- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, PAN Vision AB, troll.ru

- Developer: Artplant AS

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Puzzle, Sword fighting

- Setting: Pirate, Sea

Description

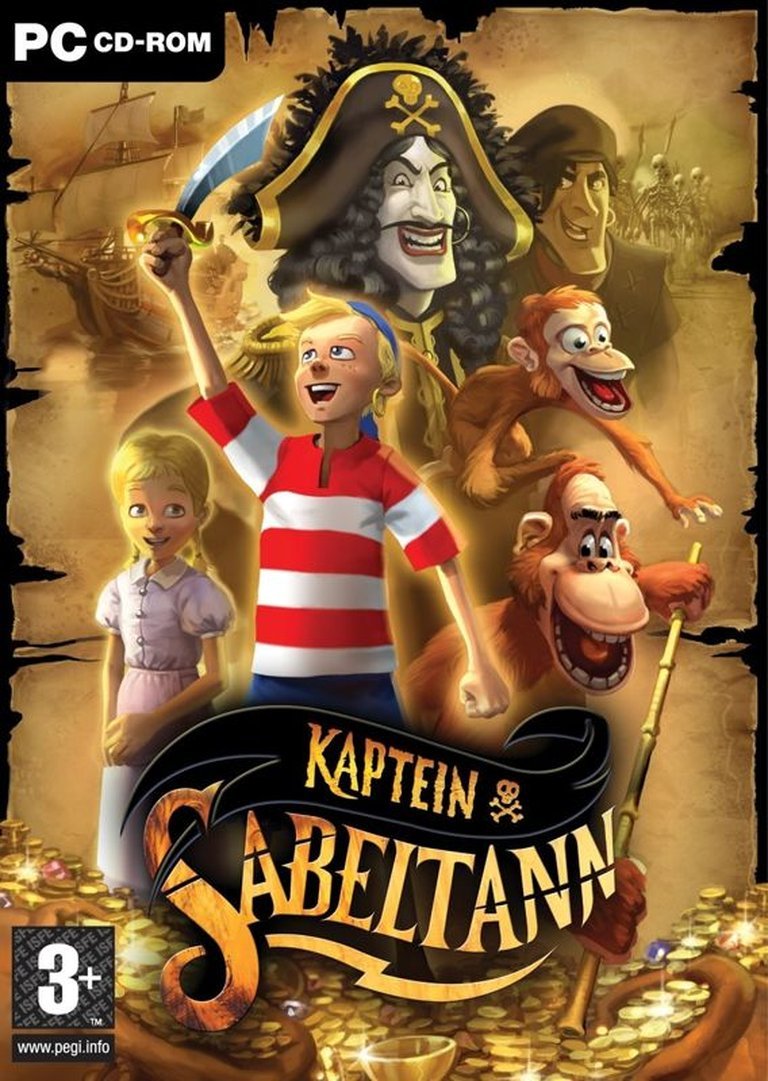

Kaptein Sabeltann is a pirate-themed action-adventure game based on the Norwegian fictional character Captain Sabertooth, where players control young Spinky aboard the ship ‘The Black Lady’ to locate Red Ruby’s lost treasure. The game features 3D environments with behind-the-shoulder perspective gameplay, combining platform jumping, sword combat against pirates and skeletons, puzzle-solving, and cannon battles between levels. Players collect gold to purchase equipment like swords, lanterns, and shovels while avoiding unbeatable enemies like crabs and scaring away monkeys, with child-friendly mechanics that avoid permanent death by knocking out foes.

Gameplay Videos

Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com : was an above-average platform title in its time.

archive.org : Named the best Nordic children’s game by the Nordic Game Awards.

Kaptein Sabeltann: Review

Introduction

To truly understand a video game, one must first look beyond the code and pixels, to the cultural soil from which it sprang. For a Norwegian child growing up in the early 2000s, summer was not just a season of sun and freedom, but a pilgrimage to Kristiansand Dyrepark to witness the live theatrical adventures of Kaptein Sabeltann. This larger-than-life pirate, created by singer and actor Terje Formoe, was a national phenomenon, a symbol of swashbuckling adventure, catchy sea shanties, and the simple triumph of good over evil. The 2004 PC game, Kaptein Sabeltann, was not merely a licensed product; it was an extension of this beloved universe, a digital key that could unlock the magic of the amfiteater for the solitary player at home.

