- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Palladium Interactive, Inc.

- Developer: Human Code, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure, Educational, Geography, History, Religion

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Educational content, Puzzle-solving

- Setting: Ancient Greece, Historical

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

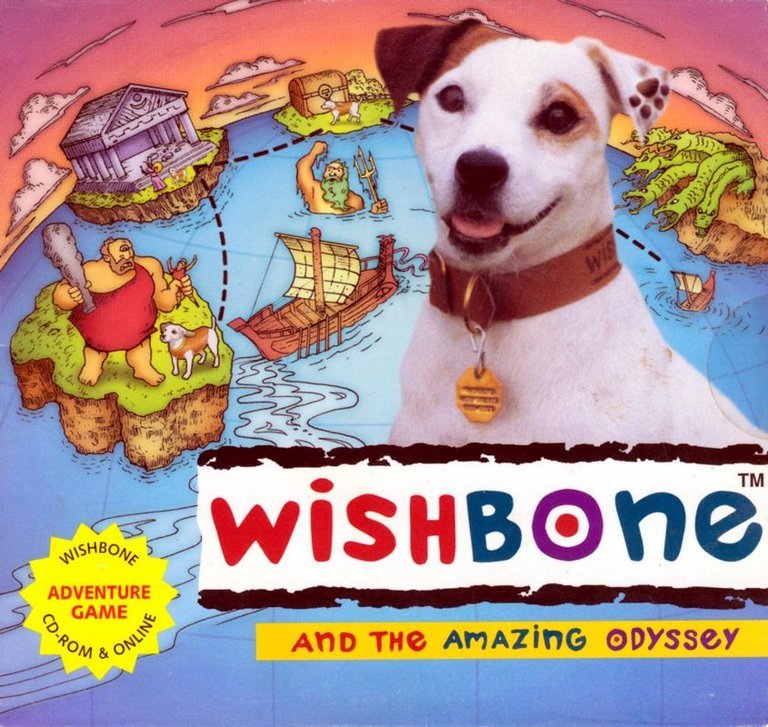

In Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey, players help the lovable Jack Russell terrier re-enact Homer’s classic tale to escape the combobulator. Navigate ancient Greece, interact with mythological characters, command your crew through challenges, and utilize the Knowledge Vault to learn about Greek mythology and history while retracing Odysseus’ epic journey.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey

PC

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey Free Download

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey Reviews & Reception

mataswemyss.blogspot.com : I found it marvelous and exciting.

myabandonware.com (86/100): This game was amazing for freshman English and the Greek mythology unit.

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey: Review

1. Introduction

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey stands as a peculiar yet fascinating artifact of 1990s edutainment, a time when CD-ROM technology promised boundless possibilities for interactive learning. Released in 1996 during the peak popularity of the PBS television series starring the erudite Jack Russell Terrier, this title transported players not just into a game, but directly into the heart of Homer’s ancient epic. The premise is deceptively simple: Wishbone, voiced by Larry Brantley, becomes accidentally trapped within an experimental “Electronic Pictographic Interactive Combobulator” (EPIC-3000) while exploring Homer’s Odyssey, forcing him to re-enact the hero’s journey to find his way back to the modern world. This review argues that despite its surface-level charm and obvious educational mandate, Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey achieves a remarkable synthesis of accessibility, narrative engagement, and pedagogical value. It successfully distills the complex, often brutal, tapestry of Homer’s epic into a format digestible for children, while preserving enough of the original’s spirit, themes of perseverance, cunning, and the clash between mortal and divine, to serve as a genuinely engaging introduction to classical mythology. Its legacy lies not in pushing technological boundaries, but in demonstrating how licensed educational properties could respect both their source material and their young audience.

