- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Android, DOS, OnLive, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, PlayStation, PS Vita, PSP, Windows

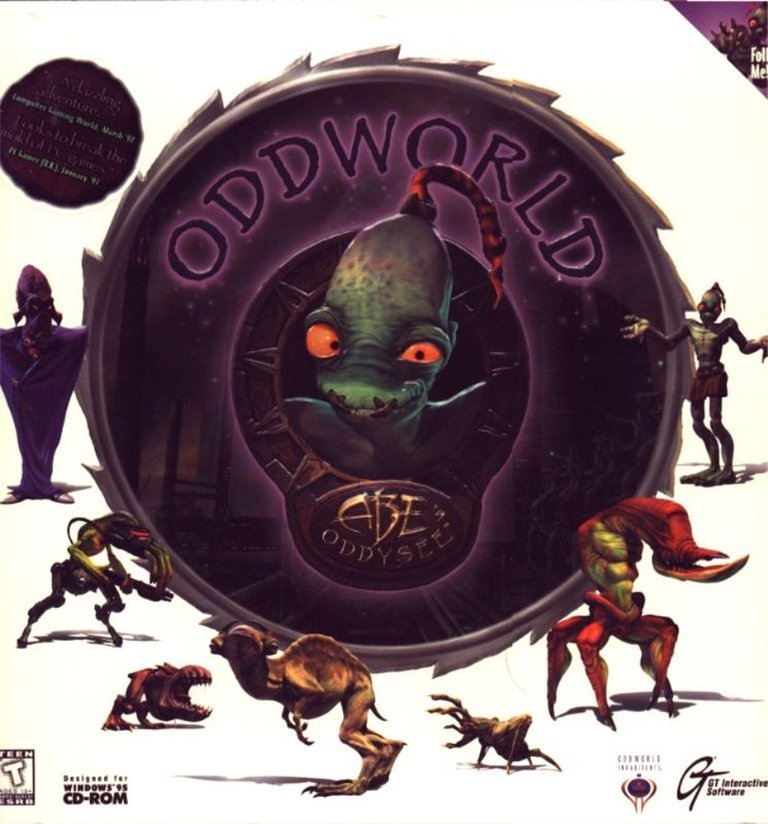

- Publisher: GameBank Corp., GT Interactive Software Corp., Oddworld Inhabitants Inc., Sony Computer Entertainment America Inc.

- Developer: Oddworld Inhabitants Inc.

- Genre: Action, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Possession, Stealth

- Setting: Cyberpunk, dark sci-fi, Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 58/100

Description

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee is a groundbreaking platformer set in a dark, cyberpunk universe. As Abe, a Mudokon slave, players discover that their race is being turned into meat by the ruthless Glukkons. Using stealth, chanting to confuse or possess enemies, and a unique communication system called Gamespeak, Abe must navigate treacherous industrial environments to rescue as many Mudokons as possible. The game’s ending changes based on the number saved, encouraging multiple playthroughs.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Free Download

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Patches & Updates

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Mods

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Guides & Walkthroughs

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (85/100): Abe also manages to remain challenging while never becoming irritating.

gamespot.com : Abe’s really is the ideal platformer, balancing its action and puzzle elements perfectly to make the game intelligent, engaging, and, best yet, fun.

retroheadz.com (84/100): Beautifully rendered, fiendishly difficult and with actual cinematic cut-scenes, this game caused a spate of bad impressions of its hero.

ign.com (7.5/100): In Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee, players take control of Abe an incredibly ugly, yet strangely compelling Mudokon slave.

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee Cheats & Codes

PlayStation

Hold R1 and enter the following at the appropriate time.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Up, Left, Right, Square, Circle, X | Abe will produce a green air mine every time he farts. |

| Triangle, Up, Circle, Left, X, Down, Square, Right | Select any sound to solve the game’s voice puzzles. |

| Down, Right, Left, Right, Square, Circle, Square, Triangle, Circle, Square, Right, Left | Level Select at the first options screen, where Abe says “Hello”. |

| Up, Right, Left, Square, Circle, Triangle, Square, Right, Left, Up, Right | Level Skip at the first options screen, where Abe says “Hello”. |

| Up, Left, Right, Square, Circle, Triangle, Square, Right, Left, Up, Right | View FMV Sequences at the first options screen, where Abe says “Hello”. |

| Circle, Triangle, Square, X, Down, Down, Circle, Triangle, Square, X | Invincibility during gameplay. |

PC

At the main menu, hold [Shift] and press the following cursor keys.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Down, Right, Left, Right, Left, Right, Left, Up | Level Select |

| Up, Left, Right, Left, Right, Left, Right, Down | View FMV Sequences |

| -it_is_me_your_father | Noclip mode. Add “-it_is_me_your_father” to your launch options, hold Shift when launching the game until Abe says “Hello” at the main menu, and press Tab during gameplay. |

