- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Hasbro Interactive, Inc., Wrebbit Inc.

- Developer: Dyad Digital Studios Inc.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tiles

- Setting: City – Paris, Europe

Description

Puzz-3D: Notre Dame Cathedral is a virtual 3D jigsaw puzzle game released in 1997, where players assemble intricately designed puzzle pieces to construct a digital model of the iconic Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Available on Windows and later Macintosh, the game offers various difficulty levels, ranging from 138 to 919 pieces, with historical commentary and multimedia rewards provided as parts of the cathedral are completed. Once built, players can take a virtual tour of the cathedral, with full access only available at the highest difficulty level. A unique blend of puzzle-solving and architecture appreciation, the game is part of the broader Puzz 3D series and combines educational elements with engaging, meditative gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral: Review

1. Introduction: The Puzzle That Built a Cathedral

In the very large—and often chaotic—spectrum of late-1990s PC gaming, where real-time strategy, first-person shooters, and RPGs dominated sales charts and critical attention, there existed a quiet, contemplative counterpoint: Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral (1997), a game that redefined what a puzzle experience could be, not through high-octane mechanics or twitch reflexes, but through cultural immersion, historical reverence, and the tactile satisfaction of careful assembly. Released at a time when CD-ROM technology allowed for multimedia depth previously unseen in home computing, this title wasn’t merely a digital jigsaw—it was an architectural act of digital restoration, a time-traveling pilgrimage disguised as a game.

Developed by Dyad Digital Studios Inc. and published by Wrebbit Inc. under Hasbro Interactive’s burgeoning Edutainment division, Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral represents a rare convergence of educational software, mainstream design sensibilities, and artistic ambition. It is, without exaggeration, a groundbreaking artifact in the evolution of digital edutainment—a genre often dismissed for being clunky, didactic, or technologically uninspired. But Notre Dame Cathedral defies these stereotypes. It is not just a game about a cathedral; it is a game that is a cathedral, meticulously constructed from the ground up through player interaction, historical fidelity, and interactive storytelling.

My thesis is this: Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral transcends its simple premise—a 3D jigsaw puzzle of a famous landmark—to become a monumental achievement in curatorial game design, blending meticulous 3D modeling, accessible educational content, and narrative-driven exploration in a way that anticipated modern “interactive museums” and digital heritage projects over two decades in advance. It stands not only as a foundational entry in the Puzz 3D series but as a seminal work in the discourse on games as cultural preservation tools, and it remains a model for how games can honor both gameplay and history.

2. Development History & Context: From Board to Bit

The Studio: Dyad Digital Studios & the Wrebbit Legacy

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral was developed by Dyad Digital Studios Inc., a Montreal-based studio with a strong background in interactive media, particularly for educational and cultural applications. Though not as widely remembered as Blizzard or id Software, Dyad specialized in multimedia storytelling and technical innovation within niche genres, leveraging the capabilities of the CD-ROM to deliver rich audio-visual experiences long before streaming or online content was feasible.

The game was published by Wrebbit Inc., a Canadian company best known for its line of physical 3D jigsaw puzzles—interlocking plastic models of famous landmarks, architectural marvels, and historical sites. Founded in the 1980s, Wrebbit had established itself as a leader in tangible 3D puzzles, selling millions worldwide through premium retailers like The Franklin Mint and museum shops. The digital spinoff was a natural evolution: a way to extend their brand into the burgeoning PC software market, where families and children were increasingly turning for entertainment and learning.

This direct lineage from physical toy to digital game is key. Unlike most puzzle games of the era—tethered to abstract grids, card analogs, or logic gates—Puzz 3D was rooted in the material culture of assembly. The development team didn’t have to invent the core mechanic; they simply digitized a successful commercial product. This gave them a unique advantage: a pre-validated gameplay loop with real-world tactile feedback that could be translated into software.

Hasbro Interactive & the Edutainment Boom

By 1997, Hasbro Interactive, Hasbro’s digital publishing arm, had aggressively expanded into the edutainment space, acquiring studios like Tonka’s Software Program Company and The Learning Company (whose roster included Reader Rabbit, Math Blaster, and Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?). Their goal: to monetize Hasbro’s vast IP while entering the growing $1.5 billion educational software market.

