- Release Year: 2020

- Platforms: Nintendo Switch, Windows Apps, Windows, Xbox One, Xbox Series

- Publisher: CIRCLE Entertainment Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: 1970s, France

- Average Score: 64/100

Description

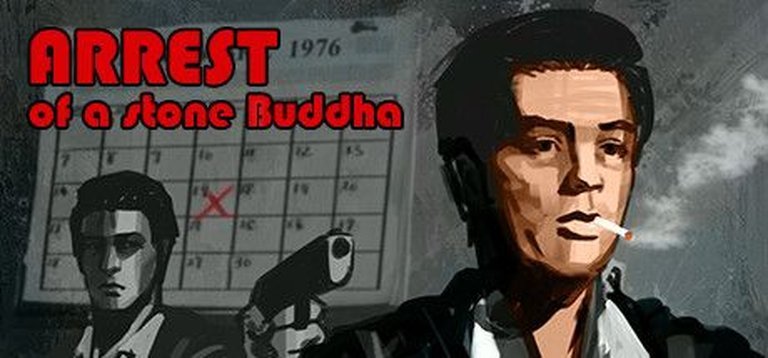

Set in 1970s France, ‘Arrest of a Stone Buddha’ is an existential action shooter where you play as a member of a radical group trapped in an unending cycle of violence. As days blend into each other, the meaningfulness of your actions fades, leaving only a bitter quest for fleeting purpose amidst societal chaos. The game explores themes of meaninglessness and the futility of violence through its bleak narrative and challenging gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Arrest of a Stone Buddha

PC

Arrest of a Stone Buddha Cracks & Fixes

Arrest of a Stone Buddha Guides & Walkthroughs

Arrest of a Stone Buddha Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (64/100): It’s an unrelentingly bitter game, one which has the power to incite a strong reaction in anyone who plays it.

nintendoworldreport.com (65/100): All in all, those looking for something light on exposition and direction but heavy on senseless violence and lonely wandering may find a worthwhile experience here.

waytoomany.games : I think this is the perfect case of a game in which its themes and message were crafted with a higher degree of priority than its gameplay loop.

Arrest of a Stone Buddha: Review

Introduction

In the landscape of contemporary video games, where spectacle and accessibility often reign supreme, Arrest of a Stone Buddha emerges as a stark, uncompromising anomaly. Developed by Moscow-based creator Yeo and released in 2020, this side-scrolling shooter is less a conventional game and more a visceral, meditative experience on the nature of violence, time, and existential despair. As the second entry in Yeo’s “Existential Dilogy”—following The Friends of Ringo Ishikawa and preceding Fading Afternoon—it crystallizes the developer’s singular vision of stripping interactive entertainment to its philosophical core. This review argues that Arrest of a Stone Buddha is a flawed yet audacious masterpiece of digital minimalism, a work that transcends gameplay conventions to deliver a haunting, unforgettable critique of modern consciousness. Its brilliance lies not in its mechanics, but in its unflinching exploration of meaninglessness, making it a polarizing landmark in indie game history.

Development History & Context

Arrest of a Stone Buddha was created by Yeo, a Russian developer whose previous work, The Friends of Ringo Ishikawa (2018), established a reputation for blending pixel-art aesthetics with existential themes. Released on February 27, 2020, for Windows, with subsequent ports to Nintendo Switch (May 21, 2020) and Xbox platforms (May 14, 2021), the game was developed using the Game Maker engine—a choice that underscores its indie roots and technical constraints. Yeo’s vision was deliberately minimalist, influenced by French New Wave cinema (Jean-Pierre Melville, Louis Malle) and John Woo’s balletic gunplay. This cinematic fusion is evident in the game’s structure, which alternates between hyper-stylized shootouts and mundane daily routines.

The 2020 gaming environment saw a surge of indie games grappling with artistic ambition, yet Arrest of a Stone Buddha stood apart for its radical rejection of player agency. Yeo explicitly sought to create a “game about nothing” in the spirit of Seinfeld, using Paris, 1976, as a backdrop to dissect the tedium and violence of modern life. The developer’s background as a Russian artist also informs the game’s bleakness, reflecting a cultural perspective on alienation and existential inertia. Despite critical division, the game became a cult phenomenon, praised by discerning critics for its daring vision but criticized for its deliberate design choices that prioritize thematic immersion over player satisfaction.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Arrest of a Stone Buddha is a narrative of paralysis. Set over the 30 days leading to a November 1976 deadline, it follows a nameless contract killer navigating the cyclical despair of his existence. The plot unfolds in stark vignettes: missions begin with the cold execution of a target (e.g., a retired soldier in a church), followed by a desperate escape through waves of enemies. Between hits, the player roams a decaying Parisian city, visiting a bar, pharmacy, cinema, or lover’s apartment—activities devoid of purpose or consequence.

The game’s dialogue is sparse and cryptic, confined to conversations with the protagonist’s handler, a former military comrade who ruminates on art, talent, and futility. The handler’s admission that he was rejected from art school (“they said I had no talent”) mirrors the protagonist’s own creative impotence, while fleeting mentions of a deceased comrade, Ranky, hint at unresolved guilt. The lover’s apartment is a particular enigma; here, the protagonist sits silently on a bed beside a figure (presumed female) who never moves or speaks, embodying the emptiness of human connection.

Themes permeate every pixel: the title itself is a metaphor for the protagonist’s “arrest” by time and circumstance. He is a “stone Buddha”—immobile, unenlightened, trapped in a cycle of violence and monotony. The game’s structure mirrors Buddhist concepts of Dukkha (suffering), as the player is forced to endure repetitive, meaningless actions. Whether violence robs life of meaning or life’s meaninglessness drives violence remains deliberately ambiguous, inviting players to project their own interpretations onto this bleak tableau. As Digitally Downloaded noted, it’s “an unrelentingly bitter game” that forces confrontation with existence’s futility.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Arrest of a Stone Buddha defies traditional game design, dividing its time between two distinct modes that clash yet complement each other thematically.

