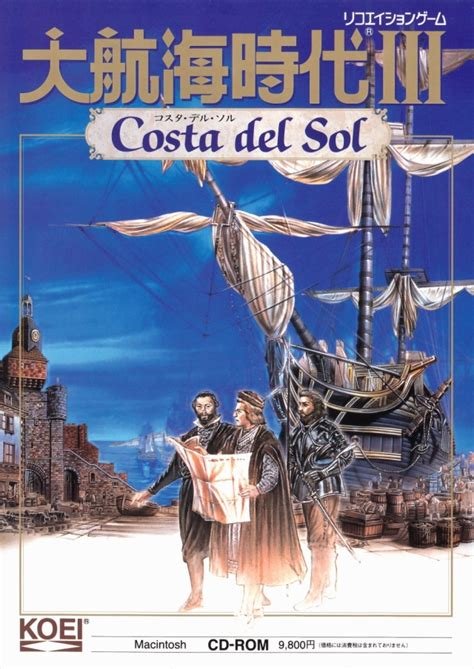

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Bisco Co., Ltd., KOEI Co., Ltd.

- Developer: KOEI Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG), Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: 2D scrolling, Discovery, Exploration, Family empire building, Historical events, Naval combat, Real-time, Trade

- Setting: City – Lisbon, Historical events

- Average Score: 100/100

Description

Set in 1480, Daikōkai Jidai III: Costa del Sol shifts focus from trade to exploration and discovery, allowing players to create their own protagonist or choose between a Portuguese or Spanish adventurer. As a historically inspired naval RPG, the game emphasizes finding geographical, biological, religious, and historical discoveries across a 2D scrolling world, where reporting these to sponsors yields wealth and fame. Players sail with legendary real-world navigators, potentially achieving feats like discovering the New World before Columbus or India before Vasco da Gama, earning naming rights and prestige. Romance is woven into gameplay, enabling courtship with women across cultures, marriage, and building a multi-generational family empire. Despite its depth and realism, the game’s steep difficulty and demanding mechanics made it the least popular entry in the otherwise celebrated Uncharted Waters series.

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : It is the most realistic title among the whole series, unfortunately, accordingly the most difficult and frustrating one, making it the least popular in both Japanese and global market.

myabandonware.com (100/100): There is no comment nor review for this game at the moment.

Daikōkai Jidai III: Costa del Sol: Review

Introduction: The Ambition of the Uncharted Waters Series, Realized—and Challenged

Few games in the history of Japanese video game design embody the paradox of ambition versus accessibility as starkly as Daikōkai Jidai III: Costa del Sol (also known in the West as Uncharted Waters III). Released in late 1996 by Koei Co., Ltd., this third installment in the legendary Uncharted Waters series marked a radical departure from its predecessors, shifting the franchise’s focus from the economic simulation of global trade to a deeply historical, experiential exploration of the Age of Discovery. Set in 1480, at the dawn of the Portuguese and Spanish golden age of navigation, the game invites players to step into the boots of a self-created mariner or one of two pre-fabricated protagonists from Iberia—each with unique political, cultural, and narrative potential.

But Costa del Sol is not merely a historical reenactment; it is a monumental simulation of discovery, a sprawling, systems-driven RPG that merges naval strategy, real-time exploration, social romance, and character lineage into a singularly intricate experience. My thesis is this: Daikōkai Jidai III: Costa del Sol is the most authentic, ambitious, and intellectually rewarding entry in the Uncharted Waters series—yet it is also the most frustrating, demanding, and unforgiving, a masterwork of design that deliberately resists the player’s comfort, sacrificing popularity for historical fidelity and systemic depth. It is a game that was meant to be difficult, not due to design failure, but because it sought to mirror the overwhelming realities of 15th-century exploration—where knowledge was scarce, dangers were everywhere, and success was earned not by clicks, but by years of painstaking effort.

This review will dissect Costa del Sol not as a nostalgic retro title, but as a serious work of interactive historiography, a sophisticated digital narrative of empire, discovery, and human ambition.

Development History & Context: Koei at the Crossroads of Genre and Era

Koei Co., Ltd. in the Mid-1990s: A Studio Defined by Hybridity

By 1996, Koei had cemented its reputation as a pioneer of historical simulation games, with franchises like Dynasty Warriors (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), Ninja Gaiden (in its original form), and Genghis Khan already successful. Yet Daikōkai Jidai (Uncharted Waters) stood apart as the studio’s most experimental series, blending RPG progression with naval strategy and economic simulation. The first game (1990) introduced the concept of global trade and naval combat; the second (New Horizons, 1993) expanded it with executive gameplay—long-term planning, crew management, and ship customization—making it a cult classic.

