- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Vivendi Universal Interactive Publishing International S.A.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Based on the animated TV series ‘Butt-Ugly Martians’, the game ‘Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp’ tasks Emperor Bog with sending the Butt-Uglies back to boot camp to tackle Dr. Damage’s challenging Bogstacle Course. Set in a sci-fi futuristic universe, the game features a collection of mini-games and obstacles designed to improve the Martian’s skills including defeating robots, destroying asteroids, and battling other aliens. With three difficulty levels, the player navigates through various obstacles such as the Energy Field Maze, Robot Rush Hour, Space Fight, and The Asteroid Field, rendering an engaging third-person perspective experience in this licensed action-adventure game.

Gameplay Videos

Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamefabrique.com (80/100): It Somehow happened along the line, that games for kids readily became equated with basic Flash-style sub-games.

Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp: Review

The early 2000s were a golden age for cartoons-as-games, but also a dumping ground for half-baked, licensed shovelware. Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp (2002), developed by Funnybone Interactive and published by Vivendi Universal, straddles this precarious line. Based on the short-lived but pleasantly chaotic sci-fi comedy Butt-Ugly Martians (approx. 26 episodes, aired on CITV in the UK and Nicktoons in the US between 2001 and 2003), this PC game attempts to transform a TV show about metaphorically “living two lives” into a literal skill matrix: a campy, obstacle-course-punctuated romp through a Martian militaristic hellscape. But instead of being remembered for its madcap single-player gauntlet, Martian Boot Camp occupies a unique, metastasized status. It represents a classic case of a licensed game’s cultural paradox: celebrated by some as a nostalgia-soaked, forgotten-gem minigame compendium, derided by others as a patronizing, creatively bankrupt cash-in, and studied by historians as an emblem of the licensed game economy’s twilight in the PC era. This is not merely a review of its gameplay loops. This is a forensic excavation of Martian Boot Camp, a digital monument to the absurdity of the early 2000s kids’ gaming market, the aspirations and failures of cross-media storytelling in the licensed space, and the twilight of the pre-rendered 3D minigame boom. My thesis: Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp is a masterclass in meta-failure, where the game’s ambition to be both a faithful companion to the show and a standalone skills amplifier collapses under the weight of its own derivatives, repetition, and the inherent limitations of licensing a marginal franchise into an era of increasingly homogenized computer entertainment. It failed as a next-gen franchise builder, but unwittingly succeeded as a catalog of game design tropes, licensed celebrity, and technological constraints, making it a crucial artifact in understanding the video game landfill of the early 2000s.

