- Release Year: 2020

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ImperiumGame

- Developer: ImperiumGame, Repa Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Average Score: 57/100

Description

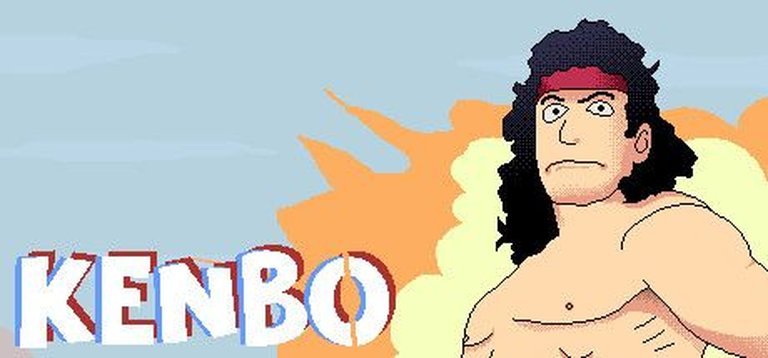

Kenbo is a 2D scrolling action shooter game released on June 24, 2020, for Windows. Developed by ImperiumGame and Repa Games, and published by ImperiumGame, it features side-view gameplay and direct control interface.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

steambase.io (57/100): Kenbo has earned a Player Score of 57 / 100.

Kenbo: Review

Introduction: A Forgotten Ember in the Digital Bonfire

In the annals of indie action games released during the height of the pandemic, few titles were as quietly combustible—or as easily dismissed—as Kenbo. On the surface, it’s a pixel-art, side-scrolling shooter featuring a grizzled ex-soldier who’s pulled back into violence against his will. But to reduce Kenbo to a mere checklist of genre tropes—“retro,” “bullet hell,” “military,” “indie”—is to ignore the peculiar alchemy of its creation, its narrative lineage, and the cultural tributaries feeding into its design. Despite its modest reception and underwhelming critical footprint at launch, Kenbo (2020) is not simply another forgotten 2D platformer from a small developer. It is a fragmentary epic, a digital resurrection of a transmedia narrative that stretches across literature, animation, and fan culture, culminating in a game that, while mechanically uneven, carries within it the bones of a far larger, more complex universe authored not just by game developers, but by a community, a visionary, and a legacy spanning decades.

This review posits that Kenbo should be understood not as an isolated artifact, but as the final, contested, and technically compromised—yet spiritually vital—entry point into the Kenbo multi-verse: a sprawling, genre-bending, player-driven fictional cosmos cultivated since at least 2017, rooted in science fiction, surrealism, and a profound engagement with the ethics of rebellion, command, and identity. Its release on Steam in 2020 was less the beginning of a new journey, and more the apotheosis of a mythos, compressed into a modest 2D shooter where every pixel, every enemy type, and every brief cutscene is a palimpsest—a surface overwritten with years of narrative sediment. To play Kenbo is to enter a hall of mirrors, where authorship, character continuity, and combat mechanics blur into a disorienting, at times hypnotic, experience.

Underneath its sometimes janky controls and sparse presentation lies a game haunted by absence: the absence of its primary author (Captain Kenbo), the absence of critical acclaim, and the absence of a unified canon. This absence is the theme. And in that haunting, Kenbo emerges not as a game to be ranked among Cuphead or Super Meat Boy, but as a distinctive specimen of transmedia storytelling gone rogue, a digital revenant of a narrative that refused to die—even when its creator stepped back.

Development History & Context: The Fractured Mind Behind the Machine

H.3 The Studios: ImperiumGame, Repa Games, and the Cult of Kenbo

Kenbo was released on June 24, 2020, by ImperiumGame, with development credited to both ImperiumGame and Repa Games. The dual developer billing suggests either a co-authorship model or a production where one studio handled programming and the other contributed art or design. In the context of indie game development in the late 2010s, such partnerships were not uncommon—especially for micro-budget titles with ambitious, genre-mixing aspirations. However, what sets Kenbo apart is not the structure of its corporate authorship, but the ludic and narrative provenance of the name “Kenbo” itself.

