- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: American Laser Games, Inc.

- Developer: Her Interactive, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

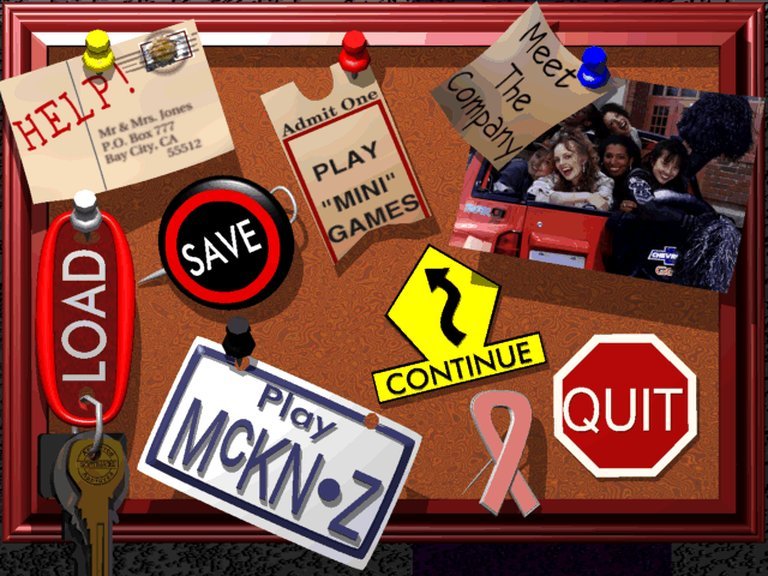

- Gameplay: Concentration, Live action cut-scenes, Mini-games, Picture puzzle, Shooting accuracy, Tetris

- Setting: High school, Teen life

- Average Score: 58/100

Description

In ‘McKenzie & Co.’, a pioneering adventure game developed by Her Interactive, players assume the role of a teenage co-ed navigating her junior year at Madison High, living an interactive, decision-driven high school life. The game revolves around typical teen experiences—attending classes, socializing with six close friends and 20 other characters, dating prospective boyfriends, shopping for clothes, doing homework, and working after-school jobs—all portrayed through live-action video clips and first-person perspective. Players choose from two main characters and engage in branching conversations by selecting dialogue responses, while completing mini-games like Concentration, Tetris, shooting challenges, and picture puzzles woven into the narrative. Released in 1995 for Windows and Macintosh across six CD-ROMs, the game features real actors, a bonus music CD, and an optional internet access package, with special physical extras like makeup samples and a pink ribbon supporting breast cancer awareness, reflecting its unique and earnest approach to portraying teen life.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy McKenzie & Co.

PC

McKenzie & Co. Free Download

Patches & Updates

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (69/100): This adventure game, the first ever released by Her Interactive, lets you take on the life of a teenage co-ed in her junior year at Madison High.

sockscap64.com (48/100): This Game has no review yet, please come back later…

McKenzie & Co.: Review

In the ever-evolving tapestry of video game history, few titles have stood at the intersection of passion, controversy, innovation, and socio-cultural significance with such bold, often unfiltered candor as McKenzie & Co. (1995). This FMV “social adventure”—released by Her Interactive, then an obscure division of American Laser Games, long known for live-action shoot-’em-ups like Mad Dog McCree—was not just another CD-ROM curio. It was a daring, audacious, and deeply emblematic entry into the nascent conversation about gender, representation, and the redefinition of what a “girly” game could be in the ’90s.

At a time when the gaming landscape was dominated by teenage boys, violent shooters, and male-coded narratives, McKenzie & Co. emerged like a pastel-colored earthquake: a full-motion video (FMV) dating sim hybrid with 184 credited team members, filmed on real sets with real actors, aimed squarely at girls ages 10–16. It asked players to navigate the labyrinth of high school social hierarchies, the thrill of prom, the stress of finals, and yes, the agony and ecstasy of trying to get asked to the biggest night of junior year. Its very existence challenged the industry’s assumption that girls did not play—or would not want to play—video games at all.

