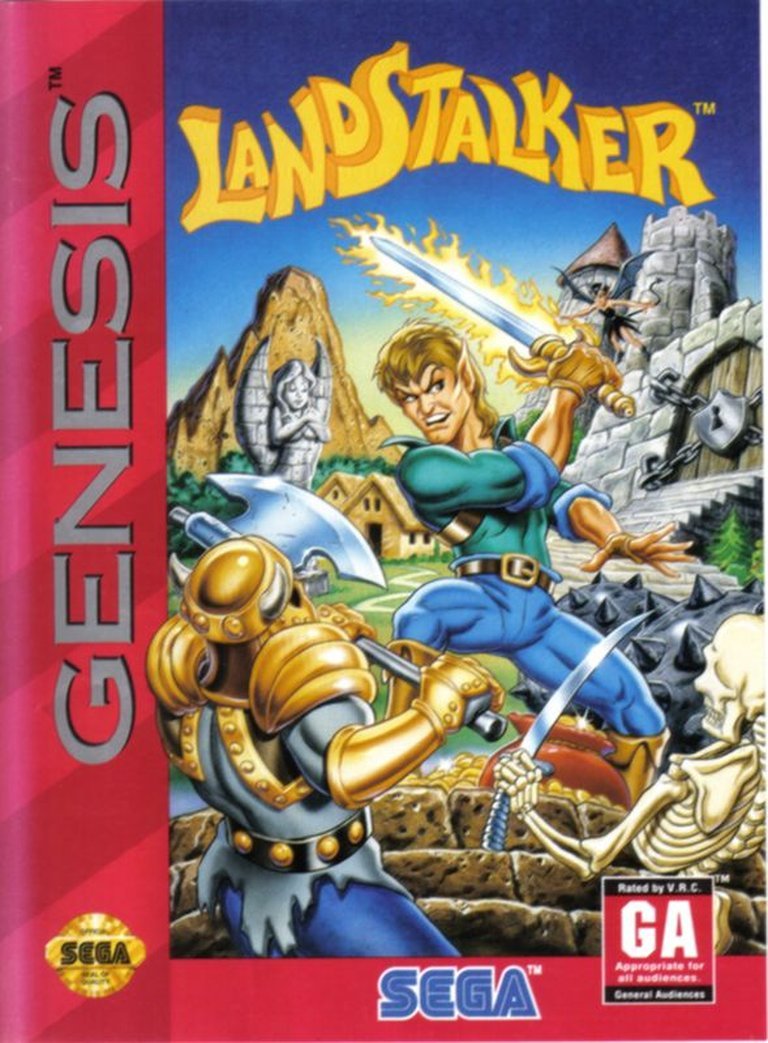

- Release Year: 1992

- Platforms: Genesis, Linux, Macintosh, Wii, Windows

- Publisher: SEGA Enterprises Ltd., SEGA Europe Ltd., SEGA of America, Inc., Tec Toy Indústria de Brinquedos S.A.

- Developer: Climax Entertainment

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Puzzle elements, RPG elements

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 88/100

Description

In Landstalker, players follow the adventures of Nigel, an experienced treasure hunter, as he teams up with a wood nymph named Friday to find the mysterious treasure of King Nole. Set in a fantasy world, the game unfolds across dungeon-like environments where players engage in action-packed platforming, intricate puzzle-solving, and feature light role-playing elements. Through isometric 2D visuals, players navigate various landscapes, battle monsters, overcome challenges, and explore vibrant towns while acquiring better equipment and completing optional quests, making for a richly immersive 30-hour journey filled with adventure and mystery.

Gameplay Videos

Landstalker Free Download

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : Landstalker was not content with that. Instead, it manages to actually be a really good story with genuinely funny lines.

mobygames.com (88/100): A must for anyone who can lay thier hands on it.

metacritic.com : The best game of Mega Drive / Genesis.