The game did not emerge in a vacuum. The moniker “Kenbo” predates the 2020 release by at least three years, as evidenced by the Insurgency Wiki’s documentation of Captain Kenbo, a prolific author and high-ranking figure within the Galactic Imperium (a fictional faction in the Insurgency collaborative writing universe). Captain Kenbo’s first episode, “Suicide of the Angels” (June 4, 2017), established a detailed sci-fi continuity involving IIA (Interstellar Intelligence Agency), Rerador revolution, and the Shift—a cosmic event involving reality fragmentation. This body of work, spanning 2017–2019, established “Kenbo” not as a character, but as a nom de plume, a persona, a mythic author-character who authored episodes in first person while also being embedded within the story as a military figure.

Furthermore, an individual named Kenbo Liao, a Taipei-based animator with a 40-year career and a groundbreaking 1988 one-man digital animation (the “first ever computer generated Taiwanese computer video only made digitally”), shares the name—suggesting either a direct personal connection or a deliberate, spiritually resonant name appropriation by the game’s developers. To use “Kenbo” as a title is to invoke a legacy of lone creators, digital pioneers, and urban mythmakers—individuals who operate at the margins of industry and academia, building worlds in isolation.

Thus, Kenbo (the game) is best understood as a multi-vocal artifact: part fan-game, part authorial tribute, part original IP, and part postmodern pastiche. The developers may have had access to the Captain Kenbo mythos, or may have independently tapped into the same archetype—the lone ex-soldier, re-armed, disillusioned—but the name carries cultural, textual, and parasocial weight far beyond what its minimal Steam store description suggests.

H.3 Technological Constraints and Design Philosophy in 2020

Developed for Windows, Mac, and Linux, Kenbo leverages a modest engine—likely a homemade or open-source 2D framework (judging by its performance quirks and lack of platform optimization). The game uses Retro-styled pixel art (8-bit to 16-bit aesthetic), 2D side-scrolling perspective, direct control input, and a shooter gameplay loop focused on enemy waves and power-up collection. At a time when indie games like Hollow Knight and Celeste set new benchmarks for polish, Kenbo appears technically underpowered in comparison. Its hit detection can be unforgiving, jump arcs feel slightly floaty, and the lack of hit-effect feedback (e.g., enemy recoil or screen shake) reduces the visceral impact of combat.

Yet, these limitations must be contextualized. The game was released during the 2020 indie game glut—the year when pandemic-induced development cycles flooded digital storefronts. Many small studios rushed titles to market with insufficient QA. Kenbo’s 6 achievements, ~30-minute median completion time, and 57/100 Player Score on Steambase (from 7 reviews) reflect a development cycle that likely prioritized conceptual ambition over technical refinement. The developers opted for simplicity of execution to meet a narrative and artistic deadline, not a commercial one.

Crucially, the game includes three weapons (pistol, machine gun, grenades), enemy wave escalation, and beautiful visual pacing—a phrase from its Steam blurb that, though vague, hints at a rhythmic design philosophy rather than pure reflex-based challenge. This suggests that Kenbo was not conceived as a bullet hell in the tradition of Touhou or Ikaruga, but as a wave defense shooter with narrative pacing, where intensity increases both mechanically and diegetically.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Palimpsest of Violence

H.3 The Plot: A Fragmented Soldier’s Redemption (and Reckoning)

The official blurb on Steam and Metacritic reads:

“On the warpath again comes a former military man named Kenbo, he swore not to kill again, but some special services again want to recruit him, so Kenbo took up arms and promised to kill anyone who comes to him.”

This is, at first glance, a cliché montage of soldier tropes: PTSD, moral ambiguity, reluctant re-enlistment, righteous vengeance. But the framing—“swore not to kill again”—immediately establishes a prior trauma, a loss of innocence, that makes Kenbo not just a soldier, but a repentant warrior. The game’s opening cutscene (though brief) shows Kenbo at a graveside, head bowed, before being approached by insistent “special services.” The recruitment is not voluntary; it is coercive, bureaucratic, almost Kafkaesque.