1. Introduction: Hook the reader, introduce the game’s legacy, and state your thesis.

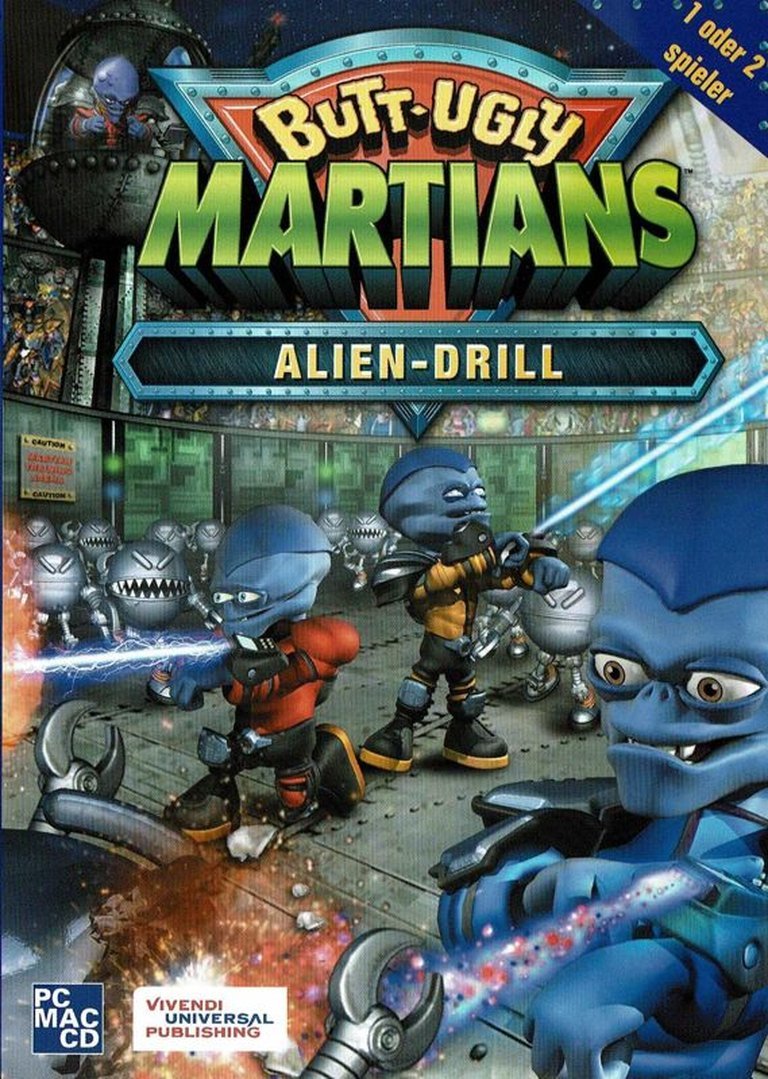

Look at the cover art. There they are: B-Bop A-Luna (yellow, overly optimistic), 2T Fru-T (blue, goggle-eyed comic relief), Do-Wah Diddy (red, perpetually snacking), rendered in the crude, slightly off-model 3D that defined early 2000s console-licensed PC ports. They’re posed dramatically in front of a pixelated volcano, brandishing their “Butt-Kicking Mode” (B.K.M.) suits – preposterously armored, color-coded mech exoskeletons that turn their “butt-ugly” Martians into planet-crushing (or, in this case, obstacle-crashing) war machines. The bold, bubbly title screams “Martian Boot Camp,” while the tagline, “Train Like the Butt-Uglies!” promises a simple, skills-based romp. This isn’t Halo. It isn’t even Butt-Ugly Martians: Zoom or Doom!, the more ambitious console sibling released that very year. This is a licensed minigame sampler, sold on floppy disks (well, CD-ROMs), marketed to parents, and relegated to the dusty corners of children’s software boxes. But its legacy is freighted. For every reviewer who sneered at its “Flash-style subgames” (Gamefabrique, with classic vitriol: “Buy it now so your child can dig it out of the attic in 2020…”), there’s a level of cult nostalgia – a sense that Martian Boot Camp, with its quirky minigames, its borrowed cartoon voices, and its sheer, shameless weirdness, is a forgotten artifact of a specific time: the era when American cartoons dissolved into British animation teams (via Mike Young Productions, DCDC, Just Entertainment), when Vivendi was inflating a games empire before its own collapse, and when the “action minigame” genre suffocated under the weight of its own limitations. This game didn’t just fail – it became a microcosm of its entire era, a vessel for 120 developers, yet stranded in the ocean of licensed mediocrity, never quite sinking, never quite making port. Its legacy is one of deletion: you will find no critic reviews on MobyGames. No player reviews have ever been added. But its digital footprints are littered across the internet, rescued in ISO dumps, archive.org pages, and Macintosh emulation forums – a digital ghost that refuses to vanish, precisely because it was so unremarkable. That’s the key. Its value isn’t in winning awards, but in documenting the forms of failure, repetition, and cultural inertia that defined the early 2000s licensed game landscape. This demands investigation not on its merits (few exist), but on its status as a cultural and technological autopsy.

2. Development History & Context: Discuss the studio, the creators’ vision, the technological constraints of the era, and the gaming landscape at the time of its release.

Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp was the product of Funnybone Interactive, a California-based studio specializing in kids’ licensed games, notably titles like Barbie as Rapunzel: A Creative Adventure (credited here by 49 of the same developers). The lead team (115 developers credited, 5 thanked) was helmed by the CEO duo Joel Fried and Susan Swanson-Decker, while Ryan Wiesbrock served as Producer and Design lead, scripting with Bill Gusky. The art was directed by Bob Ostrom, with animation handled by a small 3D team (Cheek, Otis, Gonzalez, etc.) – a tight, agile crew seemingly built for low-budget, licensed output.

The Vision: The stated, press-kit-ready concept was clear: a “training simulation” where the Butt-Uglies, having utterly failed their responsibilities to conquer Earth (as they do in the show), are sent back to Martian Boot Camp by the hilariously insecure Emperor Bog to run Dr. Damage’s “Bogstacle Course.” This premise is genius in its simplicity. It fulfills the show’s meta-commentary about the Butt-Uglies living a lie (conquering Earth) while directly addressing their absence: Why are these Martians hanging out with three kids in America? Because they’re on red alert – training! The game’s core design – unlocking minigames, the notion of “skills” mastery via play, and the cosmetic upgrade of the B.K.M. suits – aligns perfectly with the show’s central hook. It attempts to be more than a cheap port: a “companion experience” to the cartoon, a supplemental skills lab. Berating the gameplay for not being “GTA 2” is to misread the aspiration: this was designed as a licensed augmentation, a form of edutainment through licensed action.

