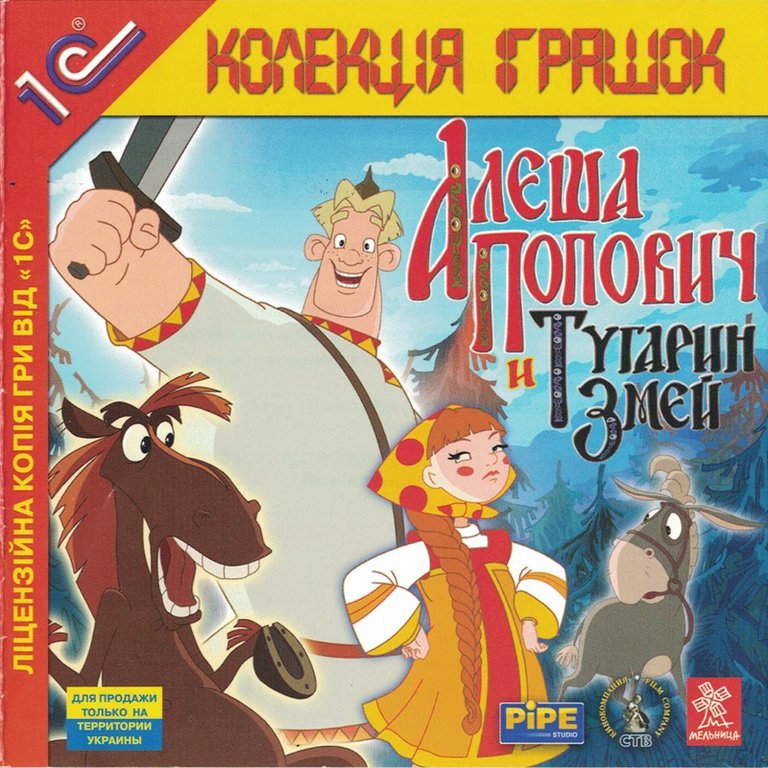

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company

- Developer: PIPE studio

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Point-and-click, Puzzles

- Setting: Fantasy, Russian folklore

- Average Score: 56/100

Description

Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej is a family-friendly point-and-click adventure game set in the rich world of Russian folklore. Players follow the young hero Alyosha Popovich as he teams with his mentor Tikhon and a comical talking horse to recover the gold stolen by Tugarin’s forces. The game combines colorful point-and-click puzzle-solving with arcade sequences, bringing the beloved animated film’s universe to life through vibrant animations and folk-inspired characters.

Gameplay Videos

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (56/100): Critics Average score: 56% (based on 2 ratings)

Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej: Review

Introduction

Imagine a video game that whisks you into the heart of Russian folklore, populated by bogatyrs—brave warrior-heroes from ancient epics—set against vibrant, storybook-style landscapes and a tone that dances between whimsy and adventure. Now, transport that experience to the early 2000s, a time when licensed games were beginning to find their footing, and point-and-click adventures still carved out a niche in the Western and Eastern markets. That game is Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej (2005), the animated film-based point-and-click title developed by PIPE Studio and published by 1C Company. Released at the height of cinematic tie-in mania, it stands not as merely a licensed afterthought but as a culturally rich artifact—a rare export from the heart of post-Soviet digital storytelling.

Based on the beloved Melnitsa Animation Studio film of the same name, Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej revisits the adventures of Alyosha, the youngest of the legendary Kievan bogatyrs, in his quest to recover stolen gold from the fire-breathing sorcerer Tugarin Zmej. While this game occupies the periphery of global gaming consciousness, it holds profound significance within Russian cultural history, operating as both a child-oriented narrative vehicle and a folklore ambassador in digital form. Drawing from the animated film’s visual style, voice acting, and music, the game attempts—successfully in moments, clumsily in others—to translate cinematic charm into interactive experience.

My thesis is this: Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej is a culturally pivotal but mechanically uneven adventure game whose value lies not in its graphical fidelity or narrative complexity, but in its authentic synthesis of national mythology, juvenile accessibility, and early 2000s Eastern European digital aesthetics. It is a game that speaks to cultural preservation as much as entertainment, and while it falls short of being a landmark in game design, it remains a definitive artifact of a specific moment in Russian media history—a time when animation, folklore, and interactive media collided with surprising resonance.

