- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Licensed 4U Limited

- Developer: Playrix LLC

- Genre: Compilation, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Falling block puzzle, Tile matching puzzle

Description

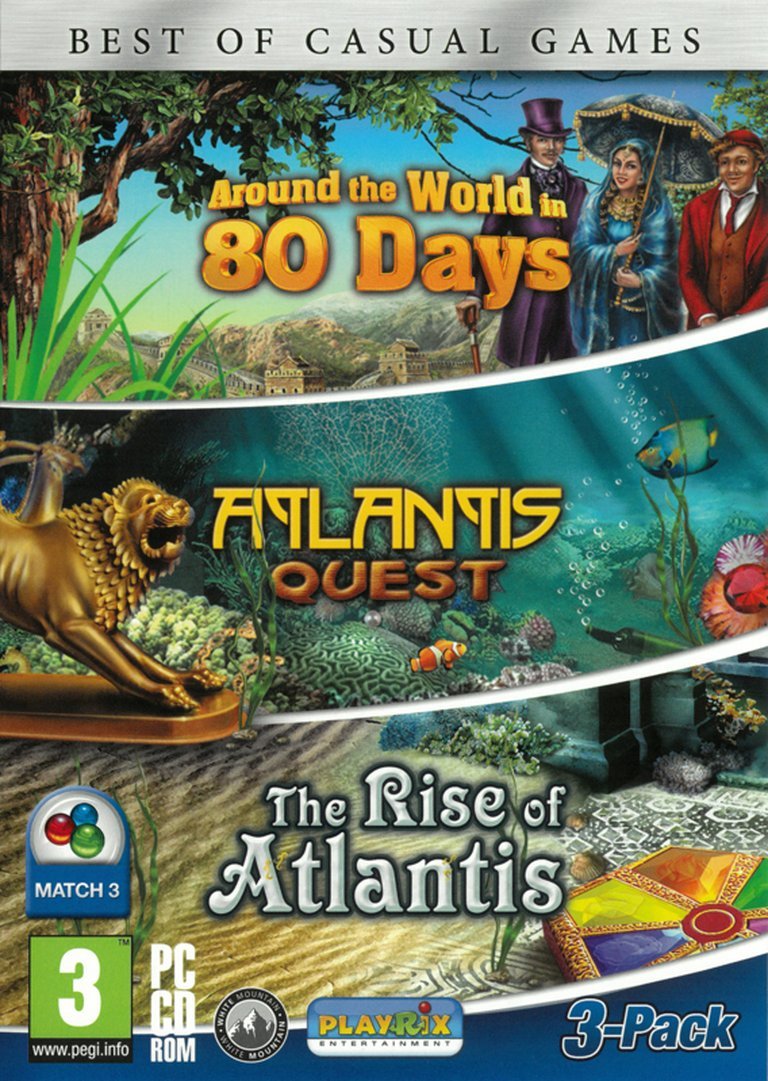

The Playrix Triple Pack is a compilation of three engaging puzzle games developed by Playrix LLC, bundled together for Windows in 2011. It includes ‘Around the World in 80 Days,’ a tile-matching adventure based on Jules Verne’s classic novel where players race across four continents; ‘The Rise of Atlantis,’ a falling-block puzzle game that tasks players with collecting artifacts across ancient civilizations to restore Atlantis; and ‘Atlantis Quest,’ another tile-matching journey set in the mythical underwater world. Presented in side-view, flip-screen format with point-and-click controls, each game offers unique power-ups, bonuses, and over 200 levels of challenging puzzle gameplay suitable for all ages.