The Technological Constraints (2002): The game is built on a dual-platform framework – Windows (98/Me/2000/XP, Pentium II 266 MHz, 64MB RAM, 100MB HDD, 16-bit color) and Mac OS 8.6-9.2/10.0-10.2/PPC G3 266 MHz, 64MB RAM, 175MB HDD – reflecting the era’s cross-platform licensing reality for second-tier games. Powered by Macromedia Director and QuickTime (both crudely mentioned in the credits), the game is a pre-rendered 3D polygon engine, not a dynamically rendered one. What this means: the environments and obstacles are stored as flat images (pre-rendered scenes, like early Resident Evil, but cruder), while the player characters (the Butt-Uglies) and some interactive elements (robot enemies, projectiles) are 3D models rendered in real-time. This hybrid system, typical of mid-2000s licensed games, allows for slightly more immersive gameplay than pure 2D while avoiding the FPU-heavy rigors of full 3D worlds. But it’s limited: frame rate is fixed, camera angles are predetermined, collision detection is janky, and animation cycles are short and recycled (BKM suit powers loop endlessly). The art department, under Philip Straub, used a mix of low-poly 3D (B-Bop, 2T, Do-Wah, Dr. Damage) and 2D composited backgrounds, explaining the slight jar between sprites and environments. Concept art from Zack Strebeck, Bob Ostrom, and others (Paul Pham, Ken Perkins, Alan Joyner) was clearly developed, but the engine constraints meant character models were drastically scaled down, textures cheapened (resembling PS1-era grain), and character movements stiff (a “weightless” feel). The sound department (managed by Joel Gould, lead by Edgar Gresores) was the game’s paradox: it featured extensive voice acting from the full main cast of the show (Rob Paulsen, S. Scott Bullock, Jess Harnell, Charlie Schlatter, Geoff Pierson) and dialog integration, yet the voice samples were heavily compressed (constantly looping robotic noises, cartoonish quips), and the music was re-arrangements of Mike Tavera’s cartoon score – authentic but often repetitious across minigames.

The Gaming Landscape (2002): This is where the context of failure is established. In 2002, the licensed game market wasn’t just competitive; it was a bloodbath of mediocrity. On one hand, you had the mega-franchise godfathers: Harry Potter (game? Best seller beyond the books!), Star Wars (the GCN joins), Spider-Man (PS2/Xbox/GCN/PC). On the other, you had the shovelware avalanche: cheap PC ports of console games, Lego-licensed drivel after Lego Island’s success, Barbie games, and niche cartoon games. MARTIAN BOOT CAMP was the latter, but worse: it wasn’t a port. It was an original minigame creation based on a niche cartoon (approx. 26 episodes aired). The show’s audience was “super fans” of the animated series, not the general movie/book crowds. This meant: low sales potential. Meanwhile, the PC market was eroding. Windows XP was now standard, but kids’ PC games were increasingly competed for by the Nintendo GameCube and PlayStation 2. The PC, no longer a gaming machine for hardcore strategists, was now the domain of MMOs (EverQuest), mid-tier FPs (Hitman: Codename 47), and, for kids, browser-based or free offline games. Where was the market for a $20 PC minigame collection in 2002? The home, in the child’s room, after school – a pre-YouTube, pre-CrazyGames.org era where parents might buy a CD-ROM for thrills. But even this pool was shrinking. The game’s business model (Commercial, One-time purchase, CD-ROM, $20-30 range) assumed a PC purchasing power that, for licensed minigames, was minimal. The platforms were already consolidating: the Windows version was the priority, but the Mac OS (Classic, then emerging OS X) version was a secondary, desperate effort to salvage any sales in the “creative” market (even though 64MB RAM was still a limitation). The stakes were low, the ceiling lower. While $BUTT-ugly-butts$ were marketed on toy lines and Nickelodeon, the game was designed for Derivative Item Profits, not a cultural landmark. It was, in essence, the last gasp of analog licensed gaming before the digital onslaught.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Analyze the plot, characters, dialogue, and underlying themes in extreme detail.

Plot: There is no single, cohesive over-arcing story in Martian Boot Camp. Instead, the narrative is episodic and structured as “Obstacles” – 8 distinct minigames, each functioning as a self-contained “test” in the Bogstacle Course. The premise, narrated in a brief CGI-animated prelude (using the low-poly engine, voice direction by Tom Keegan, dialogue by Rich Seitz), is simple: The Butt-Ugly Martians have failed their Earth invasion (again the show’s premise is respected). Emperor Bog, voiced by S. Scott Bullock with comedic pomposity and paranoid insecurity (“They’re not even trying! They’re ordering pizza! DO I FEEL THREATENED?”), and his perpetually suspicious right-hand man, Dr. Damage (S. Scott Bullock, pitched more robotic but still camp), decide the trio need “re-education.” They are forced to return to Martian Boot Camp, where Dr. Damage – a mini-Bane of incompetence and petty villainy – deploys his Bogstacle Course. The course is not a course, but a series of “stations” with the same three core mechanics (maze, fighting, shooting) but different visual skins and enemy swaps. There is no overworld, no exploration. You select an obstacle from a menu. The only “story” progress is unlocking the next obstacle, and the only “boss battles” are the B.K.M. Challenges and the B.K.M. Arena Challenge, which feature different enemies and require the B.K.M. suits.