Landstalker: Review

Introduction: A Cult Classic That Defied Conventions

In the shadow of Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda, Sega’s 1992 isometric action-adventure Landstalker dared to be different. While countless games in the early 90s borrowed from Link’s template—top-down exploration, intuitive sword combat, and a heroic “save-the-princess” quest—Landstalker pivoted toward a fresh formula: isometric projection, platforming, item-slinging puzzle design, and a self-aware treasure hunter as its protagonist. Developed by the ambitious Climax Entertainment and released mere months after The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, it carved a legacy as Sega’s answer to the Zelda-style action-RPG, but one differentiated by its obsessive precision, goofy irreverence, and an art style that married fantasy whimsy with the hard edges of 16-bit technical limitations.

Thesis: Landstalker is not just an overlooked 16-bit gem; it is a masterclass in risk-taking design, an artifact of creative audacity executed (mostly) flawlessly within technological confines, and a game whose influence persists—even if its successors often fail to capture its unique magic. Though critically adored at launch, it has since evolved into a cult phenomenon, revered by retro enthusiasts, game designers, and mechanical critics. Its flaws—most notably its isometric spatial disorientation—are not bugs, but features: foundational pillars of its identity. To dismiss it for control quirks is to miss the forest of its ambition for the trees of its interface.

Development History & Context: How a Studio Carved Its Own Destiny

To understand Landstalker, one must trace the ambitions of Climax Entertainment, a young studio that had already co-designed two of Sega’s early RPG hits: Shining in the Darkness (1991) and Shining Force (1992). Led by Kan Naito (programming head) and Kenji Orimo (director/designer), the team sought to break free from the Shining series’ turn-based RPG mold and forge an action-RPG with greater interactivity and environmental agency. Unlike Camelot’s planning-focused work on Shining Force, Climax wanted a game where the player interacts, a world where throwing a pot isn’t just a command, but a legitimate tool for progress.

Originally titled Shining Rogue, the split between Climax and Sega’s internal teams (who retained the Shining branding) allowed the project to shed its corporate constraints and pursue radical design choices. The decision to adopt an isometric perspective—rare in the JRPG dominated Japanese market at the time—was inspired by British computer games like Ultimate’s Knightlore, powering a vision of depth and dimension. But the Genesis was built for side-scrollers; isometric art demanded brute-force sprite scaling, a frame-by-frame sleight-of-hand to make the illusion seem 3D. As MobyGames documents, 46 contributors—many with CG credits—spent agonizing months hand-drawving every sprite at three angles (N, NE, E) to ensure consistency.

Technological Constraints and Creative Adaptations:

– 16-MB cartridge (a massive budget for games of its era) allowed for expansive dungeons, 9 towns, and 20+ hours of gameplay.

– The Genesis’s lack of true diagonal input necessitated D-pad diagonal pressing for movement—a compromise that would become legendary for its frustration but also its deliberate unorthodoxy.

– Music by Motoaki Takenouchi—a composer unafraid to blend jazzy up-beats with dungeon dirges—used the YM2612 to full emotional effect, crafting a soundtrack that’s both iconic and atmospherically layered.

– Full Japanese anime-style pixel art by Yoshitaka Tamaki and Hidehiro Yoshida diverged from the dour, Tolkien-esque art of its US peers. Sprites were large, chunky, and cartoonish, an aesthetic later seen in Treasure’s Light Crusader (as noted in GameFan’s 1993 review).

The release context was seismic: October 30, 1992 (JP), followed by North America and Europe in late 1993. The Genesis was in full swing against the SNES, and while Sega pushed racing (Sonic, OutRun) and action (Golden Axe), Landstalker represented a strategic gamble—a high-barrier-to-entry, unconventional gem that targeted the RPG niche instead of the mass market. Sega dared to release an adventure with no magic, no level-ups, and a hero who was not a chosen one but a cynical, sarcastic elf.

