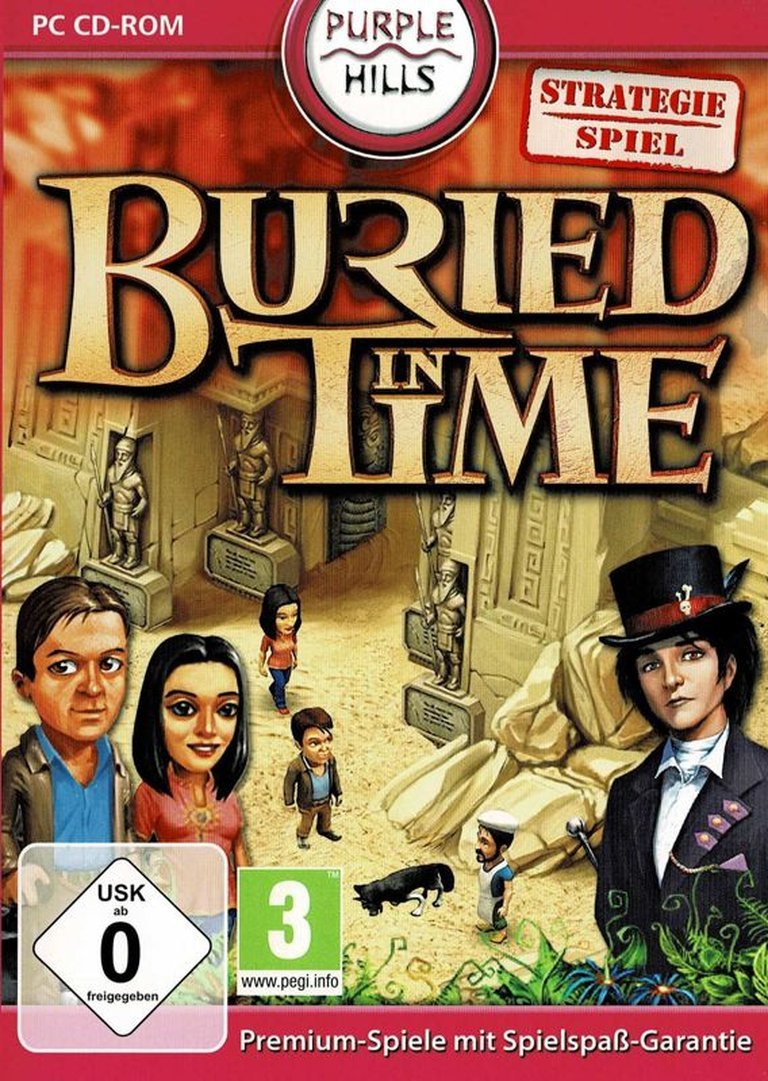

- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH

- Developer: I-play

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Classical antiquity

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

In ‘Buried in Time’, players step into the shoes of Agent #5, a time-travelling operative from the Temporal Security Agency, who must clear his name by gathering evidence across seven meticulously researched worlds. The game blends historical settings like Mayan catacombs and Leonardo da Vinci’s laboratory with futuristic locales such as a derelict space station, creating a nonlinear cinematic adventure where players solve puzzles, explore detailed environments, and uncover a complex, logically consistent story.

Gameplay Videos

Buried in Time Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com (80/100): Buried in Time is a potentially great sim game with a serious design flaw.

pibweb.com : If you dislike dying in a game, you should avoid this one. Death is fairly common and easily achieved.

Buried in Time: Review

Introduction

In the vast and often-overlooked landscape of video game history, certain titles stand not just as products of their time, but as ambitious, almost quixotic endeavors that push the boundaries of technology and narrative. Such is the case with the two, seemingly disparate, titles that share the name Buried in Time. One is a celebrated, cinematic science fiction adventure from the mid-1990s, lauded for its complex plot and groundbreaking fusion of live-action and computer-generated graphics. The other is a resource management puzzle game from the 2010s, remembered for its charming story but critically marred by a significant design flaw. This dual nature of the name presents a fascinating opportunity for analysis. It forces us to ask: what makes a game endure, and what causes it to be relegated to the dustbin of history? Through a meticulous examination of both the Presto Studios masterpiece and the I-play title, we can dissect the anatomy of success and failure. My thesis is that while both games share a title and a theme of exploration, their legacies are defined by their core fundamentals: The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time succeeded by integrating its ambitious technology into a compelling, logical narrative, creating an experience that felt like a playable movie, whereas the I-play Buried in Time failed to deliver on its potential due to fatal gameplay design oversights that broke its otherwise charming simulation.