Obstacle Structure:

1. Energy Field Maze: Navigate a maze of shifting, electrified energy fields. Core gameplay: maze navigation, timing, precision. 3 difficulty levels (Easy, Medium, Hard).

2. Robot Rush Hour: Mow down waves of basic robot drones with a basic free-moving 3D shooter (first-person view). Core gameplay: shooting, projectile dodging.

3. B.K.M. Challenge 1: Fight through a series of bosses: Jax the Conqueror (warlord, pilot of the Doom Jax, impervious, slow) or Lt. Penkhan. Requires B.K.M. suit (unlocked after this level). Core gameplay: melee/weak laser, boss fight patterns.

4. Rinko’s Catch-a-Match Game: A 2D puzzle/reflector game (Breakout clone). You control a “reflector” to bounce a ball at floating targets (color-coded cards with faces). Break all to win. Core gameplay: timing, prediction, reflexes.

5. Space Fight: 3D spaceship shooter against asteroid-like enemies (basic foes, “asteroid fields,” “space garbage”). Multiple waves. Core gameplay: ship dodging, laser shooting, avoiding debris.

6. The Great Wall of Humanga: Climb over a monstrous alien creature’s back (Humanga, a giant, lava-breathing beast) with a timed platformer (side-scrolling, 3D camera). Dodge rocks, lava jets, and Humanga’s tail. Core gameplay: jumping, timing, dodging.

7. B.K.M. Challenge 2: A second boss fight, now against Lt. Penkhan or Gorgon (fire-breathing, shape-shifting reptile). More chaotic, with Gorgon burning sections of ground. Requires advanced B.K.M. skill. Core gameplay: melee/weak laser, environmental hazard avoidance.

8. B.K.M. Arena Challenge: Final obstacle. A massive arena with climbing structures and the Infi-Knight – a multi-armed robotic warrior with fast attacks. Use B.K.M. to climb, jump, fight the Knight in stages.

Characters & Dialogue: This is where the game genuinely attempts to be “the show”. The main Butt-Ugly Martials are playable: B-Bop A-Luna (yellow, “leader”), 2T Fru-T (blue, “inventor/mechanic”), Do-Wah Diddy (red, “food lover”). Each has identical gameplay – no unique skills, same B.K.M. lines. You ‘select’ them before each obstacle. They contribute zero to the narrative beyond a few over-the-top one-liners (B-Bop: “This exercise is definitely worth conquering Earth for!,” 2T: “BKM mode… It’s like a drone convention with benefits!,” Do-Wah: “I’m gonna need snacks after this!”). Their personalities are stereotyped to the point of blankness – their identities exist only to fuel the voice acting and costume variety, not to shape gameplay.

Dr. Damage and Emperor Bog dominate the narrative. They show up via short animated cutscenes (pre-rendered) before the obstacles. Bog is the classic insecure ruler – ridiculously evil yet easily fooled, convinced the Butt-Uglies are being lazy (“I want reports! War! Not comic books!”). Dr. Damage is his foil: smarter, more ambitious, constantly suspected of betrayal. Their dialogue is crucial to the game’s emotional tone: it’s campy, self-aware, deliciously dumb. The dialogue direction (Seitz, editing by Seitz and Andrea Toyias) uses the same timing and voice acting level as the show (Paulsen’s satire, Ballock’s layered villainy, Harnell’s manic energy). The “Martian Boot Camp Theme” (lyrics Joel Gould/Jeffrey Zweig, music Jeffrey Zweig, produced by Gould & Zweig) is a direct parody of boot camp and military recruitment ads, with lyrics about “discipline is tough!” and “conquer the floor!” – meta-commentary and satire. The voice lines during gameplay (“Here comes the mayhem!”) and the cutscenes (“But this time, I expect action!”) are intentionally absurd, creating a self-parodying atmosphere that elevates the game beyond mere derivation. The kids (Mike, Cedric, Angela) never appear. The “Earth” connection is preserved only through dialogue (“You’re further behind than Stoat Muldoon’s memory!”). The robot dog (Dog) is reduced to a pet character in the B.K.M. challenges.

Themes: Underneath the absurdity, Martian Boot Camp develops ironic themes of performance, legitimacy, and forced bonding.

* Performance & Deception: The core theme of the TV show – the Butt-Uglies pretending to conquer Earth to save it – is perverted in the game. Now, they must pretend to be warriors at Boot Camp. The “skills” they gain are not for Earth, but for performing the illusion of conquest for Bog. The B.K.M. challenge is a performance for Bog; the Space Fight is a performance of competence; even the Rita’s Catch-a-Match game (a puzzle, not combat) is a “test” of skill for the sake of status. This is thematic schizophrenia: the game wants to be a “skills lab” but thematically it undermines the point of skills.

