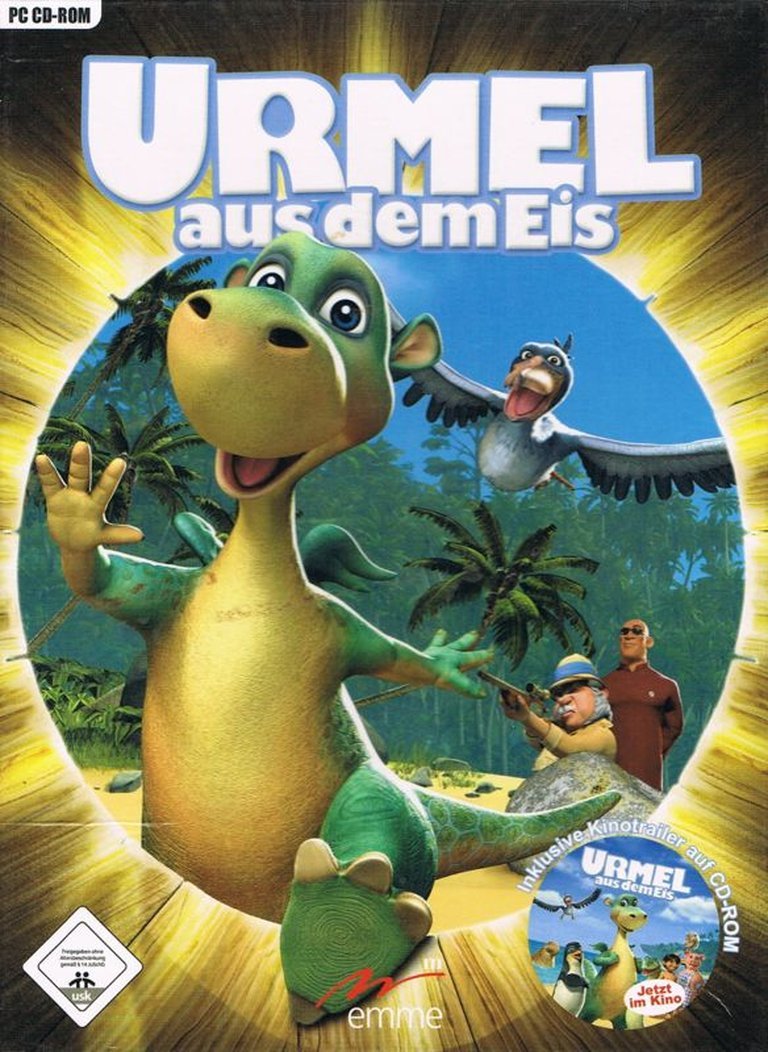

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: EMME Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: sensator AG

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: Jungle

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Urmel aus dem Eis is a 2006 Windows action-platformer game developed by sensator AG and published by EMME Deutschland GmbH, directly adapting the German animated film Urmel aus dem Eis (released internationally as Impy’s Island). Players control Urmel, a prehistoric creature hatched from an ancient egg frozen since the Ice Age, as they navigate eight vibrant levels across diverse environments including jungles, islands, and underground caves to evade the relentless pursuit of King Pumponell (a.k.a. ‘King Futsch’), a deposed monarch hunting him for Museum Director Zwengelmann. The game captures the whimsical charm of Max Kruse’s children’s franchise through arcade-style running and jumping mechanics, set against the backdrop of Professor Tibatong’s island of Titiwu populated by talking animals like penguin Ping and pig Wutz.

Gameplay Videos

Patches & Updates

Mods

Reviews & Reception

imdb.com (80/100): Wonderful adaptation of a wonderful book.