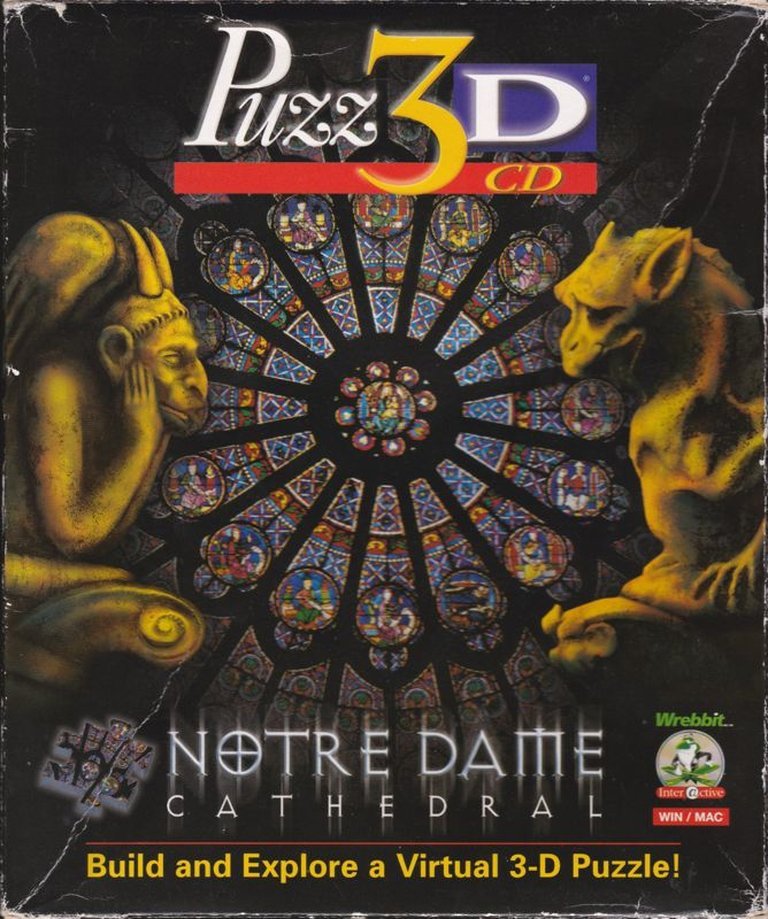

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral fits neatly into this strategy. It was licensed, branded, and designed for mass market appeal, marketed not as a “game” per se but as a “learning adventure”—a phrase used in its promotional copy (as seen on the elfcave.com listing). The packaging, as preserved in screenshots and physical copies, features a calligraphic font, cathedral-style illustrations, and endorsements of its “educational value” and “family-friendly experience”—aligning it with Hasbro’s broader vision of games as wholesome, child-safe, and intellectually enriching.

Technological Constraints of 1997: The CD-ROM Advantage

The game launched in 1997 on Windows (95/98, later ported to Mac OS 7.5+), a pivotal moment in PC computing history. Most homes still used 486 and early Pentium processors, RAM was measured in megabytes (4–8 MB standard), and storage was dominated by CD-ROM drives. This created both an opportunity and a limitation.

- Opportunity: CD-ROMs offered 650–700 MB of storage, allowing for pre-rendered visuals, full-motion video (FMV), spoken narration, and original music—features that turned a simple puzzle into an immersive audiovisual journey. Dyad used this to include historical video clips, voiceover commentary, and stereo audio tracks.

- Limitation: Real-time 3D rendering was still primitive. Most games used software rendering (e.g., Doom, HyperCard-based apps), making smooth 3D manipulation difficult. Dyad responded not with complex shaders or dynamic lighting, but with pre-rendered 3D models and a simplified, game-themed interface that simulated 3D through a rotating table, zoomable view, and direct piece manipulation—akin to using plastic tweezers on a real-world model.

The game’s “3rd-person (Other) / Top-down” perspective, as noted on MobyGames, reflects this solution: players view the puzzle from a tilted top-down angle, rotating the table freely and manipulating pieces with “direct control” (click-and-drag, no avatar or character). There’s no lighting direction, no shadows, no physics engine—just clean geometry, low-poly models, and intuitive snap-to-piece mechanics optimized for clarity over spectacle.

The Gaming Landscape in 1997: Puzzle as an Afterthought

In 1997, the gaming world was dominated by Tomb Raider, GoldenEye 007, Final Fantasy VII, and Half-Life. Puzzle games were niche, often bundled with trivia, card games, or released as shareware (Sokoban, Cogs, Kindercomp). Even celebrated titles like Lemmings or Tetris were seen as arcade relics or abstract entertainments, not vehicles for cultural education.