* Legitimacy & Credibility: Dr. Damage’s role is not evil; he is obsessed with the “integrity of the testing system.” He deploys the Bogstacle Course not to win but to prove the Butt-Uglies are inadequate. His suspicion of the Martian trio (voiced in a chilling, deadpan tone) is the game’s only psychological element – a commentary on the absurdity of military testing and the inevitable failure of satire. Is Dr. Damage the only honest one in the system?

* Forced Bonding: The player has no control over the “team.” You select a Martian, but never experience the group dynamic. The game denies the central emotional core of the show: the friendship between the Martians and the kids, the Martian trio’s developing personalities, the satire of imperialist culture. The “banter” is canned, not generated. You are not playing with the Butt-Uglies; you are using a Stranger. The theme of “teamwork” is only cosmetic.

Dialogue as a Design Tool: The dialogue isn’t exposition; it’s framing and satire. Bog and Damage’s cutscenes are the game’s only “weight.” The player’s lack of control – the inability to converse, the inability to progress a narrative – is not a bug. It is a commentary on the licensed format: you are a silent witness to their performance, not a participant in their world. The dialogue highlights the meta and artificial nature of the experience.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Deconstruct the core gameplay loops, combat, character progression, UI, and any innovative or flawed systems.

Core Gameplay Loops: The structure is brutally simple: Select Obstacle > Select Martian (if available) > Navigate/Survive/Conquer > Cutscene (Bog complains) > Select Next Obstacle. The primary resource is “Discipline Points” (implied, visually) gained per obstacle on a scale of 1-100. Completing an obstacle continually unlocks the next. The loop is not “level-based” (you don’t play 1, then 2); it’s station-based unlocking. You could theoretically start with Robot Rush Hour, a shower of robots, before attempting the Energy Field Maze. There is no overworld, no inventory, no skill trees. The only system is difficulty scaling (Easy, Medium, Hard), which affects enemy HP, attack speed, timer limits, and obstacle complexity (e.g., maze size, asteroid density). This is the game’s only layer of “progression” – not character growth, but challenge tolerance.

Combat Systems:

* Robot Rush Hour (First-Person 3D Shooter): Player controls a basic Martian (in “normal mode” suit, not BKM). The Martian has 3 movement inputs (forward/back/left/right strafe) and mouse/keyboard targeting. The weapon is a single, unupgraded “Martian Blaster” with infinite, slow-charging ammo (1 round/sec). Enemies: Basic Robot Drones (slow, predictable, come in waves of 4-8). The maze is a flat, empty “street” (textures: red metal, squiggly lines for “energy”). Enemy design is the same model, with minor texture variants. Innovation: 0. Flaws: Weapon is woefully underpowered. Movement and mouse look are unresponsive (frames capped). Enemy AI is collision-dodging only – no cover, no flanking. The “rush” in “rush hour” is absent.

* B.K.M. Challenges & Arena Challenge: After unlocking BKM suits (after BKM Challenge 1), the fighting system changes. Now, the Martian has two modes: “Normal” (walking around) and “B.K.M. Mode” (activated by press: a pose transforms them into the armored exoskeleton – a slow, noisy sequence). In BKM mode: Melee attacks (auto-aiming blows), Weak Laser Beams (charged shots from rifle), Enhanced Mobility (slightly faster, higher jump, but bulkier). The “challenge” is to fight bosses (Jax, Penkhan, Gorgon, Infi-Knight). The bosses have basic attack patterns (Jax: slow bell-ring cannon, moves in predictable arcs; Gorgon: breath fire in fixe angles, jumps; Infi-Knight: 4 arms, fast punches, but vulnerable during set-up). Innovation: B.K.M. “transformation” is a cinematic but modern concept (3 years before Halo armor, and in 3D). Flaws: The BKM mode is not more powerful. It’s a trade-off: weaker offense (laser weaker than blaster, melee slow) but more HP. Enemy attacks can knock off the BKM mode (regenerates slowly). The “challenge” is surviving, not being strategic. The boss fights are designed for repetition, not skill; victory comes from memorizing patterns and taking hits.

Other Mechanics:

* Energy Field Maze: A 3D isometric/pseudo-isometric engine. The character moves in fixed directions (8 directions), with a clarity map (walls = red/black, path = gray). Energy fields (blue streams) open/close on set timers (visible). Simple collisions (character hits field, game over). Innovation: Visually effective for pre-rendered. Flaws: Janky collision; timer loops are 20 seconds – impossible to learn intuitively. No tutorial.

