- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

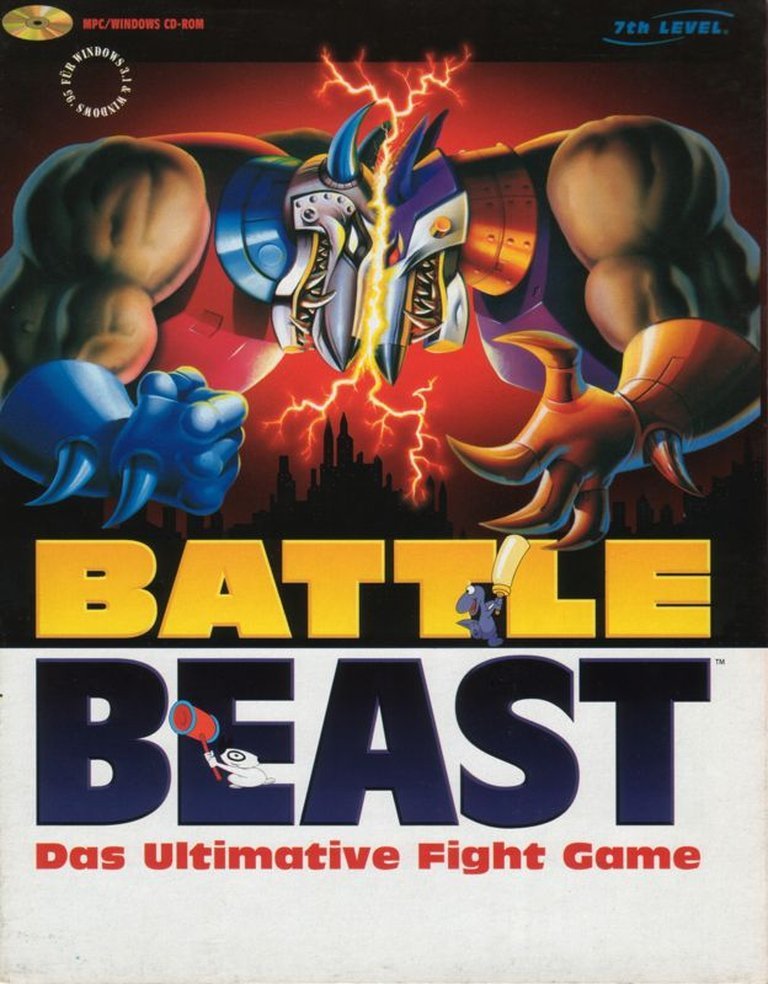

- Publisher: 7th Level, Inc., BMG Interactive Entertainment

- Developer: 7th Level, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Co-op, LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Bonus rooms, Fighting, Maze racing, Mini-games

- Setting: Cartoon, Transforming robots

- Average Score: 68/100

Description

Battle Beast is a quirky, cartoonish fighting game released in 1995 for Windows and Macintosh, where players control cute but deadly animals that transform into powerful robotic combatants, battling in side-view arenas reminiscent of titles like Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter. Developed by 7th Level, Inc. and published by BMG Interactive, the game stands out with its whimsical art style, animated visuals, and inclusion of intermission mini-games such as maze races and bonus rooms filled with collectibles. Designed with optimization for the newly launched Windows 95, Battle Beast supported multiplayer options including LAN, modem, split-screen, and null-modem connections, offering a unique blend of accessible arcade combat and lighthearted variety, all wrapped in a commercial CD-ROM package praised for its charm despite slightly sluggish gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Battle Beast Free Download

PC

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (69/100): It’s a decent fighting game, but one with significant flaws.

mobygames.com (67/100): Average score: 67% (based on 12 ratings)

oldpcgaming.net : Battle Beast looks great as a cartoon, and plays about the same as well.

Battle Beast: Review

A curious confluence of 90s pop culture obsessions—Beast Wars: Transformers, Mortal Kombat, Silicon Valley hubris, and early consumer Windows 95 software bundling—Battle Beast (1995) is a game that defies easy categorization or immediate dismissal. Developed by the now-defunct 7th Level, published by BMG Interactive, and released at the absolute zenith of the 16-bit-to-32-bit PC transition, Battle Beast stands as a bold, bizarre, and uneven experiment in thematic fusion and technical ambition. Its legacy is one of unrealized potential, of a game that looked incredible on the box and during idle splash screens but stumbled under the weight of its own aggressive controls, repetitive structure, and the immense shadow of its contemporaries.