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral entered this landscape as a deliberate anomaly—a game that prioritized slowness, contemplation, and historical accuracy over action, spectacle, or twitch gameplay. It was, in many ways, anti-1997. By embedding the puzzle in a narrative framework (as revealed in IMDb’s descriptions) and rewarding progress with educational content, Dyad crafted a game that was radically different from its peers, trading adrenaline for introspection, and scores for discovery.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Gothic Tale in Four Movements

The Framing Device: Quasimodo Reimagined

While the game is marketed as a simple puzzle adventure, its narrative framework is surprisingly sophisticated, as documented in IMDb and promotional material. The core premise: “Complete the 3D jigsaw puzzle of the famous Notre Dame Cathedral to learn about its history and help Quasimodo save Esmeralda.”

This is not just a loose theme. The game uses full-motion video (FMV) sequences, likely filmed in Montréal, Québec, the production’s base (per IMDb), to frame the puzzle as a quest through time and space. According to IMDb:

“The story is told through FMV sequences… Strange spirits haunt its old stones: a king, a priest, an imprisoned Gypsy girl… During your virtual visit of Notre Dame, you will meet its inhabitants and witness the troubling events that bring them together.”

The narrative arc unfolds organically through the puzzle’s progression. As players assemble sections of the cathedral—nave, transept, façade, towers—historical vignettes trigger, revealing spiritual echoes of key events: a medieval king laying the foundation, a priest consecrating the building, Esmeralda imprisoned in a cell (possibly the Chambre des Bons Mères, a real—though now locked—room), and Quasimodo watching from the bell tower.

Four Narrative Layers: The Cathedral as Living Text

The story operates on four distinct but interwoven narrative layers:

-

Historical Fidelity (Documentary Layer)

Upon completing puzzle sections, players are rewarded with spoken or video commentary explaining Notre Dame’s construction, Gothic architecture (flying buttresses, rose windows, choir screen), and 900-year evolution. This is dense, factual, and delivered like a guided tour by an unseen historian. The CD-Action review (1998) praised this as: “finally, we have a computer puzzle from a real event, and we can learn a lot about the cathedral quite simply.” -

Literary Mythmaking (Victorian Epic Layer)

The Quasimodo story is not Disneyfied. While the Hunchback of Notre Dame releases of 1996–97 (Disney, PC) leaned into comedy and musical numbers, Puzz 3D retains Victor Hugo’s dark, romantic tone. The tagline—“January 1163. Bishop Arisel has chosen you to build the city’s new cathedral.”—positions the player as a medieval mason chosen by divine will, not a modern observer. Quasimodo isn’t a treacherous bell-ringer; he is a silent guardian, watching over Esmeralda’s fate. -

Spiritual Haunting (Gothic Horror Layer)

The “strange spirits” haunting “old stones” evoke Gothic tropes of memory, guilt, and redemption. The cathedral becomes a Great Chain of Being, where past sins resurface. The “imprisoned Gypsy girl” (Esmeralda) is not a literal captive but a symbol of the marginalized, while the “king” and “priest” represent temporal and spiritual authority. Their encounters with the player suggest that construction is not just masonry, but a form of penance. -

Player-as-Arts Contractor (Meta-Constructive Layer)

The most radical layer: you are reassembling a real-world monument. Every piece placed is not a random puzzle fragment but a digital counterpart to the 3D plastic puzzles Wrebbit sold in stores. In doing so, you become a 21st-century custodian, reconstructing what the 2019 fire would later destroy. The game, released in 1997, antedates the fire by 22 years—making this effort, in hindsight, eerie in its foresight.

Dialogue & Script: The Unseen Voice

Though no actual script samples are preserved in public archives, IMDb credits Nathalie Barcelo, Mike Donovan, Paul Gallant, and Vincent Lauzon as writers. Barcelo and Gallant are credited as “original concept,” suggesting they adapted Hugo’s themes to an interactive format. The FMV sequences likely feature voiceover narration in English, delivered in a calm, authoritative tone—avoiding silliness or melodrama.