Yet its legacy has been far from simple. Praised by some as a pioneering act of inclusivity, it was dismissed by others as a cliché-ridden, stereotype-laden joke. Critics called its objective “dubious.” Salons declared it “much-reviled.” Scholars later analyzed it through lenses of feminism, consumerism, and performative femininity. Yet sales proved something different: over 80,000 copies sold, a blockbuster in its niche, proving that when a market is ignored, the first entry to fill the void can be wildly successful—no matter how flawed.

This review is an exhaustive autopsy of McKenzie & Co., not merely as a piece of game software, but as a cultural artifact, a feminist experiment, a product of its time, and a forerunner of a genre that would evolve into modern narrative-driven games for underrepresented audiences. We will dissect its development, narrative, gameplay systems, technical audacity, reception, and enduring place in the history of games. We argue that McKenzie & Co. is not a great game by traditional metrics—its mechanics are simplistic, its FMV quality inconsistent, its choices often illusory—but it is an essential game by historical, social, and ideological ones. Its significance lies not in how well it played, but in how boldly it aimed to represent a group long told they didn’t belong in the gaming world.

In short: McKenzie & Co. may not have been fun in the way a Shooter or RPG was, but it was important—perhaps the most important girl-focused game of the 1990s, and a timeless case study in the power, peril, and promise of gaming as a tool of cultural representation.

Development History & Context

Origins: A Company Born from a Mother’s Frustration

In 1993, as the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo battled it out for console supremacy and CD-ROM technology began to promise the future of interactive media, a quiet revolution was brewing in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Patricia Flanigan, Vice President of Marketing at American Laser Games (ALG)—best known for their live-action arcade shooters like Mad Dog McCree, Crime Patrol, and Space Pirates—found herself frustrated. Her daughters played games, but there was nothing for them. Nothing like them. Nothing that allowed them to see themselves in the role of the protagonist.

Lazy logic from publishers told Flanigan they rejected any “girl game” proposal: “There’s no market,” they said. “Girls don’t buy games.” Undeterred, Flanigan took matters into her own hands. In 1994, she founded Her Interactive, then called “Games for Her.” The name was a provocation as much as a brand: For Her. A declaration that video games could—and should—exist beyond the male gaze.

The Research: A Two-Year, 2,000-Interview Groundwork

What set McKenzie & Co. apart from mere marketing gimmicks was its unprecedented research phase. Flanigan partnered with the Albuquerque Independent School District, distributing surveys, conducting interviews, and holding play study groups—over 2,000 girls aged 9–15 were consulted. This wasn’t tokenism. This was genuine ethnographic research, a rare feat in the ’90s, where market research often meant focus groups or guesswork.

From these interactions, her team distilled a set of core desires:

– Want to shop (but not be shamed for it)

– Want to date (but not be reduced to virgins or sluts)

– Want to be smart (juggle school, jobs, friends)

– Want to solve problems (not just run and shoot)

Flanigan later described the game as “an exciting depiction of real-life moral and social dilemmas”—a phrase rarely associated with FMV games, which were mostly pulp fiction or arcade ports.

Technology & Constraints: The FMV Frontier

By 1995, CD-ROM was maturing. The 486 processor, Sound Blaster-compatible audio, and double-speed CD drives were becoming standard. But FMV games were still technological minefields. Video had to be compressed, streams had to be buffered, and disc swapping was a constant headache. ALG’s engineers, led by Steve Frank, had experience with FMV from their arcade days, but PC integration was new. They used Macromedia Shockwave Director 4.0.1, a cutting-edge tool for CD-ROM interactivity, to build the framework.

The game was built around video backdrops—short clips (typically 5–15 seconds) triggered by player choices. But the real innovation was branching video. ALG had already mastered this in their shooters, where a wrong robbery choice led to getting shot. McKenzie & Co. repurposed that system: wrong social choice = grounded from the prom = game over. The same engine, repurposed for teenage social drama.

But the constraints were brutal:

– 6 CDs total: 1 for the core game, 4 dedicated to the four boyfriends (Brett, Steven, Derek, Brandon), and 1 bonus music CD.

