- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Sierra On-Line, Inc.

- Developer: Coktel Vision

- Genre: Special edition

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Setting: Science fiction

Description

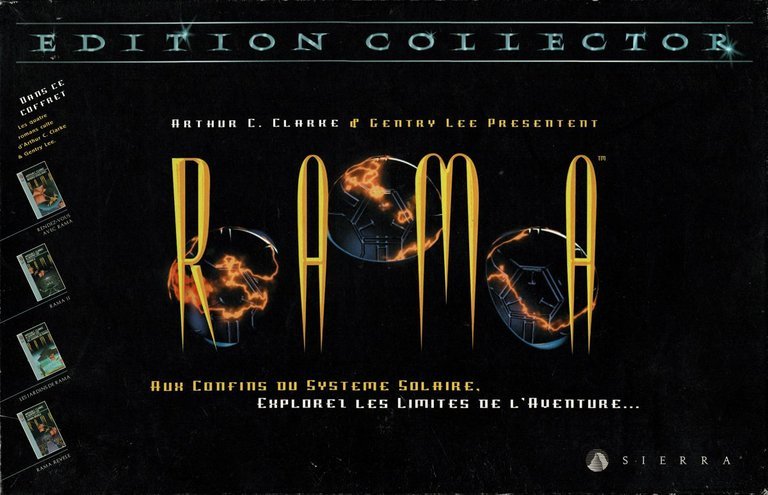

Rama (Edition Collector) is a collector’s edition exclusive to the French market that bundles the Rama adventure game with all four novels by Arthur C. Clarke and Gentry Lee. The game itself is a first-person point-and-click adventure where the player assumes the role of a replacement crew member for an expedition to investigate the mysterious interstellar spacecraft Rama. Set in a rotating cylindrical world with alien cities and creatures, players must solve logical and mathematical puzzles, interact with different alien species, and navigate the changing environment as Rama approaches Earth and the project to destroy it unfolds.

Rama (Edition Collector) Patches & Updates

Rama (Edition Collector) Guides & Walkthroughs

Rama (Edition Collector) Reviews & Reception

balmoralsoftware.com : Without the extensive backstory offered by the book series and by the characters in the game itself, Rama would still be a challenging and enjoyable entertainment.

gameboomers.com : It’s the puzzles, not the story, that drive the game.

Rama (Edition Collector): Review

Introduction

In the twilight of the 20th century, when CD-ROMs promised boundless multimedia potential, Rama (Edition Collector) emerged as a bold experiment in interactive sci-fi storytelling. More than a mere game, this French-exclusive collector’s edition—curated by Sierra France and publisher J’Ai Lu—represents a unique convergence of gaming and literature, bundling the 1996 adventure game with all four Rama novels by Arthur C. Clarke and co-author Gentry Lee. As the second adaptation of Clarke’s seminal Rendezvous with Rama saga (following a 1984 text adventure), Rama stands as a ambitious, if flawed, artifact of 1990s ambition. It immerses players in the colossal enigma of Rama, a rotating cylindrical spacecraft housing alien civilizations, blending Clarke’s cosmic wonder with Sierra On-Line’s technical prowess. Yet, despite its intellectual depth and fidelity to its source, the game was ultimately overshadowed by commercial failure and technical hurdles. This review deconstructs Rama’s legacy, dissecting its design, narrative, and impact to argue why it remains a cult classic—a testament to the untapped potential of licensed sci-fi in gaming.

Development History & Context

Developed by Dynamix, Sierra On-Line’s innovative subsidiary, Rama emerged during a pivotal era for PC gaming. The mid-1990s saw the CD-ROM revolution enabling sprawling, cinematic experiences, yet developers grappled with the constraints of hardware and design paradigms. Dynamix, known for titles like Space Quest V and Rise of the Dragon, leveraged the Sierra Creative Interpreter (SCI) engine version 3 to create a hybrid of 3D-rendered environments and live-action video—a labor-intensive process yielding 256-color graphics that pushed contemporary systems to their limits.

