- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

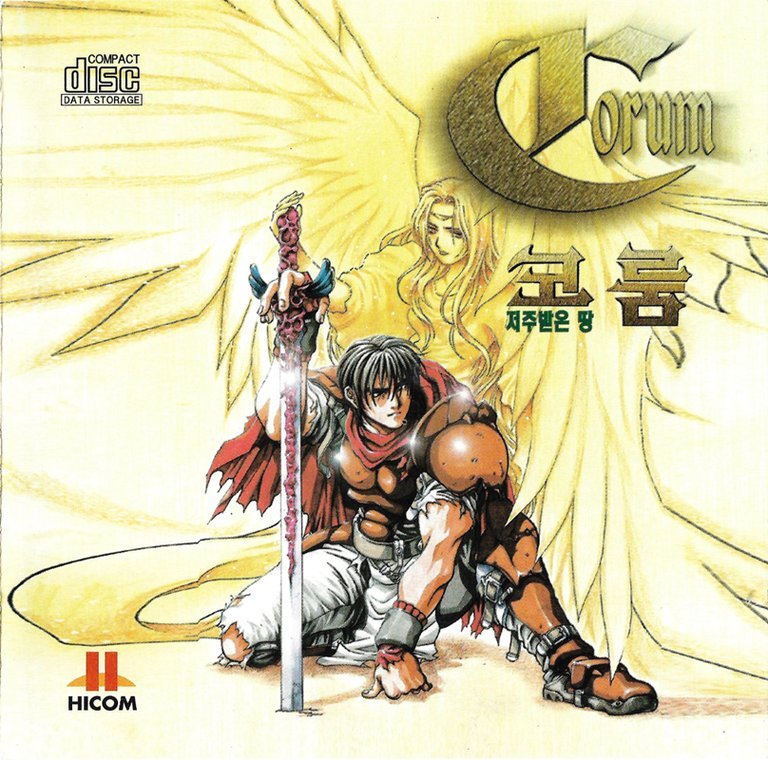

- Publisher: Hicom Entertainment

- Developer: Hicom Entertainment

- Genre: Action, Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Action-based combat, Experience points, Gold, Multiple weapon types, Weapon proficiency

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 55/100

Description

Corum: Jeoju Badeun Ttang is a Korean-made action role-playing game set in a medieval fantasy world. The game follows Beat, a warrior seeking revenge after his village was destroyed by a demonic warlord. In this action-driven RPG, players navigate vast wilderness areas and engage enemies using a combination of regular attacks, blocking, and dashing attacks. With three weapon types (swords, halberds, and bows), each with unique fighting styles and proficiency levels, players can tailor their combat approach as they earn experience and gold.

Corum: Jeoju Badeun Ttang Reviews & Reception

vgtimes.com (55/100): The main publisher of the game is Hicom Entertainment.

Corum: Jeoju Badeun Ttang: Review

Introduction

In the annals of Korean gaming history, few titles embody the ambition and growing pains of a nascent industry as vividly as Corum: Jeoju Badeun Ttang (The Cursed Land). Released in April 1997 by HiCom Entertainment, this action RPG emerged during a transformative era when South Korean developers were carving out a distinct identity in the global PC market. Though overshadowed internationally by contemporaries like Diablo, Corum established itself as the third-most popular RPG series in its homeland after The War of Genesis and Astonishia Story. Yet, its legacy is a study in contrasts: a foundational work whose technical flaws and simplistic design both defined the limitations of its time and paved the way for its critically acclaimed sequels. This review dissects Corum’s intricate layers—from its tumultuous development to its innovative combat system—to argue that beneath its unpolished exterior lies a landmark piece of Korean game design, flawed yet undeniably influential.

Development History & Context

HiCom Entertainment, founded in 1988, began as a distributor for Sega and Samsung consoles before pivoting to software development in the mid-1990s. By 1997, the company was one of Korea’s most prolific studios, but Corum’s creation was fraught with challenges. The game was developed internally by HiCom’s “Saver Team,” led by director Misoon Yu and game designer Seungwook Choi, with a core of 16 programmers, artists, and sound designers. Technologically constrained by the mid-1990s PC landscape, the team built a custom engine for 2D scrolling gameplay with diagonal-down perspective, optimized for Windows 95’s limited graphics capabilities.

The Korean gaming industry of 1997 was a David-versus-Goliath scenario. While Western RPGs dominated global markets, Korean developers sought to blend local storytelling with accessible action mechanics. Corum epitomized this ambition, aiming to create a “Korean answer” to console action RPGs. However, the 1997 IMF crisis severely impacted HiCom, forcing bankruptcy that June. Remarkably, the studio rebranded as HiCom Entertainment just two months later, surviving through sheer will to publish Corum’s ambitious sequel in 1998. This context explains the game’s rushed production: assets were reused across projects (Still Hunt and Gaegujangi Kkachi), and the team prioritized scope over polish, resulting in a title that felt both innovative and incomplete.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Corum’s narrative follows a time-honored fantasy trope: the revenge of Beat, a warrior whose village is annihilated by demonic forces led by the warlord Anpnentria. The plot unfolds through sparse dialogue and environmental storytelling, with Beat traversing interconnected screens to confront increasingly monstrous minions. Unlike its sequels, Corum offers no deep lore or character arcs; Beat is a silent protagonist, his motivation distilled into a single, primal drive for vengeance. The narrative’s thematic core—cyclical violence and the futility of rage—is undercut by simplistic execution. Villains lack compelling backstories, and townsfolk exist as static quest-givers, their dialogue functional yet devoid of depth.