Playrix Triple Pack: Review

1. Introduction: The Curious Case of a “Triple Pack” with an Identity Crisis

The Playrix Triple Pack presents a fascinating case study in the evolution and bundling practices of casual gaming. It is not a new game but a curated collection of three previously released titles from Playrix, LLC: Around the World in 80 Days (2008), The Rise of Atlantis (2007), and Atlantis Quest (2006), all re-released under one physical CD-ROM in 2011. This may sound like a standard value package, but a closer examination reveals a nuanced portrait of a rising casual game studio, Playrix LLC, attempting to consolidate its early bestsellers into a mainstream retail product at a critical juncture in the industry. Your thesis: While the Playrix Triple Pack contains three solid, deeply influential puzzle games from the peak of the “casual boom,” its significance lies less in original innovation and more in serving as a cultural and historical artifact — a tangible, preserved testament to the rise of Playrix and the golden age of match-3, falling-block, and adventure puzzle games on PC between 2005 and 2010, long before mobile dominated the genre.

The pandemic-era resurgence of puzzle games and the current trend of remastered compilations (e.g., BioShock: Triple Pack) has made 2011 retrospectives newly relevant. Yet, unlike the interactive narratives or genre-redefining action titles often repackaged, the Playrix Triple Pack embodies a now-vitalized, yet once-ubiquitous format: the mid-tier, retail-distributed casual PC collection. It’s a relic of a pre-Free-to-Play (F2P) era, where physical game brackets existed for puzzle audiences, and Playrix was just one of several studios (like PopCap Games) thriving on this niche. This review aims to dissect each component of the bundle, explore the unique circumstances of their convergence, and argue that, collectively, these games — and their packaging — offer a remarkably clear lens into the late-2000s casual gaming ecosystem.

2. Development History & Context: Playrix’s Rise in the Casual Market Circus

The Studio: Playrix LLC – From Indie Upstart to Casual Powerhouse

Founded in 2004 in Ukraine by the Stepanov family, Playrix began during a paradigmatic shift in gaming: the casual game renaissance. As broadband adoption rose and non-gamers sought accessible, relaxing entertainment via downloadable PC titles (notably via portals like RealArcade, Big Fish Games, and Yahoo Games), a fertile ground existed for studios producing puzzle and time management games. Playrix emerged distinctively from this landscape not just by following trends, but by aggressively experimenting with genre hybridization and localized storytelling. Their early work was marked by “megadeals” for individual titles — buy three hours, get five. Their business model was simple: tight, addictive gameplay loops, frequent level progression, and a clear monetization path via unlimited play trials, time-limited demos, and full unlock purchases. By 2006–2008, they were already one of the top revenue-generating casual game studios in the world, as tracked by industry analysts like Sandvine and VMC Games.

The three games included here represent three pivotal years for the studio:

– Atlantis Quest (2006): Their breakout hit, merging match-3 puzzle mechanics with an adventure-quest narrative.

– The Rise of Atlantis (2007): A system-refined, more technically ambitious sequel, expanding scope, power-ups, and level complexity.

– Around the World in 80 Days (2008): A roadside standalone that transiently broke the ancient civilization theme, adapting Jules Verne’s novel into a falling-block and tile-mechanic hybrid.

This sequencing is critical. By 2011, these titles were not new — they were legacy flagship titles. The unusual delay between the individual games’ releases (2006–2008) and the compilation (2011) reflects Playrix’s growth and strategic shift. They had by then moved into mobile-first development, launching Gardenscapes (2011) and Homescapes (2017), which emphasized F2P, meta-class progression, and social interaction. The Triple Pack was less a new release than a nostalgia-driven, loss-leader catalog consolidation, designed to capture physical retail shelf space and introduce Playrix to newer, casual-game-averse demographics who might discover them via CD at a supermarket kiosk rather than on a PC download portal or mobile app.

2006–2008 Context: The Peak of PC Puzzle Gaming

The timing of the original games’ development was crucial. They were conceived in the golden age of the PC casual game, which boomed from 2003 to 2010. This era was defined by several factors:

– The “matching puzzle revolution” (Tetris, Bejeweled, Collapse!, Jewel Match) was mainstream.

– Adventures merged with puzzles (e.g., Runescape, Nancy Drew, Myst-lite hybrid games).