2. Development History & Context

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey emerged from a specific confluence of creative and market forces. Developed by Human Code, Inc. (a studio known for innovative edutainment titles like Schoolhouse Rock!) and published by Palladium Interactive, Inc. in partnership with Big Feats! Entertainment, the project capitalized heavily on the established goodwill and recognition of the Wishbone television franchise. The game arrived in 1996, a year defined by the burgeoning potential of CD-ROMs for rich multimedia experiences. Gaming on Windows 3.1/95 and Macintosh platforms saw a surge in point-and-click adventures and educational software, titles like Myst proving the viability of CD-ROM storage for immersive worlds, while established series like Carmen Sandiego and Math Blaster dominated the edutainment space.

Human Code’s approach was distinctly collaborative and ambitious. The credits list an impressive 99 individuals, underscoring the project’s scale for its time. Key figures included Executive Producer Lisa Linnenkohl, VP of R&D and Creative Director Steven Horowitz, and a dedicated team focused on quality assurance and online features. The game utilized Macromedia Director, a common choice for multimedia CD-ROMs, allowing for rich animation, sound, and interactivity within the technological constraints of the era (primarily limited by processor speed and RAM compared to modern standards).

The creative vision was clearly constrained by the dual mandates of the Wishbone license and its educational purpose. This meant toning down the darker, more violent aspects of The Odyssey (a necessity for a PBS-branded product aimed at children) and structuring the narrative as an interactive learning tool. The challenge was balancing faithfulness to Homer with child-friendly adaptations and ensuring the educational content (the “Knowledge Vault”) was seamlessly integrated and genuinely useful, not just an afterthought. The game existed within the broader context of 90s edutainment, competing for attention against titles that often prioritized rote learning over narrative engagement, positioning Wishbone as a narrative-first gateway to mythology.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The game’s narrative framework is a brilliant act of meta-fictional adaptation. By framing Wishbone’s journey as a literal re-enactment forced upon him by the malfunctioning Combobulator, the developers cleverly sidestep the need for complex backstory justification and immediately establish the stakes: relive the epic to escape. This premise allows for liberties with Homer’s structure, most notably the significant compression of events and the merging of locations (like combining Aeolus’s island with Thrinacia) to maintain pacing and focus for a younger audience. The core plot follows Odysseus’s (Wishbone’s) journey from Troy to Ithaca, hitting all major beats: the escape from Polyphemus, the encounter with Circe, the passage past Scylla and Charybdis, the temptation of Helios’s cattle, and the return home.

Characterization undergoes significant Bowdlerization and expansion for accessibility. Polyphemus is rendered more comically threatening than terrifying; his blinding is replaced with Wishbone draping a blanket over his eye, a sequence softened by a black-out screen rather than graphic violence. Circe, while retaining her witchy allure, is portrayed as more seductively helpful than monstrously transformative. Crucially, Athena is elevated from a distant patron to a constant, guiding presence, offering the Palladium (her shield) as a tangible hint system and directly intervening to spur the reluctant Eurylochus. This character serves the dual purpose of facilitating gameplay (providing hints) and reinforcing the theme of divine favor aiding the worthy. Eurylochus, expanded from a minor figure in Homer into a near-comic relief sailor, embodies cowardice and laziness, constantly requiring prodding and providing sarcastic commentary (“Great job, Captain!”). His inclusion adds levity but also highlights the crew’s burden and Odysseus’s leadership challenge.

The most significant anachronistic addition is the enigmatic Duck. Introduced in the prologue and persistently present throughout the journey, this feathered interloper serves no purpose in the myth but becomes unexpectedly crucial for a late-game puzzle. Wishbone’s bemused comment, “Somehow, I don’t remember reading anything about a duck in The Odyssey,” perfectly captures the game’s playful, slightly irreverent tone. Thematically, the game emphasizes perseverance, wisdom over brute strength, the consequences of hubris (like eating the sacred cattle), and the enduring power of home and family. The “Knowledge Vault” reinforces the value of learning and understanding context, while the final archery contest symbolizes the proof of identity and the restoration of order. The Underworld encounter with Pluto (Hades), though non-canonical, introduces the concept of consequences and even a second chance, reinforcing the game’s ultimately hopeful and child-friendly perspective on mortality. The tragic fate of Argos, Odysseus’s loyal dog, is wisely omitted, preserving the triumphant homecoming tone.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey employs a classic point-and-click adventure interface. Players guide Wishbone through static, beautifully illustrated scenes representing key locations from the epic (Troy, Cyclops Island, Aeaea, Thrinacia, Calypso’s island, Ithaca). Interaction is primarily mouse-driven: clicking to move Wishbone, examine objects, talk to characters (via dialogue trees), and collect items into an inventory. The core gameplay loop revolves around exploration, puzzle-solving, and narrative progress.