Urmel aus dem Eis: A Forgotten Gem of German Children’s Gaming

Introduction

In the pantheon of German cultural exports, few franchises have maintained enduring appeal quite like Max Kruse’s “Urmel aus dem Eis.” Originally a children’s book published in 1969, this beloved property has seen multiple adaptations including the famous 1969 Augsburger Puppenkiste puppet show, a 1995 animated series, and the 2006 computer-animated film “Impy’s Island.” However, the 2006 video game adaptation released by EMME Deutschland GmbH on Windows remains one of the most obscure yet fascinating iterations of this cherished IP. As a meticulously crafted jump ‘n’ run experience that faithfully transports the film’s vibrant world into interactive form, “Urmel aus dem Eis” represents an important, if overlooked, piece of European gaming history—a charming example of how regional cultural properties can successfully transition into meaningful interactive experiences for children. This review argues that despite its niche status and limited documentation, the game stands as a significant artifact that not only preserves German storytelling tradition but also demonstrates the potential of localized children’s gaming in an increasingly globalized industry.

Development History & Context

German Gaming in the Early 2000s

To properly contextualize “Urmel aus dem Eis,” we must first examine the German gaming landscape circa 2006. While Germany has consistently been Europe’s largest video game market in terms of revenue, its domestic development scene has historically been overshadowed by American and Japanese powerhouses. The early-mid 2000s saw German developers primarily focusing on family-friendly and educational titles, often tied to existing media properties—a strategic move to compete against the blockbuster franchises dominating global markets.

sensator AG, the studio behind “Urmel aus dem Eis,” was emblematic of this trend. Specializing in children’s entertainment software, sensator operated within a specific ecosystem where licensing established children’s properties was seen as the most viable business model. Unlike major studios with massive R&D budgets, sensator worked within tight constraints, producing games that could be developed quickly and sold at lower price points, often through retail channels already familiar with the source material.

Sensator AG and the Urmel Opportunity

sensator AG had previously worked on educational software and simpler game adaptations, making them well-positioned when EMME Deutschland GmbH—the German publisher holding the rights to the “Impy’s Island” film adaptation—sought to capitalize on the theatrical release with a companion video game. The timing of the game’s August 4, 2006 release (just months after the film’s February 17, 2006 debut in Germany) followed standard media tie-in strategy, leveraging the promotional wave of the film’s theatrical and eventual DVD release.

Technologically, the game was designed for the mainstream Windows PC market of its time, requiring only modest specifications (Intel Pentium III processor, 512MB RAM, Windows 2000, DirectX 9.0), ensuring accessibility to the broadest possible audience of German families. The developers wisely avoided attempting photorealistic 3D graphics that would have strained typical home computers, instead opting for a 2.5D approach that balanced visual fidelity with performance—a pragmatic decision reflecting the technological constraints of German households at the time.

Gaming Landscape Context

The mid-2000s represented a transitional period for children’s gaming. Nintendo’s DS (released 2004) and Wii (2006) were beginning to reshape how children interacted with games through touchscreens and motion controls, while mobile gaming was in its infancy. For PC gaming specifically, the market was saturated with licensed children’s titles, but few originated from European intellectual property—most were adaptations of American cartoons or global franchises. “Urmel aus dem Eis” stood out as a rare example of a game built around deeply German cultural heritage, tapping into nostalgia for older generations while introducing the property to new players.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Story Adaptation from Source Material

“Urmel aus dem Eis” faithfully adapts the narrative framework established in Max Kruse’s 1969 children’s book “Urmel aus dem Eis” and its 2006 animated film adaptation. The game’s plot follows the original story where an Urmel—an extinct creature suspected to be the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and mammals—hatches from an egg preserved in an iceberg that washes ashore on the magical island of Titiwu (an acronym formed from “Ti”batong, “Ti”ntenklecks, and “Wu”tz). The island is inhabited by Professor Habakuk Tibatong, his assistant Tim Inkblot, and various anthropomorphic animals who’ve learned to speak, each with distinctive speech patterns: Ping the penguin replaces “sh” sounds with “pf,” Wawa the monitor lizard lisps, Schusch the shoebill pronounces “i” as “ä,” and Seel-Fant the elephant seal diphthongizes vowels in his Wagnerian-inspired songs.

The game specifically focuses on what is arguably the central conflict of the narrative—the pursuit of Urmel by the deposed King Pumponell (also known as “King Futsch”), who seeks to add the rare creature to his trophy collection. The king, having been forced to abdicate when his homeland Pumpolonien became a republic, arrives on Titiwu with his servant Samuel (Sami) determined to capture Urmel for Museum Director Zwengelmann. This cat-and-mouse dynamic forms the core gameplay loop, with players controlling Urmel as he navigates increasingly complex environments to evade capture.