As Sega-16’s history essay notes: “Neither Naito nor Nishigaki had intended to compete with Link, and to pair the two seemed slightly ridiculous, given just how different they actually were.” This distinction—difference by design—is Landstalker’s greatest triumph.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Rogue’s Progress Through Butts and Bears

Landstalker’s story—crafted by Shinya Nishigaki—is a deceptively intricate web of dark comedy, conspiracy, and existential irony, hidden beneath the facade of a standard treasure-hunt quest. Unlike games of the era that treated narrative as a checklist (find X, save Y, defeat Z), Landstalker tells a story about illusion, power, and the cost of legacy.

Act I: The Treacherous Bait (Jypta Ruins to Massan)

We open with Nigel, an 88-year-old elf (who looks 18), raiding the Jypta Ruins to steal the Statue of Jypta. The boulder puzzle that climaxes this act is less about danger and more about establishing Nigel’s skill—he is a professional, not a hero. After selling the statue, he’s accosted by Friday, a sucubus-turned-wood-nymph in the Japanese version (bowdlerized to “fairy” in the west due to content cuts). She claims to “feel” the location of King Nole’s treasure, a MacGuffin that sets the plot in motion. But here’s the thematic seed: she doesn’t know. She’s guessing. The narrative’s foundation is built on uncertainty and intuition, not prophecy.

Act II: The Bear Proxy War (Massan/Gumi to Ryuma)

Nigel’s treatment of the bear tribes—Massan (red-furred) and Gumi (yellow-furred)—reveals his moral complexity. He doesn’t care about tribal conflict; he knows Fara’s sacrifice is a setup for a clue. The shrine sequence—where Nigel breaks the “curse” by discovering the Tambari gypsies are the true villains—is a clever subversion of tropes. The evil isn’t beasts, butbad men—genocide disguised as tradition.

Then comes Ryuma, a thief-ridden town. Nigel rescues the mayor, finds a dragon lithograph, and is ambushed by the Goldfish Poop Gang: Kayla, Wally, and Ink (TV Tropes). They’re not threats—they’re Running Gags, appearing only to be comically tortured (piano dropped on them, splash into lakes). Their presence is pure British slapstick, a tonic to the game’s darker conspiracies.

Act III: The Duke’s Gambit (Mercator to Verla)

Mercator is the game’s narrative nexus. The Duke hires Nigel to defeat Mir, the wizard-in-the-tower, threatening taxes. The dungeon puzzles are brutal, but the twist is genius: Mir isn’t evil—he’s trapped, and the Duke is his brother, using him as a scapegoat. The Brotherhood of Mercator is a fascist accessories-to-power conspiracy, extorting citizens through terror.

Nigel escapes after learning the truth, but the Duke’s AI pattern—a stilted path to the captain’s quarters where he yells “I’m coming, captain!”—is a hilarious, satirical portrait of a corrupt administrator. The divorce between his staid dialogue and giddiness is absurd.

Act IV: The Betrayal and the Maze (Verla to King Nole’s Labyrinth)

Verla is a dystopian ruin, enslaved by the Duke’s forces to dig for treasure. Nigel frees them, earns the Legendary Sword, and faces Zak, the Duke’s Drakkonian (dragon-man) henchman. Zak is one of the game’s few noble foes; he later teams up with Nigel, not because he’s good, but because he’s willing to let skill decide the world’s order.

The final trek to King Nole’s underground involves Teleport Spam, Spikes of Doom, and a 4-button simultaneous puzzle solvable only by stacking blocks—a Waiting Puzzle that forces the player to wait for switches to open. It’s not just hard; it’s philosophically punishing: progress requires patience, not power.

Act V: The Anti-Climax (Gola and the Treasure)

The final battle with Gola, King Nole’s “Dragon God,” sets up the game’s ultimate thesis: Treasure is Illusion. Whether the treasure evaporates (JP/EU) or spins up to quintuple digits (US) (segments from *segaretro and postgamecontent), the result is the same: Nigel wasn’t after gold. He was after adventure, partnership, and a life of meaning.

Friday, the exposition fairy (TV Tropes), is not just helper; she’s his “Girl Friday”—a literal nickname—and their dynamic, where she teasingly calls him “little brother” (Andrew Fisher review), is one of the few in JRPGs where the companion is the emotional core.