This review is an exhaustive archaeological excavation of Battle Beast: its visionary studio, its tonal paradox, its mechanical frustrations, its visual flourish, its reception, and its enduring, if niche, place in the pantheon of late-90s experimental games. My central thesis is this: Battle Beast is not a forgotten classic, but a fascinating failure—one that uniquely encapsulates the exuberant, chaotic energy of the mid-90s PC scene, where innovation often ran ahead of execution.

Development History & Context

The Studio: 7th Level and the Culture of Niche Innovation

7th Level was not your typical 90s game developer. Founded in 1993 in Santa Monica, California, their early work—Monty Python CD-ROMs (The Complete Waste of Time, The Quest for the Holy Grail)—established them as pioneers of interactive edutainment and comedic multimedia. Their goal was to create “entertainment that was fun and educational without being schlock.” This focus on narrative, humor, and presentation over rigid genre formulas became their brand identity.

By 1995, 7th Level was expanding aggressively. Battle Beast emerged during a period of rapid expansion, with 91 credited contributors (a huge number for the era) and a budget that reflected its ambitions. Unlike the lean teams behind Mortal Kombat or Street Fighter II, 7th Level invested heavily in art, animation, sound design, and comedic writing. The game used the “Topgun Playback Engine”, potentially an in-house tool co-developed by Don Moir and Doug Gillespie—a system reportedly optimized for Windows 95’s multimedia architecture, including full-motion video (FMV), CD audio, and early DirectDraw/DirectSound integration.

Windows 95: A Strategic Opening

Battle Beast was one of the first games specifically designed for Windows 95. It was bundled on OEM machines, marketed as a “killer app” for the new OS and its plug-and-play multimedia support. The game’s box art screamed “The Ultimate Fight Game – Optimized for Windows 95!”—a slick, high-gloss design with cartoon animals and explosive motion lines—distinct from the gritty, pixel-art covers of its competitors. This positioning was not accidental. BMG and 7th Level wanted to associate their brand with the future of PC gaming.

This timing was critical. The launch of Windows 95 on August 24, 1995, created a “killer app” vacuum—consumers wanted flashy new software to justify upgrading their hardware. Fighting games were the genre of the moment. With Mortal Kombat 3 dominating arcades and Street Fighter Alpha on the horizon, a PC-exclusive, cartoonish alternative with “advanced Windows features” had a window. 7th Level aimed to leverage Windows 95’s superior GUI, CD-ROM support, and multimedia capabilities to deliver a smoother, more visually rich experience than DOS alternatives.

The Gaming Landscape in 1995

1995 was the pinnacle of the “fighting game arms race.” Titles were being judged on:

– Special moves: Flashy combos and cinematics.

– Gore and “attitude”: Mortal Kombat‘s fatalities, Primal Rage‘s dinosaur execution moves.

– Local play: Two-player head-to-head was still king.

– Platform exclusivity: PC developers were struggling to match console fluidity.

Battle Beast entered this landscape with a radical twist: adorable animals that transform into robotic combatants. It wasn’t just a Street Fighter clone with a new skin. It was a thematic inversion—replacing grim warriors with cuddly puppies, kittens, and turtles that became chrome-plated, laser-firing tanks.

Yet, it arrived at the edge of obsolescence. Consoles had moved to 32-bit (Sony PlayStation) and 24-bit (Saturn) systems, capable of 3D models (initial attempts with Killing Time) and smoother animation. The PC was still playing catch-up with 3D accelerators (3Dfx Voodoo had not yet launched). Battle Beast would be a 2D, sprite-based side-scroller, but it aimed to compete via art direction, humor, and technical polish.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Premise: A Whimsical War on Toads

The narrative of Battle Beast is ludicrous, charming, and structurally clever.

