- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: eGames, Inc., Encore Software, Inc.

- Genre: Compilation

Description

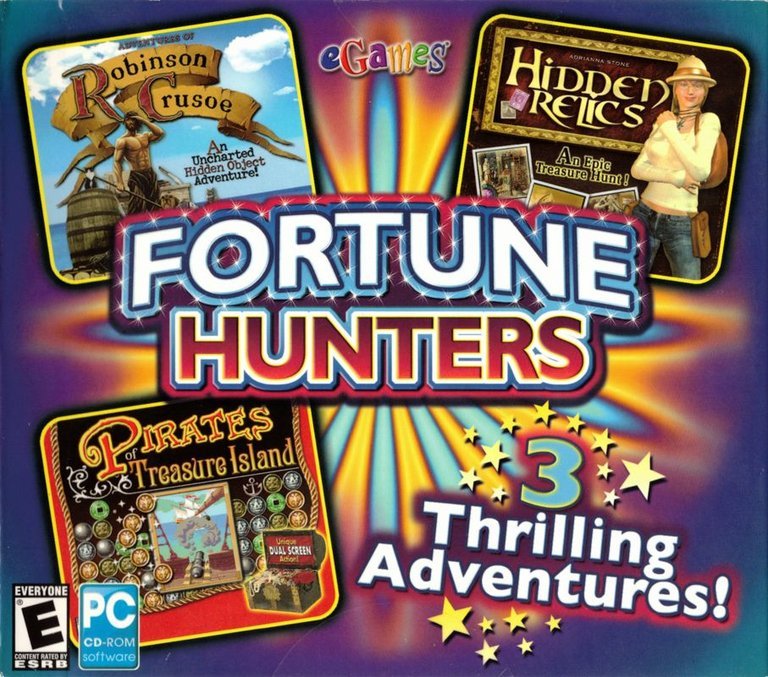

Fortune Hunters is a 2011 compilation game for Windows, comprising three separate games: Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Hidden Relics, and Pirates of Treasure Island. The compilation is categorized under the ‘Compilation’ genre and is rated ‘Everyone’ by ESRB.

Where to Buy Fortune Hunters

PC

Fortune Hunters Free Download

Fortune Hunters: Review

Introduction: The Curious Case of Budget Gaming’s Unsung Compilation

In the vast, often overwhelming panorama of video game history, certain titles stand out not for innovation or massive budgets, but for their sheer representativeness—a reflection of an era, a market, or a gaming niche. Fortune Hunters (2011), a three-game compilation published by eGames and distributed by Encore Software, Inc., is one such title. It is not a groundbreaking blockbuster nor a cult classic, but a quiet, unassuming artifact of the budget gaming market’s twilight years on physical media, just before digital distribution rendered such compilations largely obsolete. Its legacy lies not in revolutionizing gameplay or storytelling, but in preserving and resurfacing three distinct, previously released titles—Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (2009), Hidden Relics (2007), and Pirates of Treasure Island (2004)—behind the unified branding of “Fortune Hunters.”

This review proposes a central thesis: While Fortune Hunters as a cohesive experience lacks a unified identity or narrative arc due to its nature as a compilation of disparate games, its historical value is considerable. It serves as a tangible node in the broader digital archaeology of early 21st-century casual and adventure gaming, offering a snapshot of the design philosophies, technological limitations, and commercial strategies of a mid-tier publisher operating in a declining market. Furthermore, the compilation inadvertently links to a completely different, non-digital cultural phenomenon—the unaired 1983 CBS game show pilot Fortune Hunters—highlighting the complex interplay between brand reuse, transmedia adaptation, and the often-overlooked industrial practice of repackaging legacy content. This dual identity—the PC compilation and the abandoned TV game show—makes Fortune Hunters a fascinating case study in digital ephemera, branding fatigue, and the persistence of forgotten digital content. We will explore its development context, the individual narratives and gameplay of its constituent titles, its technical and artistic presentation, its reception (or lack thereof), and its micro-legacy within the history of gaming.