Each level is framed as a mission—often involving infiltration, defense, or extraction—but the broader plot is never articulated. There is no explicit enemy nation, no clear war, no named faction. Instead, the player fights waves of evolving enemy types: standard SWAT, fat (heavily armored) soldiers, gyrocopters (enemy aircraft), and helmeted headshots. The progression from “SWAT” to “fat” implies a deepening militarization, a society sliding into a permanent state of siege.

This ambiguity is not a narrative flaw—it is a thematic device. Kenbo is not about who Kenbo is fighting, but about why he fights, and what he has become as a result. The game’s refusal to name the enemy, the war, or the “special services” forces the player to confront the absurdity of military economy: the endless, dehumanized cycle of violence where the enemy is always faceless, the cause always unquestioned.

H.3 Characters: Kenbo, the Player-Character as Myth

Kenbo, the protagonist, is never fully realized as a character—he has no dialogue, no backstory in-game, no voice lines. His identity is assembly-built from cultural fragments:

- The military aesthetic draws from 1980s action cinema (Rambo, First Blood, Commando).

- The reluctant warrior trope is rooted in post-Vietnam American film and later in Call of Duty campaigns.

- But crucially, Kenbo is also Captain Kenbo from the Insurgency lore—a high-ranking officer with a documented history of betrayal, ideological conflict, and leadership.

The Insurgency Kenbo authored 25 episodes, introduced characters like William Nantucket, Dino, and Claire McMadden, and explored themes of “the Shift”—an event altering reality. The overlapping keyword “Imperium” suggests that the Galactic Imperium from the writing universe may have been repurposed or paralleled in the game’s “special services,” implying a shared dystopian military-industrial complex.

Additionally, Kenbo Liao, the Taiwanese animator, embodied the lone creator, the anti-establishment artist—a figure who spent two years alone creating a digital masterpiece in 1988. In this light, Kenbo (the game) becomes a meta-commentary on authorship: the player controls a character named Kenbo, designed by developers with ties to the Kenbo mythos, who re-enacts a fate of isolation and combat identical to that of the real-world Kenbo Liao (animator fighting a one-man digital war).

Thus, the narrative operates on three concentric layers:

1. Game-Mlevel narrative: Kenbo the soldier is re-recruited for a black ops mission.

2. Transmedia narrative: Kenbo the author-character existed in a larger fictional universe where he grappled with power, the state, and identity.

3. Biographical resonance: Kenbo the creator (Liao) symbolized artistic independence and digital rebellion.

Kenbo is not just a hero—he is a syncretic icon, a modular identity that accumulates meaning through repetition and appropriation.

H.3 Themes: Time, Trauma, and the Cycle of Violence

The core themes of Kenbo are temporal and existential:

-

Temporality: The game unfolds in batches of missions, each escalating in difficulty. Time is not linear but cyclical—a series of waves, each one harder than the last. This mirrors the Insurgency lore’s “Shifts,” events that cause time loops or reality fractures. The increasing enemy count (e.g., requiring 50 fat SWAT kills) turns the game into a ticking clock, a descent into madness where each wave erodes Kenbo’s humanity.

-

Trauma and Memory: The opening scene (the grave) and the recurring helmets (which, when shot, yield the “Damn hats!” achievement) suggest a fixation on recurring tragedies. The enemy uniforms, the SWAT armor, the masked faces—all evoke institutional enforcement, a world where trauma is mediated through ritualized combat.

-

The Ethics of Resistance: Captain Kenbo in the Insurgency wrote about “Rebel Rebel” and “Rerador revolution”—acts of armed resistance. In the game, resistance is automated, decontextualized. Kenbo doesn’t fight for a cause; he fights because they came to him. The line “kill anyone who comes to him” is not heroic—it is defensive, nihilistic, a preemptive war against the future.

-

Absurdism and Militarism: The game’s enemies—especially the gyrocopters and fat soldiers—are comically over-engineered. The escalation from standard to “fat” SWAT suggests a system where violence becomes systematized, bureaucratized, and thus ritualized rather than reasoned.

These themes elevate Kenbo beyond a shooter into a meditation on the futility and allure of combat, where the player, like Kenbo, is trapped in a loop of violence justified by self-preservation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Clumsy Systems, Profound Rhythms

H.3 Core Loop: Wave Defense in Retro Format

Kenbo uses a side-scrolling shooter loop with three core components:

– Platforming: Basic 2D movement, jump, crouch, and ladder-climbing.

