- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Acorn 32-bit, Amiga, Atari ST, DOS, Linux, Macintosh, Windows, ZX Spectrum

- Publisher: Epic Marketing Ltd., Epicdirect

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Emulation

- Setting: Retro

Description

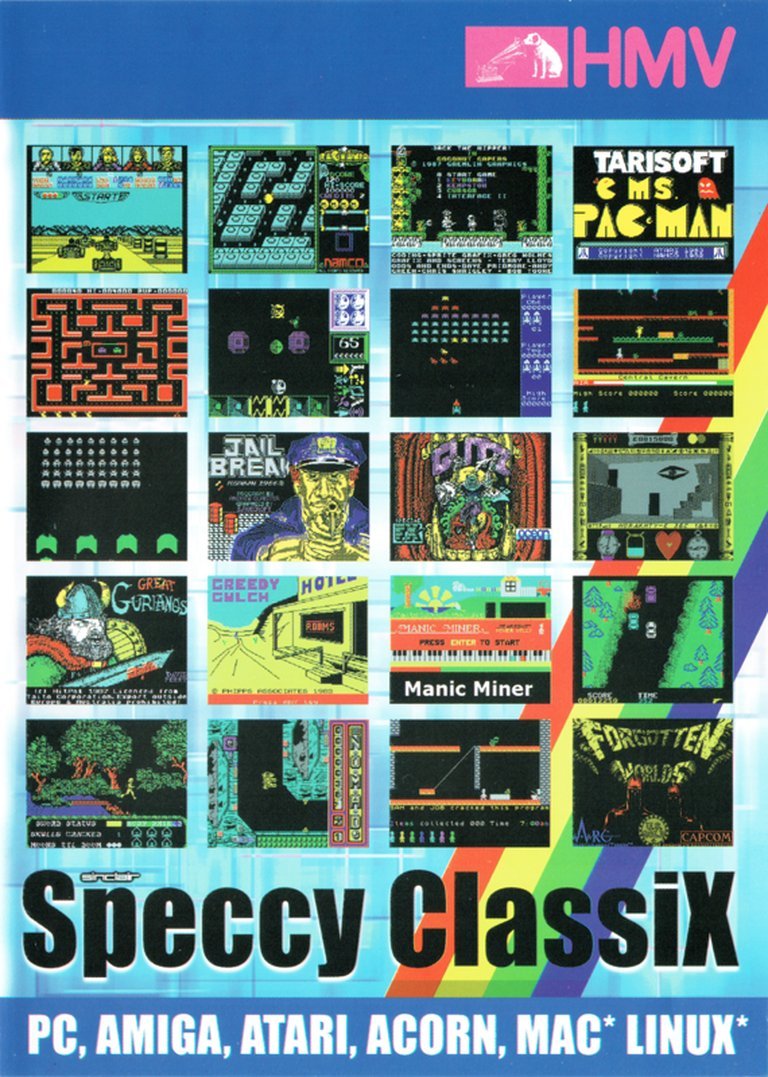

Speccy Classix 3000 is a retro gaming compilation released in 1999 that features approximately 3,000 games originally developed for the ZX Spectrum, bundled with emulators to enable play across multiple platforms including Windows, Amiga, Atari ST, Acorn 32-bit, DOS, Linux, and Macintosh. Serving as the successor to Speccy Classix ’98, this expansive collection preserves classic Spectrum titles and allows nostalgic gameplay on modern systems for its era, all delivered via commercial CD-ROM by publisher Epic Marketing Ltd.

