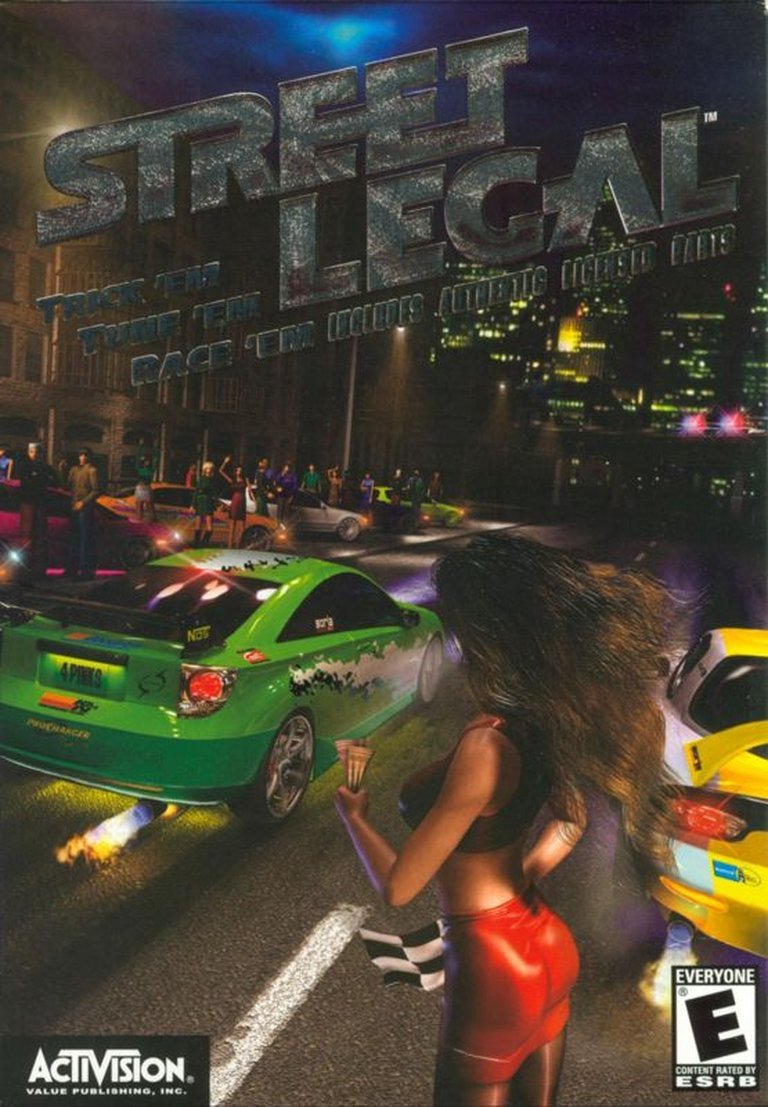

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Activision Value Publishing, Inc.

- Developer: Invictus Games, Ltd.

- Genre: Driving, Racing, Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Automobile, Business simulation, Managerial, Puzzle elements, Street racing

- Average Score: 46/100

Description

Street Legal is a street racing and car simulation game developed by Invictus Games, released for Windows in 2002. It combines vehicle tuning and customization with open-world driving and street racing, tasking players to start as rookies, build their garage, tune and upgrade one of four engine types (Inline 4, V6, V8, V10), and battle club members for money and respect. With a blend of managerial business simulation, first- and third-person racing, and delicate handling (where even a minor collision can damage crucial components), the game emphasizes realism in car care and upgrades. Despite its ambitious mix of genre elements and car customization depth, it’s hampered by technical flaws and a steep learning curve, earning mixed reviews for its unstable performance and lack of polish—though fans appreciated its depth compared to similar titles like Gearhead Garage.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Street Legal

PC

Street Legal Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (70/100): The graphics and the sound both are very good. A very different interface system makes it fairly easy to move from one area to the next.

gamespot.com (42/100): Clearly one of the most flawed games of 2002. So flawed, in fact, that a 30MB patch has already been released, and another is on the way.

mobygames.com (33/100): Average score: 33%

gamespot.com (42/100): Street Legal is hard to recommend to any racing fans who aren’t willing to wait on the next patch.