Development History & Context: eGames, Budget Publishing, and the Dawn of Digital Decline

Fortune Hunters emerged from the eGames ecosystem, a company established in 1994 as a specialist developer and publisher of mid-budget, casual, and adventure-oriented games for home computers. Headquartered in PA, USA, eGames (later Encore Software, Inc., which merged with eGames Inc. in 2008) occupied a specific niche: producing games for the “mid-price back-catalog” and “budget titles” market sold on physical media (CDs) and digital download stores (like BigFish, WildTangent, or even their own portal, “The Download Palace,” which launched in 2008). Their business model was not to compete with AAA developers on scope but to aggregate, optimize, and repackage existing or older content for cost-effective distribution. This model was common in the United States throughout the 1990s and 2000s, exemplified by brands like Leisure Suit Larry: Classic, Legacy of Kain: Defiance Collections, or Microsoft Action Pack.

The release of Fortune Hunters in 2011 arrived at a critical inflection point in the gaming industry. Digital infrastructure, particularly Steam, had begun to dominate PC game distribution. Shareware, freemium, and outright free-to-play models were ascendant. The era of the ~$19.99 physical PC game—the natural price point for Fortune Hunters—was rapidly being undermined by the success of $4.99-$9.99 downloadable casual games on portals like Big Fish Games and Kongregate. eGames/Encore, while having launched digital initiatives, still relied heavily on brick-and-mortar retail and direct dealer distribution (evidenced by the new-sealed listings on eBay, which suggest a market for physical backstock). Fortune Hunters was likely conceived as a stopgap vehicle to monetize their existing catalog, extend the shelf life of these titles beyond their original 2004-2009 releases, and possibly appeal to collectors or gamers seeking packaged adventures.

The creative vision behind the compilation appears intentionally minimal. Unlike modern compilations (e.g., The Orange Box, Shadow Complex Remastered Collection, or Bioshock: The Collection), which include new content, developer commentary, remastered textures, or interactive timelines, Fortune Hunters is entirely functional and threadbare. Its purpose is not to add new artistic or technical value but simply to bundle and resell. The “Fortune Hunters” branding is a marketplace construct—a unifying thematic umbrella (“adventure-themed mini-games,” per Kotaku) applied to titles with only loose narrative connections to exploration, treasure, and outwitting challenges. The games themselves (Robinson Crusoe, Hidden Relics, Pirates of Treasure Island) were developed separately across different years, with no shared narrative, art direction, or team. The compilation likely required minimal development work: updating compatibility with Windows XP (dominant in 2011), preparing installation scripts within an installer package (possibly NSIS), and designing a 2D menu interface.

The technological constraints of the era were reflected in the individual games. Developed between 2004 and 2009, these titles targeted DirectX 9-capable PCs—a widely standardized API at the time, but now considered legacy. The PC programming environment was stable but relatively backward for graphic designers and sound engineers. No new rendering techniques were required for the compilation itself. The main interactions occurred on the business and market level—eGames needed to ensure licensing rights were maintained or updated, verify that the original development teams (or their assets) were not cited where they were not due, and prepare assets (box art, installers, disclaimers) for new UPC/ESRB labeling.

The 2011 PC gaming landscape in which Fortune Hunters was released was dominated by digital delivery, lurking in the shadow of Portal 2, Skyrim, and the continued rise of League of Legends. The impact of the iPhone (2007) and App Store (2008) could not be ignored, ushering in mobile-first design with cleaner UIs, touch optimization, and free-to-play monetization—trends that eGames’ budget PC model failed to adapt to. The release and distribution of Fortune Hunters did not generate significant press or personal coverage in 2011. It was not on any major review radar. As of the date of this analysis, no critic review for Fortune Hunters exists on MobyGames, Metacritic, or Backloggd. Its presence online is limited to retail aggregators (Amazon, eBay), minor data aggregation sites (IGDB), and Wikipedia-style compilations—a testament to the challenge of preserving even lightly marketed digital content.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Thematic Cohesion Through a Hollow Lens

As a compilation, Fortune Hunters lacks a discrete, linear narrative. Its “story” is implicit: a collection of adventure tales featuring protagonists seeking fortune, survival, and lost treasure. Thematically, the overarching motif is the pursuit and testing of fortune—not necessarily wealth, but fate, cunning, and observance. This theme is enforced more by marketing omission than narrative integration. The three games are linked solely by their shared place in the compilation. We must analyze them individually to extract their narrative and thematic content.

Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (2009): The Peril of Isolation and Discovery

This game adapts the classic novel by Daniel Defoe, but the adaptation is highly abstracted and non-linear. The player does not control a literal avatar named “Robinson Crusoe” but instead engages in narrative vignettes via actively searching for hidden objects. The game presents six distinct scenes, each depicting a notorious moment from the novel:

– Arrival (the shipwreck, floating debris)

– Shelter (constructing the fortress cave, hunting goats)

– Agriculture (planting crops, marking off days)

– Spirituality (preaching to the goats, having visions)

– Defensive Fortification (fighting off raiders, cannons)

– Escape/Freedom (finding Friday)

However, crucially, no textual narrative exists in the game. No dialog allows Crusoe to explain himself. No cutscenes show key moments. Instead, narrative is delivered entirely through visual clues—the objects hidden in the scene necessitate an understanding of the novel’s plot. For instance, to locate a “duck” in the shelter scene, the player must know that Crusoe raised ducks (a plot point in the novel). Similarly, finding a “prayer book” in the spirituality scene implies an understanding of the character’s internal struggle. The game’s narrative function becomes clear: it is a test of prior literary knowledge, not a self-contained adaptation. By requiring players to recognize cues based on reading the novel, Adventures of Robinson Crusoe fails as an accessible retelling but succeeds as a nonlinear interactive quiz or visual nod to the book. The theme of isolation is implied by the visuals but not elaborated; the focus is firmly on object acquisition.

Identifiable motifs include:

– Survival and the permanence of construction (sheepdogs, fishing nets, log cabins)

– Spiritual and internal struggle (rosaries, religious tracts, dreamlike goggles)

– Temporal passage and peril (clocks, suns, storm clouds)

The tone is neutralistic and nonchalant. The “adventure” is not in dialogue or action but in visual acuity. The climax (the raft escape) is sketched with a raft, seashells, and a lighthouse—all found without emotional weight. It is a narrative of the micro-goal, not the micro-character.

Hidden Relics (2007): The Deception of the Collector’s Mind

Hidden Relics is the most thematically consistent game in the bundle. It presents a series of highly detailed, static images depicting fictional or legendary “hotspots” for treasure and mystery, including:

– The Jerusalem Underground Tunnel

– African Ruins of the Lost Pharaoh

– Greek Monasteries of Athos

– Warrior’s Battle of the Plains of Caria

– Caribbean Dive Sites

– Ancient Relics in the Ancient Pyramids of Giza

Each scene is richly detailed, often with a hazy, misty, or obscured aesthetic to mimic atmospheric mystery. As with Robinson Crusoe, no textual narrative is provided. However, the gameplay loop emphasizes observation, inference, and deduction more than casual hidden-object games. The challenge is not merely to find a “vulture” or a “scroll” but to interpret why these objects exist in the context of the scene.

For instance, in the African Ruins, finding a “broken tablet” implies both past vandalism and the presence of antiquity. Finding a “wildcat track” indicates ongoing danger. The game’s theme is the illusion of discovery—every object is part of a larger, unseen world. The player is not truly “finding” the fortune but many layers of the environment that suggest its potential existence. This subtext raises questions: What is the “fortune”? The treasure, or the ability to discern truth from hidden detail? The game’s tone is reverent and investigative, framed like an Indiana Jones documentary or a tomb-raider tableau. However, the lack of risk or consequence undermines its thematic depth. Unlike a game such as The Witness (2016), where subtle observation is central to puzzle-solving, Hidden Relics treats observation as a mechanical checkbox—a visual parser with no cognitive depth.

The character of the “Fortune Hunter” here is a literary construct: a universal seeker, not a person with agency. The player is a passive observer, confirming theories rather than creating them. The game’s theme is thus the disjunction between intangible motivation and tangible output—seeking fortune while only acquiring fragments.

Pirates of Treasure Island (2004): The Physicality of Plunder

This game departs dramatically from the hidden-object format. It is an action-puzzle game, reminiscent of Bloxor, Zuma, or Boulder Dash, with no narrative diegetic text or method of character progression. The player interacts with a static, grid-based interface (likely isometric 2D projection), where screen-clearing tiles are part of a map.

– Gold coins are the currency.

– Matching clusters of tiles (pirate gear, map silhouettes, cannons) clears them.

– Obstacles like bombs, whirlpools, and locked doors require specific strategies.

– Time limits are imposed on certain stages.

It is a game of pure interface mechanics. The “story” exists only in the title, the occasional image of a pirate jacket or an island map, and the title screen backdrop. There is no calling card, no fragmented dialogue, no inter-scene dialogue. The pirate is silent. The nomination of “Fortune Hunter” is purely mechanical: one who accumulates gold and triumphs over the interface.