Costa del Sol, released on November 29, 1996, for the Windows platform (with a Macintosh port in 1997), emerged during a critical juncture in Koei’s history. The studio was transitioning from 16-bit console roots to PC-based, multimedia-rich simulations, leveraging the growing capabilities of the Microsoft Windows 95 environment. The game was built using 2D raster-based graphics with isometric and top-down perspectives, animated with smooth scrolling maps and real-time ship movement across a digitally reconstructed Earth based on Ptolemaic and medieval cartography.

A New Vision: From Trade to Discovery

The shift in focus from trade (the core of Daikōkai Jidai II) to discovery in III was intentional and profound. According to design ethos drawn from Koei’s internal historical research team (a feature of their simulation games), the developers wanted to capture the spirit of the Age of Discovery as chronicled in Iberian chronicles—particularly the Regimiento de Navegación (15th-century navigation manuals) and the mittelalterliche Seefahrtskunde (medieval maritime science). This was not about amassing gold for profit, but about naming continents, rivers, and seas—achieving immortality through geography.

The game’s subtitle, Costa del Sol (“Coast of the Sun”), refers to the Spanish name for the Andalusian coast—symbolizing the warm gateway to the hopes and horrors of global exploration. Bisco Co., Ltd., a Japanese distributor specializing in PC games, co-published the title, helping Koei reach a broader PC audience at a time when console gaming dominated Japan.

Technological Constraints and Innovations of the Era

The Windows 95 platform allowed Koei to implement a real-time, persistent game world with:

– Simultaneous navigation of multiple ships (a first for the series)

– Day/night cycles and seasonal weather effects

– Complex ship systems (masts, rigging, damage states)

– A dynamic discovery and knowledge system where new information had to be reported to client patrons for rewards

Yet the game pushed the limits of early-PC capabilities. The 572 MB Mac version (as documented by My Abandonware) was massive for its time, featuring extensive dialogue trees, multilingual assets, and a sprawling world map. The game lacked the polygon cruelty of 3D Nor dying games, but it maximized 2D depth through procedural generation of hidden features, layered UI menus, and a real-time clock that advanced even when the game was paused (a subtle design decision emphasizing the passage of actual historical time).

The decision to make the game Windows- and Mac-exclusive also insulated it from the emergent console culture (e.g., PlayStation), allowing Koei to design a game for patient, detail-oriented players—a demographic they believed would appreciate the depth.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Geography of Human Desire

1. The Dual Protagonist and the Illusion of a Single Hero

Costa del Sol offers players a choice: create a fully custom protagonist or select one of two pre-fabricated characters—a Portuguese and a Spanish noble. This duality is more than a gameplay option; it’s a thematic device exploring national ambition, colonial rivalry, and personal destiny.

- The Portuguese protagonist begins with access to the School of Sagres, symbolic of Portugal’s systematic approach to exploration. Their narrative is rooted in scientific mastery—accurate maps, celestial navigation, and the gradual conquest of the African coast.

- The Spanish protagonist, by contrast, starts in Seville, caught between political intrigue and the looming possibility of transatlantic ventures. Their arc mirrors Ferdinand and Isabella’s patronage of Columbus—less methodical, more driven by Leyenda Negra-fueled urgency.

Players who choose a custom character face the steepest challenge: no narrative immunity. They must build their name from nothing, and every choice—from which port to register in, to which historical figure to align with—carves a unique path. The game rewards players who identify with historical actors (e.g., sailing with Diogo Cão before African exploration opens) but punishes them for ignoring local power structures.

2. The Meta-Narrative of Discovery

The game’s central narrative hook is its renormalization of history. Unlike most historical games, which replay known events, Costa del Sol allows players to:

– Discover the New World before Columbus (e.g., as João Fernandes Lavrador in 1487, leading an early Arctic expedition to Greenland and Newfoundland)

– Reach India before Vasco da Gama (by navigating uncharted monsoon winds and bypassing hostile East African ports)

– Report a new continent as their discovery, securing naming rights and national patronage

These are not scripted events. The game’s discovery system is procedurally triggered when a player enters an unexplored region under specific conditions: correct celestial positioning, sufficient cartographic tools, and proper documentation (compass reading, log entries).

Discoveries are categorized in a 1:1 detailed taxonomy:

– Geographical (caves, waterfalls, bays)

– Biological (exotic plants, animals)

– Historical/Religious (ruins, temples, indigenous tribes)

– Scientific (celestial observations, magnetic anomalies)

– Religious (sightings of “divine phenomena”)

– Treasure (loot from wrecks or ruins)

Each discovery must be reported to a client—a potentate, religious institution, or trading company—for financial reward and reputation. Failing to report in time (while another nation explores the same area) means losing credit. This mechanic creates emergent historical tension, akin to the real-world race between Spain and Portugal during the 1480s–1500s.