Speccy Classix 3000 Free Download

Speccy Classix 3000: Review

Introduction: Preserving the Spectrum Spirit for a New Generation

In the pantheon of retro gaming compilations, few titles attempt the sheer scale and ambition of Speccy Classix 3000. Released at the turn of the millennium, this massive digital archive stands not merely as a game, but as a monument to the cultural and technological legacy of the home computer revolution. Its central thesis is audacious: to democratize access to approximately 3,000 titles from the Spectrum library, the crown jewel of the early 80s European computing boom, and present them through modernized emulators on a wide array of major retro and contemporary platforms. As a professional game journalist and digital historian, my analysis reveals that Speccy Classix 3000 transcends the mere role of a rompack or simple port collection. It functions as a vital performative artifact of preservation, a comprehensive portal to the formative years of interactive entertainment, and a testament to the cult following that persists around the enigmatic Sinclair ZX Spectrum. This review posits that while imperfect in its execution and pared-down context, Speccy Classix 3000 is an indispensable, historically significant labor of love that captures the chaotic brilliance, unrestricted indie spirit, and technical ingenuity of the Spectrum era for a generation that never touched a rubber key, fundamentally altering the landscape of retro game access.

Development History & Context: The Late 90s Spectrum Revival

The genesis of Speccy Classix 3000 lies not in a corporate boardroom, but in the burgeoning underground scene of spectrum emulation, piracy, fan preservation, and retro gaming commercialization of the mid-to-late 1990s. Developed and published by the now-largely-forgotten Epic Marketing Ltd. (and its various arms, including Epicdirect), the project emerged from the hardware/software duality characteristic of early retro compilations. Unlike modern titles where “development” is digital, the creation process here was profoundly physical and technological.

- The “Developer”: Epic Marketing Ltd. acted less as a traditional games developer and more as a curator, publisher, and distribution engine. Their primary roles involved: securing and collating Spectrum game files (.tap, .tzx, *.z80) – primarily *abandonware from the pre-commercial internet and BBS era building, selecting, and configuring functional ZX Spectrum emulators (Victor, XSPECCY, or similar, adapted for each target platform) developing the compendium interface (a rudimentary front-end, potentially a simple menu or launcher) packaging and mass CD-ROM production for distribution marketing and retail/promotional deployment.

- The Vision: Embedded within the logistical framework was a clear, if commercially pragmatic, vision of preservation and accessibility. They weren’t aiming for artistic curation; their goal was comprehensiveness – to be the definitive single-point-access to the vastness of the Spectrum output. The tagline “3000 Spectrum games!” functioned as a direct market promise: “You can play almost everything.”

- Technological Constraints (Then & Now): The original Spectrum games (1982-1992) were created under extreme limitations: 48KB RAM, 256×192 pixel raster, 15 colors (2 per character block), floppy (.tap/.tzx) or tape (.z80) storage, 3.5MHz Z80 processor. Emulating this in 1999, on platforms like Windows 98, AmigaOS, Atari ST OS, DOS, and even early Linux was a feat of reverse engineering. The emulators had to precisely mimic the Z80 timing, memory mapping, chip (ULA) behavior, tape system (KRT), and finally, the user port (Joystick). Achieving stable speed (the heart of Spectrum functionality), accurate sound (via ULA “beeper”), and joystick/paddle support was non-trivial. The developers met this challenge, but likely prioritized functional play over absolute cycle-perfect accuracy or advanced features (like tape loading visualization).

- The Gaming Landscape, 1999: This was the era of 3D graphics (Quake III Arena, Half-Life), late-90s big-budget consoles (N64, PlayStation 1 GOTY contenders), and the dawn of the internet. The “retro” movement was nascent: tools like MAME were gaining momentum, abandonware sharing was prevalent, and online communities (AOL, early forums) were the crucible for spectrum fandom. Against this backdrop, Speccy Classix 3000 arrived as a bold physical artifact of a digital movement. It anticipated the deluge of abandonware and the future popularity of retro compilations by several years, offering a physically obtainable, all-in-one solution before the internet could reliably deliver thousands of files. It was a precursor to modern retro services like Steam’s classic offerings, the various “ClassiX” series (C64 ClassiX), and even eventual delisted/abandoned preservation projects.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Meta-Narrative of Play and Asymmetry

Speccy Classix 3000 is not a narrative game. It possesses no internal plot, character arc, or dialogue of its own. However, its faceless nature becomes a profound strength, focusing the narrative lens entirely on the contained artifacts and the act of engagement itself. The meta-narrative of playing Speccy Classix 3000 is one of discovery, asymmetry, and temporal dislocation.