The game’s vision was spearheaded by Gentry Lee, Clarke’s co-author on the Rama novels, ensuring narrative authenticity. Clarke himself contributed, appearing in-game during death scenes and the epilogue, humorously interacting with the environment (e.g., provoking a Biot into combat). This collaboration aimed to translate Clarke’s themes of cosmic mystery and human curiosity into interactive form. However, Sierra’s expectations were dashed: the company projected 500,000 sales in the first three months across multiple languages, but French newspaper Libération reported only 25,000 units sold in France by November 1997, deemed “disappointing” by Sierra. The game’s three-disc structure (two for gameplay, one for video) showcased multimedia ambition, but technical instability—crashes, sound glitches, and save file limitations—marred the experience on platforms like DOS and Windows.

The French Edition Collector underscored the game’s literary roots, bundling Clarke’s novels with new cover art inspired by the game’s aesthetics. This synergy reflected Sierra’s broader strategy of cross-media adaptation, yet it arrived amid a market dominated by Myst-like first-person adventures. While Rama echoed Myst’s pre-rendered vistas and puzzle-centric design, its emphasis on narrative complexity and scientific rigor (e.g., octal/hex arithmetic puzzles) set it apart. Ultimately, unful plans for sequels—foreshadowed by the game’s epilogue—left Rama as an incomplete saga, mirroring Rama’s own unresolved mysteries.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Rama’s narrative, co-written by Gentry Lee, is a masterclass in hard sci-fi storytelling, weaving Clarke’s cosmic awe with a grounded human drama. The player assumes the role of an anonymous astronaut replacing the deceased Valeriy Borzov aboard the International Space Agency’s (ISA) Newton Team, tasked with investigating Rama—an impossibly vast cylindrical vessel that entered the solar system four years prior. The plot unfolds across three acts: exploration of Rama’s Central Plains, deciphering the alien cities of “London” and “Bangkok,” and a climactic race against time in the “New York” island within Rama’s Cylindrical Sea.

The character ensemble, ported from Clarke’s Rama II, adds depth through live-action performances. Commander David Brown (Robert Nadir) embodies leadership, while journalist Francesca Sabatini (Tiffany Helm) and engineer Richard Wakefield (Stephan Weyte) offer contrasting perspectives on the mission. Security chief Otto Heilmann (Sean Griffin) and cryptographer Michael O’Toole (Robert E. Henry) introduce moral ambiguity, hinting at espionage and paranoia. Even minor characters, like the android Puck (voiced by Kevin Donovan), serve as narrative anchors, providing exposition and wit.

Thematically, Rama explores humanity’s place in the cosmos. Rama’s scale—its cities, rotating ecosystems, and silent alien inhabitants—evokes Clarke’s signature sense of the sublime. The game’s puzzles, rooted in logic and mathematics (e.g., decoding octal sequences), mirror the scientific rigor of Clarke’s writing. Yet, it also examines hubris through the “Project Trinity” subplot, where a human faction attempts to destroy Rama, fearing the unknown. The epilogue, featuring Clarke offering philosophical advice, underscores a central tension: should we engage with the alien or annihilate it? This question resonates with Clarke’s broader oeuvre, positioning Rama as both a tribute and a standalone meditation on exploration and ethics.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Rama’s gameplay is a meticulous, if punishing, blend of exploration and intellectual challenge. Adopting a first-person perspective, players navigate pre-rendered environments using point-and-click mechanics, interacting with objects to solve puzzles and progress. The central interface is the “wristcomp,” a multifunctional device providing maps, vidmail messages, and data storage, while the android Puck offers contextual hints—a clever solution to traditional hint systems.

Puzzles are the game’s backbone, demanding mathematical fluency in non-decimal systems (octal, hexadecimal) and pattern recognition. For example, players must decode sequences like “41,43,47,53” (O’Toole’s prime-number sequence) to access areas or disarm devices. These puzzles are integrated into the narrative: activating London’s forcefield requires counting its pulses, while Bangkok’s arithmetic machines teach Raman numbering systems. However, the game’s complexity is a double-edged sword. Inventory management becomes cluttered with “red herrings” (e.g., unused symbol plaques), and randomized item locations in the Central Plains exacerbate frustration.