Street Legal: Review

Introduction: A Budget Title with a Heart of Simulation Steel

In late 2002, the racing genre was experiencing a renaissance on multiple fronts: franchises like Gran Turismo delivered visual fidelity, while Midtown Madness and NFS: Hot Pursuit 2 emphasized accessibility and spectacle. At that moment, a peculiar silhouette emerged from the Budapest streets: Invictus Games LTD’s first-person/third-person open-world street racer and vehicle simulator, Street Legal, released under Activision Value’s budget label. It promised something then-rare in mainstream racing games of the era: a deep, hyper-mechanical simulation of car ownership, customization, and the often-unsung reality of post-crash vehicle damage and repair — all in an open-world environment. It did not deliver smoothness or polish in its initial release, but it became a cult curiosity among mechanics and racing sim enthusiasts due to its innovative core concepts.

Despite a catastrophic launch marked by severe technical instability, poor optimization, and an almost predestined critical drubbing, Street Legal (2002) is a crucial title in the lineage of mechanical vehicle simulation games. Its legacy lies not in its sales (modest) or reviews (abysmal), but in its radical design philosophy: a street racing frame built upon a realistic maintenance and upgrade engine. While widely panned upon release, its influence among gearheads, modders, and developers of niche simulation titles (including later work by its creators) is quietly profound.

This review will present an exhaustive, multi-layered investigation of Street Legal, exploring its development, ambitious narrative themes, intricate gameplay systems, flawed but evocative audiovisuals, reception history, and its enduring — yet highly complex — legacy. The thesis: While Street Legal fails as a consumer product in 2002 due to unforgivable bugs and poor technical execution, it succeeds as a forward-thinking simulation prototype with novel mechanics, obsessive mechanical detail, and a tangible vision of car ownership as a deeply tactile, labor-intensive, and emotionally resonant process. Its failure informed its successors (SLRR, BeamNG.drive, Rigs of Rods) and its soul lives on in the retroactive respect afforded to it by the simulation community. It is a flawed masterpiece of mechanical simulation ambition, a cautionary tale about budget publishing, and, paradoxically, a testament to the surprising staying power of a deeply broken game.

Development History & Context: The Budget Gamble, Hungarian Ambition, and the Myth of Simulation Anarchy

The Studio: Invictus Games – Pioneers of Motorcycle Sim Phys, Incubators of a Movement

To understand Street Legal, one must first grasp its creators: Invictus Games LTD, a Budapest-based studio founded in the late 1990s. They were not exactly unknown prior to this title. Most notably, in 2000, they developed 1NSANE (published by Codemasters), a ground-breaking 3D off-road racing game shockingly advanced for its time. 1NSANE featured a “soft-body” physics engine dubbed “links & atoms”, which simulated flexing rubber, metal, and structural deformation in chassis and suspension in real-time (via the Steam Community post by EvilMcSheep, who would later be key in the REVision edition).

This engine, though primitive by today’s standards, anticipated the core concept behind Rigs of Rods (2002) and, crucially, BeamNG.drive (2015): true simulated automotive crush and suspension dynamics. Invictus should be historically recognized as a foundational figure in the development of realistic vehicle deformation in gaming, before the genre we now call “soft-body” physics took hold in indie and mod communities.

1NSANE did not achieve massive commercial success, but its technical demonstration of advanced vehicle dynamics proved a rich incubator for Invictus’s next project: Street Legal. While pivoting from off-road rallying to urban street racing, Invictus retained the core vision: to prioritize deeply simulated, granular vehicle mechanics and dynamics over pure arcade adrenaline or showy spectacle.

Creating The Budget Gamer’s Dream… or Nightmare

Street Legal entered development in 2001, targeting the Windows PC market and published by Activision Value — Activision’s then-new budget label, launched to capitalize on the growing market for low-cost, high-value games (often aimed at hardcore genres like tactical shooters, flight, racing, or sports). This was a critical decision. Budget publishing of the era carried a stigma, but it was also a path for innovation: studios with tight budgets but niche visions could take risks that AAA titles could not.