– Frequent disc swaps: Up to 4–5 per session. (As SuperKids noted: “The younger end… are very forgiving about the inherent frustrations of disk swapping.”)

– Hardware limitations: From 8 MB RAM minimum to Pentium to run smoothly, with VESA-compatible graphics cards required for full visuals.

The Cultural Landscape: 1995 Was a Year of Contradictions

In 1995, the U.S. was buzzing with 90210, Clueless, Saved by the Bell, and The Babysitters’ Club. Teen girls were a growing consumer market, but no major publisher made a video game for them. The closest thing was Barbie Fashion Designer (1996), but that came later.

Her Interactive, backed by ALG’s film-production infrastructure, circumvented this by using real actors, real sets, and real lighting. This was a gamble: live-action FMV was expensive, and the competing trend in ’95 was 3D graphics (Tomb Raider premiered that year). McKenzie & Co. went analog in a digital age.

The game was also bundled with actual makeup (a “Look on the Bright Side” booklet), promotional giveaways, and tie-in coupons—blurring the line between game, product placement, and lifestyle brand. The box even included a pink ribbon for breast cancer awareness, a rare corporate social responsibility initiative at the time.

The Vision: “Social Adventure” Over “Dating Sim”

Crucially, Her Interactive refused to market the game as a “dating sim”—a term associated with Japanese otome games, often seen as niche or risqué. Instead, they called it a “social adventure”, a framing that emphasized choice, consequence, and agency. As Flanigan explained, the goal wasn’t just romance—it was navigating a complex, multi-threaded life as a high school junior.

The result was a hybrid genre: part visual novel, part life simulation, part mini-game collection, wrapped in FMV.

In many ways, it was ahead of its time—a proto-life-sim with narrative consequences, resembling Life is Strange or Persona 4 in spirit, if not execution.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Core Plot: The Prom as Metaphor

At its heart, McKenzie & Co. is a goal-driven micro-epic of adolescence: Get asked to the Junior Prom by your crush. This deceptively simple narrative conceit functions as a metaphor for social validation, self-worth, and the pressure to perform—forces that echo far beyond high school.

The player chooses between two protagonists:

– Kim Nelson, “gymnast/cheerleader”—athletic, popular, outgoing, drawn to Brett (the “cowboy” farm boy) or Steven (the preppy, soap-opera-star).

– Carly, “actress”—artistic, drama-focused, choosing between Derrick (the studious jock) and Brandon (the mysterious rebel).

The inciting incident is a sleepover in the protagonist’s bedroom, where all six members of “McKenzie & Co.” (the friend group) flip through a yearbook, reminisce, and challenge the player to pick a date. This framing is critical: the game begins not with failure or isolation, but with community, friendship, and support. The player is not alone—even in a solo game, she’s surrounded by girlfriends.

The Friend Group: A Nuanced, Diverse Ensemble

The six friends are exaggerated but not caricatures:

– Elizabeth: “Obsessed with shopping and fashion”—but not airheaded; her narrative includes saving money, comparing prices, and budgeting for prom tickets.

– Sam: Carly’s best friend, dating Bryan—shows heterosexual pairings without jealousy or drama.

– Bryan: The best guy friend—comic relief, confidant, babysitter partner.

– McKee, Trish, and others: Less developed, but serve as comic or dramatic foils.

Their relationships are non-toxic. No backstabbing. No catfights. Even when Elizabeth gossips, it’s for laughs, not malice. This is remarkable for a ’90s teen drama—aversion to the “mean girl” trope that would later dominate teen media.

Social Dilemmas: Not Just “Will He Ask?”

The game’s true depth lies in its “moral and social dilemmas”, as Flanigan described. These are not combat quests, but social navigation challenges:

- Should you skip class to hang out with him? (Risks being grounded, game over.)

- Do you tell your friend her crush likes another girl?

- Do you intervene when a teacher yells at a classmate?

- Do you flirt with multiple guys, or stay loyal to your choice?