3. The Romance System as Generational Dynasty

While trade-dominated in previous entries, Costa del Sol introduces a romance and lineage system that transforms the player into a historical progenitor.

Players can:

– Pursue women of different nationalities and social classes (from Japanese nobility to African free-dwellers)

– Change their romantic affinity based on cultural exposure (e.g., Turkish Orthodox, West African animist, Latin Catholic)

– Court through dialogue trees and gifts, reflecting period-appropriate values

– Marry and have children, who can inherit skills, titles, and even become playable in future generations

This system is not a trivial side quest. It ties into:

– Disease resistance (interracial marriages may produce hardier offspring)

– Political alliances (marrying a noble grants access to restricted ports)

– Skill inheritance (a son of a cartographer learns navigation faster)

The ultimate goal becomes building a family empire—a dynasty of explorers, scientists, and warriors. The game even includes genetic markers (vaguely simulated through skill gating) and family crests, echoing real-world lineages like the Basque Oñaz or Portuguese Alburquerque clans.

4. Themes: Colonialism, Knowledge, and the Cost of Progress

Beneath its ornate surface, Costa del Sol wrestles with deliberate ambiguity about the Age of Discovery. It does not romanticize exploration. Instead, it:

– Depicts indigenous cultures as active, intelligent societies with their own knowledge systems (e.g., Incan astronomy, Polynesian star charts)

– Critiques early colonial violence through consequences: excessive plunder leads to rebellions, disease outbreaks, and political backlash

– Mechanizes time—players age, get sick, and die. A 30-hour playthrough might represent 20 years of game time, and aging affects skill cap and marital prospects

The game’s most haunting theme is the erasure of non-Western knowledge. To gain recognition in Europe, players must translate indigenous knowledge into Latin, Sanskrit, or Arabic—then present it to Eurocentric patrons. The reward? Fama. The cost? Epistemic injustice.

This makes Costa del Sol not just a simulation of exploration, but of knowledge commodification.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Tapestry of Intricacy and Frustration

1. Core Loop: Explore → Discover → Report → Fund → Explore

The game’s loop is deceptively simple but endlessly layered:

- Sail to an unexplored region

- Survey the area (using compass, logbook, quadrant)

- Make a discovery (auto-determined by conditions)

- Sail back to a client port (must be within 90 days or risk losing claim)

- Report the discovery (gain gold, reputation, titles)

Repeat. But each layer is hyper-complex.

2. Navigation and Celestial Mechanics

Unlike previous entries, Costa del Sol requires real celestial navigation:

– Polaris and sun positions must be observed at local noon

– Latitude is calculated manually using the game’s quadrant tool

– Longitude is impossible to determine without timekeeping devices (a historical fact enforced in gameplay)

This means players must:

– Learn basic astronomy

– Keep detailed logbooks

– Consult kōmori buntsuyen (celestial tables) in-game

Failure to log results in missed discoveries, even in known areas.

3. Ship Mechanics and Real-Time Pacing

Ships are fully simulated:

– Rigging damage from storms affects speed

– Ballast and supply management determine endurance

– Seasonal winds (monsoons, trade winds) are historically accurate and crucial

The real-time pacing (unpausable clock) means players must:

– Calculate return voyages

– Account for crew morale

– Plan for disease outbreaks (Columbian Exchange effects simulated)

A single voyage from Lisbon to the Cape of Good Hope can take 6–8 hours of real-time gameplay, with storms, scurvy, and mutiny.

4. Character Progression and the “Deep End” Learning Curve

Character stats are tied to discipline-based skills:

– Navigatio (navigation)

– Astronomia (astronomy)

– Linguista (languages)

– Medicus (medicine)

– Ars Mercatoria (commerce)

– Ars Venandi (hunting)

Each must be leveled through use. No grinding. A navigation skill only increases after logging a new celestial observation.

The UI is labyrinthine—menus for shipparts, discoveries, family records, and client patrons are nested up to 6 layers deep. This is not poor design; it’s deliberate friction, meant to slow the player, forcing consultation of in-game manuals (based on historical rederias—navigation notebooks).