Puzzle design is central and generally logical, integrated seamlessly with the story progression. Early puzzles involve gathering initial crew members and supplies in Troy. On the Cyclops Island, finding and using a shield to reveal a path to Polyphemus’s cave leads to the major sequence: getting the giant drunk on potent wine and escaping by clinging to the undersides of his sheep. Circe’s island presents environmental puzzles: navigating her garden, using a turkey leg to distract her wolf, and finding the protective moly herb. The most significant puzzles involve item collection and reuse: Circe’s tapestry later unlocks a door on Thrinacia, the lyre from Tiresias is used to solve a musical puzzle on the same island, and the sheep taken from Polyphemus becomes essential in the Underworld.

Mini-games provide breaks from traditional puzzles and serve key narrative functions:

1. Circe’s Checkers: A match-3 style game against the witch with pig-themed pieces. Losing here results in permanent transformation.

2. Agamemnon’s “The Trojan War”: A strategic board game in Hades where filling Troy with blue pieces against pink ones is required to win a coin.

3. Athena’s Archery Contest: The climactic puzzle in Ithaca, requiring precise alignment of axes and shields to shoot an arrow through a complex setup – fail twice, and the game ends.

4. Pluto’s Snakes and Ladders (No Ladders): A high-stakes game triggered upon Wishbone’s “death” in the Underworld, where racing to the potion of Asclepius involves avoiding numerous snakes and using coins to skip spaces on the River Styx. Declining this game results in a definitive game over.

The Knowledge Vault is a standout educational feature, accessible via an icon. It acts as an in-game encyclopedia, offering a glossary of terms, a timeline of events, character profiles, and historical/geographical context about Ancient Greece and The Odyssey. It’s designed to be consulted for clues and deeper understanding, turning gameplay into an active learning process. A flashing green indicator on the menu slab signaled when hints might be available. Character progression is minimal; Wishbone gains abilities primarily through puzzle solutions and narrative milestones, rather than traditional RPG mechanics. The UI is simple and functional, dominated by the inventory panel and the Knowledge Vault/Help icon, reflecting the era’s design sensibilities.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building masterfully balances historical authenticity with fantastical whimsy. While locations like Troy, Ithaca, and Mount Olympus are recognizable from mythology, their depiction is filtered through a bright, cartoonish aesthetic perfectly suited for children. The environments are richly detailed, albeit stylized. Cyclops Island features imposing cliffs and the giant’s cave; Aeaea is lush and mysterious with Circe’s distinctive palace; Thrinacia presents the imposing tower and the idyllic yet dangerous pasture of Helios’s cattle; the Underworld is appropriately dark and foreboding, complete with spooky castles and ominous sounds.

Art Direction: The visual style is consistent and charming. Characters are designed with exaggerated, expressive features: Wishbone retains his recognisable TV appearance, Polyphemus is a hulking brute, Circe is elegantly seductive, and the gods (when encountered, like on Mount Olympus) depicted with imposing yet approachable grandeur. The backgrounds are painterly, evoking the Mediterranean setting with vibrant blues, greens, and earth tones. The use of color and lighting effectively establishes mood – the warm glow of Aeaea versus the gloomy shadows of Hades. While not hyper-realistic, the art successfully creates a distinct, engaging, and child-friendly vision of the ancient world.