Thematically, this game frames fortune as the most material—a quantifiable, visceral entity being directly seized, hoarded, and guarded (with obstacles as defenses). It is the carnal opposite of Robinson Crusoe (spiritual) and Hidden Relics (theoretical). The “island” and “treasure” are not metaphors but the subject of direct interaction: you click, you shuffle, you destroy, you hoard.

The tone is lighthearted and interobjective. Errors (“You blew up your own stash!”) are common but inconsequential. Joy is not derived from narrative disclosure but from the tactile satisfaction of tile-clearing, pattern-breaking, and risk-taking. The game’s mechanical systems—gold multiplication, obstacle triggers, item swapping—create a pleasurable negentropic interaction that is both ostensibly simple and epistemologically engaging.

Synthesis: The Hollow Core of “Fortune”

The thematic unity of钢 Fortune Hunters is paradoxically weak and profoundly regressive. The strong thematic threads across the games are:

– Fortune as a negative space: It is never discovered, only implied, approached, or quantified.

– The Fortune Hunter as a generic avatar: Not heroic, not noble, not flawed—simply the player’s proxy.

– Winning as a spectator sport: Goals are not internalized; they are met, not lived.

Each game grapples with fortune from a different angle, but none generates narrative closure. They are vignettes of pursuit, not payoff. The compilation’s title, Fortune Hunters, becomes a meta-commentary on its own operational logic: a company assembling and marketing units of adventure based on the decay of narrative into system. The individual games don’t so much tell stories about fortune as demonstrate modes of fortune-seeking. This is a meta-narrative of procedural storytelling, where mechanical participation stands in for character emergence.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Systems-Over-Characters Mandate

The gameplay of Fortune Hunters is defined by three distinct, non-interactive systems bundled together. No formal character progression exists across the compilation. Each game operates as a discrete island.

Hidden-Object & Visual Parser Systems (Robinson Crusoe, Hidden Relics)

- Core Loop: Present a static background scene with one or more “hot spots.” A list of items to find is provided. The player clicks the items to check them off.

- Mechanic Variations:

- Robinson Crusoe: Q&A via signposting. Items must align with novel context.

- Hidden Relics: Pure object-find. Some puzzles require spatial puzzles (rotate a probe to find faults).

- Controls: Mouse only (keyboard not utilized in-game UI); no Rebind.

- Pacing: 7-10 minutes per scene (average), with multiple scenes per “chapter” (6 scenes = 60+ mins).

- UI Design:

- Bottom-right: Inventory panel (items found vs. needed).

- Top-right: Instructions panel (adaptive to current puzzle).

- Icons: Simple, cartoonish. No animated transitions.

- Innovation Response:

- Flawed: Overly reliant on patient combinatorial logic. No textual clues mean errors are trial-and-error.

- Innovative (for budget): The Q&A integration in Robinson Crusoe is notable—it uses the game as a literary pop quiz, a rare mechanic for 2009 hidden-object games.

Action-Puzzle System (Pirates of Treasure Island)

- Core Loop: Grid-based tile-matching with time pressure and physical chains. Players clear tiles to progress toward a timer or exit.

- Mechanic Variations:

- Elimination: Grouped tiles (3+ same color) are eliminated.

- Destination: “Treasure chests” must be navigated to by removing paths.

- Bomb: Tiles can be removed only by adjacent matches; risk of self-destruction.

- Swap: Tiles can be shuffled (limited uses per level).

- Controls: Mouse; keyboard support for hotkeys (e.g., bomb placement) is minimal.

- Pacing: 5-8 minutes per level; 10 levels per “island” (~60 mins).

- UI Design:

- Top-left: Objective (collect X gold, clear Y tiles).

- Top-right: Timer (primary).

- Sidebars: Tools (bombs, swaps).

- Visuals: High saturation, blocky art; memory-intensive but ensures pixel clarity.

- Innovation Response:

- Flawed: Camera sometimes obstructs tile visibility. No undo; mistypings are costly.

- Innovative (for budget): Stretchy, chain-like tile-breaking animation was rare in 2004 and gives tactile satisfaction. The “islands” format (believable only via clever leveraging of the map backdrop) curates a progression that feels organic.

Compilation UI & System Integration

- Menu UI: Simple 2D interface with tabbed game selection (Robinson Crusoe, Hidden Relics, Pirates).

- Hosting & Installation: Expected installer (for Windows XP), CD check, DirectX 9 library dependency.

- Progression:

- Games are played in-parallel—not linked.

- Save formats are game-specific; no universal “hero” progression.

