- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Legacy Software

- Developer: Legacy Software

- Genre: Adventure, Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Investigation, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Detective, Mystery

- Average Score: 40/100

Description

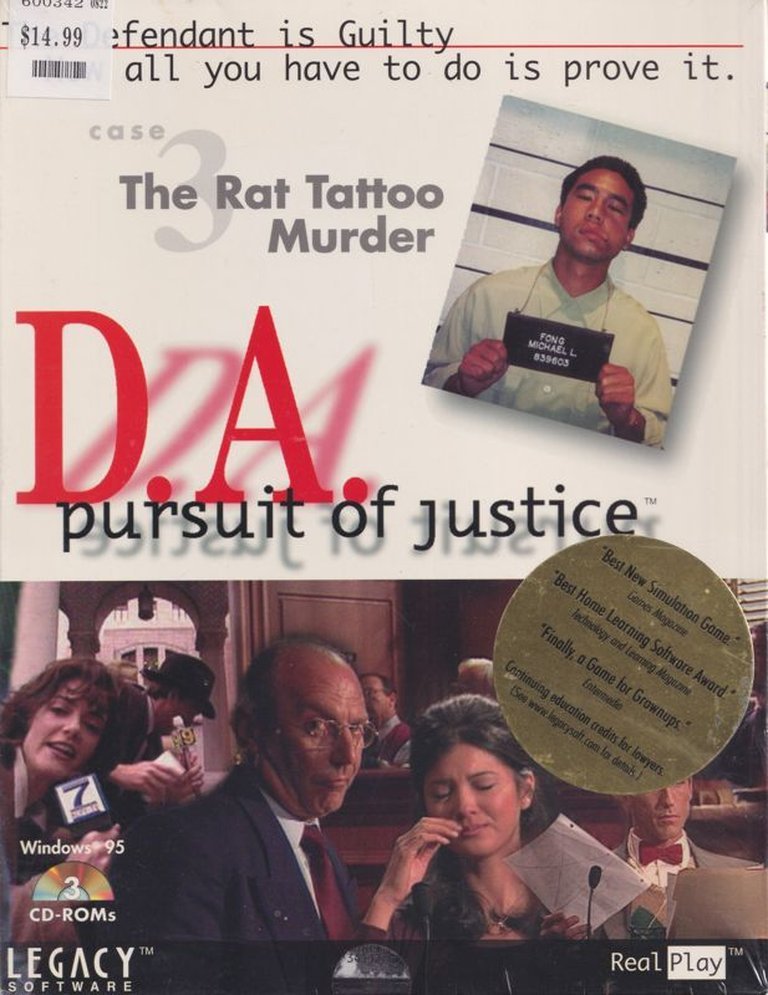

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder is a first-person adventure and simulation game where players assume the role of an Assistant District Attorney for the State of California. The game revolves around solving the murder of Tommy Wu, who was killed after a confrontation between two rival gangs at a pool hall. Players must gather evidence, analyze witness statements, and study legal case studies to determine if the crime was an accident or premeditated murder, using an on-screen notebook computer to organize their case before presenting it in court.

Mods

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (40/100): Critics Average score: 40% (based on 1 ratings)

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder: An Exhaustive Historical Analysis

In the pantheon of 1990s video games, certain titles have faded into obscurity, remembered only by niche communities or those who stumbled upon their peculiar charms in bargain bins. Others, despite their initial failure, have gained a legendary status as cautionary tales or cult classics. D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder belongs firmly to the latter category. As the third case in Legacy Software’s ambitious legal simulation series, this game stood at the precipice of a new era for PC gaming—a time when the promise of interactive narratives and “movie quality” video on CD-ROM seemed like the inevitable future of the medium. Yet, its execution and legacy tell a complex story of a genre on the cusp of transformation, one that ultimately stumbled under the weight of its own ambitions. This review will conduct a deep archaeological dig into The Rat Tattoo Murder, examining its development, dissecting its narrative and mechanics, and assessing its place in the historical continuum of legal simulations and interactive drama.

1. Introduction

The year is 1997. The PC gaming landscape is a vibrant, eclectic mix. On one front, the golden age of isometric RPGs is in full swing with titles like Baldur’s Gate on the horizon. On another, the real-time strategy boom led by Command & Conquer and StarCraft is reshaping competitive gaming. It is also the twilight of the Full Motion Video (FMV) craze that began with the success of titles like The 7th Guest and Myst. While the most innovative experiments had passed, the allure of live actors and cinematic storytelling still held significant commercial sway. It was into this dynamic environment that D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder was released, promising a taste of the gritty reality of a prosecutor’s life.