– CD-ROM remained viable — especially in countries with limited broadband (e.g., much of Eastern Europe, where Playrix was based, and the UK rural market, where the box targeted).

– Retail distribution was key — stores like GameStop, Zavvi, and even Tesco carried casual game packs.

Technologically, these games were built on the Adobe Flash/Flash Player browser engine, with some native Windows ports. They operated under significant constraints:

– Low target specs (Pentium III, 512MB RAM) to ensure accessibility.

– Fixed-screen, side-view perspective — no scrolling, 3D effects, or particle-heavy UI.

– 2D, static assets — hand-drawn, pre-rendered art, flipped between screens with minimal animation (just “flip-screen” transitions, not smooth camera).

– Point-and-click interface — fully mouse-controlled, no keyboard emphasis beyond menu navigation.

Notably, Playrix avoided the “hidden object” subniche (so prevalent among their peers, like Big Fish titles), focusing instead on pure logic and pattern-based puzzles. This purity allowed them to maintain player immersion without the fatigue of scanning cluttered scenes. The Triple Pack thus represents not just individual games, but a studio’s response to the technical, cultural, and commercial realities of 2006–2008 casual gaming, neatly preserved in a single box.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Grand Adventures in a Tiny UI Window

Core Narrative Anthologies: Time, Space, and One Lost Island

Each of the three titles in the Triple Pack constructs a narrative adventure around a core journey, but crucially, the story is always secondary to the puzzle flow. There are no cutscenes, voice acting, or real-time dialogue beyond non-playable character (NPC) speech bubbles and text overlays during travel/transition phases. The narrative operates as a thin veneer of stakes and context, justifying the player’s progression. Yet, within these limitations, Playrix demonstrates impressive restraint and clarity in worldbuilding.

Atlas Quest & The Rise of Atlantis: Myth as a Puzzle Metro Map

Atlantis Quest (2006) and its sequel, The Rise of Atlantis (2007), form a mytho-puzzle diptych set in a pan-Mediterranean ancient wonderland — a stylized, cohesive fiction blending Greco-Roman, Babylonian, Phoenician, and Egyptian iconography into a single continent-facing realm. The quest is the same: recover the lost power of Atlantis — the ultimate goal. But the narrative structure differs sharply.

Atlantis Quest is the entry-level mythologizing quest, featuring:

– A simple myth-to-mission progression: “First go to Egypt → find an artifact → solve a puzzle → next mission.”

– Travel via a 3D-rendered, rotating globe (one of the few visual luxuries) — selecting destinations.

– Minimal NPCs and story beats: Brief dialogue, comic-style speech bubbles, and environmental clues.

– Primary theme: Discovery — the joy of uncovering mysteries, inspired by Indiana Jones-esque quests.

– Underlying philosophical twist: Atlantis wasn’t hidden — it disappeared because humanity forgot its connection to Poseidon’s balance. The player, as the “chosen seeker,” restores cosmic equilibrium through puzzle-solving (a tidy metaphor for player-as-archaeologist).

The Rise of Atlantis, by contrast, is mythos as epic restoration. The story now unfolds through:

– A god-hero allegory: The player is a mortal reborn with the “favor of Poseidon,” tasked with reviving Atlantis as a divinely sanctioned project.

– Expanded travel mechanics: Instead of jumping, the player follows a sailing path across the map, unlocking cities in sequence (Greece → Troy → Phoenicia → Babylon → Egypt → Carthage → Rome). This is a gameplay narrative device, making the world feel contiguous, not fragmented.

– More robust NPC cult figures: Prophets, priests, and sages provide motivation and mild exposition.

– Theme: Rebirth through Order — the world collapsed into imbalance; puzzles are acts of rediscovering lost science/theology.

– Underlying political implication: Atlantis is the prototype of a theocratic utopia— a challenge to modern secularism, disguised as fantasy.