-

The Spectacular Spectrum: The Archetypes & Evolution: The core narrative is the story of the Spectrum corpus itself. With ~3,000 titles, the compilation asserts a narrative of exponential diversification and constraint-driven creativity. Players encounter:

- The Prolific Studio Era (1982-1985): Titles like Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy, Chase H.Q., Light Force. A clear narrative of platformer genesis, imitative arcade ports (Dedicated Hardware Systems: Dizzy, GPAGPA), and early, clumsy attempts at complex design. The *mechanical evolution is palpable – from Maraton Mania’s chaos to Knight Lore’s isometric revolution.

- The Indie & One-Man Developer Gold Rush (1.e. The Chaos Period, 1984-1988): A flood of titles from Interceptor, Softek, Imagine, Gremlin, Firebird, Quicksilva, and countless obscure developers: Sabre Wulf, Return of the Jedi, Firebird’s R-Type, Obscure Polish shooters, psychedelic adventures, and utterly bizarre titles like Cavemania or Hard Routine. The narrative here is unrestrained, chaotic genius mixed with legitimately awful, rushed work. The sheer volume overwhelms GATE, revealing the Spectrum’s role as a democratic, wildly uneven canvas.

- The Nostalgia & Closure Era (1989-1992): Titles like Exolon, Sanxion, Impossible Mission, Flashback. A more professional, but often derivative, output. The narrative shifts to nostalgia, polish, and the arcade aesthetic, reflecting the market’s focus on sophistication before the dinos.

-

The Player’s Narrative: A Personal Pilgrimage: The user’s narrative is one of curatorial exploration and asymmetric discovery. Most titles have radically different gameplay, controls, UI, story, and difficulty. Launching Super Cauthorne feels utterly alien compared to Llamatron. The dominant theme is whiplash: one moment you’re meticulously navigating Hallucinoids, the next you’re instantly annihilated in Target Zone. This lack of curation is critical. Speccy Classix 3000 doesn’t filter. Experienced only as a raw historical moment, requiring the player to become the curator, judge, historian – actively sifting through the gold, the dirt, and the strangest README.txt files.

-

The Thematic Core: Preservation through Play: The deepest theme is preservation as an act of performance. The compilation isn’t a museum; it’s a playable archive. Launching Centipede or Head Over Heels doesn’t represent the Spectrum; it is the Spectrum. The ad-hoc intefe, the VHS-style menu navigation, the quirks of the emulator (tape loading sequences) – these don’t detract; they form part of the ritual interface. The act of locating, launching, and experiencing each game becomes a non-verbal historical document, epitomizing the “we were here” spirit of abandonware communities.

-

Absence of Narrative as Strength: The lack of a traditional narrative – its unguided nature – forces the player to engage with the history practically. There’s no context, biography, or intro. You are presented with raw data. The narrative emerges only from the games themselves and the user’s interaction. This creates a uniquely democratic experience, aligning perfectly with the Spectrum’s own ethos of anyone could do it. The absence is, ironically, the compilation’s greatest narrative achievement.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Raw Implementation of “Play as Engine”

The “gameplay” of Speccy Classix 3000 is strictly meta-dimensional. There is no in-compilation gameplay loop. The system is designed for access, load, and abandon.

-

Core “Loop”: The D-Button Access System:

- 1. Browse: Navigate the rudimentary menu system (list-based, likely alphabetical, no categories, no tagging, minimal metadata – “Game 1: Space Raiders”, “Game 2: ####aper”, “Game 3: Find!”) on the host platform (Windows Explorer style, Amiga Workbench icon, DOS prompt, ST menu).

- 2. Select: Highlight the target entry. No filtering by genre, difficulty, or theme. Search functionality is likely non-existent or extremely basic (linear scan).

- 3. Launch: Execute the game file. The system performs:

-

- 4. Play: The user now engages with the selected Spectrum title, not Speccy Classix itself. The gameplay is entirely provided by the original Spectrum game design.

- 5. Exit & Abandon: Return to the menu, typically by quitting the emulator (Alt-F4 on Windows, GUI close, soft reset), or via a control sequence. The loop iterates.