These choices are processed through multiple-choice dialogue trees and live response video clips. The FMV format shines here: when Kim nervously smiles at Steven, or Carly stammers during their first date, the human performance sells the emotional stakes—something text or sprites couldn’t achieve in 1995.

Repetition & Illusion of Choice

Yet, a major criticism is that many paths converge. Multiple actions lead to the same video clip. Some choices have no visible consequence. This is a byproduct of FMV’s limitations: filming every permutation is economically and logistically impossible.

For example:

– Asking for a date too soon might lead to rejection.

– But asking three times in a row? Same “no thanks” clip.

– Buy a dress, don’t buy a dress—same prom photos.

This “illusion of choice” undermines the game’s ambition to be a social simulator. As Electric Playground acidly noted:

“It’s like an episode of 90210 without the sex, drugs, or malicious behaviour… but also without any sense of progression.”

Themes: Empowerment, Stereotypes, and the ‘Feminist’ Contradiction

Here lies the game’s central irony. Her Interactive claimed feminist motivations: “help lead girls down the path of computers and technology.” The company wanted girls to see themselves as problem solvers, decision-makers, and tech-savvy.

Yet the gameplay reinforces traditional gender roles:

– The goal is romantic validation (prom date, not valedictorian or MVP)

– The mechanics revolve around appearance: what you wear, what makeup you apply, how you style your hair

– The simulation includes no STEM content, no political engagement, no career paths beyond part-time jobs

The 5 teachers are all played by the same male actor—a cost-cutting move that robs academic life of diversity. The male love interests are archetypal: cowboy, jock, rebel, preppy—none are artists, nerds, or complex individuals.

As Salon (1999) snarked: “Exudes the depth of a puddle.” The Chicago Tribune called the prom objective “rather dubious.”

Yet—this was the point. Her Interactive didn’t want to make a subversive, anti-cliché game. They wanted to meet girls where they were, not shock them. They knew their audience consumed Sweet Valley High books, Brat Pack movies, and YM magazines. McKenzie & Co. mirrored their world, then draped it in interactivity.

In that sense, it’s not a feminist game, but a materialist analysis of teen girlhood: here are your choices. Here’s the social ecosystem. Navigate it.

In hindsight, it resembles a soft-core anthropological simulation more than a self-esteem booster.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Life as a Feedback Cycle

The daily gameplay loop is the game’s beating heart:

-

Home Management: In your bedroom, you:

- Change outfits (stored in a digital closet)

- Apply makeup (varied intensities)

- Read magazines (e.g., Seventeen)

- Check your diary

- Listen to voicemail

- Call friends or love interests

- Study for exams (text-based mini-games)

-

Outdoor Navigation: Use a map system to travel to 16 locations across Bay City:

- Home (sleepover, babysitting)

- School (mandatory attendance)

- Work (Kim at Sam & Libby’s, Carly at movie theater)

- Mall (Elsa Ross, Oshman’s, etc.)

- Arcade (Howie Hooper’s, mini-games)

- Drive-in, community center, hospital, etc.

-

Social Encounters: At each location, live-action clips play. You choose from 1–3 responses. Outcomes branch.

-

Goal Progression: Completing tasks (work, school, dates) accumulates “moral capital” needed for the prom ask.

-

Mini-Game Integration: Games are embedded as diegetic puzzles.

- Tetris variation: Job assignment at the arcade.

- Concentration: Study for final exams.

- Picture puzzle: Decorate the prom poster.

- Shooting accuracy: Dart game at a mini-golf date.

This loop is genuinely immersive—a 1995 version of The Sims’ life flow. As Coming Soon Magazine wrote in 1996:

“Your goal will be to pass your final exams, graduate, and have a charming young man ask you to the Junior Prom… When you pull it off, it’s a genuine rush.”

Character Progression & Customization

- Outfit System: Try on clothes, mirror reactions, buy with earnings.

- Makeup Cabinet: Multiple shades and styles.

- Voicemail Tree: Real-time calling with time-of-day logic.

