- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: iPad, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, UnikGame

- Developer: UnikGame

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Falling block puzzle, Hidden object, Tile matching puzzle

- Setting: Fantasy, Medieval

Description

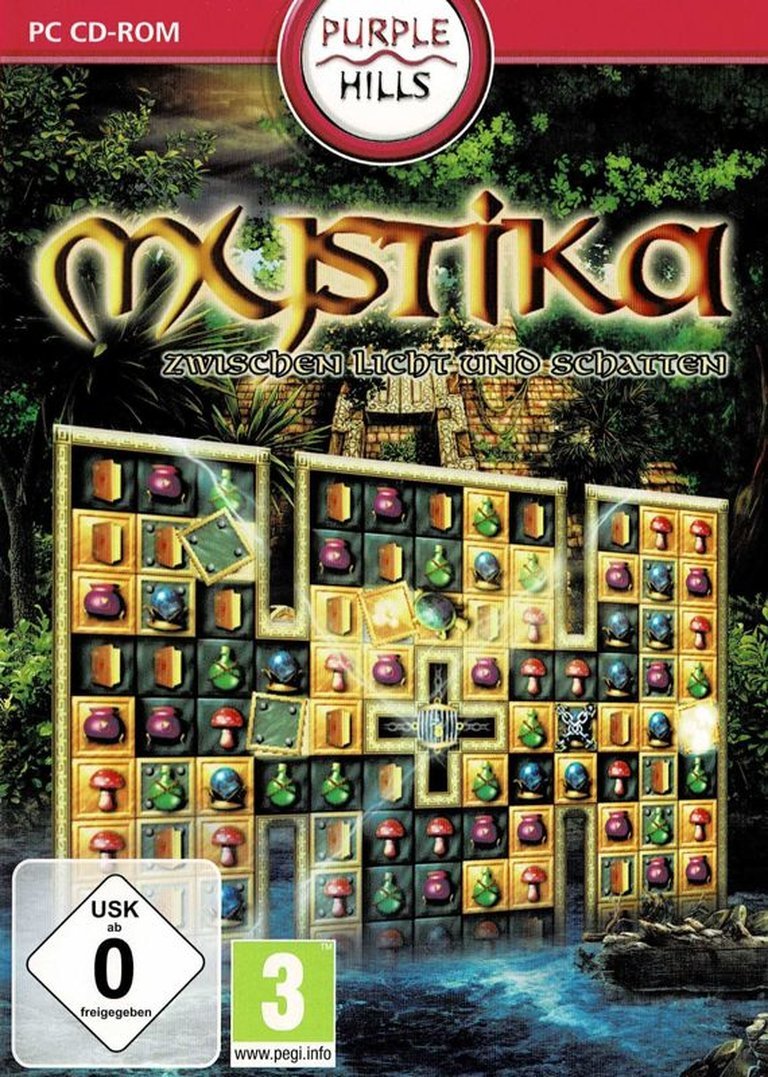

Mystika: Between Light and Shadow is a fantasy-themed match-three puzzle game where players must save the magical land of Lumina from the dark queen Tenebria. The game combines match-three gameplay with hidden object levels, featuring timed challenges, magical spells, and obstacles like steel plates and chained items. Players swap tiles to clear gold tiles, defeat creatures, and progress through a medieval setting filled with light and shadow.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Mystika: Between Light and Shadow: Review

Introduction

From the enchanting realms of Lumina to the shadow‑laden courts of the Dark World, Mystika: Between Light and Shadow asks a single question: can a lone hero restore balance to a world on the edge of ruin? Released by UnikGame in September 2012 for Windows, the title swiftly found a home in Big Fish Games’ library and later premiered on macOS, iPad, and mobile storefronts. As my thesis, I argue that while Mystika represents the quintessential late‑2010s casual puzzle franchise—imbuing a match‑three core with a story, hidden‑object side content, and novelty spells—it simultaneously illustrates the genre’s fragility: an elegant concept, limited depth, and a UI that can feel both familiar and frustrating. This review will unpack each facet—from development context to long‑term legacy—to assess what this game truly contributes to the wider tapestry of puzzle gaming.