The ending’s brevity—especially in the Japanese version’s vanished gold—is not a flaw but a bold narrative choice. After In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida (referenced in the password: “In-nah Gad’da da V’idda”) tears the world, the real achievement is not the treasure, but the act of contending with it.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Machinery of a Mad Genius

Landstalker is a system of engineered tension: the closer you get to victory, the more the game tests your spatial logic, item management, and patience.

Core Controls: Isometric as “Lizard Logic”

- Movement: Mariocade D-pad relies on diagonal presses (up+right for “east”). No digital-axis isolation. This forces the player into a mindset of 2D projection, not true 3D thinking.

- Jumping: Platforming is where this logic fails most. Jumps require hitting edges at precise angles. The lack of shadows—no sprite drop—forces lead-and-guess. You must feel with your sword’s length, not your eyes.

- Combat: Nigel’s sword is a wild horizontal arc, not a directional thrust. Enemies are hitboxed entities, not tile-aligned. Combat is “positional,” not “melee.” Magic swords (Fire, Thunder, Ice) add splash damage, but no healing magic. The game bans easy healing via Eke-Eke herbs: Friday automatically revives Nigel, but only once per area.

Puzzle & Progression Design: Tools Over Magic

- Item-Throwing: Levers, switches, and platforms can be activated by throwing pots, crates, or even enemies. One optional puzzle requires knocking a spider into a pressure plate.

- Cranium Ride: Hit anything—NPCs, dogs, gnomes—to stand atop their heads. Used in five puzzles.

- Crystals and Crypt Puzzles: The crypt of Mercator has 10-word puzzles where dead names (e.g., “Larcen E.”) hint at riddles (spelling puzzles). One puzzle requires waiting 30 seconds—true “waiting”.

- Town Integration: Towns are not static hubs. In Kazalt, dwarves offer optional quests (e.g., break the witch’s curse for comic books). The variety store in Mercator sells joke items costing 100,000 gold—4x the game’s total.

RPG-Lite Progression: “Cultivation” Over “Leveling”

No experience, no stat progression—instead, the game adds:

– Life Stocks: Permanent +4 HP, bought or found (6 total).

– Keyed progression: Golden Axe, Sunstone, etc., open new areas.

– Sword upgrades: Gaia’s Sword (final) grants slash radius, not power.

The loop is: Puzzle > Item > Area Unlock > Repeat.

Depth Perplexion as Design Philosophy

As Post Game Content observed, Climax didn’t hide its weaknesses—they weaponized them. Isometric Depth Perplexion—where platforms are invisible, pits are unblockable, and doors lead to dead ends—is not a bug. It’s psychological bootlegging. You must ask, “Where is ‘here’?” The game exploits the brain’s inability to process 2D proxies for 3D space. The Greenmaze dungeon’s obfuscated platforms (causing the “reviled” status per sega-16) is intentional: a survival horror filter.

The 4D save system (4 slots) encouraged multiple playthroughs, but also LARPing recovery—restarting after death (no death penalties) is rewarded with muscle memory.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Choncology of a Fake Archipelago

Art Direction: Anime Meets Steampunk

Hidehiro Yoshida’s vision merged anime cutscenes.

- Screens: Every screen is meticulously crowded—cages, crates, trees—to hide secrets (Guide Dang It! sections).

- Color Palette: Fields are not monochrome; blues, greens, and purples merge in a low-contrast gradient to suggest mood, not realism.

- Character Design: The “chunky” style (noted by GameFan) isn’t archaic—it’s stylized clarity. Enemies like skeletons, golems, and Unicorn Bleeders are distinct, not abstracted.

The Music of Motoaki Takenouchi: A Chef’s Knife

- Overworld: “Gumi Road” is bouncy, chip-tune innocence.

- Dungeons: “Mt. Kress” is a nervy, ascending synth-choral dread. “King Nole’s Garden” is an eerie, reverb-heavy taiko loop.