Sound Design: Audio plays a crucial role in immersion and characterization. Larry Brantley’s voice acting as Wishbone is essential, conveying the character’s wit, occasional frustration, and relatable charm. The score is atmospheric, using leitmotifs associated with locations and characters (e.g., ominous strings for Polyphemus, ethereal music for Calypso, a regal theme for Athena). Sound effects are plentiful and well-used: the crash of waves, the bellow of the Cyclops, the clink of coins, the flutter of wings, and the distinctive quack of the mysterious Duck. The Underworld is particularly enhanced by unsettling ambient noises and echoing sounds, creating a palpable sense of dread without being terrifying. The integration of sound with the point-and-click actions provides satisfying feedback. The overall soundscape successfully complements the visuals and narrative, enhancing the fantasy adventure atmosphere while remaining accessible and non-threatening to its target audience.

6. Reception & Legacy

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey received a modest but generally positive reception upon release in 1996. Critic reviews were scarce but favorable where they existed. The All Game Guide awarded it 80%, praising its challenging nature for older children and its ability to delight everyone, highlighting its successful blend of education and entertainment. However, CNET offered a more mixed verdict (“Skip It“), acknowledging its virtues – the challenging strategy games, Wishbone’s cuteness, and its educational value – but concluding these weren’t enough to overcome the “trials and tribulations” the gameplay presented, particularly for younger players. Player reviews, though limited in number (averaging 4.0/5 on MobyGames), suggest enduring fondness and nostalgia among those who played it as children, often recalling its effectiveness in teaching Greek mythology.

Commercially, the game likely performed respectably within the niche for licensed edutainment titles, leveraging the established Wishbone fanbase but probably not achieving blockbuster status. Its legacy is primarily cultural and pedagogical rather than technological or influential on mainstream game design. It stands as a quintessential example of 90s edutainment: ambitious in its scope to educate through narrative, charmingly produced, but hampered by the technological limitations and design philosophies of its era. Its primary influence lies in its success as a gateway drug to classical mythology for a generation of children. Many adult fans recall it as their first meaningful exposure to The Odyssey, sparking a lifelong interest in Homer and ancient history. Its reputation has evolved into that of a beloved “cult classic” – a nostalgic treasure for those who grew up with it and a fascinating historical artifact for game historians studying the edutainment boom. Its enduring presence on abandonware sites and the continued efforts to make it playable on modern systems (via emulators like DOSBox or custom installers) underscore its lasting appeal and the fondness it commands. While it didn’t spawn direct sequels or inspire major industry trends, its existence demonstrates the potential of licensed IP to deliver substantive educational content within engaging interactive formats.

7. Conclusion

Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey is a product of its time and place – a meticulously crafted, charming, and surprisingly faithful adaptation of Homer’s epic, filtered through the warm, educational lens of the Wishbone franchise. It succeeds brilliantly on its own terms: as an accessible, engaging, and genuinely educational introduction to Greek mythology for children. By Bowdlerizing the darker elements without trivializing the core themes of perseverance, cunning, and the perilous journey home, it creates a space where young players can experience the wonder and adventure of The Odyssey without being overwhelmed by its complexities or violence.

The game’s strengths lie in its seamless integration of narrative, puzzle-solving, and learning. The point-and-click interface is intuitive, the puzzles are logical and tied to the story, and the Knowledge Vault provides robust, contextual learning support. The characterizations, while adapted, are memorable (Eurylochus’s laziness, Athena’s guidance, Circe’s complexity), and the whimsical additions like the Duck add unique charm. The art direction and sound design create a consistent, inviting, and appropriately mythical atmosphere that enhances the experience.

Critically, its gameplay could be uneven, sometimes frustrating younger players as noted by CNET, and its reliance on 90s technology makes it inaccessible without modern workarounds. However, these flaws are minor in the context of its overall achievement. Wishbone and the Amazing Odyssey is far more than a simple licensed cash-in; it is a lovingly crafted piece of interactive literature. It stands as a testament to the potential of edutainment to be both fun and instructive, leaving a lasting legacy as a cult classic that successfully ignited curiosity in the ancient world for countless children. Its place in video game history is secure as a unique, charming, and effective example of how a classic story can be reimagined for a new generation through interactive play. It remains a delightful odyssey in its own right.