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee: A Dystopian Masterpiece That Redefined Narrative-Driven Gaming

Introduction

In the crowded landscape of 1997 gaming, dominated by the rise of 3D platformers like Super Mario 64 and gritty shooters like Duke Nukem 3D, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee emerged not just as a game, but as a bold, subversive statement. Developed by fledgling studio Oddworld Inhabitants and published by GT Interactive, this cinematic platformer dared to blend brutal social commentary, ingenious puzzle design, and unparalleled artistry into a cohesive whole. As the first installment in a planned five-part “Oddworld Quintology,” Abe’s Oddysee introduced players to Abe, a humble Mudokon slave in a dystopian meat factory, tasked with escaping industrial tyranny and liberating his people. Though its punishing difficulty and technical constraints divided critics, its legacy as a landmark title—one that elevated games as a medium for storytelling and emotional depth—remains unshaken. This review dissects how Abe’s Oddysee became a cult classic, pushing boundaries in design, narrative, and world-building while cementing its place in gaming history.

Development History & Context

Oddworld Inhabitants was founded in 1994 by Lorne Lorne, a CalArts-trained animator, and Sherry McKenna, a former producer at Hollywood visual effects studio Rhythm and Hues. Their shared vision was to create a series of five interconnected games (The Oddworld Quintology) that would explore themes of corporate exploitation, environmental destruction, and cultural erasure through rich, immersive worlds. Development on Abe’s Oddysee began in January 1995 under the working title Soul Storm, later renamed Epic before settling on its final moniker in 1996 after GT Interactive acquired publishing rights.

The game’s development was a testament to ambitious, if risky, creativity. With a budget of $4 million—a staggering sum for an indie project at the time—and GT’s $10 million marketing push, Oddworld Inhabitants crafted a title that deliberately rejected the era’s obsession with 3D polygons. Instead, they pre-rendered environments and characters using high-end 3D animation tools, a choice inspired by Lorne’s background in film. This allowed for cinematic sequences that seamlessly blended with gameplay, a rarity in 1997. The team faced technological constraints, particularly limited disk space, forcing cuts to planned content like the extinct “Meech” species and a meteor shower sequence meant to symbolize Abe’s destiny.

Released on September 18, 1997, for PlayStation, DOS, and Windows, Abe’s Oddysee arrived during a pivotal moment in gaming. While 3D was ascendant, Oddworld Inhabitants championed 2D as a superior medium for storytelling and artistic control. The game’s E3 unveilings (1996 as Soul Storm, 1997 in its final form) were hailed as “showstoppers,” with critics praising its audacity. Yet, the development wasn’t without hurdles. An executive at GT Interactive attempted to sabotage the project, deeming it “not a game,” but Lorne’s conviction—and the publisher’s eventual support—saved it. This battle underscored the studio’s ethos: to create games that challenged industry norms, offering empathy over aggression and depth over spectacle.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Abe’s Oddysee is a parable of resistance against industrial capitalism, wrapped in a deceptively simple package. Abe, a Mudokon slave at RuptureFarms, stumbles upon a board meeting revealing his species’ fate: they’ll be processed into “Mudokon Pops,” a new meat snack product. The revelation—delivered through grim, cinematic cutscenes—transforms Abe from a complacent “Employee of the Year” into a fugitive, sparking a journey to free his people and dismantle Glukkon tyranny.

The narrative’s brilliance lies in its layered world-building. The Glukkons—cigar-chomping, profit-obsessed executives—symbolize unchecked corporate greed, while their Slig enforcers represent the violence of authoritarian control. Abe’s escape through RuptureFarms’ claustrophobic corridors, industrial wastelands, and ancient temples mirrors a worker’s awakening from oppression to solidarity. Even minor details carry weight: Abe’s narration, delivered with ironic detachment (“I was employee of the year once…”), contrasts the banality of factory life with the horror of his discovery.

Thematic resonance permeates every aspect. The game critiques consumerism through discontinued products like “Meech Munchies” (extinct due to overhunting), paralleting real-world ecological collapse. Rescue mechanics underscore a socialist ideal: Abe’s individual escape is insufficient; true victory requires collective liberation. The two endings—a bleak, nihilistic demise in a meat grinder if fewer than 50 Mudokons are saved, or a triumphant revolution if at least half are freed—force players to confront complicity and consequence. As one critic noted, it’s “North Korea-level sh*t,” reflecting the numbing effect of systemic oppression.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Abe’s Oddysee is a masterclass in tension-driven design, where every action carries life-or-death weight. As a physically weak Mudokon, Abe cannot fight; survival hinges on stealth, timing, and environmental manipulation. The game’s flip-screen cinematic platformer mechanics—popularized by titles like Flashback—are refined here. Abe’s movement is commitment-based: a jump or step cannot be mid-air adjusted, demanding precision. Actions like sneaking past patrols or timing jumps over meat-saw hazards create constant, pulse-raising tension.