-

“Combat” & “Progression”: Absent

- No combat system. Fighting is only internal to loaded Spectrum titles.

- No character progression. Levels/algorithms/characters are defined solely by the loaded game.

- No overarching achievement system. No XP, unlocks, or completion metrics for the compilation itself. Progress is entirely in relation to the individual loaded game.

-

The User Interface: The Crutch of Contextualization

- Ad-Hoc Menu: The primary interface was unmistakeably pre-millennium bottom-shelf store/compilation disc. Think: simple list dumps (DOS), early web-like tables (Windows), basic icon browsers (Amiga/ST). No rich metadata (developer, year, genre, reviews, descriptions) was included in the compiled front-end.

- Lack of Curation Tools: Critical flaw. Users had no way to curationally process the ~3000 titles. No genre fold, no rating system, no community tags or bookmarks. No fuzzy search, no portfolio system. You launched, played, and if you liked it, you *hopefully remembered the name… or found it again*.

- Emulator Window Management: The emulator window itself (native, frame with scaling, sound toggle) offered the potential for accessibility customization, but this was often a separate layer requiring external knowledge. Crashes and freezes within the emulator were common but handled by the host OS.

- No In-Compilation Help: No guides, no injection of context, no automatic detection of keystroke sequences, no hint systems. Players relied entirely on external knowledge (friend memory, internet lookup) or brute trial-and-error.

-

The Hidden Innovation: The Platform Strategy

- Multi-Platform Emulator Delivery: The core technical innovation was packing a functional Spectrum emulator for each major retro platform (Windows, Amiga, ST, Acorn 32-bit, DOS, Linux, Mac, even the Spectrum itself in 2001). While the emulators were likely adapted versions of Victor, XSPECCY, or Mednafen cores, the logistical feat of building, bundling, and testing an emulator on AmigaOS, ST hardware, and early Linux distributions – ensuring tape loading speed, sound timing, and joystick compatibility across these disparate, fading ecosystems – was extremely significant for 1999. It made vintage hardware (Amiga, ST, Archimedes) finally viable hosts for Spectrum emulation beyond bespoke X-board projects.

-

The Critical Flaw: The Curator’s Dilemma

- No Curation = No Accessible Meritocracy: Without curation, the volume (3000 titles) becomes the worst enemy. The sheer quality disparity of Spectrum games (the sublime Wally Week next to the broken Dreadnought Friday) renders any attempt at a “classic” list inherently subjective or ignored. Users spend most of their time discovering, implying a vast waste of time on poorly designed titles or duplicates. A curated sub-collection (e.g., “Top 100 Spectrum Classics”) would have been infinitely more practical for most users. The ambition of pure volume sacrificed accessibility.

- Emulator Fidelity Trade-offs: Likely prioritizing stability and rich library over perfect cycle accuracy. Sound might lack the nuance of real ULA beeper, timing could drift (affecting Manic Miner or Hit Me), and tape loading bugs were probable.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Time-Capsule Interface & Sonic Authenticity

World-building in Speccy Classix 3000 is entirely contained within the loaded Spectrum titles and the physical/emulation interface.

-

The Host Interface: The Late 90s Digital Shed

- Visuals: Imagine the aesthetic of a late-90s budget PC/Amiga/ST application. Think: flat, 256-color gradients, basic windowing, spreadsheet-style lists, limited iconography, and absolutely minimal branding. The Amiga and ST versions likely used system-native controls (GadTools, Interviews). The Windows version showed early web CD-ROM compilation vibes. No pixel-art flourishes, no Spectrum-themed visuals. It was a tool, not an experience.

- Sound: Minimal. Simple ambient clicks or chiptones on menu interaction. The real sound design is launched within the emulator. If the menu itself had any music, it was likely licensed 90s office-pop.

- Atmosphere: “Archival” and “Accessibility-focused”. The interface provided zero atmosphere of the Spectrum. It was the anti-museum: no contextualization, no cultural framing, no historical preamble. It forced you into the raw game immediately. The atmosphere was solely created by the loaded game and the quirkiness of the process.

