early 3D rasterization.

The gaming landscape of 2018 was one of abundant resources. High-resolution textures, physics engines, and online connectivity were norms. Against this backdrop, 64 Mercury‘s submission to a low-resolution jam is a deliberate act of aesthetic rebellion. It channels the same spirit that drove developers on the original Nintendo 64 to innovate within tight memory limits (cartridges could hold only 4-64 MB, vs. CD-ROM’s 650+ MB), but here the constraint is self-imposed and artistic, not technological. Its development context is its thesis: great game design is born from restriction.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Silence of Invasion

64 Mercury presents a narrative skeleton stripped to its absolute essentials, a stylistic choice that perfectly aligns with its minimalist aesthetic. The official description states: “The creatures known as Mercury have invaded the area, and you alone must take them out.” This is not a story; it is a premise. There is no exposition, no cutscenes, no dialogue. The player is dropped into the action with the immediate, primal objective of a classic arcade shooter: destroy the threat.

The thematic weight lies in what is not said. The “creatures known as Mercury” are never explained. Are they aliens? Monsters from a failed experiment? A metaphor for pollution or disease? The ambiguity is potent. The player is an unspecified protagonist (the MobyGames specs note a “Female Protagonist” tag on itch.io, a detail absent from most other sources, adding a subtle but notable layer to the “you alone must take them out” equation). There is no princess to rescue, no kingdom to save—only an “area” to cleanse. This isolates the act of gameplay into a pure, almost existential struggle. The “invasion” is not a plot device to motivate a quest; it is the entire world’s state.

This narrative vacuum forces the player to project meaning onto the gameplay itself. The three distinct level types—a “pit-filled side-scrolling section,” a “hoverbike section,” and a “trek down a deep hole ending with a boss battle against a giant insect”—suggest a campaign of escalating desperation. It begins with straightforward ground combat, transitions to high-speed vehicular evasion and attack, and culminates in a claustrophobic descent into the literal and figurative heart of the invasion, facing a “giant insect.” The insect boss is the only named narrative entity; its scale and form imply it is the source or general of the Mercury horde. The journey is one of progressive penetration, from surface skirmishes to the lair of the beast. The theme is one of solitary, relentless attrition against an unknowable, pervasive enemy—a potent echo of classic sci-fi horror like They or The Blob, told through the language of a 30-second-level-run.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Precision in a Tiny Frame

The genius of 64 Mercury is how it maximizes its extreme resolution and short length to create a tight, varied gameplay loop. The game is explicitly described as a “short side-scrolling run-and-gun,” a genre with a hallowed pedigree from Contra to Metal Slug. However, its three-level structure introduces deliberate, jarring shifts in gameplay modality, each serving as a distinct “stage” in the micro-campaign.

1. The Pit-Filled Side-Scroller (Level 1): This is the purest expression of the run-and-gun core. The “pit-filled” descriptor is key—level design here is about verticality and risk. The 64×64 resolution means platforms and hazards are necessarily chunky and readable. The player must master precise jumps over bottomless pits while engaging stationary or slowly patrolling “Mercury” creatures. The controls are “direct” (per Moby specs), implying no complex combat systems—likely a simple shoot button, perhaps with limited ammo or a spread shot. The challenge is spatial awareness and pacing in a confined, scrolling space. This level establishes the core risk/reward: aggressive forward movement to score points or clear enemies versus cautious platforming to survive.

2. The Hoverbike Section (Level 2): This is the game’s most innovative twist. The “vehicular” spec tag and “hoverbike” description indicate a transition to a high-speed, laterally scrolling shooter akin to Sonic the Hedgehog’s special stages or Galaxy Force. The hoverbike likely controls differently from on-foot Mario—faster, with momentum, perhaps with a fixed forward trajectory where the player only controls altitude and firing angle. This section tests reflexes and pattern recognition against faster, more aggressive projectile enemies. The shift from the deliberate, jump-based platforming of Level 1 to the twitch-based evasion of Level 2 is the game’s primary mechanical “story,” showcasing the versatility of the “Mercury invasion” threat.

3. The Deep Hole & Insect Boss (Level 3): The final stage is a hybrid. The “trek down a deep hole” suggests a vertically scrolling descent, possibly with crumbling platforms or environmental hazards (falling rocks, rising fluids). This section builds tension and weariness, stripping away the speed of the bike for a slow, perilous climb down. It culminates in the “giant insect” boss. Given the low-poly, 8-bit style, this boss likely has a simple, repeating attack pattern with telegraphed weak points. The fight probably requires the player to utilize all skills learned: precise jumping to avoid wide sweeps, shooting at exposed segments, and perhaps using the environment (the hole’s walls for cover). The “trek down” implies a return trip after the boss falls, creating a satisfying full-circle journey.

Systems & UI: The resolution dictates an ultra-minimalist HUD. Health, ammo, score—these must be represented by a few pixels. The “Direct control” interface suggests no complex menus; the game is likely entirely diegetic or uses a minuscule, non-intrusive overlay. The lack of a documented “character progression” system (no power-ups, no skill trees) confirms that 64 Mercury is a pure arcade experience. Mastery comes from player skill, not stat inflation. The game’s brevity (three levels) means any “progression” is conceptual and experiential, not numerical.