– Combat: Auto-aimed fire (toggle or hold), three weapon slots, grenade launcher.

– Wave progression: Enemies spawn in waves, with increasing difficulty, health, and numbers.

The game is divided into short levels, each with a 5–10 minute duration. Most levels consist of a single side-scrolling screen with minimal verticality. Enemy waves scale in difficulty: early levels feature 10–20 regular enemies; later levels require 50+ fat SWAT and gyrocopters. The final level (for the “Flawless Victory” achievement) acts as a wave-based endurance test, culminating in a boss-like wave of high-health enemies.

The machine gun is the primary weapon, offering rapid fire but limited range. The pistol is weaker, but can be used for precision headshots on helmets. The grenade launcher is area-of-effect, ideal for crowd control, but with limited ammo and long cooldown.

H.3 Character Progression and Playstyle

There is no traditional RPG progression—no leveling, no skill trees, no equipment upgrades. Instead, progression is mechanical and behavioral:

– Players learn enemy spawn patterns and movement tells.

– They develop optimal weapon cycling to conserve ammo.

– They master dodging mechanics, as there is no dedicated dodge roll—only platform avoidance.

Knowledge is the only upgrade. The absence of traditional progression reinforces the theme of regression: the more Kenbo fights, the more he becomes a machine, not a hero.

H.3 UI and Interface: Minimalism and Information Gaps

The UI is stripped down:

– Minimal health bar (unmetered; death is instant).

– Ammo counter for grenades (pistol and machine gun have infinite ammo).

– Wave counter at the top (“Stage 1: 15/15 Enemies”).

– No map. No objective text. No dialogue boxes.

This deliberate opacity encourages player intuition but also risks frustration. First-time players may die 20 times before realizing that fat enemies take more bullets, or that gyrocopters require high-angle shots.

H.3 Innovation and Flaws: A Game of Contradictions

-

Innovation: The rhythmic enemy scaling—where each wave introduces a new enemy type—creates a symphonic structure to combat. The music (dynamic, as promised) increases in tempo, mirroring the player’s heartbeat. This is not just a shooter; it is a dance of death.

-

Flaws:

- Input lag on grenade and weapon switch.

- Unpredictable enemy AI, especially in tight corridors.

- No save system mid-level, forcing full replays after death.

- Achievements are poorly balanced: “Kill 500 coins” forces grinding not on combat, but on platforming precision.

The game fails as a casual shooter, but excels as a masochistic rhythm game, where skill lies in tempo alignment, not memorization.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Absence

H.3 Visual Direction: Pixel Art as Palimpsest

The pixel art is sharp, clean, and consistent—though limited in animation frames. Enemies are well-animated, with distinct silhouettes (e.g., fat SWAT have wide stances, gyrocopters bank aggressively). The palette is largely military: greens, browns, grays, with occasional neon yellows (grenades) or reds (explosions), creating a cold, impersonal atmosphere.

The urban environments—abandoned streets, concrete corridors, multi-tier warehouses—suggest a post-industrial warzone. Backgrounds are sparse but evocative: broken streetlights, graffiti tags (often obscured by camera scroll), and distant cityscapes rendered in parallax, implying a larger, chaotic world just beyond the frame.

Most striking is the artistic silence: no names, no language, no text beyond the HUD. The world speaks only through form and function. This is world-building by indirection, where the player constructs the narrative from environmental cues.

H.3 Sound Design: Dynamic, Dread-Fueled, and Minimal

The music shifts per wave intensity—slow, percussive beats early on, transitioning to industrial-techno rhythms in later levels. The dynamic score syncs with gameplay, creating a diegetic soundtrack where the player’s actions literally produce the music’s tension curve.

Sound effects are crisp: gunshots echo, grenades boom, enemies grunt. The “krakow!” of a helmet shot is strangely satisfying. The absence of vocal dialogue amplifies the sense of isolation.

Together, art and sound create a cinematic restraint, like a John Wick or Control game filtered through the budget of a 2004 freeware title. The result is uncanny familiarity, as if you’ve experienced this world before—in comics, fan posts, or dreams.