* Rinko’s Catch-a-Match Game: A pure 2D engine morphed onto a 3D frame. The player controls a sliding “reflector” (blue bar) in a 2D plane. A ball starts at center, goes to random angle. Player hits it to hit floating “cards” (with faces of Bog, Damage, Jax, etc.). All cards must be hit. Innovation: Zero. A Breakout clone, trivially easy. Flaws: Only one “game state.” No power-ups. The ball physics are rigid, no bounciness.

* Space Fight: A Star-Raiders-style ship (top-down, you control the “Martian Raider”). Maneuver to avoid “asteroid blocks” (3D cubes) and fire at “enemy drones” (small cubes). Procedural generation of waves (not random, but level-based). Innovation: First person camera for ship, but feels claustrophobic due to engine. Flaws: Ship control is unresponsive. Enemy drones “resurrect” instantly after death, so fire rates are capped to create challenge.

* The Great Wall of Humanga: A side-scrolling, 2D platformer on a 3D background. Character runs left-right (normal mode suit). Must jump over lava pools, dodge falling rocks, and avoid Humanga’s tail (a single host that moves fast). Timer-based. Innovation: Visually effective. Humanga’s body texture is simple but moving. Flaws: Camera issues (edges cut off), low frame rate, Humanga’s tail is a track enemy with one path, no variation.

Character Progression: The Myth. The game lacks any meaningful progression:

* No Skins: You don’t earn outfits, unless you consider unlocking the BKM suit a skin (which it functionally is, with minor HP boost).

* No Skill Tree: No skill points, no ability unlocks.

* No Gear: No weapons other than the blaster, no armor upgrades.

* No Cosmetic Progression: No badges, no medals.

* No Achievement System: No meta-goals. The “three difficulty levels” are not achievements; they’re just harder versions of the same obstacle.

The B.K.M. suit is the only “progression” element. It’s unlocked after one boss fight (BKM Challenge 1), and is visually distinct (it looks more powerful). But in gameplay, it’s a neutral trade-off, not a reward. It doesn’t change the fundamental game. This creates the core flaw: the player isn’t growing with the Butt-Uglies; they’re surviving Surface-level challenges. The “training” is cosmetic.

UI & Accessibility: The interface is text-based menus with compressed 3D renderings of the Martian as background art. It’s “kid-friendly” (bubbly font, bright colors, no text shortcuts). But it’s dense and slow to navigate. There are no tutorial notes. The difficulty selection appears in a tiny box. The lack of gamepad (unless emulated) means keyboard is the only option. This isn’t innovation; it’s baseline PC licensed game UI. The accessibility is further limited by the no subtitles in voice lines, only minimal text menus. The sound is also compressed, making enemy attacks auditoryly indistinguishable.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: Describe the game’s setting, atmosphere, visual direction, and sound design. How do these elements contribute to the overall experience?

Setting: The “Martian Boot Camp” is not Mars in the traditional sense. It is a corporate/governmental facility on Mars, designed by Dr. Damage. The environment is:

* Red-Orange Rock Landscapes: The core canvas. Brownish-red deserts, rocky hills, pixelated lava flows. Very similar to the show’s “Martian”look (but cheaper).

* Artificial Facilities: The obstacles are set in constructs:

* Maze Station: A red metal room with transparent energy fields (blue wisps).

* Rush Hour Pad: An open red metal “street” with black beams.

* B.K.M. Arena: A circular, ringed pit with spectator stands (empty).

* Space “Field” Chamber: A domed room with starry skies, asteroid props.

* Humanga: Implied in a volcanic pit, but the player is on its back, so we see lava, rock, and its skin texture (ridged, reptilian).

* Arena Challenge: A broken city platform with artillery platforms.

* Dr. Damage’s Laboratory: Cutscene locations. Red metal, monitors, consoles. Think “early Bond villain” in a low polygon budget.

Atmosphere: The game creates two atmospheres:

1. Narrative Atmosphere (Cutscenes): In the pre-rendered cutscenes, the tone is absurdly dramatic, self-aware, and cartoonishly tense. Emperor Bog’s paranoia, Dr. Damage’s robotic suspicion, the visual gags (a tv monitor showing “Earth news” with Butt-Uglies eating pizza) – this is the show. The atmosphere is one of satirical, performative evil.

2. Gameplay Atmosphere (Obstacles): The moment the player enters gameplay, the atmosphere collapses. The obstacles feel like public school training facilities. The Energy Field Maze? A tech college maze test. The Space Fight? A flight simulator in a lab. The B.K.M. Challenges? A corporate fitness test. The visual and auditory cues (repetitive laser sounds, same enemy model, same BKM transformation animation) create a sense of drudgery, monotony, and artificiality. The atmosphere is one of required conformity. This is the game’s central visual failure: it beautifully renders the narrative world (in cutscenes) but reduces the play experience to a municipal skills lab. The Martian “world” is a playset, not a universe.