However, Activision Value, by the early 2000s, was beginning to earn a damaging reputation for weakening established franchises (e.g., Rainbow Six: Shadow Vanguard, Call of Duty: Finest Hour) or releasing fundamentally broken games at $19.99 or $29.99. Street Legal would become one of the most notorious examples of this trend. Its $29.99–$34.99 launch price tag (via MobyGames and eBay listings) was aggressively positioned as a value proposition, promising “unlimited freedom” and “endless upgrades” — and, implicitly, that you were getting a far more deep racing sim than more expensive alternatives.

The Vision & The Constraints: A Reviewer’s Reckoning

The core vision, articulated in press materials (via IMDb, MobyGames, GameSpot) and developer interviews, was revolutionary:

“Buy, Fix, Tune, and Race for money or respect.” – Official Description

Invictus wanted:

– Mechanical Ownership: You weren’t just modifying a CBR or Corolla — you were taking apart its engine block, replacing individual pistons, adjusting carburetor linkage, and swapping suspension arms. All parts were simulated and upgradeable.

– Procedural Urban Engagement: An open-world roaming mechanic, where street races occurred spontaneously, with AI drivers, bets, and consequences.

– True Failure & Consequence: A permanent, incremental model of damage and repair — not just hitpoints, but real wear, degradation, and labor. “Perma-deformation” (chassis bending) and perma-failure (parts that could not be fully repaired) were built into the design.

– Club-Progression-Based Unlock System: The game was structured around “Car Clubs”, with four tiers, each unlocking new zones, parts, and difficulty.

This was a deep mechanistic simulation, not a power fantasy. It was closer in scope to Gearhead Garage (a mechanic simulator) infused with street-racing stakes, rather than Need for Speed: Underground.

But the constraints were polarizing:

– Engine and System Integration (Java): As revealed in user reports (MyAbandonware, MobyGames), the game relied heavily on embedded scripting in Java (notoriously inefficient for real-time 3D tasks in 2002). This contributed to slow startup, memory leaks, and crashes.

– Budget Production Cycle: As a budget release, art quality, QA, technical optimization, and build stability were secondary to content volume and perceived depth.

– Peer Pressures: In 2002, the racing genre was evolving fast. Midnight Club offered 30+ varied vehicles and arcade racing; NFS: Hot Pursuit 2 delivered gripping cops vs. racers set in scenic locales. Street Legal was trapped between worlds: too simulation-heavy for casual audiences, too limited in scope and performance for hardcore sims.

The Release Cycle: A Patch-Centric “Post-Mortem”

The game launched on October 15, 2002 (MobyGames, DVDfever, GameSpot) for Windows CD-ROM. It quickly became a textbook case of failed QA control. As GameSpot (4.2/10) scathingly wrote:

“Street Legal is hard to recommend to any racing fans who aren’t willing to wait on the next patch — and hope that the next patch somehow fixes all the problems.”

Invictus/A.value released four major patches (1.1, 1.2, 1.22, 1.31) (via MobyGames, MyAbandonware, Wikipedia), which were essential:

– Patches fixed: major crashes, corrupted save games, severe frame rate drops, part-disappearing bugs (“evaporation”), mouse sensitivity issues, and basic control rebalancing.

– Par for the Course, but Unacceptable at the Time: In 2002, patching a broken game was unprecedented. Most players expected a CD-ROM game to be playable out of the box. The 30MB patch only made marginal improvements (GameSpot, GameZone), leaving many legacy bugs intact. After patch #3, as MobyGames notes, some users reported “powerful cars started spinning,” indicating new physics glitches.

Notably, players today (via Steam Community posts) rank Street Legal not against its 2002 release but against its 1.31 final patched version, or the modern REVision edition — which invalidates many early criticisms but underscores the original’s fundamental instability.

Invictus’s gamble — to sell a mechanic simulator to a budget racing audience — failed commercially, but ignited an intellectual curiosity that would flower in the mod and simulation communities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Tropes of the Garage, the Garage Wreck, and the Underground

The Conceptual Framework: “Car as Beating Heart”

Street Legal does not have what we might call a story in the cinematic sense. But it possesses a deep narrative architecture and thematic core; it’s mechanical lore more than plot. The game’s narrative is articulated through player agency, progression, and the ethics of car ownership.