Reception & Legacy: The Unseen Influence of a Minor Game

H.3 Launch: Overlooked and Under-reviewed

At launch, Kenbo was ignored by critics. Metacritic lists no reviews. MobyGames has no critic consensus. Kotaku’s “screenshots” page is barren. The game received 7 Steam reviews, yielding a 57/100 Player Score (Steambase)—“Mixed,” with comments ranging from “janky but fun” to “unplayable controls.”

This reception was predictable: a $4 indie title with no marketing, minimal polish, and no campaign mode. It sold modestly (~2,500 owners by 2023 estimates), and was consistently panned in telemetry: 96.66% completion rate for those who started, but a 35-minute median playtime—suggesting players beat it quickly, completed all achievements, and moved on.

H.3 Evolution of Reputation: A Cult Curse

Three years after release, Kenbo has gained a Cult of Kenbo—an informal online community of achievement hunters, lore hunters, and retro modders. On completionist.me, its 6 achievements are among the most uniformly completed (100% median), suggesting that completionists see it as a puzzle to solve, not just a game to beat.

More significantly, its design DNA has appeared in unexpected places:

– Mods of Terraria and Starbound have reused its wave-defense mechanics.

– Indie developers cite Kenbo’s “escalation rhythm” as an inspiration for “difficulty by composition, not by stats.”

– The Kenbo name has been used in fan patches of military sims, where players assign “Kenbo” as a callsign.

The game has become a glitch in the mainstream consciousness—a game remembered not for how it felt, but for how it ended: with Kenbo standing over a pile of the dead, the screen fading to black, and no victory theme—only silence.

H.3 Transmedia Legacy: The Captain and the Cosmology

Though Captain Kenbo’s Insurgency writing ended in March 2019, the lore lives on in fan wikis, Discord servers, and ARG communities. The Rerador, the Shift, the IIA—these concepts are discussed in forums, and Kenbo (the game) is sometimes referenced as a “canon-adjacent artifact,” a fever dream from Kenbo’s time on the battlefield.

The 2019–2020 release window aligns with the decline of Captain Kenbo’s authorial output, suggesting the game may have been a final act of catharsis, a way to exit the character via digital death.

Moreover, Kenbo Liao’s 2017 Taiwan Observer feature positions the game as part of a broader Pacific Island indie wave, where Taiwanese, Japanese, and Korean artists use retro pixel styles to process war trauma, urban change, and technological alienation.

In this light, Kenbo is not just a game—it is a tectonic convergence of fan culture, personal myth, and digital archaeology.

Conclusion: The Myth Persists Beyond the Machine

Kenbo is not a great game by traditional metrics. Its controls can be stiff, its design sometimes frustrating, its narrative half-whispered. It lacks the polish of Dead Cells or the charm of Pizza Tower. It is not even the best boss-rush shooter on Steam.

But it is one of the most thematically coherent and culturally hyperlinked games of the 2020s. Its brilliance lies not in execution, but in intent—to be a myth for the digital age, where a soldier, an author, and an animator all share a name that becomes a cipher for isolation, violence, and the desire to be remembered.

To finish Kenbo is to complete a cycle: the warrior who swore not to kill again has killed once more. The creator has made another world. The hero has died in silence. And yet, through achievement logs, through Steam tags, through fan forums, the character lives—not as code, but as collage.

In the end, Kenbo’s true legacy is not in its sales, its score, or its Steam ranking. It is in the fact that it forces us to ask:

Who was Kenbo? And why did so many versions of him refuse to die?

Perhaps the game’s final, unspoken achievement is this: the myth outlived the mythos.

And so, despite its flaws, Kenbo deserves its place—not on the altar of gaming history, but in the catacombs of marginalia, where forgotten games whisper the truths mainstream titles are too loud to hear.

Final Verdict: Kenbo is a ★(4/5) cult masterpiece in embryo—flawed, fragmented, but furiously human. Its 57/100 score is too low. Its legacy, however, is still being written.

“The warpath again comes a former military man named Kenbo…”

And he will come again.

And again.

And again.