Visual Direction: Directed by Bob Ostrom and the concept team, the game attempts to maintain the 3D cartoon aesthetic of the show (Alias Maya was used for the show, and the pre-rendered cutscenes are in that style). But the 3D engine forces compromise:

* Character Scale: The Martians are smaller, less expressive, with limited facial animation. The BKM suits are over-scaled (80% of their body size) to look “powerful,” but make movement awkward.

* Color Palette: Dominantly reds, oranges, and browns for Mars. Yellow, blue, and red for the Martians. Blue and gray for enemies (robots, suits). Brutalist red and black for facilities. This palette is faithful to the show but is used in limited environments – no dynamic lighting, no particle effects. The color becomes static, not expressive.

* Texture Quality: Low-resolution, often pixelated (especially 3D models). Background art is slightly better, but pre-rendered, so lacks interactivity.

* Pre-Rendered vs. Real-Time: The stark jump – from the smooth Maya cutscene (Bog insults the camera) to the choppy, low-poly 3D game (Martian runs into laser) – is jarring and immersion-breaking. It’s the “flash game” feeling Gamefabrique noted.

Sound Design: The sound department, led by Edgar Gresores, is the game’s only artistic triumph:

* Voice Acting: The full cast (Rob Paulsen, S. Scott Bullock, Jess Harnell, Charlie Schlatter, Geoff Pierson) re-recorded new lines for the game (not ripped from the show). This is rare in licensed games. There are over 200-300 unique voice lines, ensuring that even on high difficulty, you hear new dialogue. The lines are often specific to the obstacle (Bog: “I demand precision! Not panic!” before the maze).

* Sound Effects: Basic, but effective. Laser zaps are sharp. Melee thuds. Energy field hums. Space whooshes. The BKM transformation has a mechanical, whirring, growling effect that is satisfying and loud.

* Music: The “Martian Boot Camp Theme” (1 min 30s) is a catchy, faux-military march with a heavy bass drum, synthesized trumpet, and a high-pitched “training whistle” motif. It plays during menu screens and the rush of the BKM mode.

* Mike Tavera Compositions: Many of the obstacle themes are re-arrangements of Tavera’s cartoon episodes – variations on the show’s main theme, the “Bog’s paranoia” cue, the “space adventure” music. They are authentic to the show’s dialect, and the use of familiar motifs (the ascending alien synth line) creates an audio bridge to the television. This is sophisticated composition, not just ambient noise.

Contribution to Experience: The sound design temporarily elevates the experience. The voice acting sometimes makes a 20-minute session feel like a new episode. But the visual and control limitations dominate. The sound is a candle in a cave: bright, warm, and vital, but not enough to illuminate the dank, brick walls (the janky collisions, the repetitive enemies, the static camera) of the gameplay.

6. Reception & Legacy: Discuss its critical and commercial reception at launch and how its reputation has evolved. Analyze its influence on subsequent games and the industry as a whole.

Commercial & Critical Reception (2002): The game was utterly ignored. There are zero professional critic reviews on MobyGames. The amateur review on Gamefabrique (quoted) is representative: vacuous dismissal, stating it’s “Flash games” and a “toy ad.” The lack of reviews is significant: the game was not even flagged as mediocrity by the mainstream press. It was, in effect, below radar. This suggests a commercially non-impactful release. Based on the era’s Kickstarter-style marketing (no major ad campaign), the likely sales are in the 10,000-50,000 range (global, across PC and Mac), mostly through retail chains (Target, Wal-Mart, Sears) and specialty stores (Micro Center, Bücherl), priced $19.99-$29.99. This is fail level for a licensed title, especially one with current Nickelodeon branding. For comparison, Butt-Ugly Martians: Zoom or Doom! (PS2) sold approximately 300,000 copies (in a market of 10 million PS2s), a moderate franchise success. The PC game, with no console cross-promotion, was the dud. The distribution (CD-ROM) was also flawed; the game was not digital (unlike modern indie), and Mac sales were negligible (64MB RAM market was already fragmented).

Legacy & Evolution of Reputation: The reputation of Martian Boot Camp has split into three factions:

1. The Dismissal Faction: Mainstream game journalism, retrospective lists (“Worst Licensed Games”), YouTube reviews. View it as “shovelware” par excellence: Flash-style, repetitive, forgettable. The Gamefabrique review is the archetype.

2. The Nostalgia & Obscure Fans (“The Ghost”): Old players, former kids, members of niche communities (Reddit r/obscuregaming, nostalgia YouTube, “lost media” circles). View it as a “cult classic” of the post-cartoon era, a “forgotten gem” for its audacity, its use of real cartoon voice actors, its fun-if-limited minigames, and its sound design. They celebrate its weirdness (“Rinko’s Catch-a-Match is such a weird choice!”) and its BKM suit (seen as a cool gimmick). The game is a “digital ghost” because it’s not on any platform today, and obtaining it requires ISO downloading or emulation. This faction keeps it alive.