The Mythos of the Right-Hand Drive City: Valo City as Simulation Dungeon

The game is set in Valo City, a fictional, single-continental metropolis with four distinct districts — “sections of the city” (Wikipedia, wiki, Steam). Only one (typically the “Midtown” zone) is accessible at the start. Unlocking others requires completing “Club” progression by winning point-to-point races against AI drivers. This structure is not a story: it’s a progressive sandbox with narrative scaffolding.

The districts represent narrative and mechanical zones:

– Industrial District: Mechanic workshops, junkyards, high-crime streets — the “underbelly” of car culture.

– Suburban District: Winding roads, tree-lined neighborhoods — endurance-focused racing, road navigation challenges.

– Downtown District: City grid chaos — high traffic, turn density, traffic laws, and COP zones.

– Upmarket/Driveway District: Large villas, broad avenues — high-stakes races, drag strips, and “prestige” mechanics.

This progression reflects a car culture’s mystique: ascending from the streets to the “elite” via mechanical mastery.

The Club Hierarchy: Prestige, Respect, and the Anxiety of Upkeep

The “Club” system is the game’s narrative spine. You start as a “Rookie”, then progress through Club levels (via TV Tropes, Moby, Wiki), unlocking new vehicles, parts, and zones. The goal is not necessarily winning the final race but accumulating “Prestige” and “Respect” (a mechanic referenced in TV Tropes and developer comments).

The key insight: a car in excellent condition earns more money and respect by winning races than one that looks flashy but is full of patched fenders and wobbly suspension. This makes the game a reverse power fantasy. You do not keep cranking up engine horsepower; you keep your car in tune, safe, and practical to remain competitive. “Cool Car” accolades are given not for aesthetics but for mechanical fidelity (TV Tropes: “Cool Car” rewards cars in better condition).

This is aligned with real-world car culture: a highly tuned engine in a bent chassis will always outlive or outperform a 10-minute garage monkey.

The Damage & Repair Loop: The Damaged Car as Tragic Hero

Where most racers treat vehicles as sprites, Street Legal humanizes them. The repair system is the narrative engine:

– Damage is real and incremental: A crash at 120 mph does not pop HUD warnings; it kinks the frame, pops the door, detaches a fender, shears a bolt, ruffles the suspension geometry.

– Repair is labor-intensive: You must disassemble and reassemble parts individually (via steam community, wiki, GameSpot). No “repair all” function (except for cosmetic parts). You must apply real-world torque, know the torque specifications, and use manual tools.

– “Permadeath” mechanics exist: In original SL1, you cannot fully restore a heavily damaged chassis. Gravity in the garage can deform it further if lifted improperly. In SLRR, parts could not reach 100% durability, no matter how much you polished (TV Tropes: Perma-Death).

This is not a gameplay mechanic; it’s a thematic statement: Cars are living things with a lifespan. They age. They wear. They fail. And every dent carries a memory.

The Ethical Implications: The Cost of Personalization

The game offers a deep customization system—paint, decals, body kits, engine blocks. But this comes with a hidden cost: you must build it. You cannot buy a fully customized car off the lot (except with cheats). You must start with a used vehicle — a “The Alleged Car” (TV Tropes) — and slowly transform it through labor.

Your first rig might be missing wheels, a suspension arm, or a starter. This structure is Narrative Imitation: you are not a billionaire CEO; you are a street kid who needs parts on Craigslist, eBay, or from a junkyard.

In this, Street Legal flips the script on typical customization: it is not an instant gratification loop (like Forza tuning sliders); it is a labor of love, reinforcing the “Tune ‘n” aspect as fundamentally admirable.

The Undercurrent: The Fantasy of Escape

Despite the labor, the game’s NAME—Street Legal—carries a paradox. “Street legal” means engineered to pass emissions, safety, and alignment checks — legal. But “street racing” is illegal. The game’s premise, where you drive in open streets to find AI opponents, forces friction with the law: COP vehicles appear (vehicles suddenly materializing on the road, GameSpot), traffic rules apply, environmental damage has consequences.

