- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: United Software Entertainment AG

- Developer: Virtual X-citement

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Puzzle

- Setting: Jungle, Mars, Orient, Seabed

- Average Score: 45/100

Description

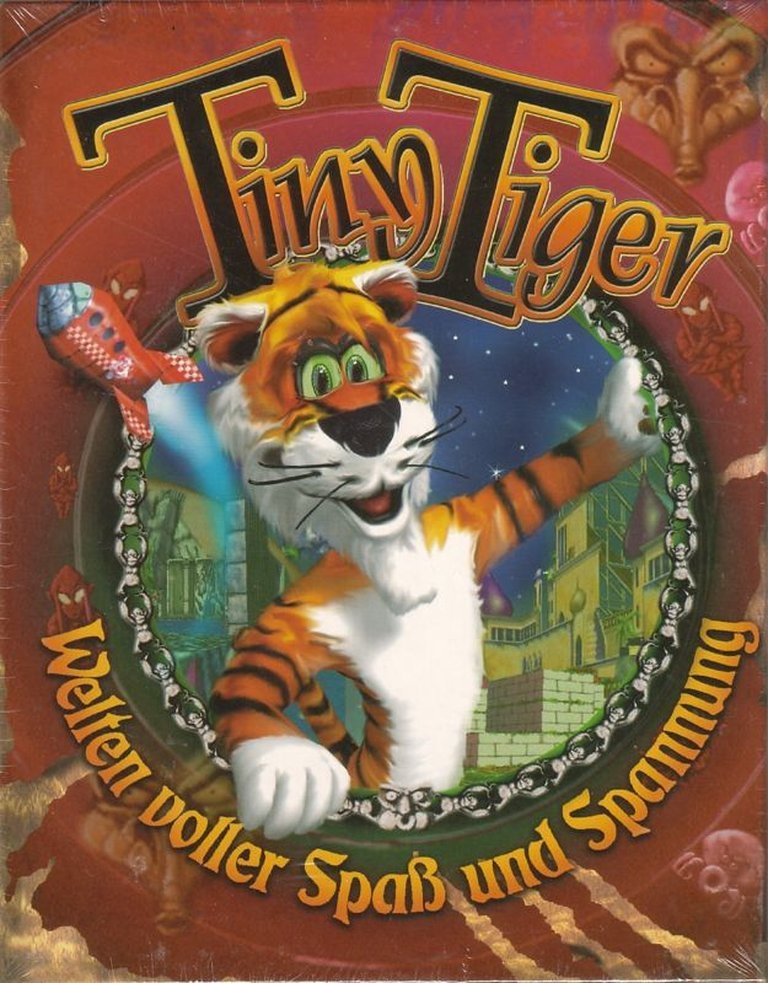

Tiny Tiger is a 1999 Windows game combining platform action and puzzle-solving. Players control Tiger Tom on a quest to rescue his friend Whoofy from the villainous King Rüdiger. Explore 40 levels across four diverse worlds: Jungle, Orient, Seabed, and Mars. Each level challenges you to find hidden keys by solving Sokoban-style block-pushing puzzles and navigating treacherous platform sections. Utilize power-ups like time bombs and masks to overcome enemies and obstacles. Developed by Virtual X-citement and published by United Software Entertainment AG.

Gameplay Videos

Tiny Tiger Patches & Updates

Tiny Tiger: A Curious Artifact of Late-90s German PC Gaming

Introduction:

Released in 1999 amidst the burgeoning 3D revolution, Tiny Tiger emerges as a largely forgotten curio—a German-developed, CD-ROM-based action-platformer with puzzle mechanics, published by United Software Entertainment AG. Controlling the determined feline hero Tiger Tom on a rescue mission against the villainous King Rüdiger, the game promised vibrant worlds and engaging challenges. Yet, critically panned for imprecise controls and dated presentation, it faded into obscurity. This review argues that Tiny Tiger serves as a valuable historical artifact, illuminating the ambitions and limitations of niche European developers during a turbulent era in PC gaming. Its legacy lies not in acclaim, but in its documentation of the fragmented, highly localized strategies required to survive in the late-90s market.

Development History & Context:

Virtual X-citement, the Berlin-based developer behind Tiny Tiger, was a small studio operating on the fringes of the booming German gaming scene. Founded by Stefan Piasecki, who handled concept and project leadership, the team comprised nine individuals, including art lead Uwe Meier and programmer Nico Schmidtchen. Their experience was largely collaborative: Meier, Vlček, and Novak worked together on Metro-Police and Tiny Trails, suggesting a focus on accessible, family-friendly 3D action games.

Technologically, Tiny Tiger utilized an in-house 3D engine—a common choice for indie teams avoiding licensing fees from major middleware providers. Windows 95-era graphics, while competent for platforming, were constrained by the hardware realities of 1999: limited polygon counts, basic textures, and unremarkable character animation. The game’s CD-ROM format reflects a transitional phase—just before digital distribution made physical media obsolete.