- Boss theme: There isn’t one—battles use ambient music, making encounters feel organic, not epic. The only exception is Gola’s fight, with a heavy metal protest that’s over in seconds.

- Friday’s Theme: A mischievous xylophone jingle that’s stuck in your head.

As MobyGames reviewers noted: “Landstalker’s score is so good I searched for the soundtrack… to no avail.” The Genesis’s FM synthesis, when pushed, could scream.

Interactivity as World-Building

The world speaks through interaction: pushing a lever in Mir’s tower doesn’t just open a door—it breaks a chain mechanism, pulling scrap metal. The detailful, destructible environments (300+ sprite sheets) turn the island into a giant physics engine.

Reception & Legacy: From Critic Darling to Historical Prototype

Initial Reception: Near-Perfect, But Polarizing

At launch, Landstalker was explosively praised but commercially niche:

– Foreign Critics (RPGFan, GameFan, Joystick): 99%–97% (e.g., GameFan: “Climax gets a standing ovation for this playable masterpiece.”)

– Japanese Critics (Beep! MegaDrive): 8/10—slightly more reserved, citing control quirks.

– NWC (Next Power Game) and Dragon 217: Split—NWC gave it 9/10, Dragon’s Jay & Dee gave it 3.5/5, criticizing its “craftsman” lack of polish.

As MobaGames shows, its 88% metacritic (25 reviews) and #18 Genesis ranking (mobygames) reflect admiration, but not mass appeal.

The Evolution of a Cult: 2000–Present

Post-2000, Landstalker entered the retrogaming canon:

– Wii VC (2007) and Steam (2011): Revival attempts, but poorly marketed.

– Critical Re-appraisal: Magnetic Fields (SEGA-16): “One of the Genesis’s greatest cult favorites.”

– Spiritual Successors: Dark Savior (1995, Saturn) and Alundra (1995, PSX) copied its systems, but lacked its soul (sega-16). Alundra is its spiritual heir; Legacy of Kain: Defiance (2003) borrowed its isometric tension.

– Influence: Landstalker inspired The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker’s system menus (item menus at screen-top), and Dark Souls’ labyrinthine backtracking. Darksiders (2010) uses its item-based progression.

– Licensing: Nigel in Time Stalkers (1999) wasn’t a cameo—it was an official acknowledgment of his mythic status.

Missed Opportunities – The Lost Legacy

- Cancelled PSP Remake (2005): Naito’s planned remake—3D, full-blown—was cancelled. Rumors say Sony deemed it “too niche.”

- Lady Stalker (1995): A SNES pseudo-sequel that removed jumping to “fix” controls. But it lost the soul (sega-16).

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece That Demanded More Than It Could Deliver

Landstalker is the greatest game Sega never pushed. It is a masterpiece of constraint, where every frame, note, and control choice is informed by paradox—the rigid 2D grid attempting to express a dreaming 3D world. Its controls are brutal, its ending abrupt, its puzzles sometimes obtuse. But these flaws are not failings—they are ideological choices.

As the Lord-Spencer review notes, it’s a game that confidently goes forward as its own thing. It’s not Zelda with a twist. It’s a rejection of Zelda’s orthodoxy. Nigel is not a chosen one. He’s a thief. The world is not lush and pure. It’s corrupted. The quest isn’t about saving the princess. It’s about finding yourself in the hunt.

In video game history, it stands as proof that innovation can arise from art, not tech. This is not the first isometric game—Ultimate did it first—but it is the first to embrace the aesthetic as identity. To play Landstalker is to be invited to a foreign land—to walk a knife’s edge between genius and masochism, between absurdity and profundity.

Verdict: 9.4/10

Landstalker is not the best game of the 16-bit era. But it is the purest. It is a time capsule of a studio’s audacity, a game where every jaunt, jump, and sword-swing resonates with the thrill of being utterly different. Like the treasure of King Nole, it doesn’t last—but the journey to find it, to feel the adventure, is eternal.

“Achievement is not the treasure. The treasure is the quest.” – Lord-Spencer, GameFAQs