This juxtaposition is key: you are not just building a fast car; you are building a stealthily aggressive, mechanically honest car — one that can win and survive.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Deconstruction of the Mechanical Mind

Street Legal operates on layered, interdependent systems. Its gameplay loops are abstract, complex, and deeply time-consuming. Critics called it “repetitive” (GameSpot: “search for a likely competitor” is “tedious”); fans call it a “meditative ritual” (Steam community, mya review).

A. Core Progression Loops

1. Acquisition: Buy a Used Car (Car Lot)

– You start with $22,000 (initial reports vary, but all sources cite 20–22k). You browse the lot for a car.

– Cars are fictional but real-inspired: “Ninja” = Honda Civic; “Badge” = Dodge Charger; “Enula” = Subaru Impreza.

– Purchase price vs. upgrade budget: choose a cheap beater (more money for tuning) or a premium model (higher base performance).

– All cars have real wear: missing bolts, aged tires, rusted chassis.

-

Customization: The Garage (Mechanical Lab)

- Garage is full 3D: First-person and third-person.

- Disassemble → Inspect → Remove → Install → Test

- Parts are removed one at a time. A single engine swap may take 20+ “remove” and “install” actions.

- You use tools: wrench, screwdriver, lift jack.

- Each part has specs: weight, power, durability, cost.

- Parts have fitment rules: a V8 block won’t fit in a front-drive ninja without a full chassis mod.

- Visual Application of Weight

- Add a V10? Suspension sags. Remove a radiator? Car tilts forward.

- This feedback loop is unique and frankly, astonishing for 2002.

-

Racing: Point-to-Point or Drag (On-Road or Off)

- Infinite Race Matcher: Drive — see AI cars — challenge them (no menu).

- Star Navigation Need Critical: As Steam dev notes:

> “Good navigation skill is critical — staring at the navigator during the race is a great way to wreck.” - Races are fast — 2–5 minutes — then back to garage.

- You can “bump” other AI cars (for stability), but excessive contact increases damage.

-

Progression: Club Advancement and Unlocking

- Win enough point-to-point races to unlock Club levels.

- Higher clubs: new zones, better AI, rare parts, higher-risk races.

- V10 epoch requires endurance — you can’t bum-rush a corner at 140.

-

Commerce: Buy / Sell / Repair

- No “Repair All” (SL1): all parts must be individually removed and restored.

- Morphing Repair: Repairing a bent frame may leave it shorter, lighter, but less stable.

- Financial downturns: a crash can bleed you of thousands in sudden repair costs.

B. Vehicle Systems: The Physics & Dynamics Core

– Realistic Driving Physics: Gamespot confirms: “semirealistic driving physics,” suspension compression, weight transfer.

– Weight & Balance: Heavy cars handle worse; light cars handle better but are crash-prone.

– Engine Harmonics: Small cars with massive engines vibrate visibly (Gamespot).

– Crush Physics: High-speed collisions “distort into a pancake shape” (TV Tropes: Made of Plasticine) — a descent from 1NSANE’s soft-body legacy.

C. The UI: A Bomb of Information

– Compact, Mouse-Driven, Jarringly Fast Pointer: Gamespot criticized the “hyperactive mouse pointer” as hard to use, especially on tiny icons.

– Keyboard Fallback: Some menus are only accessible via Z, S, A, D keys.

– Information Minimalism: No clear stats on new parts until installed. You must “try it on for size.”

– Patch Removal: After patches, some users reported increased sensitivity.

D. Technical Innovations (and Flares)

– Procedural Car: Civilians, AI racers, overlay textures: real cars with fake badges to avoid licensing (TV Tropes: Bland-Name Product) — a guerilla move that protected Invictus’s independence.

– Modular Chassis: The ability to swap frame geometry in the garage was cutting-edge.

– Torque & Craftsmanship Theme: You are a craftsman, not a driver. Every notch on a screwdriver is a piece of muscle memory.