The evil Toadman is breeding toads and setting them loose on the city. The battle beasts, cute pets normally, but vicious home protection robots when needed, protect the city. Toadman infiltrates the factory where the beasts are made in order to reprogram the beasts to fight each other instead of his toads. He is caught mid act, so he only got to the “fight each other” part.

This is absolutely genius in its absurdity. It flips the traditional “curse turns men into beasts” trope into a reverse transformation: cute animals → robotic war machines. The core premise—a pet owner’s dream turned into a city-wide crisis—is a delightful inversion of power. These aren’t warriors; they’re house pets drafted into war.

Thematic Contradictions

Battle Beast operates on polarizing but intentional dichotomy:

-

Whimsy vs. Violence: The visuals are overwhelmingly cartoonish—colorful, squishy animals (e.g., Sparky the Dog, Curi the Fish), exaggerated facial expressions, and slapstick animations. Yet the action involves laser blasts, explosive projectiles, and heavy melee strikes. The contrast is jarring but intentional: it’s satire of the genre’s machismo. The battle isn’t between elite warriors—it’s between a mutant puppy and a bloodthirsty turtle.

-

Home Security vs. Total Destruction: The beasts are “fierce home protection robots,” suggesting a punk aesthetic of suburban militarization. Think The Jetsons meets Mad Max. They’re not soldiers; they’re tricked-out toys gone rogue.

-

Comedy of Errors: The plot hinges on a failed reprogramming attempt. Toadman almost succeeds—changed “protect property” to “fight each other”—but didn’t save the command. It’s a comedy of ineptitude, where the real tragedy isn’t destruction, but a wetware bug.

Characters: Pets as Mythic Beings

The six playable beasts (each with an animal and robot form) are mythic forces reimagined as household creatures:

– Sparky (Dog → Spaticus): A Rottweiler-tank hybrid, aggressive and fast.

– Curi (Fish → Curapesh): A robotic anglerfish with sonar and harpoons.

– Bermi (Rat → Vermian): A cyber-rat with poison darts and burrowing.

– Nasata (Dinosaur → Nasata): A T-Rex mech with seismic roars.

– Tokuda (Rhinoceros → Tokuda): A rhino-tank with a hazmat cannon.

– Moltis (Turtle → Morden): A shelled fortress with a cannon and shield.

Each has a winking personality—Sparky barks excitedly, Curi grins with cruel glee, Bermi scuttles with paranoid haste. Their pre-fight idles (which bore the player during 20-second timers) are filled with barking, chirping, and comical grunts. The voice acting (by Maurice LaMarche, Michael Lynch, Michael Sorich) is excellent and over-the-top, with deep, metallic robot voices contrasted with high-pitched, squeaky animal calls.

Toadman: Villain as Dandy Militant

The final boss, Toadman, is a brilliant piece of camp. He wears a tuxedo mask (a literal tuxedo cut into a mask), speaks in a british-accented baritone, and treats frog armies like an army of toad-shaped henchmen. His stage is a flask-filled laboratory with bubbling green goo. He fights as a large toad who transforms into a toad-shaped robot—a crude, boxy machine that fires purple saliva bullets. This final form is deliberately less impressive than the other beasts, underscoring his ineffectual villainy.

The script, written by Linda Garibay and Jeff English, is full of dark humor. When introduced, he complains about “these blasted pets,” and during his victory animation, he cackles maniacally while frogs eat the player.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Sewer Stages & Boss Fights

The single-player Adventure mode is a linear progression through nine sewers. Each is a side-scrolling arena with hazards:

– Overhead pipes that drop acid rain.

– Toxic sludge pits.

– Explosive barrels.

– Falling manhole covers.

The core mechanic is the 20-second idling phase before each fight. Both players spawn at the far ends, separated by a sewer gradient. They have 20 seconds to:

– Kill roaming toads (score points).

– Pick up power-ups (health, energy).

– Find secret tunnels leading to bonus rooms (maze races, “Whack-a-Toad” minigames).

This idling phase is the game’s most innovative (if polarizing) mechanic. It transforms each fight into a mini-competition—a race to collect loot, destroy mobs, and scout for secrets. In theory, it encourages exploration and risk-taking. In practice, it breaks the flow of the combat. Many players found it tedious or distracting. Yet, it’s brilliant design—it adds player agency and strategy to a genre increasingly dominated by reflex-only play.