Development History & Context

UnikGame, a small studio founded in Spain, specialized in match‑three titles for the casual PC niche. Their partnership with Big Fish Games (a dominant distribution platform for downloadable casual titles) exemplified the commercial strategy of that era: frequent sequels, incremental gameplay tweaks, and a focus on keeping cost and development time low. Mystika debuted on Windows in 2012—just as the ARC‑era of mobile puzzle games (e.g., Bejeweled, Candy Crush) was beginning to explode. The PSP’s Klonoa’s Dream and the Facebook Candy Collector had already proven that compelling, repeatable match‑3 loops can drive user engagement for months.

Technologically, Mystika was built on a modest 2D engine. Side‑view, fixed flip‑screen visuals—common for the genre—allowed quick level design cycles. Players could either accept a timer or deactivate it, offering an optional “casual” mode that reduced frustration for those who preferred a more relaxed pace. The decision to include “hidden object” side stories was a nod to the Disney Explorer and Hidden Package lines, carried over from earlier UnikGame titles. In summary, Mystika neatly meshed the studio’s formulaic approach with a rising demand for hybrid puzzle experiences.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot: Lumina, a fantasy kingdom saturated with light, is under threat from Tenebria, queen of the Dark World. Player characters—players’ avatars—are tasked with venturing through eerie caves, mystic castles, and crypt‑filled ruins to retrieve or destroy golden tiles that hold the kingdom’s stability. Along the way, they rescue Luminos allies, banish beasts, and wield spells learned throughout the journey. While the storyline headlines adventure, its execution is shallow: “Tenebria, the queen of the dark world,” and “players will learn spells to clear gold tiles” barely scratch the surface.

Characters & Dialogue: The narrative voice is an omniscient narrator that offers stage directions and occasional flavor text. Dialogue rarely breaks the monotonic rhythm of match‑3 level calls, and deeper character interactions (e.g., with Luminos or Tenebria) are essentially cutscenes that add visual variety but not narrative depth. The voice-over description epically outlines each level’s objective while reusing generic phrases such as “wield your spell,” which could have been leveraged more creatively.

Underlying Themes: The most explicit theme lies in the classic “light versus darkness” duality. Gold tiles represent the kingdom’s vitality, while “steel plates” and “enchained” obstacles symbolize oppressive darkness. The spells—such as “remove gold tiles” or “gain more time”—serve as symbolic tools that enable players to restore balance, reflecting the narrative of curation and healing. The hidden‑object segments occasionally expose motifs of searching for lost things, reinforcing the notion that recovery of hidden treasures (literal and metaphorical) is key to restoring harmony.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop

The main mechanic remains the granulated match‑three puzzle loop. Players use a mouse to swap two adjacent tiles, aiming to line up three or more identical items to clear gold tiles. The consistent visuals—gem‑like icons—and simple swapping gesture cost little learning overhead. However, what distinguishes Mystika is its “super‑set” of obstacles (steel plates, chained tiles, creatures) and the dual modes (optional timer). This is an attempt to differentiate from the vast sea of match‑3 titles.

Obstacles & Enemy Interaction

- Steel Plates: Locked overlay that must be removed by matching over the underlying tile. Once removed, the gold tile is accessible—this adds a “layered” challenge.

- Chained Tiles: Unmovable blocks that function as a hurdle; the player must match other tiles to “chain” them, creating an opening. While this adds puzzle depth, it sometimes creates frustrating “dead‑ends” where possible matches are blocked by unreachable chains.

- Creatures: Bats, turtles, spiders appear. Players must click repeatedly to defeat them. This mechanic introduces a slight action element into the puzzle, but the character interaction is limited to point‑clicking, which can feel repetitive because of the low skill ceiling. The bats’ ability to restore gold tiles and turtles’ plate‑placing can turn a promising path into a tedious “luck‑or‑strategy” scenario.

Spell System

Enabling players to cast spells like “remove gold tile” or “gain additional seconds” adds an extra strategic layer: deciding when to spend the one or two spells is critical. However, spells are introduced slowly and rarely become critical for completing a level, which makes them feel more like optional trick than a core strategy asset.