My thesis for this deep dive is that The Rat Tattoo Murder represents a fascinating and flawed microcosm of the late-90s ambitions for PC gaming. It is a product of its time, a valiant attempt at creating an authentic legal simulation that was hampered by technological constraints, a punishingly obtuse design philosophy, and a pricing model that alienated its potential audience. While it has been largely forgotten by mainstream history, its failure offers invaluable insights into the challenges of marrying simulation with narrative, and why certain genres, despite their conceptual appeal, struggle to find a sustainable audience. This analysis will argue that while The Rat Tattoo Murder falls short as a “game” in the traditional sense, it stands as a significant historical artifact, a document of an era’s dreams and limitations.

2. Development History & Context

To understand The Rat Tattoo Murder, one must first understand its creator, Legacy Software, and the specific moment in time that spawned it. Legacy Software, founded in the early 90s, was a developer obsessed with the idea of simulation and education. Their portfolio, which included titles like Emergency Room, demonstrated a clear niche: creating immersive, content-rich experiences that purported to simulate real-world professions and scenarios. This was a time before the modern ubiquity of “edutainment,” when the PC was seen as a potential gateway to new forms of learning and interactive professionalism.

The vision for the D.A. series was nothing short of audacious. The developers sought to craft a comprehensive legal simulation, a game that would not only entertain but also educate the player on the complexities of the American legal system, from evidence gathering and legal precedent to courtroom strategy. The goal was to deliver an “on-screen notebook computer” that would provide everything a District Attorney needed to build a case. This ambition was born directly from the technological promise of the CD-ROM format. With its vastly increased storage capacity compared to floppy discs, developers could now incorporate hours of video footage, extensive libraries of text, and high-fidelity audio.

However, this ambition ran headlong into the technological and budgetary constraints of the era. While “movie quality video” was the promise, the reality for most 1997 productions was often grainy, compressed MPEG-1 footage, plagued by low frame rates and a “video game cutscene” aesthetic that could be jarringly artificial. The development process for such a game was monumentally expensive, requiring not only programmers and artists but also a full cast of actors, directors, legal consultants, and scriptwriters. This cost is directly reflected in the game’s business model. As noted in historical records, the full series spanned eight CDs and cost consumers approximately a hundred dollars. This was an enormous price point for a PC game in 1997, effectively pricing it out of the impulse-buy category and placing it in the realm of a serious, high-investment purchase.

The gaming landscape at the time was also saturated with more immediately gratifying experiences. For a player seeking entertainment, a complex, text-heavy, and procedurally demanding legal simulation was a stark contrast to the action-packed excitement of Quake or the strategic depth of Age of Empires. The D.A. series was targeting a very specific, patient, and intellectually curious audience, a niche that was likely far smaller than the developers hoped. This context is crucial: The Rat Tattoo Murder was not a game made in a vacuum; it was a product of a developer’s bold vision, the technological limitations of its time, and a market that was beginning to show fatigue with the FMV genre’s more ambitious, less polished implementations.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The central narrative of The Rat Tattoo Murder is a classic, no-frills detective procedural, a choice that grounds the game’s lofty ambitions in a familiar genre framework. The plot is direct and morally ambiguous: Tommy Wu, a young man, is dead following a violent altercation between two rival gangs at a pool hall. The central question for the player, cast as an Assistant District Attorney for the State of California, is whether his death was a tragic accident or a pre-meditated murder. This setup immediately establishes the core thematic tension of the game: the pursuit of justice within a complex, often messy, legal and social reality.

The narrative is delivered through two primary channels: static text documents and live-action video cutscenes. The text documents form the backbone of the simulation. These include police reports, witness statements, coroner’s findings, legal statutes, and historical case law. Reading through these documents is where the game’s educational promise truly shines, or perhaps falters, depending on the player’s perspective. The language is deliberately formal and legalistic, forcing the player to parse dense information to extract key facts. For example, a witness statement might contain a crucial detail buried within three paragraphs of hearsay and emotional language. The “Case Constructor” briefcase, where the player must assemble the puzzle pieces, is the physical manifestation of this narrative disassembly. The player must act as a detective and a legal scholar, sifting through the noise to find the signal.

The live-action cutscenes, featuring “real actors and actresses,” serve to humanize the cold, hard facts. They depict interactions with witnesses, suspects, and legal colleagues. However, without the benefit of critical reviews of the acting quality, we can infer that the performances likely fall into the typical FMV trap: they range from serviceable to wooden, often feeling more like depositions than dramatically engaging scenes. The characters are archetypes: the grieving family member, the street-wise informant, the slick defense attorney, and the hardened police detective. Their primary function is to provide information, not to drive a character-driven story.