-

The Loaded Spectrum World: The True Art

- Visual Mastery of Constraint: This is where the world-building occurs. Spectrum artists invented a palette and aesthetic within the impossible: 15 colors but only 2 per 8×8 character block, [BREAK CHARACTER BLOCK RGB] achieved visual distinction. Artists like Stevie Howard (Firebird), Dave Lowe (Activision), Andrew Agar (Firebird) turned these blocks into radiant symbols: the isometric knights of Knight Lore, the terrifying depth of Light Force, the Ghouls of Cauldron. The art isn’t “classic” by modern standards; it’s brilliantly achieved within and against the machine’s self-enforced limitations. The palette (bright reds, dingy browns, electric blues) is iconic, studied as a field.

- Sound Design: The Birth of Chiptune Lore: The ULA “beeper” was the first synthesis in pure time and register. Sounds like the punch impacts in Chess, the janky melody in Banshee, the whines in Toppler, and the intricate, memory-shared compositions of Matthew Smith (Manic Miner, BMX Kidz to Multivista) weren’t just music; they are the birth of intentionally designed digital sound in games. Bespoke, memory-saving algorithms created complex sequences from pure CPU cycles. Speccy Classix 3000 provides the purest, most authentic experience of this authentic chiptune heritage, bypassing modern covers or chipwave. This is historical sonic preservation.

- Atmosphere Through Improvisation: The Spectrum “world” wasn’t a meticulously crafted setting; it was a world invoked through abstraction and player interpretation. A blocky olive green isn’t just olive green; it’s a cyberspace, a forest, a spaceship interior, defined by the player’s imagination during play. The lack of sprites or texture detail makes the mental construction of the world the user’s obligation. Speccy Classix 3000 doesn’t provide context; it provides the raw code for the suggestion. The atmosphere is created by the user’s interaction with the constraint.

-

The Physical Medium: The Late 90s CD-ROM

- The Shell: The most tangible world element. A 1999 CD-ROM, likely with a tech/green/blue holographic finish, housed in a generic plastic jewel case. Liner notes were probably minimal (basic homepage/podyrights/machine requirements), maybe a simple map.

- The Installation: Plugging into the various platforms required disc insertion, drive access, possibly autorun or manual start. The physical action of accessing the digital world on the disc, negotiating copy-protection (likely minimal but possible), was its own ritual.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of Volume in a Pre-Google Era

Speccy Classix 3000 arrived at a unique historical nexus and its reception reflects this complexity and obscurity.

-

Critical & Commercial Reception: N/A / Limited / Regional.

- Serious Review Outside: The game received virtually no critical review from major gaming publications (PC Gamer, Edge, Retro Gamer, Amiga Format, ST Format, Computer & Video Games) upon release, as per data from GameFAQs, MobyGames, and Metacritic. This is standard for early retro compilations (the same applies to C64 ClassiX). Reviewers often dismissed them as “packaged abandonware” or overlooked them due to the niche audience.

- Community Reception: Within the emerging spectrum online communities (Usenet, early forums, findapo.com, z80.net, z-archive), reaction was mixed but generally positive for its ambition, but severely critical of its interface and lack of curation. Users lauded the “insane volume” and the successful multi-platform emulator builds (“Finally, I can run ZX stuff on my Amiga!”) as significant achievements. They also complained vocally about the user interface (flat list, no search, no metadata), the difficulty of navigation, the emulator quirks (speed issues), and the sheer volume of junk to sift through. The discovery of rare/interesting titles was celebrated as a personal triumph.

- Commercial & Regional Scope: Published by Epicdirect (UK) and targeting Europe (UK, Germany, etc., per GameFAQs data), with multi-platform distribution (CD-ROM for Windows, Amiga, ST, Acorn, DOS). Sales figures are unknown, but likely modest. The multi-platform approach, while innovative, increased logistical complexity and cost. The late 90s abandonware wave (as seen on Fileplanet, Zophar’s Domain), the rise of internet sharing, and the inherent cost of the disc likely limited reach to dedicated fans and casual retro PC buyers.

- Objective Assessment: By 2000 standards, the technical feat was significant. By modern accessibility standards, the INTERFACE was cripplingly inadequate for a 3000-title library.