Combat Sections: These side-scrolling shootouts are defined by claustrophobic intensity. Missions begin with the target’s execution, after which enemies spawn infinitely from screen edges. The protagonist moves at a glacial pace, and his health is minimal, requiring precise, methodical progress. Combat revolves around weapon disarming (X key) and shooting (C+Z), with no ammo counter or HUD. Players must visually track bullets, forcing improvisation as they scavenge weapons from defeated foes. Three enemy types persist: pistol-wearing grays, shotgun-wielding blacks, and snipers. The latter often attack off-screen, a design choice that exacerbates frustration but also reflects the game’s “unseen threats” motif. Controls are intentionally sluggish—movement feels weighted, and disarming requires proximity—heightening the sense of vulnerability. Success demands patience, but the cycle of death and repetition often devolves into tedium.

Daily Life Sections: These interludes are defined by absence. Players navigate a small Parisian district (apartment, pharmacy, bar, cinema) performing mundane actions: sitting, drinking, watching films (represented by projected light), or buying sunglasses. Time passes relentlessly, with days blurring into one another. Sleeping pills can skip nights, but they’re finite, emphasizing the inescapability of routine. There are no quests, no stats, no currency—only the passage of time. This segment is deliberately boring, a critique of “objective-driven” gaming. As NamuWiki notes, “The daily parts except the battle are very boring, so the important point is how to spend time until the next battle.”

The game’s minimalism extends to progression. No levels or skills improve the protagonist; he remains a “fast and lucky” killer whose only evolution is psychological. This design reinforces the narrative’s themes: agency is an illusion, and existence is a predetermined cycle. While innovative, the mechanics polarized players. Way Too Many Games lamented that “its actual gameplay loop is so clunky and frustrating,” while Digitally Downloaded argued the jank served the themes, creating “a sense of naked vulnerability.”

World-Building, Art & Sound

Yeo’s Paris, 1976, is a character in itself—a city rendered in muted, pixelated hues of gray, sepia, and olive. The art style evokes French New Wave films, with stark architectural backdrops (churches, high-rises, bars) and detailed character animations. Famitsu specifically praised the “detailed animations,” particularly the protagonist’s dual-pistol reloads, which mirror John Woo’s balletic choreography. The pixel art is intentionally crude, emphasizing texture over detail, making the world feel tangible yet alien.

Sound design reinforces the atmosphere. The soundtrack features minimalist MIDI compositions—Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes No. 1 recurs during moments of existential dread—while gunshot effects are crisp and unforgiving. Ambient sounds (traffic, rain) are sparse, amplifying the protagonist’s isolation. The bar’s clinking glasses and the cinema’s projector hum are rare moments of “life,” yet they feel mechanical. This sonic minimalism mirrors the game’s themes: even in crowds, the protagonist is alone.

The world-building is subtle but profound. The cinema’s unseen films, the lover’s static figure, and the handler’s art-school allusions create a tapestry of unfulfilled potential. As Mr. GeckoBiHu (in Backloggd) observed, the museum’s “unrecognizable” paintings turn players into “beings-in-art,” blurring the line between observer and participant. It’s a world where beauty and decay coexist, mirroring the protagonist’s fractured psyche.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Arrest of a Stone Buddha divided critics, earning a Metacritic score of 64 (Mixed or Average) based on four reviews. Praise centered on its artistic ambition: Digitally Downloaded awarded it 90%, calling it “a triumph” for its emotional impact, while Otaku Gamers UK (80%) hailed it as “a rare and beautiful case.” Famitsu highlighted the animations, and TouchArcade deemed it a “one-of-a-kind experience” for niche audiences.

However, criticism focused on gameplay. Noisy Pixel (50%) and Way Too Many Games (50%) cited “cheap deaths” and “confusing mechanics,” arguing the daily sections felt “pointless” due to combat frustrations. Nintendo World Report (65%) compared it unfavorably to Ringo Ishikawa, noting it was “more dour and less varied.” Player reviews were equally divided, with some hailing its genius and others dismissing it as “pretentious.”

Commercially, the game underperformed, becoming a cult favorite among arthouse gamers. Its legacy lies in its influence on experimental indie design. Yeo’s follow-up, Fading Afternoon (2023), expanded on these themes, while games like Katana Zero adopted its minimalist storytelling. The title also sparked academic discourse, with Mr. GeckoBiHu’s analysis comparing its “duration” to artist Tehching Hsieh’s performance art. Yet, its reputation remains that of a polarizing work—a game that “incites a strong reaction,” as Digitally Downloaded noted, whether love or loathing.

Conclusion

Arrest of a Stone Buddha is a game that defies easy categorization. It is not fun in the traditional sense; it is not polished, and it does not reward skill with satisfaction. Instead, it offers something rarer: a profound, disquieting meditation on the human condition. Yeo’s creation succeeds artistically by transforming gameplay into philosophy—turning a shooter’s chaos into existential dread and a city’s streets into a prison of routine.

While its clunky mechanics may alienate players seeking escapism, they are inseparable from its vision. The slow-walking protagonist, the silent lover, the infinite enemies—these are not flaws but tools for immersion in a world devoid of meaning. As a historical artifact, Arrest of a Stone Buddha stands as a testament to video games’ potential as a medium for introspection. It is a flawed masterpiece, a stone Buddha frozen in time, challenging players to confront the void within themselves. For those willing to endure its bleakness, it is a triumph—a game that lingers long after the credits roll, a digital echo of existential despair that is, in its own way, beautiful.