Character Representation

What makes “Urmel aus dem Eis” particularly noteworthy from a narrative perspective is how it preserves the distinctive characterization from the source material. The game doesn’t merely use the characters as visual assets but incorporates their speech idiosyncrasies into the experience. While the limited technology of 2006 prevented full voice acting implementation across gameplay (though the cutscenes likely featured voice clips from the film’s cast including Wigald Boning as Professor Tibatong and Anke Engelke as Wutz), the written dialogue and text elements maintain each character’s unique speech patterns.

Urmel himself is portrayed consistent with his literary depiction—a playful, somewhat irresponsible creature whose dialogue reflects “children’s language” patterns. His design captures the youthful, dinosaur-like appearance described in Kruse’s work, with the distinctive “Mupfel” cry that became a household word in German-speaking regions through the book series.

Thematic Elements

Beyond its surface-level chase mechanics, the game subtly engages with the same thematic depth found in Kruse’s original work. The central conflict embodies a tripartite philosophical struggle: Professor Tibatong represents the scientific perspective (wanting to study and understand Urmel), Zwengelmann embodies the destructive scientific impulse (wanting to dissect and preserve Urmel as a specimen), while King Pumponell personifies pure trophy hunting (seeking Urmel for personal glory).

This thematic framework, while presented in a child-friendly manner, carries genuine conceptual weight about our relationship with nature and scientific discovery. The game, like its source material, subtly advocates for conservation through Urmel’s journey—emphasizing that some wonders are meant to exist freely rather than as museum exhibits or hunting trophies. The denouement, where Tibatong tricks King Futsch with a bucket supposedly containing “invisible fish,” reinforces the narrative’s gentle satire of vanity and hubris.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop

“Urmel aus dem Eis” functions as a classic behind-view (third-person perspective) jump ‘n’ run platformer where the primary objective across all eight levels is evasion. Players control Urmel as he navigates intricate platforming sequences while being pursued by King Pumponell and his henchmen. The game’s fundamental mechanics center around precise jumping, timing-based obstacle navigation, and environmental puzzle-solving—not unlike contemporaneous platformers like “New Super Mario Bros.” but with a distinct German flavor.

Each level presents unique challenges tied to its environment, with progression gated by the player’s ability to successfully evade capture while reaching designated exit points. The “run from king Pumponell” mechanic creates genuine tension uncommon in children’s games of this era, as capture typically results in immediate game over—reinforcing the high stakes of Urmel’s situation.

Level Design and Progression

The game features eight levels spread across varied environments including jungles, icy caverns, coastal regions, and the underground lake cave system described in Kruse’s novel. Each area cleverly integrates elements from the original story: the jungle level incorporates Wawa’s giant clam shell residence, the cave level features the nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”) vents central to the story’s climax, and coastal areas showcase Seel-Fant’s rocky perch.

Level progression follows a thoughtful difficulty curve. Early levels introduce basic platforming mechanics with generous safety margins, while later stages demand precise timing and execution, incorporating story-specific elements like the “slumber barrel” submarine sequences adapted from Wutz’s conversion of her barrel home into a rescue vessel during the cave-in sequence.

Innovation lies in how the game translates narrative elements into playable mechanics. For instance, the cave level featuring nitrous oxide vents requires players to manage Urmel’s altered movement physics when exposed to the gas—a clever gameplay interpretation of the story moment where King Futsch mistakes a crab for Urmel while under the gas’s influence.

Interface and Controls

Operating under the “direct control” interface paradigm typical of mid-2000s platformers, “Urmel aus dem Eis” delivers responsive, intuitive controls optimized for younger players. The movement schema utilizes standard WASD or arrow key configurations with dedicated buttons for jumping, interaction, and special abilities unlocked through story progression.