This review seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of Kaptein Sabeltann, placing it within its specific historical and cultural context. We will deconstruct its development history, narrative structure, and gameplay mechanics, and examine how its world-building, art, and sound design coalesced to create a quintessentially Norwegian gaming experience. Ultimately, while its technical prowess may not have challenged the titans of the industry, the game’s true legacy lies in its perfect execution as a children’s adventure and a faithful digital ambassador for one of Norway’s most enduring cultural exports.

Development History & Context

The story of Kaptein Sabeltann the game is inextricably linked to its creator and the studio tasked with bringing the pirate to life. The game emerged directly from the immense popularity of the 2003 animated film Kaptein Sabeltann, itself an adaptation of Formoe’s decades-long success in theatre. This film, with its accessible story, memorable characters voiced by a cast including Terje Formoe himself, and a budget of 41.5 million NOK, served as the primary blueprint for the game’s narrative, setting, and even its audio-visual assets. As confirmed by the game’s credits and Wikipedia entry, the player controls Pinky, and the game uses film clips from the 2003 movie to advance the story between chapters, a common practice for licensed games of the era designed to leverage the existing media’s popularity.

The development of this ambitious project was entrusted to Artplant AS, a Norwegian studio founded in 1996. Artplant was already an established name in the burgeoning Norwegian games industry, known for creating digital experiences for a wide range of clients. Given the tight timeline and the need to produce a game based on a major film, Artplant’s experience was crucial. The project was led by Tomas Sandnes and produced by Christer Olsson for PAN Vision, a prominent Nordic distributor. A key technical detail, noted in several sources, is the game’s use of QuickTime for its cutscenes, a requirement that has since become a point of nostalgia and a minor hurdle for modern players attempting to run the game. This choice highlights the technological constraints and standard practices of the mid-2000s, where integrating pre-rendered video was a common way to deliver high-fidelity cinematic experiences on a budget.

The gaming landscape in 2004 was dominated by the sixth console generation, with the PlayStation 2, Xbox, and GameCube reigning supreme. In this arena of high-definition textures and sprawling open worlds, a simple 3D action-adventure game for PC, aimed at a young audience, might seem like a niche release. However, the PC market was still a vibrant space for family-friendly games and licensed titles. Kaptein Sabeltann occupied a unique position: it was a locally developed and published title, tapping into a massive, built-in fanbase that cared more for the faithful recreation of Sabeltann’s world than for cutting-edge graphics or complex gameplay. Its development was not an attempt to compete with global AAA blockbusters, but rather a focused effort to create a high-quality digital adventure for a specific, passionate audience, a mission for which it was ultimately well-suited.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Kaptein Sabeltann is a masterclass in accessible, goal-driven storytelling, perfectly calibrated for a young audience. The plot is a classic quest, distilled to its most essential elements. The player assumes the role of Pinky, the young, ambitious cabin boy aboard the fearsome pirate ship, Den sorte dame (The Black Lady). Pinky’s dream is simple and universal: to become a real pirate. The central goal is to help his captain, the legendary Kaptein Sabeltann, locate the lost treasure of the ghostly pirate, Grusomme Gabriel (Cruel Gabriel). This objective is broken down into a series of tangible, repeatable tasks: find the scattered pieces of a treasure map. Each recovered piece serves as a narrative and structural stepping stone, granting access to new levels and new adventures. This progression is both satisfying and easy to grasp, providing a clear sense of purpose throughout the game.

The narrative structure is supported by a cast of instantly recognizable characters from the Sabeltann universe. The protagonist, Pinky, is the player’s avatar, an underdog whose journey from cabin boy to hero is the emotional core of the experience. His motivations—dreams of glory and the desire to prove his worth—are simple yet potent. Kaptein Sabeltann himself is the archetypal pirate captain: fearsome to his enemies but with a code of honor and a hint of paternal pride towards his crew. The game’s use of the original film’s voice cast, including Terje Formoe as Sabeltann and Ole Alfsen as Pinky, lends an incredible layer of authenticity. Hearing the iconic voices, not dubbed but recorded in their native Norwegian, grounds the entire experience in the familiar warmth of the theatrical and filmic productions, making the digital adventure feel like a legitimate extension of the canon.