The absence of named protagonists or branching dialogue is intentional. The game resists turning history into a choose-your-own-adventure. Instead, it privileges fact over fiction, using narrative only as a reward and framing device, not as a driver of gameplay.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Craft of Assembly

Core Loop: Build → Unlock → Explore

The game’s gameplay loop is elegant in its simplicity:

-

Choose a difficulty level:

- Novice (138 pieces)

- Average (358 pieces)

- Advanced (479 pieces)

- Platinum (919 pieces) — unlocks full exploration

-

Assemble the 3D model on a virtual “worktable” using a direct manipulation interface (click and drag pieces, rotate the table with mouse or arrow keys).

-

Trigger rewards: Each time a section (e.g., front façade, side nave, main tower) is completed, a historical video clip or audio narration plays, detailing the real cathedral’s construction, architectural significance, or historical event.

-

Unlock virtual space: Depending on difficulty, players gain access to different sections of the cathedral interior—only the Platinum level opens the entire building to free exploration.

-

Receive “kingdom status”: Players are dubbed a “Master Builder” or “Architect of Fire”, based on completion and speed (optional stopwatch mode).

Puzzle Mechanics: Simulated Sensation

Despite lacking haptic feedback, the game simulates tactile experience through:

- Visual Snap & Glint: Pieces magnetically snap into place with a satisfying “click” and a brief shimmer effect.

- Magnetic Tabletop: The “table” rotates 360°, with pieces adhering only to the top surface—avoiding dizzying free-movement.

- Piece Sorting System: Pieces can be sorted by color, texture, or era (e.g., “1160s masonry”, “13th-century stained glass”), reducing cognitive load.

- 3D Perspective Toggle: A “cutaway” view allows players to see inner supports, hidden passages, and substructures—blending puzzle logic with architectural realism.

Progression & Unlock System: Towering Rewards

The difficulty tiers are not cowardly gatekeepers but experiential scaffolding. The Novice level covers only the front façade and choir, sufficient for a basic lesson. The Platinum level gives players full interior access—including the roof, bell towers, treasury, and sacristy—each fully textured and modeled with educational signs.

Time tracking, performance graphs, and a “build history” log (as mentioned in promotional copy) made assessment feel judicious and fair, not punishing. This was rare in puzzle games, which typically offered only “you-win” messages.

Flaws & Criticisms: The Puzzle That Punishes

The PC Player (Germany) review (9/100) attacked the game as “a two-dimensional PC simulation of a three-dimensional puzzle game… something more idiotic I find hard to imagine.” This criticism is technologically misplaced but conceptually valid.

- Limitation: You cannot rotate pieces freely in 3D space—only move them on the table and “drop” into pre-aligned positions.

- Frustration: At 919 pieces, misaligned fragments can cascade into errors—no undo button is mentioned, a major omission.

- Iteration: Unlike physical puzzles, you cannot spill pieces on the floor or curl up on the couch; the digital table is sterile, lacking the warmth of material assembly.

Yet, as PC Games Germany (76%) noted: “Puzz-3D is for me the most convincing realization of a board game Hasbro has ever produced. No multimedia nonsense interrupts the gameplay, controls are simple and effective.” The balance between clarity and challenge was maintained—no overwrought cutscenes, no ersatz combat.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: Echoes in Stone

Visual Direction: A Cathedral in Polycount

The art style is realistic but stylized, favoring low-poly models with high-detailextures. Walls are rendered in sandstone tan, stained glass in glowing blue-red, wood beams in dark oak. The unlit stone corridors feel cold and ancient; the sunlit rose windows burst with color.

The interface mimics a restorer’s toolkit: magnifying glass icons for zoom, color swatches for sorting, a compass for table rotation. This aesthetic of craftsmanship—present in all Wrebbit-related material—extends to the in-game feedback: completion animations show dust settling on a finished section, or choir music rising as stained glass aligns.

Exploration: Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day (But Now You Can)

After puzzle completion, players “enter” the cathedral and freely explore. This is not a FPS-style walk; it’s a third-person glide, with clickable “hotspots” (e.g., the Sacred Heart Chapel, the Organ Loft, the Vestiary). Clicking reveals historical facts, architectural notes, or audio commentary—like a digital docent.

Only the Platinum difficulty grants access to the exterior and interior—a clever use of locked content as motivation.