Two systems define the experience: Chanting and GameSpeak. Chanting, Abe’s telepathic ability, stuns enemies like Scrabs and Paramites, but its most potent use is possession. By chanting near Slig guards, players can hijack their bodies, wielding machine guns and issuing commands to Slogs—a mechanic that expands puzzle-solving and subverts expectations. GameSpeak, a system of voice commands (“Hello,” “Follow me,” “Wait here”), allows Abe to coordinate Mudokon rescues, turning them from passive NPCs into active participants. Leading groups to “bird portals” requires patience and trust, as Abe can only guide one Mudokon at a time—a design choice emphasizing fragility.

Yet, the game’s mechanics are not without flaws. The checkpoint system is notoriously sparse. Death often resets players to screen starts, punishing trial-and-error progression. Critics like PC Zone noted this creates “gnashing of teeth,” as players replay sections ad nauseam. Controls, too, can feel sensitive; a slight misstep sends Abe plummeting into pits. Despite these issues, the gameplay loop—observing patterns, luring enemies into traps, and mastering possession—creates a uniquely cerebral satisfaction. As one player recalled, the “aha!” moments of solving a puzzle were worth the frustration, making Abe’s Oddysee a “spiritual experience” in its meticulous design.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Oddworld is a character in itself, a world where industrial decay and natural beauty collide. RuptureFarms, with its smoke-choked smokestacks and conveyor belts of doomed Mudokons, evokes the horrors of a Dickensian factory. In contrast, Paramonia’s overgrown temples and Scrabania’s deserts hint at a pre-industrial past desecrated by Glukkon expansion. This duality—oppression vs. heritage—is visualized through art direction that blends grotesquery with whimsy.

Pre-rendered backgrounds, inspired by claymation and industrial design, remain stunning. Textures like rusted metal and grime-drenched walls create palpable atmosphere, while character animations—Abe’s panicked scuttles, Sligs’ swaggering gait—lend personality. Even enemies are imbued with pathos: Scrabs, territorial beasts, become tragic symbols of displaced natives. The art’s power lies in its subversion; the world is alien yet familiar, a distorted mirror of Earth’s ecological and social crises.

Sound design amplifies this immersion. Josh Gabriel’s score, a melancholic blend of ambient drones and tribal percussion, underscores dread. Sound effects—dripping honey, humming machinery, Abe’s guttural chants—make the world feel alive. Voice acting, led by Lorne Lanning as Abe, is a revelation. Abe’s numb delivery (“Oh, I’m so scared…”) contrasts the Mudokons’ collective trauma, their voices flat from despair. This sonic tapestry creates a “haunting” atmosphere, as Retro Spirit noted, making every death feel visceral and every rescue cathartic.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Abe’s Oddysee was lauded as a genre-redefining achievement. Critics celebrated its “astounding graphics” (The Adrenaline Vault), “sophisticated gameplay” (Animation World Magazine), and “riveting story.” GamePro awarded it perfect scores for sound and graphics, hailing it a “PlayStation hall of fame” contender. Metacritic’s 85% aggregate score reflects near-universal acclaim, with praise for its AI-driven world and emotional depth.

Yet, the game’s difficulty polarized audiences. IGN deemed it “not for everybody,” citing its “steep learning curve,” while PC Zone criticized its “trial-and-error” design. Commercially, however, it was a juggernaut, selling 3.5 million copies by 2012—making it one of PlayStation’s bestsellers. Its legacy extends beyond sales: Abe’s Oddysee pioneered narrative integration in gameplay, influencing titles like BioShock and Inside. Its “Gamespeak” system foreshadowed modern dialogue mechanics, while its environmental storytelling set a benchmark for world-building.

The Oddworld universe expanded with sequels (Abe’s Exoddus, Munch’s Oddysee) and a 2014 remake (New ‘n’ Tasty), but none matched the original’s raw impact. Lorne Lanning’s vision of a Quintology remains unrealized, yet Abe’s Oddysee endures as a touchstone for socially conscious gaming. As Inverse noted, it taught players that games could be “so much better, but only if we try.”

Conclusion

Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee is more than a game; it’s a dystopian fable rendered in pixels and code. Its flaws—punishing difficulty, archaic controls—are undeniable, but they are outweighed by its audacity. In a market saturated with mindless violence, Abe’s Oddysee dared to craft a world where empathy was gameplay, where rescuing one Mudokon mattered, and where capitalism wasn’t just a backdrop but the villain.

Its legacy is etched in gaming history: a title that proved games could be art, challenging players to think, feel, and resist. As Abe’s journey—from slave to savior—reminds us, the most powerful revolutions often begin with the quietest voices. Abe’s Oddysee is not merely a masterpiece; it’s a testament to the medium’s potential to provoke, inspire, and endure. Verdict: Essential.