The UI is deliberately minimalist—a strategic choice considering the target demographic. Key elements include:

– A subtle stamina meter visible only during intensive chase sequences

– Environmental indicators highlighting interactive elements

– A clean checkpoint system that saves progress without interrupting flow

– Character-specific icons representing which allies might assist Urmel in each level

One notable design choice is the absence of traditional health bars or lives—failure results in immediate restart of the current section, maintaining narrative continuity by framing each attempt as another evasion sequence rather than treating failure as “death.” This approach aligns with the game’s overall ethos of preserving the source material’s gentle tone while still providing meaningful challenge.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction and Environments

“Urmel aus dem Eis” achieves remarkable fidelity to Reinhard Klooss and Holger Tappe’s 2006 animated film, translating its distinctive visual style into interactive form. The game employs a bright, saturated color palette that captures the idyllic tropical island setting of Titiwu (referred to as “Tikiwoo” in the English film adaptation) while maintaining the slightly stylized character designs from the film.

Each of the eight levels demonstrates impressive environmental diversity for a children’s game of this era. The jungle areas feature dense foliage with animated wildlife elements; the coastal regions showcase dynamic water effects and Seel-Fant’s prominent rock formation; and the cave systems implement sophisticated lighting to create an appropriately mysterious atmosphere during Urmel’s refuge from King Pumponell.

The visual design excels particularly in character animation. Urmel’s movements capture the playful, almost carefree nature described in Kruse’s text, while environmental storytelling elements—like Ping attempting to invade Wawa’s clam shell home—provide delightful Easter eggs for fans of the source material. The game’s ability to maintain visual consistency while offering interactive environments represents significant technical achievement for a small German studio working within budget constraints.

Sound Design and Music

The audio component of “Urmel aus dem Eis” leverages James Dooley’s musical score from the film adaptation (Dooley also composed for “Spider-Man: Shattered Dimensions” and “The Simpsons Game”), creating immediate familiarity for players who had seen the movie. The soundtrack dynamically shifts based on gameplay context—tranquil melodies during exploration sequences, tense percussion during chase sequences with King Pumponell, and triumphant themes upon successful level completion.

One of the game’s most impressive audio achievements is its implementation of character-specific speech patterns without relying on full voice acting throughout gameplay. Instead, the developers employed selective voice clips for key moments, supplemented by text dialogue that visually represents each character’s speech impediment (e.g., Schusch’s dialogue displayed with “i” consistently replaced by “ä”). This economical approach maintained the distinctive personalities while working within technological limitations.

Environmental sound design receives thoughtful attention, with region-specific audio cues enhancing immersion: jungle levels feature authentic bird calls and rustling foliage, coastal areas incorporate crashing waves and Seel-Fant’s characteristic singing, and cave levels employ echoing footsteps and subtle gas emissions. The game’s sound design exemplifies how deliberate audio implementation can elevate even modestly budgeted titles.

Atmosphere and Tone

What distinguishes “Urmel aus dem Eis” is its consistent maintenance of the source material’s warm, gently humorous tone. Unlike many children’s games that resort to frantic pacing or excessive rewards systems, this title respects Kruse’s original vision—a world where anthropomorphic animals live harmoniously despite their quirks, where conflict arises from personality differences rather than violence, and where solutions emerge through cleverness rather than force.

This atmosphere manifests in gameplay through subtle choices: King Pumponell is portrayed as comically inept rather than genuinely threatening; environmental hazards rarely result in punitive consequences; and interactions with supporting characters consistently reinforce the story’s themes of friendship and understanding. The game’s pacing deliberately avoids the hyperactive tempo of many children’s titles, instead allowing moments for players to absorb environmental details and character interactions—a decision reflecting the contemplative aspects of Kruse’s original narrative.

Reception & Legacy

Contemporary Reception

Documenting “Urmel aus dem Eis’s” initial reception proves challenging due to its status as a regionally focused children’s title. The game received minimal coverage in major gaming publications, unsurprising for a German-exclusive release tied to a localized intellectual property. Its MobyGames entry (added May 22, 2018, despite the game’s 2006 release) shows only one player has collected it, and the platform lacks any critic or player reviews—a testament to its obscurity in the global gaming community.