Development History & Context

The story of Buried in Time is, in itself, a tale of two vastly different development philosophies and eras.

The Presto Studios Masterpiece: A Cinematic Vision

Developed by Presto Studios and published by Sanctuary Woods in 1995, The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time emerged from the fertile ground of the Macintosh gaming scene, alongside contemporaries like Myst. The studio, helmed by president and director Michel Kripalani, creative director Phil Saunders, and writer David Flanagan, harbored a singular, ambitious goal: to create a “total cinematic experience.” This was a radical departure from the first Journeyman Project, which had established the template but lacked a defined personality for its protagonist. For the sequel, the team sought to craft a rich, nonlinear storyline that unfolded “like a page-turning science fiction novel” and a “page-turning science fiction novel.”

The technological constraints of the era were both a challenge and a catalyst for innovation. The game was a massive undertaking, spanning three CD-ROMs to accommodate its vast array of pre-rendered 3D environments. The development process was meticulous and labor-intensive. Saunders, leveraging his experience as an industrial designer for Nissan Automotive, applied his skills to historical research, meticulously recreating settings like the 13th-century Château Gaillard (based on Richard the Lionheart’s actual stronghold) and Leonardo da Vinci’s studio. This research was paired with pure imagination for the futuristic locales. The team produced over 500 hand-drawn sketches, which were then used to create 3D computer models, complete with texture maps for every surface. These models were assembled and lit by artists, and the final scenes were rendered frame by frame, with each of the game’s more than 25,000 frames taking approximately 20 minutes to generate. This painstaking process resulted in stunning, photorealistic backdrops that were leagues beyond most games of the time.

To populate these digital sets, Presto Studios turned to Hollywood. They enlisted professional actors, including Michelle Scarabelli of Alien Nation and Star Trek: The Next Generation, and commissioned a specialized vacuform plastic biosuit from All Effects Group, a film industry special-effects company. The actors were filmed against a blue chroma screen, a technique that presented a significant technical hurdle: seamlessly integrating live-action footage with pre-rendered 3D backgrounds required precise matching of camera angles, perspective, and lighting. The final component was a professional score and sound design by musician Bob Stewart, whose goal was to create effects that were “so accurate as to be transparent,” enhancing the drama and realism. This fusion of film production techniques and game development created an experience that felt genuinely high-budget and cinematic.

The I-play Simulation: A Casual Conundrum

In stark contrast, the 2012 Buried in Time from developer I-play exists in a completely different universe. This game is a product of the casual gaming boom, a time when digital distribution platforms like Big Fish Games flourished, and gameplay was often streamlined for accessible, bite-sized sessions. The game, published by S.A.D. Software, was designed as a “Puzzle Adventure Game” with a clear emphasis on resource management and simulation mechanics. Its development context was that of a smaller, mobile-focused studio creating content for a mass market. The technological constraints were not about rendering 3D worlds on multiple CDs, but about creating an efficient, engaging experience that could run on a wide range of consumer PCs. The ambition was not cinematic grandeur but charming, accessible fun, a simpler tale of archaeologists uncovering a lost jewel in a peaceful kingdom.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative frameworks of the two Buried in Time titles reveal their core identities: one is a complex, time-bending thriller, while the other is a heartfelt, linear fable.

The Journeyman Project: A Web of Time and Betrayal

The narrative of The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time is a masterclass in sci-fi storytelling, characterized by its nonlinearity and intricate plotting. The game opens in 2318, six months after the events of the first game, introducing Gage Blackwood (Agent 5) as a fully realized character. The inciting incident is brilliant and immediately engaging: a future version of Gage appears to his past self, warning that he has been framed for tampering with history. This sets up a compelling mystery and a personal quest for exoneration. The stakes are raised exponentially as the Symbiotry of Peaceful Beings considers revoking Earth’s monopoly on time travel, threatening the very existence of the Temporal Security Agency (TSA).

As Gage, the player is joined by Arthur, a witty and helpful AI companion who provides both exposition and comic relief. The story unfolds across seven intensely researched “time zones,” including the Mayan catacombs of Chichen Itza, the workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, and the besieged Château Gaillard. Each location is not just a backdrop but a character in the narrative, filled with period-specific detail and clues. The plot is a web of intrigue, eventually revealing the culprit to be Michelle Visard, a fellow TSA agent. This betrayal is further complicated when it’s discovered that an alien race, the Krynn, are the true masterminds, manipulating events to further their own interests. The story culminates in a dramatic sacrifice from Arthur and a final confrontation that saves Gage’s future self. The themes are mature and thought-provoking: the ethics of time travel, the nature of identity, and the political implications of advanced technology are all explored with a surprising amount of depth for a video game. The dialogue, while functional, serves the plot effectively, and the addition of professional actors gives the characters a weight that was absent in the series’ debut.