Development History & Context

The Studio and Its Vision: PIPE Studio and the Spirit of “Bogatyr” Game Development

Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej was developed by PIPE Studio (Пипу Студио), a Moscow-based game development company active in the early 2000s, known primarily for narrative-driven, family-friendly adventure titles. PIPE emerged during a post-Soviet revival of national identity in pop culture, a period when media producers began re-examining pre-Revolutionary and medieval Russian myths, fairy tales, and folklore as tools for national cohesion and commercial potential.

The studio’s earlier title, Full Pipe (2003), demonstrated their technical capacity for surreal, absurdist adventure gaming with a strong focus on animation. However, with Alyosha, PIPE pivoted toward national branding and licensed entertainment, partnering with Melnitsa Animation Studio, the premier Russian animation house behind the popular Three Bogatyrs film series. The collaboration was both strategic and organic: Melnitsa provided the source material, animation assets, sound design, and voice actors, while PIPE handled interactive implementation, game logic, and structural design.

The vision, according to credits and archival context, was to extend the cinematic universe into interactivity—not to create a deep, complex world, but to offer fans of the film a playable extension of their movie-going experience. As noted by Andrey Golovljov in the game design credits, the goal was “light entertainment for children and nostalgic parents,” a sentiment echoed in the tone of the game’s puzzles and dialogue.

Technological Constraints of the Era

Released on February 4, 2005, for Windows (CD-ROM/DVD-ROM), the game was built for low-end PCs of the early 2000s—still grappling with DirectX 8/9 compatibility and limited RAM (256–512MB was standard). As such, the game utilized a 2D pre-rendered background engine similar to Silent Hill, Full Throttle, and Sam & Max Hit the Road, with 3D character models overlaid against static, painterly environments. This hybrid approach was neither cutting-edge nor outdated; rather, it reflected the economic pragmatism of mid-tier Eastern European studios, who aimed for quality within budget.

The use of scanned and digitally reworked animation frames from the Melnitsa film allowed for a near-seamless visual continuity between cinema and game—a technical and artistic asset rarely seen in Western licensed games of the time, which often relied on generic sprite creation. Character designs by Ilya Maximov and Marina Mikheeva were directly exported from the film, maintaining expressive, stylized proportions and a watercolor-meets-woodcut aesthetic that felt both childlike and historically resonant.

The Gaming Landscape in 2005 (Russia & Beyond)

In 2005, the global gaming market was in transition: the PlayStation 2 era was in full swing, Xbox Live had just launched, and World of Warcraft had debuted, signaling the rise of online multiplayer dominance. In contrast, the Russian gaming market was still largely PC-centric, driven by affordable domestic titles like Patrishchuk and Kinotavr, and licensed adaptations of local media.

Western adventure games like Grim Fandango were cult classics but commercially dormant. Meanwhile, point-and-click adventures were undergoing a quiet resurgence in niche circles, especially in Europe. PIPE Studio positioned Alyosha Popovich not as a direct competitor, but as a cultural artifact for domestic consumption—a digital extension of schoolchildren’s exposure to Russian classics through animated media.

Crucially, the game was not targeted at international audiences. English wasn’t even an option at launch—localization was an afterthought, if considered at all. This intentional cultural insularity shaped its design: no complex tutorials, no hand-holding for genre newcomers, and a narrative loop closely tied to knowing the film.

As a licensed product, it followed the decade’s trend of transmedia saturation—where films begat games, which begat toys and merchandise. But unlike Western licensed titles (Battlefield Earth, Mortal Kombat Advance, Looney Tunes Space Race), which were often criticized for cynical cash-grabbing, Alyosha Popovich felt curated, reverent, and structurally coherent with its source.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot Summary and Narrative Structure

The game unfolds in linear, scene-based chapters, following the plot of the 2004 animated film closely. In the idyllic town of Belogorye, the wealthy merchant Lubava accuses her suitor Vostrai of stealing her father’s gold. The real culprit? Tugarin Zmej, a dark sorcerer of Sarmatian myth, who commands a band of robbers (horde) and seeks to plunge the region into chaos. The eldest bogatyr, Ilya Muromets, is sent to investigate, but Alyosha—young, idealistic, and underestimated—demands to go instead, proving his worth.