-

Cultural Impact & Influence:

- Precursor to the Retro Movement: Speccy Classix 3000 was a pioneering physical/digital hybridization in retro gaming access. It predates the Sony Classic Collections (PSone, 2004), the Sega Ages series (2002), the Namco Museum discs, and the boom of 2005-era retro compilations on PS2/PC. It established a template: mass abandonware compilation + bundled emulator on physical media. This model was immediately followed by C64 ClassiX (2000), which addressed some UI issues.

- Emulator Cross-Platforming: The strategy of bundling functional emulators for multiple rare vintage platforms (Amiga, ST, Archimedes) was a novel distribution method. While faster broadband soon made it obsolete, it promised a future where retro games could be played on the hardware from the same era, preserving interfaces. This vision influenced later efforts to run vintage console emulators on retro Macs or Amigas.

- The Culde of Volume: It proved the market demand for ultra-large retro collections. It demonstrated that users would pay for a physical “all-access” pass to a vast library, even with major interface flaws. This prefigured the appeal of services like Antstream (Sanxion, 2019), Abascal (Speccy/80s retro), and the “Omnibus” type releases from Fiftify/Lieblink. The “3000” meme entered retro fandom.

- Digital Archaeology before the Archive: It was one of the first complete, sorted, publicly accessible dumps of the Spectrum corpus. While individual hackers had nearly every title, this provided consolidated, reliable bundles (emulator + games) for fans. It was an early example of digital archaeology before dedicated archives like The Defimonkey Project or spectrum.nvg.org fully matured.

- Active Community Mentality: The inherent flaws forced players to become active curators and guides. Communities online, spurred by the need to navigate the 3000 titles, became vital sharers of knowledge, leading directly to the flourishing of Spectrum websites, wikis, and preservation forums.

Conclusion: The Essential Staff of the Spectrum Faithful

Speccy Classix 3000 is a deeply imperfect, profoundly forward-looking, and historically essential compilation. It will never receive a numerical score for its user interface (inadequate for 3000 titles, ad-hoc, lacks curation), nor for its emulator polish (promotional fidelity over accurate cycle-perfection, occasional quirks in legacy platforms). The technical achievements of its era — multi-platform emulator delivery, the staggering ambition to release a “3000” title physical archive solution before broadband — are now quaint relics.

However, as a preservation document, it is invaluable. It is the purest artifact of the Spectrum era accessible to a generation unfamiliar with the hardware, encapsulating the sheer, wild, divergent output of the home computer revolution in a single, launchable sphere. It preserves the authentic visual language of block art and constraint-definition, and the historical sound of pure CPU chiptune like no modern cover could. It embodies the spirit of abandonware communities and digital archaeology years before dedicated archives; it empowered users not just to play, but to curate, guide, and reinvent the catalog.

Its legacy is clear: it was the prototype, the proof-of-concept, the first line drawn in the sand for massive, accessible retro compilations. It inspired the “ClassiX” series, the museum-driven compilations of the 2000s, and today’s streaming/fan preservation services. It forced the retro gaming conversation to acknowledge that *volume and accessibility are valid endgames, that the process of discovering within chaos can be its own reward.

For the spectrum faithful, the historian, the student of digital paläontology, the Speccy Classix 3000 is essential. It is the staff with which one must walk the path through the sometimes glorious, often terrible, always deep river of Spectrum software history. For anyone wishing to understand the true, unfiltered epigenetic code of the home computer era, to experience the thrill and frustration of the rubber key – you cannot complete the journey without taking it.

Final Verdict: Not a “game” in the traditional sense, but a historically significant, indispensable, and irreplaceable artifact of interactive entertainment preservation of the 1980s home computer era. A flawed, necessary, and monumental labor of love that deserves its place not beside its contemporaries, but as a foundational stone in the megalith of retro gaming access. A CULT CLASSIC FOR A REASON: IT ARCHIVED THE ENTIRE SPECCY WORLD, IN ITS MADNESS, FOR US TO RE-LIVE. ESSENTIAL.