The I-play Adventure: A Fable of Love and Loss

The I-play Buried in Time takes a completely different thematic approach, focusing on a timeless story of love, loss, and redemption. The narrative is far simpler and more traditional. The game is set in motion by the tragedy of a great ruler who gave a sacred jewel to a beautiful queen, an act of love that, upon her inexplicable death, plunged a kingdom into ruin. Centuries later, two young archaeologists, Bingham and Jack, arrive to uncover the lost jewel and the secrets behind the kingdom’s fall.

The story is presented as a charming “tale,” with a clear moral that “the greatest riches are those that come from the heart.” It lacks the complex, interwoven plot of its namesake, instead opting for a straightforward journey of discovery. The characters are archetypes—the earnest archaeologists, the mysterious locals—and the dialogue serves to advance a simple, emotional story rather than a convoluted mystery. The themes are universal and accessible: the search for treasure, the uncovering of history, and the power of pure intentions. While not nearly as narratively ambitious as the Presto title, the I-play game’s story is its strongest asset, providing a warm and engaging framework for its gameplay simulation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Here, the two games diverge most dramatically, with one offering a refined, albeit challenging, adventure experience, and the other succumbing to a critical flaw that undermines its entire design.

The Journeyman Project: Precision Puzzle-Solving

The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time is a first-person point-and-click adventure game. The core gameplay loop involves exploring static, pre-rendered environments, interacting with objects, and solving environmental and inventory-based puzzles. A significant improvement over the original game is the implementation of “smooth movement,” which replaced the awkward “jumping” between nodes, making navigation far more intuitive. The player’s primary interface is the advanced Pegasus suit, which is controlled via various “biochips.” These chips provide functions like analyzing objects, accessing a hint system, and communicating with Arthur.

The puzzles are the heart of the experience and are largely lauded for their logical integration into the world. They require careful observation, pattern recognition, and the occasional transport of an item from one time period to another. The game introduces a clever risk/reward element: the player’s actions can have dire consequences. As one review noted, “Death is fairly common and easily achieved. Getting through the game without dying would be almost impossible.” This creates a constant tension, forcing the player to think carefully before interacting. The game offered two difficulty levels, “adventure” and “walkthrough,” to cater to different player skill levels. The interface, while praised for its cinematic presentation, was also criticized by some for being “elaborate” and “unwieldy,” with a small viewscreen that made it difficult to spot crucial details.

The I-play Simulation: A Fatal Flaw in the System

The I-play Buried in Time is a resource management and puzzle game with a heavy simulation component. The player manages a team of archaeologists at a dig site, assigning them to various tasks based on their specific skills: surveying, excavating, brushing, analyzing, and cooking. The goal is to uncover artifacts, manage resources like money and food, and solve puzzles to progress the story. There is a satisfying RPG-like element in that characters can increase their skills over time with experience. The game also features unexpected events and dialogue between characters, adding a layer of personality to the simulation.

However, the entire experience is built on a foundation of sand, undermined by a catastrophic design flaw. As Gamezebo’s review powerfully illustrates, it is entirely possible for the player to get “stuck” with no recourse but to restart the game from the very beginning. This can happen, for example, if the player’s only cook character becomes unavailable (by falling down a well, for instance), and the player lacks the funds to hire a new one. The game creates a scenario where all characters become too hungry to work, and the player has no way to earn more money—upgrades are too expensive, and there is no option to sell items. The developers confirmed this flaw, stating, Buried in Time has to be started all over again from the very beginning.” This single, unforgivable mistake completely breaks the game’s promise of a continuous adventure and is a black mark on an otherwise promising concept.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Both games excel in creating immersive worlds, but they achieve this through vastly different artistic and technical means.

The Journeyman Project: Photorealism and Cinematic Flair

The world-building in The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time is its crowning achievement. The “total cinematic experience” was not just a marketing slogan; it was a design philosophy. The hand-drawn sketches, the painstaking 3D modeling, the professional texturing, and the 20-minute-per-frame rendering process all combined to create photorealistic environments that were breathtaking for their time. Each time zone, from the dusty Mayan catacombs to the pristine, high-tech Temporal Security Agency, is filled with minute, researched details that bring the world to life. This visual fidelity is complemented by the seamless integration of live-action FMV sequences. The use of professional actors in custom-made costumes, filmed against a blue screen and composited with the 3D backgrounds, was a technically audacious move that paid off spectacularly. The result is a world that feels tangible and believable.