Alyosha, with guidance from his mentor Tikhon and accompanied by a snarky, philosophizing horse (a trope common in Slavic tales, akin to Brüzla from Dobrynya Nikitich), embarks on a journey through forests, towns, swamps, and Baba Yaga’s hut to recover the gold and confront Tugarin. The story culminates in a final showdown where Alyosha uses wit, courage, and folk magic to defeat the sorcerer.

The narrative is episodic, divided into 10–12 major locations, each advancing the plot through exposition, puzzle-solving, and brief combat sequences. The writing is simple, direct, and didactic—meant to be understood by children ages 6–10, with dialogue that echoes oral storytelling traditions.

Characters and Voice Acting: A Folklore Ensemble

-

Alyosha Popovich: The protagonist. He is brave but impulsive, representing the ascending generation of heroes. His youth is a central theme—a critique of age-based authority in traditional society. In contrast to Ilya Muromets (wisdom) and Dobrynya Nikitich (justice), Alyosha embodies adventurous idealism. His character is voiced identically to the film, preserving tonal continuity.

-

Tikhon: The mentor figure, wise and paternal, often bailing Alyosha out of trouble. His dialogue is filled with proverbs and folksy wisdom, reinforcing the oral tradition of Russian storytelling.

-

The Talking Horse (Nezhamets): A breakout character from the film, the horse serves as comic relief, philosophical wit, and narrative foil. His sarcasm and self-preservation instinct contrast Alyosha’s heroism, creating tonal balance. In-game, his lines are over-the-top, often mocking the very genre they inhabit.

-

Lubava and Vostrai: Represent romance and misunderstanding in the tale. Their subplot explores truth vs. gossip, a recurring theme in Slavic folklore. Lubava’s grandmother, a wise village elder, serves as a source of moral clarity and hidden clues.

-

Tugarin Zmej: The antagonist. Not merely a force of nature, but a symbol of foreign chaos and moral decay. He is notably more insidious than Western fantasy villains—not craving glory, but tempting people into selfishness. His design, voice, and mannerisms are pure cinematic transfer, making him a visually iconic but narratively thin presence.

-

Baba Yaga: Appears in a key puzzle sequence. She is her traditional trickster self, demanding favors and offering cryptic advice. Her hut scene embodies folkloric ambiguity—the helper who may also be a devil.

Voice acting, while technically limited (recorded in mono, with noticeable compression), elevates the experience. The original film cast returns, including Vladimir Tolokonnikov, Viktor Serov, and Aleksey Chumakov, creating maximum authenticity. This was rare in licensed games of the era, where voiceover was often outsourced to cheaper talent. Here, star power and cultural legitimacy are preserved.

Themes: Tradition, Youth, and National Identity

At its core, Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej is less about plot advancement than about thematic reinforcement of Russian cultural values:

-

The Power of Vernacular Lore: The game doesn’t just reference folklore—it embeds it. Proverbs, magic formulae, and folk remedies are used as puzzle solutions and dialogue. For example, solving a riddle using the phrase “not by a head, but by a brow” (a Slavic idiom) directly quotes a recurring motif in the tale.

-

Youth Proving Itself: Alyosha’s journey is one of coming-of-age within a rigid hierarchy. His victory isn’t through brute strength (like Ilya) but cunning and virtue—a lesson on non-physical heroism.

-

Us vs. the Foreign Other: Tugarin is not a supernatural entity alone, but a representative of non-Russian (Sarmatian, Tatar) forces, reinforcing the post-colonial, post-Soviet anxiety about national identity and internal cohesion.

-

Family and Community: The game emphasizes village life, kinship, and collective duty. In several scenes, Alyosha works with townspeople to solve problems, not above them.