The underlying themes are where the game attempts to elevate itself beyond a simple puzzle box. It grapples with the nature of proof, the ethical responsibilities of a prosecutor, and the social implications of gang violence. The title itself, “The Rat Tattoo Murder,” hints at a story of betrayal and loyalty, central themes in any gang narrative. The player’s task is not simply to win, but to build a case that is ethically sound and legally unassailable. The threat of taunting from the “opposing council” in the event of failure reinforces the game’s central theme: the legal system is a battleground of wits and evidence, and a misstep has real consequences. While the narrative may be straightforward, the process of uncovering it is the game’s true narrative, a procedural story of diligence, deduction, and the meticulous construction of truth.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The gameplay of The Rat Tattoo Murder is its most defining and polarizing feature, functioning as a hybrid of adventure game puzzle-solving and simulation. The core loop is divided into two distinct phases: the investigation phase and the trial phase. This two-act structure is intended to provide a complete experience of the legal process.

The Investigation Phase:

This phase is dominated by the “point and click” interface and the game’s signature information-gathering systems. The player navigates using an on-screen map, traveling between key locations like the police station, the crime lab, and the courtroom. At the police station, the player can access a database of evidence and witness statements. Each piece of information is a node in a vast web of facts, and the player’s job is to connect them. The process involves ordering lab results, which are then delivered to the crime lab for collection, and cross-referencing legal statutes with the facts of the case to build a coherent legal argument. The central mechanic here is information management. The player must read, analyze, and categorize dozens of documents, looking for contradictions, corroborations, and crucial details that might be easy to miss. This is less about reflexes and more about patience, attention to detail, and logical reasoning. The game essentially turns the player into a legal researcher, a role that is profoundly un-gamelike by modern standards.

The “Case Constructor”:

This is the heart of the game’s puzzle element. The “Case Constructor” is a metaphorical briefcase where the player organizes the pieces of their case. Based on the source material, the player must “put all the components in the proper places” to succeed. This implies a system of drag-and-drop logic puzzles, where evidence, testimonies, and legal arguments must be correctly sequenced and categorized to form a prosecutable argument. This is where the game’s difficulty likely becomes immense. A single misplaced piece of evidence or a flawed logical chain could lead to failure. The system is innovative in its intent—it’s a literal representation of building a legal case—but its reliance on precise, non-intuitive placement is a classic example of obtuse game design from the era.

The Trial Phase:

While the source material does not detail the trial mechanics in depth, it’s implied that the organization work done in the Case Constructor directly informs the courtroom proceedings. One can surmise that the player would use the assembled case to examine witnesses, present evidence, and make legal objections, likely through a series of multiple-choice menus or timed responses. The game’s description of the goal as “to prove that a crime has been committed and that the defendant being tried did commit the crime” suggests a binary outcome: a successful conviction or a failure that results in the criminal going free and being “taunted by the opposing council.”

UI, Innovation, and Flaws:

The user interface is designed to mimic a computer desktop, with the notebook, map, and case constructor as primary applications. This is an early example of diegetic UI, attempting to immerse the player in the role of a professional using their tools. The innovation is in the sheer volume of data presented to the player. However, the flaw is in the accessibility of that data. Navigating a sea of text documents with a point-and-click mouse interface from 1997 could be a tedious and frustrating experience. The game’s challenge comes not from clever puzzles, but from its sheer density and the lack of hand-holding. This is a system that demands significant intellectual investment from the player, a high bar that likely contributed to its poor commercial and critical reception.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound

Given that The Rat Tattoo Murder is a legal simulation set in a contemporary American city, its “world-building” is less about fantastical lore and more about the meticulous recreation of a specific, gritty milieu: the urban underbelly of California. The setting is a character in itself—a world of pool halls, gang violence, police precincts, and sterile courtrooms. The game’s art direction, as conveyed through its video assets and static backgrounds, aims for a sense of realism. The pool hall, for instance, is likely rendered in the visually unglamorous but authentic style of its time, complete with smoke-filled air and the clash of cue sticks. The police station would be a world of desks, filing cabinets, and fluorescent lighting, a stark contrast to the dark, dramatic lighting one might find in a L.A. Noire or a Max Payne.