Combat System: A Clunky Beast

The combat itself is deeply frustrating. It’s a 2D side-scroller with 33 different inputs (a massive number for the era), including:

– Multi-key combos for special moves.

– Dual action buttons (Attack, Special).

– Directional inputs for weapon use.

The controls were universally panned. Critic Entertainment Weekly called the joystick commands “unresponsive.” PC Gamer noted “sluggish movement.” CVG called the game “tad sluggish.” My Abandonware’s infamous review said the character looked like a “dysfunctional drunkard” hopping around.

Why so flawed?

– Keyboard as primary input: Designed for keyboard or joystick, but keyboard requires finger gymnastics. Most moves need 3-4 simultaneous keys.

– Poor responsiveness: Animation frames block input mid-move.

– Collision detection issues: Attacks often miss despite visually hitting the target.

– Over-abundance of moves: 33 operations, 100+ “extra moves,” but no scaling. Many moves are useless outside of combos.

Transformation Mechanic: The Heart of Combat

The animal/robot switch is the game’s saving grace. Each character can transform at will:

– Animal Form: Faster, smaller hitbox, can gather power-ups, but weak attacks.

– Battle Beast Form: Slower, massive hitbox, strong attacks and specials, but can’t interact with ground objects.

This dual form creates a risk/reward dynamic:

– Transform early for sword fights, but you’ll miss health boosts.

– Stay in pet form to collect armor, but you’ll be easily defeated.

This mechanic mitigates the control issues. Smart players use hit-and-run, transforming just before a combo connects. It adds depth to what otherwise feels like a button-masher.

Progression & Multiplayer

- No tournament mode: The lack of a saveable ladder removes replay value. After beating Toadman, it’s back to the start.

- No AI difficulty scaling: The final boss is cheaply difficult, but early fights are trivially easy.

- Multiplayer brilliance: The head-to-head and co-op modes are excellent. Up to two players via same screen, split-screen, LAN, modem, or null-modem. The 20-second idling phase becomes a friendship destroyer, as players race to collect power-ups and stall with alarm clocks.

StrategyWiki confirms a co-op mode where two player beasts can both progress through the campaign, a rare feature in 1995.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction: Cartoon Noir Meets Techno-Punk

Battle Beast is a visual masterclass. 7th Level’s background in monty python multimedia shows in every frame. The art style—hand-drawn animations at 800×600 SVGA—is a hyper-caffeinated Looney Tunes meets Beast Wars.

- Characters: Rotoscoped animators with overexaggerated expressions. Sparky’s transformation animation shows him roaring and morphing into cables, gears, and pistons with cinematic zooms.

- Environments: Sewers are multi-layered with mechanical greebles, dripping pipes, and neon signs (“SEWER 4: SPEED KING BATTLE”). Bonus rooms are absurd—a toad rodeo, a maze race with floating clocks.

- UI: Cartoonish and functional. Health bars are animated gas gauges, energy meters glow, and menus pop with sound effects.

Animation & Foreshadowing

The splash screen sequence—where the game idles and plays cinematic fight scenes—is legendary. As noted by GameSkinny’s Erik Greeny, these sequences (“watching pre-recorded gameplay sequences that would roll when I didn’t do anything”) were experienced like short films, not menus. This intentional “movie mode”—a proto-Street Fighter II Turbo—showed off the animation quality, with full voice, music, and sound effects.

Sound & Music

- Music: Composed by Ron Wasserman (Power Rangers theme, VR Troopers), it’s a hybrid of techno, rock, and accordion. The main theme is upbeat and comical, a perfect fit for the tone. Stage music is up-tempo, with chipper melodies.

- Sound Design: Loudest elements are toad squishes, laser zaps, and robotic grunts. Transformation effects are electromagnetic hums and hydraulic hisses.

- Voice Acting: Top-tier. LaMarche (Mongol from Dexter’s Lab) delivers a perfect Toadman—hammy, theatrical, and menacing. The beast quips (“You’re toast, toad!”) are cartoonish and entertaining.