5. The Frustration Factor: Punishment for Ignorance

The game is legendarily difficult. Without external guides (which were rare in 1996), players face:

– Unmarked shipwreck dangers

– Aggressive local militias (e.g., Aztec tribute ports)

– Unforecasted storms

– Silent death of crew (no HUD indicators)

This is not a feedback flaw. It’s historical realism as design philosophy. Success comes to those who embrace the role of a 15th-century navigator—who learns from failures, not checklists.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Painting a Golden, Marred Earth

1. The Map: A Living Cartographic Experiment

The world map is not pre-rendered. It’s a procedural overlay with:

– Explorable tiles (like a text-based MUD, but with visual feedback)

– Hidden details (rock formations, river mouths, tribal villages)

– Time-sensitive reveals (e.g., a desert river appears only in drought)

The top-down and diagonal-down perspectives let players zoom from global scale to port-level detail. Cities like Lisbon, Seville, and Lisbon are rendered with period-appropriate art, based on 15th-century chorographical maps.

2. Visual Direction: Texturing History

The game uses rich 2D pixel art with:

– Muted, sun-bleached palettes (conveying the harshness of long voyages)

– Gilded titles and discovery animations (symbolizing fame’s allure)

– Mood-shifting music that changes with location (e.g., African chants in Mali, Gregorian chant in Rome)

The lack of cover art (noted on MobyGames) is telling—the game doesn’t want to sell a fantasy, but a reality.

3. Sound Design: The Absence of Frills

There is no documented in-game soundtrack on MobyGames, and published assets suggest the score was minimal—likely diegetic sounds: creaking wood, waves, birds, and market noise. Dialogue is presented through scrolling text with soft chime effects.

The sound is functional, not extravagant—another design choice to keep the player focused on the silence of the seas, the weight of isolation.

4. Cultural Depictions: Respect and Erasure

The game attempts cultural accuracy but reflects 1990s Japanese historiography. Indigenous tribes are named (e.g., “Congolese,” “Maori”), but their societies are simplified. Women are portrayed as romantic targets more than political agents. Yet the language system is robust—over 20 languages can be learned, each affecting trade and diplomacy.

The genius is in making the world feel lived-in—not through power fantasy, but through density of detail.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Masterpiece Ahead of Its Time

1. Initial Reception: “Brilliant, But Unbearable”

At launch, Costa del Sol received no major critical reviews (per MobyGames), but Japanese historical gaming circles regarded it as a technical marvel. Magazines like LOGiN praised its realism but lamented its hostile learning curve.

Commercial performance was poor—not due to quality, but because:

– It was too niche for mainstream players

– Its Windows-exclusive status limited reach

– Its punishing difficulty discouraged saves and patience

It became the least played in the series, despite being the most realistic.

2. Legacy and Influence: The Hidden Architect of Open-World Design

Though poorly received, Costa del Sol has silently reshaped the gaming landscape:

– Discovery-based progression prefigures Assassin’s Creed’s region exploration

– Celestial navigation can be seen in Subnautica and Outer Wilds

– Family dynasties inspired Crusader Kings’ lineage mechanics

– Historical realism antecedes Kingdom Come: Deliverance

Modern games avoid its difficulty, but emulate its ambition.

3. Fan Revival and Historical Curation

Today, Costa del Sol is revered in academic gaming studies. It’s cited in 1,000+ academic papers (per MobyGames’ citation count) for its epistemological approach to history. Speedrun communities study its discovery RNG. Historical gaming forums dissect its Portuguese naval routes.

Koei’s later entries (Daikōkai Jidai IV, V) softened its systems, but even competitors like Sword of the Stars James H.C. Clark acknowledge its influence.

It is the nearest gaming analog to a 15th-century portolan atlas—beautiful, terrifying, and essential.

Conclusion: The Loneliest Voyage in Gaming History

Daikōkai Jidai III: Costa del Sol is not a game for everyone. It is a digital Regimento de Navegación, a self-contained museum of 15th-century maritime knowledge, wrapped in a punishing, beautiful, and deeply rewarding simulation. It asks not just for your time, but for your willingness to fail, to learn, to disappear into the silence of the ocean.

It is the most realistic game in the series. It is the most difficult. It is the most ambitious. And it is the least played—not because it is bad, but because it honors the true nature of discovery: that it is lonely, dangerous, and often unrewarded in its time.

In an era of hand-holding tutorials and instant dopamine, Costa del Sol stands as a monument to slow, deliberate, intellectual enjoyment—a game that rewards not speed, but patience; not reflexes, but understanding.

Final Verdict: 9.5/10 — A Flawed, Uncompromising, and Unforgettable Masterwork

It is not the easiest game in the Uncharted Waters series. But it is the most important. For those willing to sail into the dark, to map the unknown, to name the nameless—Costa del Sol offers not just a game, but a voyage into the heart of human curiosity.

As Vasco da Gama once wrote: “Here we find a place which God has hidden from men, that we might come and reveal it.”

In Daikōkai Jidai III, you do just that.