Beyond the surface-level pirate adventure, the game explores several subtle but important themes. The most prominent is the theme of growth and self-discovery. By helping Sabeltann, Pinky is not just finding treasure; he is earning his place in the crew and inching closer to his dream. This reinforces the idea that one’s worth is proven through action and courage. Furthermore, the game champions resourcefulness. Pinky cannot simply fight his way through every challenge. He must explore, interact, think, and spend his hard-earned gold on essential equipment like a shovel, a lantern, and a sword. This teaches a fundamental problem-solving lesson: the right tool is as important as a strong will. The absence of death, where defeated enemies are merely “knocked out,” reinforces the game’s child-friendly ethos, framing conflict as an obstacle to be overcome rather than a source of permanent failure. It’s a world of consequence, but not of cruelty.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Kaptein Sabeltann is a 3D action-adventure game built on a foundation of three core mechanics: platforming, puzzle-solving, and simple combat. The player navigates Pinky through vibrant, linear 3D worlds from a fixed behind-the-shoulder perspective, a viewpoint that keeps the character visible and the environment clearly in focus. Interaction with the world is elegantly streamlined for a younger audience, centered around a single, primary action: the space bar. At specific hotspots, pressing space triggers context-sensitive actions, whether it’s jumping to a ledge, pushing a crate, initiating a conversation, or performing a sword strike. This design choice minimizes controller complexity, allowing children to focus on exploration and discovery rather than mastering a complex control scheme.

The gameplay loop is a compelling cycle of acquisition and utility. As Pinky explores, he collects gold coins, a tangible representation of his success. This currency is then spent in shops at key locations, creating a clear progression system. The need to purchase a sword is the first major hurdle, immediately opening up the combat aspect of the game. This is followed by the essential lantern, which becomes a gateway to previously inaccessible dark areas, and the shovel, which unlocks new paths by allowing Pinky to dig for hidden treasure or remove obstacles. This equipment-based progression is a classic and effective game design trope, making each new purchase feel like a significant milestone and a key to unlocking the next part of the adventure.

Combat is intentionally simple, reflecting the game’s PEGI 3 rating. Fights are one-on-one sword duels against pirates and skeletons, initiated by getting close to an enemy. The player presses the spacebar to lash out, and the enemy does the same. The challenge lies in timing and positioning rather than complex combos. Some enemies, like monkeys, cannot be fought directly and must be scared away, while others, like crabs, are purely avoidable. This variety keeps encounters fresh and encourages different player strategies. Each level culminates in a boss fight, which serves as a more significant challenge. These bosses require the player to identify and exploit a weakness, adding a rudimentary layer of puzzle-solving to the combat and providing a satisfying sense of accomplishment at the end of each stage.

A unique and memorable mechanic is the ship navigation between levels. The player gets to steer Den sorte dame with the mouse, providing a brief respite from on-foot platforming. This interlude is not without danger, as enemy pirate ships can attack, triggering a first-person cannon mini-game. Here, Pinky takes control of the ship’s cannon, and the player must aim and fire to destroy the three cannons on the opposing vessel before their own ship is sunk. This segment breaks up the pace, offers a different style of gameplay, and reinforces the pirate theme, making the journey between islands as much a part of the adventure as the exploration itself.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Kaptein Sabeltann is its most triumphant achievement, a digital recreation of a universe that already felt real and beloved to an entire generation of Norwegians. The game faithfully translates the key locations from the films and plays: the bustling pirate haven of Abra Havn, the mysterious jungles of Kjuttaviga, and the treacherous volcanic island of Apön (Monkey Island). These environments are more than just backdrops; they are characters in their own right. The art direction, led by artists Chester Lawrence Laquian, Joachim Barrum, and Mikael Noguchi, captures the vibrant, slightly cartoonish aesthetic of the source material. The textures are simple but effective, with bright, saturated colors that pop against the deep blues of the sea and greens of the jungle. The level design is linear and focused, guiding the player with clear objectives, but each area is filled with nooks and crannies to reward curiosity, ensuring that the world feels expansive and alive within the constraints of its design.

One of the most charming aspects of the game’s presentation is the clever use of references. As noted on the MobyGames trivia page, the Swedish version of the game features an island named “Apön,” which is not just a name but a direct homage to Monkey Island. The layout, complete with a central volcano surrounded by jungle, mirrors the iconic design of LucasArts’ classic adventure series. This is a knowing wink to older players and fans of the genre, adding a layer of depth for parents playing alongside their children and demonstrating that the developers were true connoisseurs of adventure game history.