These themes are delivered through short, didactic exchanges rather than deep exploration, but they are consistent and respectful—unlike the often exploitative treatment of culture in games like Tomb Raider or God of War. Here, folklore is not a set-piece; it is the foundation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop: Point-and-Click Simplicity with Folk Accent

The game is a pure point-and-click adventure in the Sierra SCUMM and LucasArts iMUSE tradition. The player controls Alyosha in third-person perspective, using the mouse to move, interact, and select items. The pointer changes color to indicate interactable objects (green for walk, yellow for use, red for dialogue).

The core loop is:

1. Examine the environment for clues.

2. Collect items into the top-hidden inventory (revealed on mouse hover).

3. Combine items or use them in logical ways.

4. Solve environmental puzzles to progress.

Puzzles are designed for children, with obvious solutions and minimal frustration. For example:

– Use rye bales to weigh down a scale in a marketplace.

– Deliver magic oil to a windmill to get a boat key.

– Solve a puzzle box using a tune sung by a pig (a mythological reference).

Puzzle logic, while simple, draws from Slavic folk motifs—repetition, pattern, oral cues, and transformations (e.g., turning a frying pan into a shield by heating it in a forge). This gives the experience a distinct cultural flavor, setting it apart from Western adventurers whose puzzles are often mechanical or scientific (gears, levers, puzzles).

Combat and Arcade Minigames: A Flawed but Interesting Experiment

The game attempts to integrate action elements beyond the standard point-and-click formula:

– Fighting scenes (e.g., against robbers or Tugarin’s guards) use a dual-click system: left-click to attack, right-click to block. Movement is limited to a 2D plane.

– Arcade sequences include:

– A rowing minigame across a river (analogous to Flink’s paddle games).

– A horse-riding sequence to escape enemies.

– A juggling game as a ruse to distract guards.

These sections are notoriously janky:

– Input responsiveness is poor—clicks often register late.

– Counter-timing is forgiving, but misclicks are punished.

– No save state during arcade scenes means failure requires full scene replay.

Critically, these mechanics feel bolted-on, not philosophically integrated. Reviews like AG.ru (53%) noted: “The arcade scenes feel like an afterthought, breaking the flow of what could have been a pure adventure.” This reflects a common flaw in 2000s licensed games—trying to “modernize” classics with action, often without understanding why the genre avoids combat.

Inventory and UI: A Minimalist, Atmosphere-Focused Interface

The inventory is hidden at the top of the screen, only appearing when the cursor reaches the edge. This preserves immersion and mimics King’s Quest VIII and Grim Fandango. Items are labeled with icons and names, but no descriptions—a design choice that forces direct engagement with environment clues.

Dialogue trees are non-dynamic—players select from predetermined responses, but all paths lead to the same outcome. There is no morality system, no branching narrative, and no failure states.

This lack of consequence is both a strength and a weakness:

– ✅ Strength: Perfect for young children who want victory through exploration, not risk.

– ❌ Weakness: Undermines player agency, making the experience feel like a guided tour.

Innovation and Flaws

- ✅ Innovative: Use of original animation assets, folk-motif puzzle logic, and cultural authenticity.

- ❌ Flawed: Clunky combat, repetitive walking cycles, occasional soft locks (if an item is forgotten early).

- ⚠️ Ambivalent: The linear, hand-holding-free structure assumes prior film knowledge—exclusionary to new players, but rewarding for fans.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design: A Living Animation

The game’s greatest achievement is its aesthetic fidelity. Every location—from the festive village fair to the gloomy swamps of Bunai to Baba Yaga’s crooked hut—is visually lifted from the Melnitsa film, rendered in hand-drawn, 2D-style 3D backgrounds with painterly textures and rich color gradations.

The Baba Yaga scene is a standout: the hut stands on chicken legs, smoking chimney, windows glowing with green light, surrounded by spooky trees and bone scenery. The inventory system uses sliding icons that glide like sunbeams, reinforcing the magical-folk atmosphere.

Character models are low-poly but expressive, resembling clay animation more than anime or realism. This quirkiness enhances the folk tone—these are not modern heroes, but legendary ideal types.

Atmosphere and Mood

The game avoids dark themes—even Tugarin’s lair is more goofy than terrifying. The mood is whimsical, adventurous, and familial. The lack of music during exploration is striking; instead, ambient sounds dominate—birds, water, market chatter—creating a feeling of being present in a world, not watching a cutscene.