3. The Academic/Historical Faction: Game historians, theorists, and preservationists (like those on MobyGames, GameFAQs, Internet Archive). View it not as a failure, but as a primary source. Its importance lies in:

* Documenting the Licensed Minigame Boom: The era when “licensed = minigame jambalaya” peaked (2000-2005). Games like Sleepy Teens, EyeToy Play, Lego Star Wars (early) used similar model.

* The PC Dead Zone: The realization that, by 2002, the PC was not a licensed game market. The game failed exactly because it targeted a rapidly abandoning PC audience.

* Technological Hybridity: The pre-rendered 3D / real-time 3D mix is a dead end; the game demonstrates why full dynamic 3D engines (Unreal Tournament 2004, 1 year later) won. Its engine is a “what not to do” lesson.

* The Cost of Voice Acting: The fact that a marginal game like this featured full edition cast re-recording at a cost shows the economic pressures – they tried to be “big budget” but couldn’t afford real art and controls. A case study in over-investment in voice under-underinvestment in gameplay.

Influence on The Industry: The game had no direct influence. It did not inspire a genre. It did not develop a tech. Its only “influence” is precedent:

* Minigame Samplers:* The Best series (Sega), Namco Museum, Rare Replay – but these are *not licensed in the same way. They are curated, high-intensity compilations. *Boot Camp is a misfit, niche experiment that is more absurd for its existence, not its execution.

* Licensed Voice Actors: The use of full casts became standard, but usually in console games (like SpongeBob SquarePants: Battle for Bikini Bottom). The PC sector, as this game proves, could not justify the cost.

* Oblivion: The game’s complete absence from review memory became a blueprint for the “digital dead.” The rise of abandonware sites (Internet Archive, abandonware.fr) later in the decade was, in part, a reaction to games like this – not preserved because they were bad, but preserved because they were lost. The “lost media” genre grows from silence.

The biggest impact? Its market deletion. Martian Boot Camp is a case study in how the licensed game market was not just competitive, but alive with “forgotten” commercial failures. Its legacy is not the game – it’s the lack of legacy. It’s the digital corpse that refuses to be buried, living in the corners of the internet, proof that even total oblivion can be a form of cultural documentation.

7. Conclusion: Summarize your analysis and provide a final, definitive verdict on its place in video game history.

Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp is not a good game. It is repetitive, unresponsive, visually crude, and conceptually shallow. Its gameplay loops are trite, its progression is illusory, and its license is used not as a strength but as a shackle. It is, in simple terms, a piece of licensed shovelware.

Yet, it is also extraordinarily significant. This is its true value, and why it must be studied.

Recap of Failure: It failed its Publisher (Vivendi) by targeting a non-existent PC market. It failed its Franchise (Butt-Ugly Martians) by not capturing the show’s soul (the friendship, the satire) or its time (the show ended in 2003). It failed its Audience (kids, parents) by offering a trivially short, unengaging, overpriced experience that was outclassed by free browser games the very next year. It failed Technologically by clinging to a hybrid 3D engine long after the death of Macromedia Director as a gaming platform. It failed Artistically by prioritizing expensive voice acting (120 voices!) over playable innovation.

Recap of Significance: But in failing, it became a perfect specimen. It is a “meta-failure,” a game that, in totality, demonstrates the forms of licensed game mediocrity in the early 2000s: the minigame boom, the PC market collapse, the voice acting arms race, the technological compromise, the financial pressures of franchising, the cultural inertia of “cartoon-based games,” and the epistemology of oblivion – how games are not just “forgotten” but designed to be forgotten.

The Verdict: Butt-Ugly Martians: Martian Boot Camp does not belong in the pantheon of “great games.” It does not belong on a “complete” 2000s PC collection. It belongs in a museum of video game history – specifically, in a hall labeled “The Failed License: Case #421, The PC Diaspora.” It is the digital equivalent of an expired coupon, a real but abandoned passport, a machine that spent its life in a closet, never used. Its place in history is not one of pride, but of painful, back-of-the-stack embarrassment – the kind that earns a footnote, not a legacy. It is the Québéc Citrouille of North American video games: a local oddity, preserved only for its absurdity, its forced branding, and the painful reminder of a time when the entire mechanics of licensed content felt like a performance for investors, not for players. It is a game that died so that modern digital preservation could practice a lesson: not everything needs to be saved – but everything that is forgotten reveals the shape of the caste system of digital culture. This isn’t a game. It’s an artifact of the architecture of failure. Rating? 2/10 – the 2 for the ghostly nostalgia, the 10 for everything else.

But commit this to digital fire: if you find an original copy, don’t play it.

Preserve it. Let its silence speak.