Both games rely on Myth as Puzzle Level-Up Token — the narrative justifies new mechanics. Solving a mummy’s riddle in Egypt unlocks a new power-up: the “Scarab Shield.” But crucially, Playrix avoids over-narrativizing. No moral dilemmas, no branching dialogue, no character arcs. These are not RPGs. The story exists to deliver context, tempo, and repeat Player motivation through a recognizable, myth-rich setting.

Around the World in 80 Days: Reimagining a Classic with a Puzzle Engine

This is the narrative outlier. While the other two are original fictions, Around the World (2008) retells Jules Verne’s 1873 novel through a puzzle metaphor. The core novel — a meticulously researched, global race against time — becomes a quest game with falling-block and tile-matching constraints.

- Verne’s novel is accurately adapted up to the level of geography: the same route from London to San Francisco via Suez, India, and America. But the obstacles are puzzle-based.

- Character roles are stripped to stock archetypes: Phileas Fogg (stoic, timepiece-obsessed Englishman), Passepartout (goofy, French servant who occasionally mutters in French).

- Narrative delivery via SMS-style dialogue — brief explanations from “newspaper updates” and telegraphs.

- Theme: Modernization as Progress — the game frames the 19th-century globe via technological novelty (airships, steamers, trains), with the player racing to align events with journal entries.

- Underlying irony: While Fogg seeks to win the wagger, the game structure ensures the player always wins — time is not a threat, just a progress tracker. The real challenge is completing each puzzle within a time/tile limit.

The genius of this retelling is its mechanical translation of Verne’s structure: the novel’s episodic, destination-driven format became puzzle level hubs, each requiring unique mechanics:

– Board-based matching puzzles (flying-cross mechanic) during “aerial” segments.

– Physics-based falling-block puzzles (like Collapse!) during train/ship navigation phases (e.g., navigating a lighthouse with blocks).

– Classic match-3 for recovery/recuperation phases.

This meta-narrative coherence — the idea that puzzle types match the mode of travel — is the genius of Around the World. It doesn’t replace the novel but offers a parallel experience: Verne as gamified.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Where Structure Becomes Ritual

Structural Breakdown: Core Loops, Progression, and Flow Control

Each game in the Triple Pack uses hybrid puzzle mechanics, blending several genres into a single, coherent system. They are not isolated match-3 or falling-block games but puzzle adventures with genre fusion.

1. Unified Progression System: Journey-Based Hubs

All three titles share a journey structure:

– World map or timeline interface where the player selects the next destination/level.

– Increasing difficulty curve through culture-based regions (past to myth/geography).

– Level-specific objectives, not just “clear 10 chains” — but “repair a fallen column in Babylon” or “disarm a capsule in an Egyptian temple.”

– Unlocks tied to levels, not passive accumulation — each city/country requires successful puzzle completion.

This creates a quest-like commitment level, unusual in casual games. Players aren’t just solving puzzles; they’re on a mission, which fosters engagement.

2. Core Puzzle Mechanics by Game

Atlantis Quest (2006):

– Primary system: Colored Tile Matching (Jewel Match style) with artifact piece collection.

– Mechanic: Like Jewel Quest, players match colored glyphs to reveal hidden images (artifact pieces) beneath. Completing a match fills a meter; when full, a piece of a sarcophagus, amulet, or sword is collected.

– Twist: Matching combinations reset the tile pool with new colored symbols, mimicking a “dig layer” for the artifact.

– Power-ups: Rare tools like the “Gold Grabber” (clears an area of tiles) or “Pulsar” (shuffles tiles).

– Innovation: No clocks or time limits in early levels — focuses on mastery, not pressure.

The Rise of Atlantis (2007):

– Evolved system: Falling Block Puzzle (Tetris-like), but with directional control and gravity — blocks fall, but players can rotate or nudge them like Lumines.

– Mechanic: Players stack or clear blocks to form Aqua-Board Channels — blue paths that activate mechanisms. Some blocks are movable, others fixed.

– Twist: Introduces three-layer depth — surface, mid-level (pipes), and underground (caverns). Each level requires channel paths across depths.