Culturally, Tiny Tiger arrived as German developers sought to carve out spaces beyond the console-dominated industry. The USK 0 rating signified its target of children and families, positioning it against Disney-published platformers and local hits like Welt der Wunder. Its dual title (Tiny Tiger: Welten voller Spaß und Spannung) underscores aggressive regional marketing—a necessity for survival in a market flooded with imports.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive:

The plot is intentionally simplistic: Tiger Tom’s friend Whoofy is kidnapped by King Rüdiger. Tom’s journey through four themed worlds—Jungle, Orient, Seabed, and Mars—frames the rescue as a linear quest. While dialogue is sparse, the narrative relies on environmental storytelling: enemies (lizards, mechanical foes) populate hostile landscapes, and collectibles like time bombs or masks hint at a chaotic, playful menace.

Themes of friendship and perseverance emerge through gameplay rather than exposition. Tom’s transformation from petrified victim to resourceful rescuer is conveyed through player actions—overcoming obstacles, defeating enemies, and saving allies. However, the story lacks depth or moral ambiguity. King Rüdiger’s motives remain unexplored, reducing the conflict to a generic hero-vs-villain trope. The game’s “fun” ethos (Spaß und Spannung) prioritizes immediate engagement over narrative sophistication.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems:

Tiny Tiger blends Sokoban-style puzzles with platforming precision. Each of the 40 levels tasks players with locating hidden keys via block-pushing mechanics, requiring spatial reasoning. Platforming sequences demand pixel-perfect jumps, with gaps and hazards testing reflexes.

Strengths:

– Innovative Puzzle Integration: Sokoban variants provide intellectual challenges distinct from reflex-based platforming.

– Item Utility: Time bombs eliminate enemies, while masks induce confusion—adding strategic depth.

– Level Variety: Four worlds offer shifting aesthetics (e.g., aquatic caves on Seabed, futuristic traps on Mars).

Flaws:

– Unforgiving Controls: Critics noted “unprecise steering” (PC Games Germany), penalizing players with excessive deaths.

– Linear Progression: Doors often require sequential key solves, limiting exploration.

– Character Animation: Uwe Meier’s work suffered from stiff motions, reducing fluidity during jumps or attacks.

The absence of multiplayer or save systems further limited replayability, relegating the experience to short, single-session playthroughs.

World-Building, Art & Sound:

The four worlds evoke distinct atmospheres: the lush, vibrant Jungle contrasts the eerie, dimly lit Seabed; the Orient’s pagodas and lanterns shift to Mars’ metallic ruins. Art direction leans into primary colors and cartoonish designs, prioritizing clarity over realism. Environments are functional—each puzzle or platforming section is visually distinct but repurposes assets frequently.

Sound design is functional yet forgettable. Christian Kirsch’s music incorporates light orchestral motifs per world (e.g., exotic percussion in Orient). Sound effects are minimal: block pushes lack weight, and enemy deaths lack impact. Compared to contemporaries like Rayman 2 or Crash Bandicoot (whose music defined their worlds), Tiny Tiger feels generic and underdeveloped.

Reception & Legacy:

Upon release, Tiny Tiger received poor critical reception—averaging 35% across two German critics. PC Player (Germany) praised its “non-exceptional” charm, while PC Games (Germany) condemned its controls as unsuitable even for children. Commercially, the game was marginal; few records survive beyond its CD-ROM distribution.

Its legacy is that of a footnote. Design elements (Sokoban puzzles + platforming) influenced later hybrid titles, but Tiny Tiger itself left no direct lineage. The studio’s subsequent projects (Tiny Trails) adapted its formula for broader audiences, yet none matched the obscurity of its debut. The game remains a cultural artifact: evidence of Germany’s vibrant indie scene in the 1990s—a time when small teams navigated piracy, fragmented retail, and console dominance to publish niche titles.

Conclusion:

Tiny Tiger is not a masterpiece. Its controls are flawed, its narrative shallow, and its visuals dated. Yet, it remains significant as a documented effort by European indie developers to innovate within constraints. Virtual X-citement harnessed 3D engines and puzzle mechanics to create an accessible, if imperfect, platformer. For historians, it exemplifies the risks and creativity of post-reunification German gaming—a world where studios like theirs pushed boundaries despite limited resources. While forgotten by most, Tiny Tiger endures as a time capsule: proof that not every game needed global acclaim to make history.

Final Verdict:

Tiny Tiger is a noteworthy curiosity, not a classic. Its historical value outweighs its entertainment merit, offering insights into the ambitions of late-90s European PC gaming. Collectors and historians may find it intriguing, but players seeking polished experiences should look elsewhere. Score: 3.2/10 (Historical Significance: 7/10 | Gameplay: 3/10 | Innovation: 5/10)