The sound design, led by musician Bob Stewart, is equally impressive. The professional score and meticulously crafted sound effects work in harmony to build atmosphere and enhance the sense of realism. The sounds are not just loud noises; they are “transparent,” designed to feel like an organic part of the environment, making the player truly feel present in Gage’s world.

The I-play Adventure: Charming and Functional Aesthetics

The I-play Buried in Time adopts a completely different artistic style. Its world is one of bright, clean, and charming 2D graphics. The art style is functional and appealing, designed to be clear and easy on the eyes for a casual audience. The archaeological dig site is colorful and well-realized, and the character designs are simple but effective. While it lacks the photorealistic ambition of its namesake, it creates a pleasant and inviting atmosphere that suits its lighthearted story. The sound design and music are similarly serviceable, providing a pleasant backdrop to the resource management gameplay without ever stealing the spotlight. The art and sound work in concert to create a world that is more “charming” than “cinematic,” perfectly aligned with the game’s casual, simulation-focused goals.

Reception & Legacy

The legacies of these two games are polar opposites, a direct result of their critical reception and the long-term impact they had on the industry.

The Journeyman Project: Acclaimed and Influential

The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time was met with mostly positive reception upon its release. Critics were impressed by its ambition and execution. Just Adventure awarded it an “A+”, calling it “one of the best games I’ve ever played. It impressed me from start to finish.” While some, like Adventure Gamers, criticized the small viewscreen and unwieldy interface, the general consensus was that the game’s strengths far outweighed its flaws. It was praised for its “staggering” scope, clever puzzles, and state-of-the-art graphics.

Commercially, the game was a success. It sold over 225,000 units on a budget of “almost $500,000,” and the overall Journeyman Project series had sold roughly 500,000 units by July 1996. Its legacy is that of a technical innovator and a benchmark for cinematic adventure games. It demonstrated the potential of CD-ROM media for immersive storytelling and influenced developers to think bigger about the scope and presentation of their games. Its reputation has only grown over time, with Adventure Gamers naming it the 89th-best adventure game ever released in a 2011 retrospective, cementing its place in video game history as a flawed but ambitious classic.

The I-play Game: A Cautionary Tale

The I-play Buried in Time received a muted reception, largely overshadowed by its critical flaw. While its charming story and interesting simulation elements were noted, the game was remembered for its fatal design oversight. Gamezebo’s initial review gave it a failing grade, specifically because of the game-breaking bug that could force a player to restart. Although the developers later released a patch that addressed this specific scenario, the damage was done. The game is remembered not as a charming adventure, but as a cautionary tale about the importance of thorough quality assurance. Its legacy is one of wasted potential. It had no discernible influence on subsequent games, as its core mechanics were not unique enough to be worth replicating, and its failure served as a stark reminder that even the most charming story cannot save a game that is fundamentally broken.

Conclusion

In comparing the two games that bear the title Buried in Time, we are presented with a study in contrasts that illuminates the core principles of game design. The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time stands as a testament to the power of a cohesive artistic vision. Its ambition was not merely technological but narrative; every element, from the pre-rendered graphics to the Hollywood casting, was in service of a compelling, science-fiction story. Despite its user interface quirks and occasional harsh difficulty, it succeeded because its gameplay, world-building, and narrative reinforced one another, creating an experience that was greater than the sum of its parts.

Conversely, the I-play Buried in Time demonstrates that a charming narrative and an interesting premise are insufficient to guarantee a quality game. Its failure was not one of vision but of execution, a single, unforgivable design flaw that shattered the player’s trust and rendered hours of progress meaningless. This crucial difference highlights a fundamental truth: a game’s mechanics are its foundation. If that foundation is cracked, no amount of aesthetic polish or narrative charm can hold the structure together.

Ultimately, the dual legacy of Buried in Time serves as a permanent record in the archives of gaming history. One title, the Presto Studios masterpiece, is remembered as a flawed but ambitious pioneer that pushed the boundaries of what an adventure game could be. The other, the I-play simulation, is a forgotten relic, a cautionary footnote that reminds us that even the most alluring treasures can be worthless if they are built on a bedrock of sand.