The audio is so good it almost tricks you into thinking the game is flawless—until you try to walk and attack at the same time.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception: A Divisive Figure

Battle Beast received a 67% average from 12 critics—a “flawed gem” score.

Positive Reviews:

– Computer Game Review: “92/88/89” – Highest rating. Praised animation, humor, and called it “Finally, a quality fight game worth owning.”

– Next Generation: “An incredibly fun and visually stunning fighting game” – 3/5 stars. Loved the “cute, humorous animation”.

– CVG (82%): “Stunning” presentation, “great sight gags”.

Negative Reviews:

– PC Gamer (69%): “Decent… with significant flaws” – Control issues, no tournament.

– Génération 4 (40%): “About as pleasant as a tank without hands” – Brutal controls.

– PC Joker (64%): “Lovely presentation, but sluggish and repetitive”.

The player score on MobyGames is just 2.4/5 (20 ratings), underscoring frustration with the controls.

Sales & Distribution

- Shipped 50,000 units (Wikipedia). While not a blockbuster, this was respectable for a niche PC title.

- Bundled with OEM Win95 PCs: Many players didn’t know they bought it—it was pre-installed on new desktops, a major distribution channel.

- Included in compilations: Battle Beast / Take Your Best Shot / Arcade America (1997), expanding reach.

Critical Reassessment

- GameSkinny (2014): Called it “one of the handful of games… truly worth checking out” and praised its “unabashedly cartoony nature”.

- My Abandonware: Despite panning the controls, admitted the art and music were “wonderful”.

- Community Nostalgia: On forums and Discord, players in their 30s and 40s recall Battle Beast as “that weird pet robot game from childhood”—a cult memory, not a forgotten classic.

Influence & Legacy

Battle Beast was not influential on gameplay. Its control system and progression scale poorly to modern play. Yet, its legacy is ethological, not mechanical:

- Genre Fusion: It pioneered the “cartoon vs. mecha” aesthetic before Pikmin, Zippy, or Metal Arms. The idea of adorable creatures in robotic war machines became common in 10 years post-launch.

- Narrative in Competitive Games: It proved humor and narrative could coexist with deathmatch, a lesson lost in the early 2000s but relearned in games like Overwatch or Titanfall.

- Multimedia Design: It showed the potential of Windows 95’s multimedia framework—FMV, CD audio, GUI integration—five years before DirectX matured.

It’s a canary in the coal mine—a 1995 experiment in how far you can push a 2D fighter without 3D animation.

Conclusion

Battle Beast is not a forgotten classic. It is a failed masterpiece.

It was released at the wrong time (1995, when 3D was the future), with the wrong control scheme (a keyboard nightmare in an era of arcade sticks), and the wrong tone (cartoonish in a market demanding Mortal Kombat levels of edginess). Yet, it was brilliantly designed for its time, using the strengths of the Windows 95 multimedia stack to deliver a graphically stunning, narratively rich, and tonally unique experience.

Its art, music, voice design, and thematic ambition are undeniable—it is one of the most visually polished 2D fighters of its era, and its concept remains fresh 30 years later. The robot-animal transformation is a brilliant twist on the genre, and the sewer stages, bonus rooms, and idling phases are inventive mechanics that reward exploration.

But the execution—the sluggish controls, the poor collision detection, the repetitive structure—undermine its brilliance. It is a game that is more fun to watch than to play. As described by OldAssGamer on MyAbandonware: “nice graphics for the time but the controls are sluggish and painful.”

Its place in history is as a footnote in the evolution of multimedia design, not as a hall-of-fame fighter. It doesn’t belong in the same category as Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, or Primal Rage. It belongs in the “What If?” game museum—next to Hotsword, Timeball, and Chrome (1995).

Verdict: 6.5/10.

A visually game-changing, mechanically broken, tonally unique experiment in 1995’s PC culture. It was ahead of its time in vision, but frozen in time by its execution. For historians, educators, and niche enthusiasts, Battle Beast is essential—for everyone else, it’s a cult oddity with the soul of a future classic trapped inside a clunky 1995 frame.

It’s a reminder that the most interesting games aren’t always the best, but the ones that dare to be something else. And in that, Battle Beast triumphs. It may not be the ultimate fight game, but it is, undeniably, the ultimate what-if.