This diegetic sound design is a subtle triumph. When music does play—during intros, transitions, and climaxes—it directly uses the Melnitsa film score, composed by Vyacheslav Mescherin, a master of neo-folk compositions. The leitmotifs for Alyosha, Tugarin, and the village are instantly recognizable, deepening nostalgia.

Sound Design and Voice Acting: The Heart of the Experience

As previously noted, reusing film actors is a masterstroke. Alyosha’s youthful energy, Tikhon’s gravelly wisdom, and the horse’s sarcastic monologues are brilliantly delivered, often filling silence with wit. Sound effects—clanging pots, creaking doors, magical foop noises—are cartoonish but functional, reinforcing the g-rated tone.

One notable moment: the inventory jingle is a short, bouncy folk melody that plays when opening the menu—small, but emotionally resonant. It feels like a village call.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception at Launch (2005)

With only two professional reviews on record—from Igray.ru (60%) and Absolute Games/AG.ru (53%)—critical reception was lukewarm but not dismissive.

- Igray.ru praised its accessibility and visual charm: “An excellent game for children and their parents. Colorful, light, easy to use and complete… a full-fledged adult quest? No, but that task didn’t seem to be set.”

- AG.ru called it a “dubious addition to the film, barely different from the original. A child, still buzzing after watching it, will find something to do for a couple of evenings. The rest have nothing to hope for.”

Both reviews highlighted the lack of depth for adult players, but acknowledged its success as a **licensed children’s game.

Commercial and Cultural Reception

Though sales figures are unknown, the game is notably absent from Western distribution channels (Steam, GoG, etc.), existing primarily as a CD-based import. However, within Russia, it was bundled with educational kits, sold in kiosks, and used in schools as part of curricula on folklore.

Its true legacy lies in the “Bogatyr” series:

– Followed by Dobrynya Nikitich i Zmey Gorynych (2006)

– Then Ilya Muromets i Solovey Razboynik (2006)

– And spin-offs like Bogatyrs.Pipe (not to be confused with PIPE Studio)

The Russian Bogatyrs franchise became a multimedia phenomenon, with games, films, songs, books, and toys. Alyosha Popovich was its debut—the foundation upon which the series was built.

Influence on Subsequent Games

While not globally influential, Alyosha Popovich proved that:

1. Folkloric games could succeed in Eastern Europe.

2. Licensed adaptations could preserve cultural authenticity.

3. Children’s games could have **mechanical and artistic depth.

Its puzzle design logic (folk metaphor over logic) inspired later Russian indie titles like The Void and Kutulu. Its use of original voice acting set a standard for national studio confidence in marketing.

Moreover, it paved the way for Melnitsa’s continued expansion into interactive storytelling, including 2020 VR projects and animated shorts with AR elements.

Conclusion

Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej is not a masterpiece of game design. It is mechanically shallow, unevenly paced, and structurally limited by its time and target audience. Its combat minigames are clunky, its puzzles simplistic, and its ambition modest.

Yet, it is one of the most culturally significant games from early 21st-century Russia. It is a love letter to Slavic folklore, a testament to national media synergy, and a rare example of a licensed game that respects its source material. Its strength lies not in innovation, but in preservation.

In an era when Western games often strip mythology of context—turning myths into action-fantasy set dressing—Alyosha Popovich treats folklore as sacred narrative. It is didactic, nostalgic, and proudly local—a game that doesn’t hide its roots, but celebrates them through every frame of animation, every folk phrase, every whispered riddle.

For Western historians and folklorists, it offers a glimpse into how post-Soviet society redefines heritage. For parental nostalgia, it is a cozy trip down memory lane. For children, it is a gentle introduction to a rich mythos.

It may not have a perfect score, or a global fanbase, or a modern re-release—but in the halls of video game history, Alyosha Popovich i Tugarin Zmej stands as a definitive artifact: a game that didn’t just adapt a story, but told a nation to itself.

Final Verdict: 4/5 (Not for everyone, but essential for understanding a cultural moment.)

“It is not the strongest game that survives, but the one most responsive to its environment.”

In Russian digital folklore, Alyosha survives—because it belongs.