Innovation vs. Flaw: The innovation lies in the diversity of core gameplay within a 64×64 frame and ~15 minutes of estimated playtime. It’s a sampler platter of run-and-gun mechanics. Its potential flaws are inherent to its jam nature: limited enemy variety (likely 2-3 types per level), no difficulty settings, and a single, short campaign. What looks like a lack of content is, in context, a virtue—it is a perfectly formed, disposable gem, not an unfilled promise.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Absence

64 Mercury‘s world is not built; it is suggested. The “vaguely 8-bit handheld style” and “sci-fi / futuristic” setting fuse to create a unique visual language. Imagine a Game Boy Color palette pushed to an extreme: limited to maybe 4-5 colors on screen at once, with stark black outlines defining everything. The “Mercury” creatures are probably simple, alien shapes—blobs, iridescent insects, geometric menaces—their threat conveyed through animation (a shudder, a lunge) rather than texturing. The environments are iconic silhouettes: the pit is just a chasm with jagged edges; the hole is a tunnel descending into absolute black; the sky of the hoverbike level might be a single-color gradient with star pixels.

This extreme minimalism is a powerful tool. The “deep hole” is not a textured mine shaft; it is darkness. The player’s imagination fills the void, making the descent more unnerving than any detailed model could. The “giant insect” boss is not a photorealistic monster; it is a collection of threatening pixels, its design reduced to a few key animating parts (mandibles, legs, a glowing weak spot). The art trusts the player’s brain to do the work, a hallmark of great low-fi design.

Sound design, by necessity, is equally chiptune. The source material provides no specifics, but for a #LOWREZJAM entry, the audio is certainly synthesized, using 1-4 channels. Expect a looping, urgent bassline for the hoverbike, sharp digital “pew” or “blip” sounds for the gun, and a low, ominous hum for the deep hole. A simple, escalating arpeggio would likely play during the boss fight. The sound does not attempt realism; it attempts affect. It is another layer of symbolic information in a game where every byte counts.

Together, the art and sound create a world that feels simultaneously ancient (like a 1989 Game Boy title) and eerily futuristic (the “Mercury” theme). It exists in a liminal aesthetic space, much like the Nintendo 64 itself did between 2D and 3D. The atmosphere is one of lonely, sterile conflict—a war on a monochrome frontier.

Reception & Legacy: The Echo in the Void

Official critical reception for 64 Mercury is virtually non-existent in the provided sources. MobyGames lists an “n/a” Moby Score and has no critic reviews, only the entry itself and a single player review on itch.io calling it “Fun” and noting death “at the bee” (presumably the insect boss). Its commercial model is “Freeware / Free-to-play / Public Domain,” ensuring its primary audience was jam participants and curious indie hunters.

Its legacy, therefore, cannot be measured in awards or sales. It must be measured in concept and context. Within the #LOWREZJAM community, it is one of hundreds of entries, but its specific framing as a “demake” ties it to a broader trend of retro-engineering that has fascinated indie developers for a decade. It predates, but philosophically aligns with, the wave of source code decompilation and fan ports that later consumed Super Mario 64 (a topic of extensive documentation in the sources). Both projects are acts of archaeological wonder—one, 64 Mercury, imagining what a beloved style would have looked like on ancestor hardware; the other, the Super Mario 64 decompilation, preserving and dissecting the actual artifact.

Its most significant legacy is as a proof-of-concept for “jam-scale” homages. It demonstrates that you don’t need a 50-hour RPG to explore a gameplay idea or pay tribute. You need a strong mechanical core (run-and-gun + vehicle + boss) and the discipline to execute it in a microcosm. In this, it is a spiritual successor to the “shareware” era of PC gaming (episodes of Doom, Duke Nukem 3D) but with an even tighter focus. It asks: what is the smallest possible complete game loop that still feels like a full experience? Its answer: three tightly-designed, mechanically distinct 5-minute levels.

Conclusion: A Monument in Miniature

64 Mercury is not a lost classic. It was never hidden, never commercially suppressed. It is a deliberate, fleeting creation, as ephemeral as a sketch. Yet, in an industry obsessed with scale—open worlds, 100-hour campaigns, cinematic fidelity—it is a radical act. It is a game that understands that all game design is constraint design. Whether imposed by the 64 kilobyte ROM limits of the NES, the polygon budget of the Nintendo 64, or the 64×64 pixel grid of a game jam, constraint is the engine of creativity.

As a “demake” of Project Mercury, it engages in a dialogue across time. As a #LOWREZJAM entry, it engages in a dialogue about aesthetics. As a playable artifact, it offers a perfectly formed, 10-minute burst of competent, varied run-and-gun action. Its true subject is not the “Mercury” invasion, but the invasion of memory—the haunting idea that familiar genres and styles can be compressed, reconstituted, and made fresh through sheer, focused intention.

In the grand museum of gaming, 64 Mercury does not hang in the main hall beside Super Mario 64 or The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. It resides in a pristine, climate-controlled case in the annex labeled “Game Studies.” It is a primary text for understanding constraint, homage, and the indie jam’s role in preserving and reinterpreting design history. It is, in its own tiny, pixelated way, a perfect game. Its verdict is not that it is one of the “greatest of all time,” but that it is a perfectly realized artifact of a specific, potent design philosophy: that from the smallest frame, a complete world can be built, if only you have the eyes to see it and the will to build it, one 64×64 pixel at a time.