What little thematic nuance emerges is subtle: the “cursed land” of the title suggests a world irrevocably tainted by war, yet this is never explored beyond surface-level evil. The game’s most poignant thematic element lies in Beat’s isolation. As the sole survivor of his village, his journey is a lonely pilgrimage through hostile wilderness, mirroring the player’s own solitary exploration. Though underdeveloped, this thread of existential isolation anticipates the darker, more mature narratives of later entries like Corum III. Ultimately, Corum’s story serves as a vehicle for gameplay rather than a standalone experience, reflecting the era’s prioritization of mechanics over narrative immersion.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Corum’s gameplay is a double-edged sword: ambitious in its action-RPG fusion but hampered by execution flaws. The core loop involves Beat traversing interconnected screens—from deserts to forests—fighting enemies to earn experience and gold. Combat is real-time and action-oriented, featuring three moves: a standard combo, a dashing attack, and an active block. Each weapon type (sword, halberd, bow) has a unique fighting style, with proficiency levels rising through repeated use—a precursor to skill-based progression in modern RPGs.

However, the combat system reveals critical weaknesses. The block mechanic is counterintuitive, often leaving Beat vulnerable instead of defensive, encouraging players to dodge and button-mash. Enemy AI is rudimentary, with minions attacking predictably and bosses alternating between laughably easy and nigh-invincible phases that demand excessive grinding. The bow, intended for ranged combat, is rendered practically useless due to poor hit detection. A curious “power bar” that recharges between attacks, inspired by Final Fantasy Adventure, adds a layer of strategy but feels underutilized.

Character progression is minimalist. Beat gains stats through leveling, but equipment upgrades are sparse, and the UI clunky. The interconnected world design, while innovative for its time, suffers from repetitive enemy placement and maze-like layouts. Despite these flaws, Corum’s core mechanics laid groundwork for its sequels, which refined combat into a more dynamic, satisfying experience.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Corum’s world is a patchwork of medieval fantasy archetypes, rendered in a distinctive 2D style. Environments—from scorched villages to labyrinthine dungeons—are detailed with hand-drawn textures, though the aesthetic leans toward “plastic charm,” as noted by HG101, with character models exhibiting a stiff, doll-like quality. The diagonal-down perspective provides a clear view of the battlefield but sacrifices atmospheric depth, making locales feel sterile rather than immersive.

Sound design is similarly functional. Gong Ryong Studio’s soundtrack consists of repetitive MIDI tracks that fail to evoke emotion, while sound effects (clashing swords, monster roars) are serviceable but unremarkable. The absence of voice acting or dynamic audio underscores the game’s budget constraints. Yet, the art direction possesses a unique cultural identity. The character designs, by Hangjea Choi, blend Western fantasy tropes with Korean sensibilities, evident in Beat’s ornate armor and the bestiary’s grotesque demons. This visual fusion, coupled with the game’s top-down perspective, created a blueprint for Korean action RPGs, balancing accessibility with a sense of place.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Corum was a moderate success in Korea, praised for its ambitious scope but criticized for its rough edges. Contemporary reviews (sparse in English-language archives) highlighted its combat innovations while lamenting its AI and grind. Its legacy, however, evolved over time. As the first entry in a trilogy, it set the stage for Corum II: Dark Lord (1998) and the masterful Corum III: Chaotic Magic (1999), which refined mechanics, added party systems, and introduced superior storytelling.

Internationally, Corum remained obscure, though its influence persisted. The series’ evolution from a flawed experiment to a polished RPG demonstrated HiCom’s growth, which culminated in MMOs like Dragon Raja. Corum also highlighted the challenges of Korean game development in the 1990s: resource scarcity, technical constraints, and the struggle to compete with global giants. Today, it is remembered as a curio—abandonware preserved on platforms like the Internet Archive—yet its core ideas (weapon proficiency, interconnected worlds) echo in modern action RPGs. As HG101 notes, Corum III may be Korea’s finest single-player ARPG, but it could never exist without its imperfect progenitor.

Conclusion

Corum: Jeoju Badeun Ttang is a relic of a bygone era, a game that mirrors the ambitions and limitations of 1990s Korea. Its narrative is threadbare, its combat unbalanced, and its art inconsistent. Yet, it is also a testament to creative resilience. HiCom’s Saver Team, working under duress, forged an action RPG that blended local aesthetics with global trends, laying groundwork for one of Korea’s most enduring series. While Corum stands in the shadow of its successors, it remains a vital artifact—an imperfect but earnest attempt to define Korean identity in interactive media. For historians and genre enthusiasts, it is not just a game to be played but a story to be studied: the story of how ambition, even when flawed, can carve a path toward greatness.