– Power-ups: “Wave Blast” (destroys a 3×3 area), “Poseidon’s Spear” (targets a specific block), “Time Warp” (slows block fall).

– Innovation: The hybrid of puzzle and light base-building — you’re not just solving; you’re restoring a civilization’s infrastructure. This is genre novelty.

Around the World in 80 Days (2008):

– Genre fusion: Match-3, Falling Block, Chain-Flash puzzles.

– Mechanic by phase:

– Match-3: For “calm navigation” (e.g., checking off a country on the itinerary).

– Falling Block: For “obstacle phases” (train wreck, ship explosion — clear blocks to escape).

– Grid-shift puzzles (like Super Escape Ball): For “transport dynamics” (align erratic cargo on a train).

– Twist: Phase-based flow — a single “day” (not part of 80 days) contains 2–3 puzzle types in sequence.

– Power-ups: “Fogg’s Watch” (freeze time), “Passepartout’s Luck” (shuffle tiles to create a match).

– Innovation: The real-time narrative sensor — puzzle completion updates Fogg’s travel journal, printed on the map.

3. UI, Flow, and Player Burden

- Minimalist, Function-first UI: All games use left-panel state tracking — destination completed, power-ups enabled, next puzzle type.

- No mouse-map: Players click on destinations, not explore the world like a sim.

- Pause and restart: Common, but no auto-save in-flight — leads to puzzle fatigue.

- Lack of multiplayer: All solo.

- No branching or side content: Linear — this is a curated, perfectionist experience, not an open-world.

- Fatal flaw in portability: The cd-only, single-account nature of the collection makes it non-save and hard to share — a modern weakness.

4. The Curse of “Addictive” Design: Reward Loops

All three games use variable ratio reinforcement schedules — unpredictable rewards (e.g., random power-up drops) to extend play time. However, they avoid pop-up ads (a mobile trope) and instead use:

– Level replayability: Completing a level with high score unlocks commentary, art, or time goals.

– Hidden objectives: “Clear 20 blue stones in 90 seconds” or “No power-ups for completion” — dark repetition.

– Local leaderboards: Yes, but not global — another relic of PC-era moderation.

This is not F2P addiction but PC casual engagement — designed for weeks or months of moderate daily play, not minute-to-minute bingeing.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: Myth, Magic, and Minimalism

Visual Direction: Pre-Rendered 2D with Thematic Symbolism

- Art style: 2D, hand-drawn assets, cribbed from early 2000s flash animation and print-on-demand history books.

- Set design: Each location (Babylon, Carthage, the British seaside) is stylized into retro-futuristic archaeology — imagine Terry Gilliam drawing National Geographic.

- Character sprites: Expressive, grotesque, comedic — Passepartout’s face moves with each dialogue, Phileas Fogg has a tiny, perfect beard.

- Ambient detail: Hieroglyphs on Egyptian tiles, Roman columns with crumbling capitals, Babylonian ziggurats with glowing runes.

The three games share a homemade, artschool aesthetic — clearly budget-limited but full of delicate symbolic care. The Atlantean temples aren’t digital renderings; they’re felt-board dioramas, inviting touch. The color palettes are cool for ice quests, warm for deserts — universal for tone delivery.

Audio Design: Minimal but Effective

- Original music: Orchestral, era-distorted tracks for each region:

- Egypt: jazz-age rag (fitting Verne) with pharaonic motifs.

- Atlantis: celesta and harp for dreamlike nostalgia.

- Greece: light woodwinds for pastoral peace.

- Sound effects: Clear, crisp, context-specific:

- ‘Clack’ for block falling, ‘tink’ for tile match, ‘shhh’ for sliding stone.

- No voice acting — only sound effects for dialogue ‘pop-in’.

- Volume sliders — very 2011.

The sound helps mask the repetitive gameplay. Each time you “solve” a puzzle, the game plays a unique audio fanfare — a micro-reward. This is sound as affective punctuation, not just score.