The audio design is where the game truly connects with its audience on a deeply emotional level. The most critical element is the authentic vocal performance. The game features the original voice cast from the 2003 film, including Terje Formoe as the booming, charismatic Kaptein Sabeltann. Hearing these familiar voices deliver their iconic lines in Norwegian provides an unparalleled sense of immersion and authenticity. This is not a generic dubbed product; it is the real Sabeltann. The sound effects are equally evocative, from the clink of a gold coin to the sharp thwack of a sword fight, all designed to complement the pirate theme without being overwhelming.

Furthermore, the game integrates the music of Terje Formoe. While the game description does not specify if the full orchestral score from the film is used, it is highly likely that tracks or motifs from the plays are featured. The combination of familiar voices, thematic sound design, and the potential for musical cues creates a powerful audio-visual package that feels less like a video game and more like an interactive episode of the Kaptein Sabeltann saga. It successfully bridges the gap between the passive experience of watching a film and the active participation of playing a game, making the player feel like an active part of Pinky’s adventure.

Reception & Legacy

Kaptein Sabeltann was released into a market with no direct competition for its specific niche. As a licensed children’s game based on a major Norwegian cultural property, its commercial success was nearly guaranteed. The MobyGames entry reports that by November 2007, the game had sold over 20,000 copies in Norway alone—a significant number for a PC title in a country of just over 5 million people, especially considering its target audience. This solidified its status as a commercial hit and a staple in many Norwegian households. While contemporary critical reviews are sparse—Metacritic lists no critic scores, and MobyGames shows only a single user rating of 3.3/5—the game did not need the validation of the international gaming press. Its reception was measured in sales, player satisfaction within its target demographic, and its role as a cherished piece of childhood memory.

The game’s legacy is not one of industry innovation or technical influence. It did not spawn a new genre or redefine game design. Instead, its legacy is deeply cultural. For the children of Norway, it was a gateway to the Sabeltann universe, a way to carry the summer’s adventure into the winter, a way to live out the pirate fantasy in their own homes. It preserved the magic of the character in an interactive format and likely served as an introduction to video games for a generation of Norwegian kids. Its success directly led to the development of a sequel, Kaptein Sabeltann: Grusomme Gabriels forbannelse, released in 2007. This sequel, which introduced new characters from the theatrical universe and was nominated for “Årets norskspråklige spill” (Norwegian Game of the Year), built upon the foundation laid by its predecessor, further cementing the franchise’s presence in interactive media.

The game also holds a place as a document of a specific time in Norwegian digital culture. Today, it survives as a piece of abandonware, with communities like MyAbandonware and the Internet Archive preserving it for posterity. The technical notes left by these preservationists—advice on using compatibility modes or dgVoodoo wrappers—are a testament to its role as a nostalgic artifact. It represents a time when licensed games could be simple, charming, and culturally specific, finding their success not by appealing to the global market, but by faithfully serving the community that loved their source material.

Conclusion

After a thorough examination of its creation, mechanics, and cultural impact, Kaptein Sabeltann reveals itself to be far more than just a rudimentary licensed game. While it may lack the technical polish and design complexity of its contemporaries in the broader gaming world, it succeeds perfectly on its own terms. It is a lovingly crafted, faithful, and engaging piece of interactive entertainment designed for a specific audience and purpose.

The game’s strengths lie in its seamless integration with the beloved Kaptein Sabeltann universe. Through its use of the original voice cast, familiar settings, and a narrative that honors the spirit of the theatrical productions, it creates an authentic and emotionally resonant experience. Its gameplay, though simple, is well-designed for its target demographic, providing a structured and satisfying adventure that encourages exploration, problem-solving, and a sense of accomplishment. The blend of platforming, light combat, and ship navigation creates a varied pace that keeps young players engaged.

Ultimately, Kaptein Sabeltann’s place in video game history is as a significant cultural artifact within Norway, a country with a smaller but passionate game development scene. It stands as a prime example of how a licensed property can be successfully adapted into a video game not by chasing industry trends, but by understanding and celebrating the unique qualities of the source material. It is a digital time capsule, a testament to the power of a shared cultural dream, and a fun, charming adventure that, for its intended audience, was nothing short of perfect. Its legacy is not written in sales charts or critic scores, but in the fond memories of a generation of Norwegian children who, for a few hours, got to be pirates on the high seas.