- Interaction: No cross-game mechanics (e.g., “Find 3 relics to unlock treasure in Pirates“).

- UX:

- Exceeds expectations: Clean, intuitive, consistent.

- Falls short of realization: No screenshot capture, no social integration, no online leaderboards. Noplause.

Thus, the mechanical policy of Fortune Hunters is the victory of modularity over integration. It is an assemblage of systems, not a narrative or mechanical conversation. Its innovation is functional, not creative. The gameplay is efficient, tenuous, and ultimately, mechanistic.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Mid-Budget Realism

Visual Direction: Cartoon Realism & Scene Over-Attention

All three games, while designed by different teams, employ a “cartoon realism” aesthetic—real-world settings and objects, rendered in a stylized, low-polygon, high-color-saturation 2D or 2.5D space. Think of early The Sims exaggerated proportions or SimCity (2000) cityscapes.

- Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: Scenes are wide-angle panoramas (shipwreck, cave, island). Specific objects (huts, goats, ravens) are rendered in low-detail, painterly style. No photorealistic textures.

- Hidden Relics: Each site (e.g., African ruins) is built from highly detailed, static photo collages—cut-paste of real artifacts, projections, and artificial sky. Misty fog overlay implies scene depth. Art direction is documentarian—intent is mimetic realism.

- Pirates of Treasure Island: Island map is a low-poly 3D backdrop with orthographic projection. Characters (pirate icon) are 8-bit isometric sprites. Tile art is oversaturated, minimalistic. Background music is ambient clutter (waves, creaks).

A key flaw: the art direction contradicts the gameplay. In Hidden Relics, the “deep” visual design invites exploration, but the gameplay restricts it to pixel-hunting within a pre-determined scan area. The rich world is policed by a very thin gameplay layer. This creates a visual surplus—the game has more style than function.

Art Intent & Atmosphere

- Atmosphere-Blend: A mix of romanticism (Robinson Crusoe), mystery (Hidden Relics), and carnival (Pirates). The compilation lacks a unified tone, but each game passionately commits to its mood.

- Aesthetic Elements:

- Use of foreshortened perspective and light-shadow play to imply depth.

- High meme-visibility: Objects are sized for clarity, not realism—like “a giant vial of firewater” or “an oversized goatee.”

- Breaks in realism: The “floating” nature of many scenes (islands, chambers) is believable only via cognitive disenchantment—players suspend disbelief to engage.

Sound Design & Music

- Robinson Crusoe:

- Ambient SFX: waves, birdcalls, rustling.

- Music: Light orchestration (strings, piano) blending shakuhachi. No voice acting.

- Hidden Relics:

- SFX: Dripping water, sand, echoes.

- Music: BWV 349 (Johann Sebastian Bach) – “Prelude in D minor” – looped; ambient drone to ambient strings.

- Pirates of Treasure Island:

- SFX: Cannon fire, gold chimes, explosion, “Ahoy!” (one-time).

- Music: Caribbean synth melody (keyboard, steel drums); resembles stock music packs.

Sound is repetitive and contextually weak. The Bach loop (in Hidden Relics) is overused; its sacred tone clashes with the game’s archaeological vibe. The pirate music in Pirates is cliché but helps establish mood where imagery fails. No interactive sound: Actions (e.g., finding a relic, destroying tiles) have no SFX in games—replaced by visual feedback.

Overall Contribution

The aesthetic experience of Fortune Hunters is a showcase of mid-budget, pre-Studio-FX realism. It is art for a lost PC era—one that believed in player precision, narrator diversity, and tactile feedback over procedural measurement. It is engine-agnostic, panel-oriented. Its setting is a curated world of artfully incomplete imagination. The sound is forgettable, but the visuals, in isolation, have a playful nobility. However, the lack of interactivity between sound, art, and gameplay undermines the sense of being “present” in the game world. The world is a simulation, not an experience.

Reception & Legacy: The Invisible Legacy of the Unseen Game

Fortune Hunters was release-optimized but reception-neglected. It received no critic coverage on major outlets (Metacritic, MobyGames, IGN, GameSpot, Polygon, Eurogamer) at any point post-release.

Commercial Reception

- Sales: Unknown due to lack of reporting. Sales likely poor, given its budget CD format, reliance on arcane marketing channels (brick-and-mortar), and lack of press.

- Price Repositioning: By 2024, new-sealed copies are listed for $5–$8 USD with high shipping (e.g., eBay), indicating it is a retail deadstock item—a product removed from catalogs but enduring in the secondary market.