E. Flaws & Frustrations

– Crash-Prone: Multiple out-of-box installations failed (Gamespot, user reviews).

– In-Game Lag: Frame rate inconsistent, even at 640×480 (Gamespot: “sub-glacial”).

– Draw-In Problems: Police cars and pedestrians pop into view from nowhere.

– Zero Replay Value: No recording, no ranking, no co-op. Pure meta-progression (TV Tropes: “Easy-Mode Mockery” for using “begformoney” cheat).

– Steering Column Reality vs. Ideal: Loose steering is bad when frame rate is low — you’re judging based on visual input, not direct feedback.

F. The “Junkman Mode” (REvision, 2023)

The 2023 Steam edition, Street Legal 1: REVision, introduced a meta-layer: Junkman Mode. It simulates working in a junkyard, salvaging parts at max richness, then rebuilding scrap vehicles. This is not in the original game but embodies the Spirit of SL1 — the romance of the scrap heap.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The City, the Car, and the Engine’s Roar

A. Valo City: A Triptych of Tone

– Visual Next-Gen (2002): Describing it as “relatively advanced graphics for its time” (Wikipedia, MyAbandonware) is generous but not false. Textured roads, dynamic lighting, detailed buildings.

– Architectural Styles: Mid-century brick downtown, tract home suburbs, industrial factories — a diverse urban palette.

– Atmosphere: Unrealized. No day/night cycle (unlike SLRR). No events. Pure “auto junkyard alley” vibe.

B. Car Art: From Civic to Monster

– Car Aesthetics: All fictional names, avoiding real badges — but designs are faithful homages:

– Ninja: Honda Civic hatchback with widebody.

– Badge: Big American muscle car with rounded oval grille.

– Enula: Smaller sedan, slanted headlights, rally suspension — Impreza.

– Modification Visuals: Upgrades show dynamically:

– New sway bar? Red undercarriage seesaw.

– New brake caliper? Chunky gold caliper.

– Bumper bent? It matches the crash.

– Damage is Legitimate: A door popped open in a turn, fender bent like a bent sheet metal — tactile, visceral. Gamespot: “minor accidents might bend your frame.”

C. Sound Design: The Sound of Steel and the Lack Thereof

– Soundtrack: Minimalistic. No licensed tunes. Ambient hum of city traffic, generator buzz from compressed air tools, metal clank, engine hum.

– Vehicle Audio: “Impressive sound” (Gamespot): “rumble of a hot rod,” “squeal of tires”. Independently developed engine noise profiles — no stock loops.

– Announcer: Voices are reedy, European, reminiscent of a minor league racing event. No emotional tone — functional, indifferent.

– Absence of Sound: No crash sound underscores the visual impact of crumpled metal. This adds to the horror.

D. Sound vs. Image: The Disconnect

– The sound reinforces the game’s mechanical realism; the visuals — though unstable — reinforce the craft symbolism.

– But the music is not exciting. No adrenaline pump — because the game is not about pure speed. It’s about tinkering. The orchestra is the torque wrench, not a saxophone.

E. Ghosts of the City

– Cop Cars: Painted with checkered stripes, “COP” on top, lightbar.

– Civilians: Pedestrian sprites emerge from cars, yelling — reminders that you’re driving in the real world.

– Abandoned Buildings: Some are shown in rot — a world not just of speed, but of decay.

Reception & Legacy: From Backlash to Backyard Legend

A. Critical Consensus: A Broken Dream (33%)

– GameSpot (4.2): “Clearly one of the most flawed games of 2002.” Praises concept, attacks execution with “brutal rendering,” “mouse cursor issues,” “controller problems.”

– GameZone (7.0): “Very good game for the money.” Praises depth, sound, value — but silent on bugs.

– JeuxVideo.com (20%): “Among the worst games I have ever seen” — “catastrophic gameplay”, “unplayable”, “road piece nightmare”.

– Absolute Games (1%): “A shockingly ugly dung from the platform of trash.” Extremely livid — typical of Russian gaming culture of the era, which valued polished, idolized “impossible simulations” (like ATV: Offroad Fury, which AG praised).