Hidden Object Levels

Interspersed in the match‑3 progression are hidden‑object puzzles. Players search for listed items within a cluttered environment. This design choice gives variation, but the similarity to Disney Explorer or Jigsaw Puzzle games and the simple point‑select interface put it squarely in the niche of low‑engagement casual pastimes.

Level Design & Progression

The game comprises six worlds, each with a handful of levels. There is a linear progression—levels unlock sequentially. The plateau in design variety can result in the same tile set or obstacle combination repeating across several worlds. That said, the inclusion of a minimal “Boss” level facing Tenebria in the final world briefly amplifies stakes.

User Interface & Controls

The button‑less, mouse‑click drag UI is clear and responsive. Snap animation on tile swap is tasteful but sometimes too fast, making it hard to gauge if a match is in effect. The timer bar displays seconds left; turning it off with a button is straightforward but the time limit itself can become a source of stress for casual players.

World‑Building, Art & Sound

Visuals: The 2D hand‑drawn art style adopts a medieval fantasy aesthetic. Characters and backgrounds carry a nice mix of round, cartoonish personalities and gothic edges—e.g., bat symbols, dungeon ladders, and luminous crystals. However, the level backgrounds use a fixed screen viewport (flip‑screen), meaning each scene stays static once the player navigates. That limits environmental immersion but suits the game’s casual nature.

Colour Palette: While gems are brightly colored, the gold tiles themselves are golden gold, creating a clear target. Contrasting colors—such as the black silhouettes of enemies—make the required matches obvious. The “dark world” iconography—full of black shapes—helps reinforce the narrative theme when displayed during boss levels.

Sound Design: The soundtrack is a blend of light canon and slow‑tomato theme. Background ambient music shifts with each world: a gentle piano for caves, a minor key for castles, and a more ominous chord for the dark world. Sound effects for tile swaps and spell casts are sharp and short; the click sounds when fighting creatures are intentionally repeated to provide a subtle action rhythm. Though not groundbreaking, the audio is sufficient, never intrusive, and aligned with the slower pacing required by the puzzle loops.

Reception & Legacy

At release, Mystika achieved a modest reception. On the user rating front, Big Fish Games’ formatted

review pages rebalance to a handful of 5‑star “good experience” comments, while some

users on forums complained about monotony in later levels. The game was available

for free to test, consistent with the shareware model that many casual titles

employed.

Commercially, it sold via Big Fish; Amazon sales data report roughly $6.89 price points, with a low rating of ~2.9/5 from a handful of reviews. On GameFAQs, only one user (the one that owns it) provides statistical ownership.

Legacy: Mystika is effectively an entry‑level franchised title. Its influence is minimal on the broader puzzle scene; the game did not introduce a groundbreaking mechanic or create a distinct sub‑genre. Yet, it demonstrates how a dev studio can reliably produce cross‑platform casual titles that tap into universal tropes: survival stories, light vs. darkness, the pleasure of quick puzzles. The player base remained stable through the franchise, with Mystika 2, Awakening of the Dragons, and Dark Omens capitalizing on the mechanics used here.

Conclusion

Mystika: Between Light and Shadow is a well‑executed, if unsubtle* example of casual match‑three design. Its strengths lie in a tidy interface, clear visual cues, and a balanced mix of matching, hidden‑object diversion, and light‑theme narrative. Its weaknesses are unmistakable: a shallow story, repetitive level design, and an under‑utilized spell system that doesn’t truly impact strategy.

For the casual player, especially within the Big Fish ecosystem, Mystika satisfies a craving for quick, low‑stress puzzle sessions. For scholars of game design, it remains a testament to the era’s churn‑able casual market—offering insight into how modest studios produced ready‑made experiences that fit the “download and play” fashion of the early 2010s. In terms of lasting impact, the game sits firmly in the mid-level tier of casual puzzle titles: not a watershed moment, but solidly functional. Thus, it earns a respectable yet restrained place in video game history—an exemplar of its genre and its era but not a transformative landmark.