Technical flaws further hinder the experience. Crash-prone gameplay under DOS, sound dropouts, and save file restrictions (e.g., no special characters in names) undermine immersion. The endgame—a six-minute bomb-disarm sequence—feels rushed, lacking the buildup of earlier sections. Yet, moments of brilliance shine: the cable car ride to the base camp offers rare third-person perspective, while the Avian lair’s UV-sensitive puzzles (triggered by eating “manna melons”) demonstrate innovative design. Despite its quirks, Rama’s gameplay rewards patience, rewarding players with the thrill of solving Clarke-esque riddles.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Rama’s world-building is its crowning achievement, a faithful recreation of Clarke’s vision. The cylindrical vessel’s interior is a marvel of alien architecture: the Central Plains span vast, empty spaces dotted with enigmatic structures, while London’s gothic spires and Bangkok’s geometric monoliths evoke distinct civilizations. The game’s three cities—nicknamed by human explorers—teem with Biots (biological robots), Avians, and Octospiders, each species designed with meticulous detail. Biots like the crab-like trash collectors or crane-lifting behemoths feel like living machines, while the Octospider museum’s tripartite number wheels hint at alien logic.

Visually, Rama leverages 1990s technology to impressive effect. Pre-rendered scenes, like London’s sewage pit or Bangkok’s rainbow-colored arithmetic machines, use texture mapping and lighting to create depth. Live-action video, though compressed, captures performances with warmth—Heilmann’s paranoia, Sabatini’s journalistic ambition—grounding the sci-fi in human emotion. The color palette, limited to 256 hues, still conveys atmosphere: Rama’s sterile whites and grays contrast with the organic pinks of the avian lair.

Sound design amplifies immersion. Charles Barth’s score blends ambient synths with rhythmic motifs, evoking the tension of exploration and wonder. Sound effects—from the hum of the wristcomp to the clang of Biots—add tactile realism. Voice acting is uniformly strong, though lip-syncing issues occasionally break immersion. The French Edition Collector’s inclusion of Clarke’s novels deepens the world, allowing players to cross-reference game events with literary lore, a rare example of synergistic media integration.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Rama divided critics. Praised for its puzzles, narrative, and alien designs, it earned a 92% from PC Gamer US and was nominated for “Adventure Game of the Year” at Computer Gaming World. Keith Ferrell hailed it as “the most convincing computerized world” he’d encountered, arguing its story surpassed Myst’s setting. Next Generation concurred, noting its “decently entertaining storyline” and alien creativity. Yet, it was also criticized for its Myst-like mechanics and technical flaws. PC Gamer UK scored it 70%, lamenting its similarity to Cyan’s landmark. Commercially, it was a disappointment, with Sierra’s sales expectations unmet.

In the decades since, Rama has gained cult status among adventure game enthusiasts. It influenced later sci-fi titles, such as The Journeyman Project 3, by demonstrating how hard puzzles could drive narrative. Its legacy as a Clarke adaptation remains unmatched, blending literary fidelity with interactivity. The French Edition Collector, with its bundled novels, stands as a collector’s gem, while fan communities keep its memory alive through walkthroughs and mods. Yet, its unfinished saga—due to canceled sequels—leaves players yearning for resolution, much like Rama’s own mysteries.

Conclusion

Rama (Edition Collector) is a flawed masterpiece, a product of 1990s ambition constrained by technology and market forces. Its intellectual puzzles, faithful adaptation of Clarke’s vision, and immersive world-building place it among the era’s most ambitious adventures. While technical issues and commercial failure hindered its impact, its cult following endures, a testament to its unique synthesis of gaming and literature. For modern players, Rama offers a challenging, rewarding experience—a time capsule of when sci-fi games dared to be cerebral. In the pantheon of licensed adaptations, it stands as a noble, if imperfect, effort to translate Arthur C. Clarke’s cosmic wonder into interactive form. As Clarke himself noted in the game’s epilogue, “The Ramans always do things in threes.” While Rama never received its sequels, its legacy as a trailblazer in interactive sci-fi is undeniable—a journey well worth taking for those who seek wonder over spectacle.