Atmosphere: Puzzles as Ritual

Together, these elements create an atmosphere not of urgency, but of ritual-like discovery. The world is not a place to conquer, but to understand through pattern recognition. Each puzzle session is like a visitor adjusting a museum exhibit — focused, deliberate, and self-contained. The presence of historical and mythical themes enhances this feeling — you are, in a sense, re-enacting a story of civilization through mechanics.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Forgotten Titan of Puzzle Design

Original & Compilation Reception

- Individual games (2006–2008): Critically positive among casual game reviewers (e.g., Gamezebo, ProFantasy) with scores averaging 4.2/5. Praise for creativity, pacing, and thematic integration. Sales figures are murky, but Playrix reportedly earned tens of millions monthly by 2009.

- 2011 Compilation: No critical review (zero on Metacritic, MobyGames, or GameSpot). This silence is telling. It wasn’t new, and it wasn’t revolutionary. It was a “value package”. The only audience was retail puzzle enthusiasts, not digital-first critics.

- Commercial performance: Unknown exact figures, but the fact that it received only one collector entry on MobyGames — entered in 2024 — suggests limited print run and shelf life. The Triple Pack quietly disappeared from stores by 2013.

Legacy and Influence

While obscured, Playrix’s impact is incalculable:

– Bridge to mobile: Homescapes (2017) evolved from Atlantis Quest‘s treasure-collecting and world-restoration loops.

– Genre hybridization: The way Around the World merged travel narratives with puzzle types influenced Monument Valley (2014) and Alba: A Wildlife Adventure (2020).

– Non-object, narrative puzzles: Their avoidance of “hidden object” clutter made puzzle storytelling accessible beyond niche audiences.

– Soviet-bloc game design: Playrix, like King (Sweden) and Zynga (USA), was a major studio built outside the US-UK AAA corridor — proof that casual excellence could rise from peripheries.

The Triple Pack also influenced indie bundle culture — it was one of the first “quality curation” pc casual collections, not just a “three cheap games for $9.99” dumps. Unlike Zoombinis or Super C, it had thematic unity.

Today, the collection is a lost artifact, sought only by collectors and historians. But within it is a future blueprint — the seeds of F2P, meta-game management, and emotional narrative puzzles now everywhere in Candy Crush, Wordscapes, and Pogo.

7. Conclusion: A Time Capsule for the Casual Age

The Playrix Triple Pack (2011) is neither a masterpiece nor a failure. It is a historical novel bound in a game box — a tangible, preserved specimen of a pivotal moment in gaming culture. It captures the last gasp of retail PC casual games, the commercial apex of download-to-buy puzzle adventures, and the artistic maturity of Playrix LLC before their ascension to mobile empire.

What makes it significant isn’t its originality — none of the mechanics here are new — but its curation, context, and cohesion. The three games, released over three years, are not redundant but complementary: a scholar’s guide to a genre in transition. They show how a studio can merge narrative, myth, puzzle type, and cultural aesthetics into a repetitive, hypnotic, yet meaning-rich experience.

Its flaws — desktop-only UI, linear progression, CD-only portability — are now strengths: they preserve the aesthetic and function of a pre-iPhone, pre-tablet world where games came in cases, ran on low specs, and were played at night after work.

In a 2025 gaming landscape dominated by live-service F2P and complex narratives, the Playrix Triple Pack stands as a quiet monument: not to revolution, but to revival — the revival of forgotten forms, reverence for simple pleasures, and the enduring appeal of a well-designed puzzle.

Final Verdict: ★★★★☆ (4 out of 5 stars)

The Playrix Triple Pack is not just a collection. It is a cultural text, a museum of mid-2000s casual design, and a testament to the power of niche excellence. For game historians, it’s essential. For puzzle fans, it’s nostalgic. For the industry, it’s a warning: what thrives in one era can vanish in the next — but if preserved, it can still teach us how to play.