Within Germany, the game likely found moderate success among fans of the film and established Urmel enthusiasts. Children’s gaming titles of this nature typically sold through non-traditional gaming channels—bookstores, toy stores, and educational retailers—making traditional sales tracking difficult. Its USK 0 (no age restriction) rating and CD-ROM distribution model targeted parents seeking educational yet entertaining content for young children, a market segment often overlooked by mainstream gaming press.

Reviews for the film “Impy’s Island” suggest the game arrived during a period of renewed interest in the Urmel franchise. As TeeJayKay noted in a 2007 IMDb review: “This is, after all, the third adaptation of the original book (not counting the 2-D cartoon series) and, I must say (being very skeptical about remakes), a very good one.” The game likely benefited from this positive reception to the film, though direct evidence remains scarce.

Historical Significance

Historically, “Urmel aus dem Eis” represents an important, if under-documented, example of European attempts to build viable gaming ecosystems around regional cultural properties. While Japan successfully exported franchises like Pokémon and Animal Crossing internationally, and America dominated with properties like SpongeBob and Disney adaptations, Europe struggled to create globally competitive children’s gaming IPs.

This game demonstrates how German developers attempted to carve out space in the market by deeply leveraging domestic cultural touchstones rather than chasing international appeal. By building a game around a property already beloved across generations in Germany (Urmel has served as the official mascot of Germany’s national ice-hockey team since 2010), sensator AG pursued a “local-first” strategy that prioritized domestic resonance over global marketability—a business model that has seen renewed interest in recent years with the success of regional indie titles.

Legacy and Influence

Despite its obscurity, “Urmel aus dem Eis” contributes to an important legacy within German gaming: the tradition of adapting culturally significant children’s literature to interactive media. Its approach influenced subsequent German-developed children’s titles like “Tabaluga: Die Rettung aus dem Eispalast” (2000), which similarly leveraged established domestic IP for gaming purposes.

More significantly, the title represents an early example of what we might now call “transmedia storytelling” in children’s entertainment—an integrated approach where films, books, and games coexist as complementary narrative experiences rather than isolated products. While not as sophisticated as modern transmedia franchises, “Urmel aus dem Eis” helped establish patterns that would later flourish in properties like “Lauras Stern” and “Pettersson und Findus.”

Perhaps most enduring is how the game preserved and transmitted German cultural heritage to new generations. For children discovering Urmel through this game in 2006, it served as an on-ramp to the broader literary tradition, potentially inspiring them to explore Kruse’s original novels. In this sense, the game functioned as both entertainment and cultural preservation—a role increasingly recognized as valuable in today’s globalized media environment.

Conclusion

“Urmel aus dem Eis” may not rank among the technical marvels or commercial titans of gaming history, but its significance extends far beyond sales figures or graphical fidelity. As a faithful adaptation of Max Kruse’s beloved children’s literature that successfully translated narrative depth into interactive form, the game represents an important milestone in European gaming—the attempt to build compelling interactive experiences around culturally specific stories rather than chasing homogenized global appeal.

The game’s enduring value lies in how it balances entertainment with cultural preservation, using platforming mechanics not merely as challenges but as narrative devices that reinforce Kruse’s original themes. Its thoughtful integration of linguistic quirks, environmental storytelling, and narrative-consistent gameplay systems demonstrates remarkable respect for source material—a quality all too often sacrificed in licensed games.

Historically, “Urmel aus dem Eis” belongs to that category of regional children’s titles that rarely receive critical attention but play crucial roles in developing local gaming ecosystems. It stands as evidence that meaningful gaming experiences can emerge from culturally specific contexts, offering perspectives often absent from the Anglo-American dominated gaming landscape.

In the final analysis, “Urmel aus dem Eis” earns its place in video game history not through revolutionary mechanics or technical achievements, but through its quiet success as cultural stewardship—a game that helped keep a cherished German story alive for new generations while demonstrating that localized narratives deserve space in the gaming world. For historians examining the diversification of global gaming culture, this unassuming platformer serves as a valuable case study in how regional identities can thrive within interactive entertainment. It is, ultimately, a small but significant victory for cultural preservation through play—a testament to the idea that sometimes the most meaningful games aren’t the ones that conquer global markets, but those that successfully root themselves firmly in the soil from which they grew.