- Dialogue Choices: Not skill-based, but social intelligence-based (timing, tone, reciprocity).

UI & Interface: Clunky but Contextual

- Mouse-driven interface: No keyboard combat—a forward-thinking design.

- First-person perspective: Reinforces player identity as Kim/Carly.

- HUD minimal: Screens show location, inventory, clock.

- FMV transitions: Smooth for the era, but disc swaps break immersion.

Flaws & Limitations

- Illusory Progression: Many choices lead to the same video path.

- Punitive Failure: Miss class → grounded → game over. Harsh for a casual title.

- Disc Swapping: A massive UX flaw. Frequent.

- Linear Coupling: Once you choose a guy, the other love interests fade.

- No Scoring System: No economy beyond clothing.

Yet—for a target demographic, these flaws mattered less. As High Score (1996) noted:

“Det enda jobbiga är det eviga bytandet av CD-skivor” (The only annoyance is the constant disc swapping).

For a 10-year-old girl, a 5-minute cutscene of her date driving up in a convertible cheered by her mom? That was pure joy.

The game succeeded not by the standards of Quake or Final Fantasy, but by the standards of a Teen Magazine cover: fantasy, control, and wish fulfillment.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting: Bay City, a 90s Supermall of Suburbia

Bay City is a sprawling, mall-first utopia—a pastel-hued throwback to the mid-90s American dream. The 16 locations are designed for repetition and social choreography:

- Downtown’s Bay View Mall is the social hub. Five stores, fitting rooms with mirrors, and a Sam & Libby’s clothing boutique reflect real 90s retailers (Limited Too, Oshman’s).

- Madison High School has five classrooms: music, art, math, science, English—each with unique teachers (all played by the same man, a glaring flaw).

- Oyster Bay Arcade houses mini-games and is the game’s mini-game engine.

- Halsey’s Farm (Brett’s) and Nelson’s House (Derrick’s) imply class diversity—rural vs. urban, jock vs. scholar.

The realism of sets is staggering for 1995. Branded storefronts, parking lots, neon signs, drive-through menus—every detail feels lived-in.

Visual Direction: FMV as a Cultural Mirror

The FMV production values are uneven:

– Highs: Actor expressions, wardrobe, location variety, makeup continuity (you see the player’s virtual makeup in mirrors).

– Lows: Lighting inconsistencies, awkward editing, some actors seem uncomfortable reading from cue cards off-camera.

But the performances are surprisingly good. The young actors—many from Albuquerque’s local theater groups—deliver believable awkwardness, teenage crushes, and social anxiety. The sex scenes are nonexistent, but the chemistry is real.

Sound Design & Music: A New Mexico Soundtrack

The game includes a bonus music CD with 100+ tracks from:

– Poet, Cool Notes, Strawberry Zots (New Mexico bands)

– Tee Green (UK)

– Original tracks by Jean Rene De Rascon

Additionally, the in-game interface uses diegetic sounds:

– Voicemail dialing

– Car door slams

– Prom music (wedding-reel tracks)

– Jingle for Limited Too

Critically, no voice acting—dialogue is FMV mouth movements synced to audio, a limitation of FMV’s non-localization.

The music video for “And You” by Strawberry Zots is included—a surreal, low-budget ’90s clip. It’s a jarring artifact, but adds flavor.

The Physical Package: Beyond the Discs

The box is a cultural treasure (archived at Internet Archive):

– Makeup tips booklet (“Look on the Bright Side”)

– Pink breast cancer ribbon

– Internet access package (early web integration!)