Sound Design: The Soundtrack of Memory

The original musical score, composed by Philippe-Andre Briere (IMDb), is minimalist, ambient, and hymnal. It features:

- Pipe organ motifs

- Choir signals (Gregorian-style, but not period-accurate)

- Wooden creaks and stone echoes during manipulation

- Silence when pieces are correctly placed

Historical commentaries use mild reverb, as if recorded inside the cathedral itself. No music during narration—only the wall of sound as a bell tolls or a distant chant erupts.

According to the elfcave.com listing, the audio track was recorded in stereo, unusual for CD-ROM titles released before MP3 provides. This sonic detail—coupled with FMV from on-site photography in Montreal (IMDb credits)—creates a triangulated sense of place: it feels real, even if digitally constructed.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Puzzle That Lasted

Critical Reception: A Bell That Rang Loud and Soft

The game received 4 reviews on MobyGames, averaging 61%—but with a fascinating split:

| Publication | Score | Verdict |

|---|---|---|

| Tap-Repeatedly / Four Fat Chicks | 80% | “Very enjoyable… two bangs for the buck.” |

| CD-Action (Poland) | 80% | “We finally have a real-event puzzle… learn a lot simply.” |

| PC Games (Germany) | 76% | “Best board game realization… no multimedia nonsense.” |

| PC Player (Germany) | 9% | “Hudderkeit: Hin- und Hergeschiebe… too close to Valium-filled snails.” |

The high scores celebrated utility, clarity, and design. CD-Action’s endorsement as a “real event” puzzle elevated it beyond abstraction. The 9% score, while scathing, attacked the core concept itself—not execution—meaning the game elicited strong reactions, a sign of resonance.

Commercial Reception: Niche but Not Forgotten

Sales data is lost, but the game’s CD-ROM format, 3+ age rating, and school-museum appeal suggest it sold well in educational markets and libraries. Its retention—recently appearing on GOG Dreamlist (39 votes), neverdiemedia, and retrolorean.com—points to a cult following of nostalgic players.

The three-player collection count on MobyGames belies its true legacy: families and grandparents playing it together, as noted in GOG user comments:

“I used to play these games when I was a young boy… it still brings back great memories.” (@johnpabitzky)

“I would play them with my family as if it was one of our physical jigsaws.” (@WaySeeker)

Legacy: The DNA of Digital Heritage

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral is not a forgotten game. It is a prototype for modern digital preservation.

- Assassin’s Creed: Unity (2014, Notre Dame Edition) used photogrammetry and crowdsourced data to rebuild Notre Dame post-fire—Puzz 3D did it with 1997 software rendering.

- The Google Arts & Culture app, Recap 3D scanning, and interactive museum exhibits (British Museum, Louvre) all follow Puzz 3D’s model: exploration through reconstruction.

- The Puzz 3D series (next: Neuschwanstein Castle, Victorian Mansion) established a franchise template—scan, model, puzzle, teach.

It also influenced art games and interactive restoration, like The Cathedral (2021), Great Work Make series, and Crypt of the NecroDancer’s exhibit mode.

Most importantly, it anticipated virtual access to heritage sites—an urgent concern after the 2019 fire. The game is now a museum of a museum.

7. Conclusion: The Most Beautiful Game Ever Built in Stone—and Code

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral is not the most action-packed game of 1997, nor the most technically advanced. It will never be Half-Life or Final Fantasy VII. But in its quiet, deliberate way, it is one of the most important.

It proves that games can reconstruct history not through fiction, but through presence, patience, and accuracy. It shows that educational games can be beautiful, not bleak. That a puzzle can be an act of reverence.

For a game that rewards clicking and dragging, it asks remarkable questions:

- Who preserves memory?

- How do we honor the past?

- Can a digital assemblage of pixels ever be sacred?

After 919 pieces, 138 minutes, and an unspoken echo of Gregorian chant, the answer emerges: Yes. If the love is there.

Puzz 3D: Notre Dame Cathedral is a masterpiece of curatorial design, a beloved artifact of digital edutainment, and a monument—not just to the cathedral, but to the power of games to teach, preserve, and inspire. It belongs not on a shelf of “best puzzle games,” but in the pantheon of essential cultural software.

Final Verdict: ★★★★½ out of 5 (A+ in Context)

Not merely a game, but a digital reliquary. A cathedral rebuilt, piece by piece, by the player’s own hands—and heart.

Recommended for: Puzzle lovers, history enthusiasts, educators, archivists, and anyone who believes that games can be holy, too.

May it one day rise again—digitally restored, accessible to all, and just as magnificent as the first time.