The visual presentation is, of course, dominated by its Full Motion Video (FMV) components. The “movie quality video” promised in the marketing was the game’s primary selling point, but from a historical perspective, it’s its greatest technical liability. The video quality would have been constrained by the limitations of the CD-ROM format, resulting in a low-resolution, often pixelated, and artifact-ridden image. The camera work is likely static, with actors performing directly to the lens in a “talking head” style, which can break immersion. The static backgrounds, meanwhile, would have served as a stage for these video performances, creating a composite aesthetic that was common for the era but rarely seamless. The overall visual impact is one of a time capsule—a fascinating look at how developers tried to inject cinematic realism into games before the technology was truly mature.

The sound design would have been a crucial component in establishing the game’s atmosphere. The description of an “original musical sound track” suggests an attempt to create a dynamic score, likely swelling during moments of drama and tension. Sound effects, such as the din of the pool hall or the sterile quiet of a lab, would have been vital in grounding the player in the environments. While the quality of the acting in the FMV is unknown, the sound mixing would have been key to making the experience believable. The absence of a dynamic action score highlights the game’s deliberate pacing; this is a game of atmosphere and tension, not of bombastic set pieces. The art and sound, taken together, work to create a world that is intended to feel real and serious, even if the technological execution of that vision has not aged gracefully.

6. Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in April 1997, D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder received a critical drubbing, a fact cemented by its abysmal score on MobyGames based on a single review from Computer Gaming World. The review, earning a paltry 40% (2 out of 5 stars), is scathing in its dismissal. The reviewer’s advice is unequivocal: “Instead, pick up the much superior IN THE 1ST DEGREE at discount. Then, if you’re really serious, save the rest of your money for the tuition down-payment to Georgetown.” This is a devastating critique, not just of the game’s quality, but of its value proposition. It positions the game as an overpriced, underwhelming experience when compared to a competitor and, more damningly, to the real-world cost of actual legal education.

This critical reception reflects the game’s commercial challenges. The hundred-dollar price point was a significant barrier, and the review suggests that even consumers willing to pay a premium for a niche product felt sorely let down. The gameplay was likely perceived as tedious and unrewarding, a simulation without the fun, and the FMV, a key selling point, was probably seen as low-quality and unconvincing by 1997 standards. The game was simply out of step with the market.

However, to judge the game only by its launch reception is to miss its fascinating legacy. The Rat Tattoo Murder represents a historical dead-end in game design, a noble attempt at a “serious game” that failed commercially and critically but left behind an important lesson. Its legacy is one of cautionary tale for developers. It demonstrates the immense difficulty of creating a compelling “simulation” that is also an entertaining “game.” The gulf between the tedious reality of legal research and the engaging mechanics of interactive entertainment proved too wide for Legacy Software to bridge.

Furthermore, the game’s release history tells a story of adaptation and market correction. Initially sold as a separate, expensive three-CD case, it was later bundled with its predecessors, and in 2001 re-released as a stand-alone product under the simpler title Pursuit of Justice. This evolution shows the publisher struggling to find a viable business model for the content, eventually conceding to a lower price point and a more streamlined identity. Today, The Rat Tattoo Murder exists as a piece of gaming history, a fascinating artifact from an era when the line between game, simulation, and education was still being aggressively and often clumsily redrawn. It is remembered by enthusiasts of obscure PC titles and serves as a reference point for discussions about the evolution of narrative and simulation in video games.

7. Conclusion

After this exhaustive analysis, the final verdict on D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder must be nuanced. As a piece of entertainment in 2024, it is almost certainly a failure. Its gameplay is archaic, its presentation is dated, and its pacing is anathema to modern gaming sensibilities. The punishing difficulty and obtuse mechanics would likely alienate all but the most masochistic of history buffs. Its critical reception upon release was justified; it was an overpriced, underwhelming product that failed to deliver on its ambitious promises in a compelling way.

Yet, to dismiss it solely as a “bad game” is to do a disservice to its historical significance. The Rat Tattoo Murder is a perfect encapsulation of a specific moment in the evolution of video games. It is a product of the CD-ROM boom, a time when developers believed they could use new technology to create entirely new genres of interactive experiences. It represents the zenith of the legal simulation subgenre’s first wave, a title that pushed the boundaries of what a game could be, even if it did so without success.

In the grand pantheon of video game history, D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Rat Tattoo Murder holds a unique place. It is not Citizen Kane, nor is it E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. It is something more specific: it is a fascinating, flawed, and forgotten artifact, a digital fossil that tells us more about the dreams and delusions of the late 90s PC gaming market than any number of successful titles ever could. It stands as a testament to the difficulty of translating complex, real-world professions into engaging gameplay, and as a reminder that for every giant leap forward the medium takes, there are numerous, noble stumbles into the void. Its place is secure, not as a classic to be celebrated, but as a crucial, if cautionary, chapter in the ongoing story of interactive entertainment.