– Coupons for real products

This blurs the line between game and commercial campaign—a meta-commentary on how girls were marketed to in the ’90s.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception: Polarized from Launch (1995–1997)

| Outlet | Score | Verdict |

|---|---|---|

| High Score (Swedish) | 100% | “Riktiga skådisar som agerar… Digi-filmer blandas med spelelement.” (Real actors… mixes with games) |

| Coming Soon Magazine | 82% | “Designated with the female player in mind.” |

| SuperKids | 80% | “Very forgiving about… disc swapping.” |

| Power Unlimited | 80% | “Like 90210… Echt wat voor de fans.” (For real fans) |

| PC Joker | 51% | “Hausbackene Spielablauf… Abfuhr.” (Home-dry gameplay… shut down) |

| Electric Playground | 30% | “Cardboard creation… exudes the depth of a puddle.” |

| World Village | 60% | “Recommend for girls 10–15.” |

The 69% critic average hides a tale of two reviews: European and parenting-friendly outlets loved it. U.S. tech-focused sites hated it.

Commercial Performance: A Quiet Blockbuster

- 40,000 units sold by 1998 (per GameSpot)

- Over 80,000 lifetime (per Her Interactive)

- $1.5 million budget (per Chicago Tribune, Jan 1996)

- Break-even achieved—a rarity for niche games

No major publishers distributed it. It was sold at Toys ‘R’ Us, B. Dalton, and specialty software stores.

The Expansion: McKenzie & Co.: More Friends (1996)

- 3-CD expansion: James (biker) and Aaron (vegan animal rights activist)

- Showed ambition: new romance, new social roles

- Aaron’s inclusion—a boy who doesn’t focus on dating, but activism—was quietly progressive

Evolution of Reputation: From “Depressed” to “Dated”

- 1999: Salon called it “much-reviled”—a punchline.

- 2010s: Reassessed. PC Gamer (2021) published a crapshoot retrospective, noting it was “fun for the actors” and “mildly entertaining” but “a nightmare of disc swaps.”

- 2020s: A cult artifact. Google Arts & Culture added it. MobyGames and NDW have walkthroughs. On BacklogGD, one player wrote: “This game was more wholesome than I expected.”

Influence & Lineage

Her Interactive’s next franchise—Nancy Drew: Stay Tuned for Danger (1998)—would evolve the same blueprint into mystery adventures with social drama, selling over 10 million copies.

Modern games inspired by its spirit include:

– Life is Strange (2015): Choice, consequence, female lead

– Florence (2018): Romance, mini-games, emotional journey

– Spiritfarer (2020): Emotional narration, quiet moments

– Telltale’s games: FMV storytelling legacy

It also paved the way for “girl games” despite the backlash—Bratz, Barbie, Alice: Madness Returns, and even Stardew Valley owe a debt to its proof of market.

Conclusion

McKenzie & Co. is not a flawless game. Its FMV is crude, its mechanics limited, its central goal dated, its gender politics ambivalent. It is not The Legend of Zelda. It is not Chrono Trigger. It is not even Day of the Tentacle.

But it is one of the most significant games of the 1990s—not for its technology, but for its cultural audacity.

At a time when the industry wrote girls off as an audience, McKenzie & Co. said: “You are here. You matter. Your life is a story worth telling.”

It did not invent girl gamers, but it gave them a mirror—for the first time, a game that let them run a bedroom, try on makeup, call their crush, and navigate the prom—not as a villain, but as a heroine.

The backlash was inevitable. Critics mocked its “pink overload”, its “makeup and shopping” focus. But this was precisely the point. The game did not apologize for being for girls. It leaned into it. It was unapologetically pastel, sparkly, and proud.

And for the 80,000 girls who bought it—it worked. They took Kim and Carly into their lives, passed exams, went on dates, failed, restarted, and tried again. They suffered the horror of disc swapping because the payoff—that yearbook photo, that limo ride, that prom night—was worth it.

McKenzie & Co. is not a great game. But it is a necessary game. Not because it was perfect, but because it dared to exist—in a world that told girls they had no place in the game.

Its legacy is not in sales charts—it’s in the thousands of young women who played it, and realized: “I can be the player, too.”

In the end, McKenzie & Co. was not just a game about high school.

It was a game about being seen.

And in that, it succeeded—beyond critique, beyond time, beyond the dull metallic clatter of swapping CDs.

RATING: ★★★★☆ (4/5) – Not for its quality, but for its courage. A flawed monument to inclusion. A vital piece of gaming history.