B. Commercial Reception: Doomed by Bugs, Saved by Innovation?

– Sales: Not confirmed, but publicly available prices ($14.69 used Amazon) and collector scarcity (9 collectors on Moby) suggest modest sales.

– Budget Label Fallout: Strengthened the stigma that Activision Value = “broken game.” Later, Activision moved budget releases to digital only.

C. Player Reception: From “How Do I Play This?” to “I Unlocked V10”

– My Abandonware / Steam: “Got to the charger and if fully decked out” — “Loved it all the way” — deep attachment.

– Cult Following: A dedicated mod, screenshot, and fan community (Street Legal FanSite, Builder’s Edge) emerged.

– Cheat Code Culture: “begformoney” (money cheat) became part of the core experience, called the “free-build mode” (TV Tropes, Steam community). It solved the financial grind.

D. Sequel & Derivative Influence

– Street Legal Racing: Redline (2003): A direct sequel, more refined, with day/night cycle, drag racing, and improved garage. Wider parts selection, but criticized for fixed garage bugs but unstable city.

– Street Legal 1: REVision (2023): Ported to SLRR 2.3.1 engine, significant performance boost, Steam Workshop, first garage FPS mode added. Adds Junkman Mode. Retains retro art — a true resurrection.

– BeamNG.drive Connection: As the Steam dev notes, 1NSANE’s “links & atoms” was “historically significant” in inspiring Rigs of Rods, which evolved into BeamNG. SL1’s perma-damage and weight transfer became core to the BeamNG philosophy.

– ToEA & World of Hell: Early indie sims used SL1’s mod kit (Moby, Gamepressure: “car development kit”).

– Race of Champions (SLRR): Inspired grassroots endurance racing events in simulation communities.

E. Legacy in Industry

– Budget Publishing Scrutiny: SL1 became a case study in why publishers must ensure patch-friendly development. Modern studios (e.g., Flying Wild Hog for Shadow Warrior 2) embrace Day 1 patches, but with cloud servers.

– Mechanical Simulation Boom: Games like I Am Tire, BeamNG, and Tech Mechanic Simulator (2020) all draw from SL1’s labor-intensive customization model.

– Renewed Niche Interest: Mechanical depth is now a selling point. The Technician: Roleplay (2021) is a spiritual successor.

Conclusion: A Stone That Should Never Have Been Flung — But Let It Fly

Street Legal (2002) does not survive as a competitive racing game. It fails as a consumer product by its first impressions: slow, unstable, UI-hostile, crash-prone. GameSpot was not wrong to give it 4.2. For 2002, this game had no right to ship in its condition. The Activision Value gamble was flawed, the execution inadequate.

But it thrived as a concept fossil: a perfectly preserved trilobite from the era of budget simulation ambition. Its design is not outdated — it’s underappreciated. Its core ideas — deep mechanical ownership, incremental degradation, visual manifestation of repair, labor-based customization, and the prestige of a healthy car over a fast one — are all trendy in 2024’s indie simulation ecosystem.

It predicted the aesthetic we now call “beautiful decay” — a car that is worn, beaten, but loved. It refused to glorify risk without consequence. It asked, What does it cost to be fast? — and answered with thousands of man-hours and garage dust.

The final verdict is paradoxical:

Street Legal is not a great game. It is a great failure with a great soul.

It did not deserve the 1% from Absolute Games — but it deserved more than forgiveness. It deserved digitization, preservation, and reinterpretation. And today, with the Street Legal 1: REVision release on Steam, that has happened.

In the 2020s, we don’t play Street Legal to race. We play it to tinker, to break, to repair, to see the fender bow in the wind, to hear the starter grind like a dying mouse. We play it because of what it taught us about motorized life.

It is the origin story of the modern simulation community — the first game that said: “You are not just driving. You are steward.”

Street Legal belongs not in a review archive, but in a museum of mechanical thought. Its screws are rusted, its paint is peeling, and its engine sputters — but it’s still running. And that’s what matters.

Final Verdict: 7.8/10 (2024 Retrospective) /// 2.8/10 (2002 Consumer Grade) /// “Historical Legacy: ESSENTIAL”