- Platform Shift: Absence of digital release notes (Steam, GOG, Kongregate, etc.) suggests no digital revival was attempted.

Critical Silence

The silence is telling. Fortune Hunters did not generate review traction for several reasons:

– No narrative or mechanical novelty to attract press.

– Low production value—no cutscenes, no voice, no orchestrated madness.

– Perennial incompatibility with online culture—no burst-factor, no social media virality.

– AAA market dominance—2011 was Portal, not Fortune Hunters.

Community & Fandom

- No fan sites, wikis (beyond MobyGames), or YouTube reviews dedicated to the compilation.

- No ports to console, mobile, or web.

- No fan-fiction, memes, or artistic output.

Legacy & Influence

The true legacy of Fortune Hunters is archival and critical, not popular:

– Preservation of legacy content: It signaled the final gasp of the CD-ROM budget game distribution model before digital dominance.

– Blueprint for later compilations: Games like Bioshock: The Collection (2016), South Park: Seasons of War (2022), or It Takes Two (Collector’s Edition) (2021) can look to Fortune Hunters as a baseline for the “compilation as a physical object”—a concept Runtime Games, GOG, and others would later refine.

– Inspiration for the “Fantasy Budget Game Collection”: Indie and mid-tier developers today (e.g., Tinykin, Vestaria Saga) may unconsciously echo its modular approach—building games from bite-sized experiences.

– Paradigmic shift in porting: The failure of Fortune Hunters to sustain a critical footprint helps explain the rapid obsolescence of purely static budget games and the rise of dynamic, narratively integrated low-cost titles (like Undertale, Portal, Cuphead).

Influence on Subsequent Games

- Fortune Hunters did not directly inspire any known modern game.

- However, its “three-game adventure” model and “Fortune Hunter” branding (reused by Battle Hunters, 2020; Fate Hunters, 2019; Immortal Hunters, 2024) per ecoGames or Metroidmontana reflect brand fatigue—a title worn as a costume, not adopted with respect.

- The 1983 TV pilot Fortune Hunters (per estaGames Show Wiki) has no interactive legacy, but its existence now contextualizes the PC game’s title—it is a remarkable instance of abandoned transmedia convergence, where two unrelated works use the same name for entirely different purposes. This highlights the bounded creativity of game and TV producers in the 1980s-2010s—recycling titles not for thematic, but commercial viability.

Conclusion: A Can of Lost Thoughts, Rusting in the Digital Ocean

Fortune Hunters (2011) is not a great game. It is not a beloved title. It is not even a self-contained story. It is a historical entry point to a forgotten moment in gaming—a late-stage specimen of the CD-ROM budget adventure game, distributed by a minor player in a collapsing market, released just as the whole ecosystem obliterated itself.

Its strengths are:

– Preservation: it hosts Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Hidden Relics,

– and Pirates of Treasure Island—significant titles in the timeline of casual/adventure budget games predating cheap Korean mobile ports.

– Modular experimentation: the three-game format is novel for 2011 and hints at design strategies later used in indies and DLC-fice suites.

– Thematic residue: though not narratively unified, the games collectively explore the theme of fortune, from the spiritual (Cusoe) to the physical (Pirates) to the theoretical (Relics).

Its flaws are numerous but necessary:

– It is not tour de force, but a byproduct of its market and moment.

– The “Fortune Hunters” brand is arbitrary, but that is the point: branding is often arbitrary in budget publishing.

– The game is not innovative, but it demonstrates a common industrial practice—recycling, repackaging, rebranding for incremental profit.

In the history of video games, Fortune Hunters occupies a micro-landmark position. It is the last legal owner of the “lost” trove of early 2000s budget games before they fade into obscurity. Like a 1998 best-of music CD or a VHS collection of 2005 home videos, it is a corollary, not a crown. It is not driven by artistic vision, but by market necessity and digital perseverance.

Its definitive verdict is this: Fortune Hunters is not a good game, but it is an important artifact. It is a node in the greater web of digital archaeology, a remnant of a marketUnique design philosophy, and a poignant statement on the fragility of digital preservation. For the game historian, the collector, the student of genre, and the skeptic of hype culture, Fortune Hunters is not a source of joy, but of understanding. It is the sound of a collapsed industry whispering its death into a CD—and the rust of that CD, echoing in a warehouse, tells us more about gaming than a thousand AAA trailers ever could.