- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: GT Interactive Software Corp.

- Developer: Zombie LLC

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: LAN

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 63/100

Description

ZPC is a first-person shooter set in a sci-fi/futuristic world where you play as a god-king awakened from suspended animation to confront an evil sect that has overrun the planet. The game features industrial music by The Revolting Cocks and controversial theological imagery, with the protagonist depicted as a dark, moody messianic figure. Developed by Zombie LLC and released in 1996, it blends action-packed gameplay with a unique, edgy aesthetic.

Gameplay Videos

ZPC Free Download

PC

ZPC Reviews & Reception

gaslightandsteam.com : ZPC is an example of how a game with all the right elements can fail to come together in a satisfying fashion.

justgamesretro.com : It’s unlikely anyone would remember ZPC if it weren’t for its art style, which remains absolutely unique to this day.

ZPC Cheats & Codes

PC

During gameplay, hold down Ctrl and type one of the following codes. For level select, hold Alt + Esc when starting a New Game.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| tetsuo | Enables God Mode (invincibility) |

| ack | Restores health/Oxygen |

| psion | Provides all weapons with full ammo |

ZPC: Review

Introduction

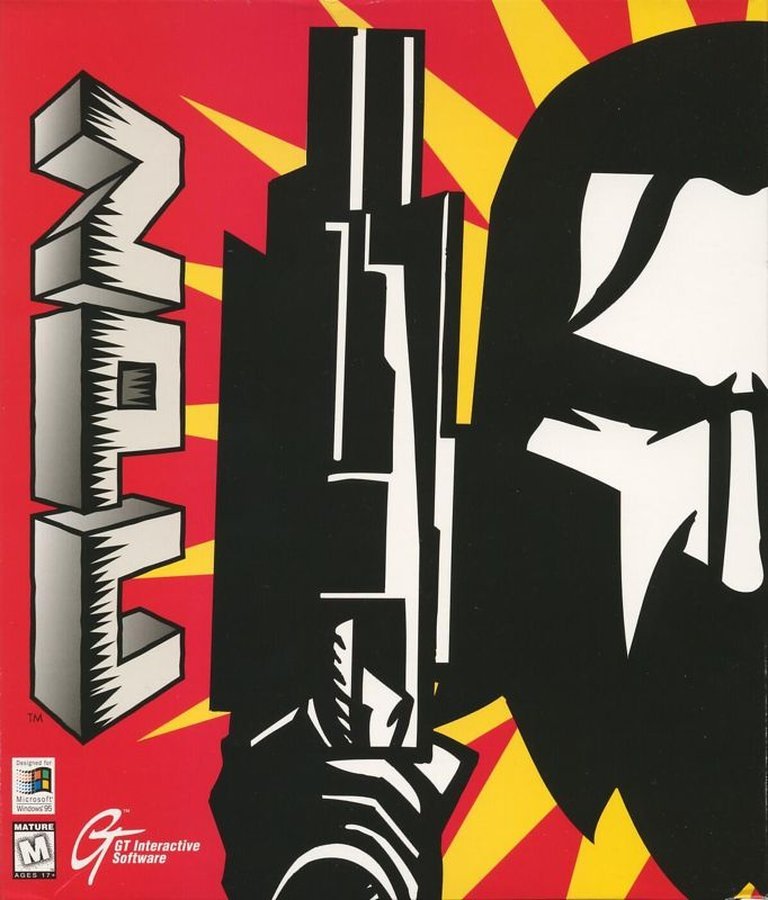

In the crowded pantheon of 1990s first-person shooters, where titans like Doom, Quake, and GoldenEye 99 dominate the historical narrative, titles like ZPC (Zero Population Count) often reside in the shadowy margins – obscure, maligned, yet intensely fascinating. Developed by Seattle-based Zombie LLC and published by GT Interactive in December 1996, ZPC arrived amidst a torrent of competing FPS offerings. Its unique visual identity, forged by renowned industrial artist Aidan Hughes (of KMFDM fame), promised a departure from the norm. Yet, despite its striking aesthetic and intriguing premise, ZPC largely vanished from mainstream consciousness upon release. This review posits that ZPC is far more than a mere footnote; it is a profoundly ambitious, artistically audacious, and deeply flawed artifact that represents a bold, albeit ultimately compromised, attempt to elevate the FPS genre beyond its visceral roots. Its legacy lies not in commercial success or gameplay innovation, but as a testament to a specific, rebellious moment in gaming history, where counter-culture aesthetics collided with the technical limitations of the era.

Development History & Context

ZPC emerged from the crucible of mid-1990s game development, a period defined by the explosive growth of the PC gaming market and the burgeoning dominance of the first-person shooter genre. Zombie LLC, founded in 1984 and primarily known for flight simulators and military simulations like the early Spec Ops titles, stepped into this high-octane space with a distinctly unconventional vision. The development budget, noted to be less than $1 million, was modest compared to the escalating costs of AAA titles like Quake.

The game’s technological foundation was the Marathon 2 engine, licensed from Bungie. While a capable engine for its time, known for its support for both Macintosh and Windows platforms and features like network play and a complex scripting system for storytelling (as seen in Marathon itself), it was not without its constraints. As contemporary reviews and retrospectives keenly observed, the engine’s capabilities were visibly strained by ZPC‘s artistic ambitions. Its sprite-based rendering, while allowing for the distinctive, pre-rendered 2D art assets, struggled with complex 3D spaces. The physics felt “floaty,” navigation was often awkward (especially with stairs and elevators), and the overall pace felt sluggish compared to the faster, more fluid offerings like Quake.

The core creative vision was driven by Artist Aidan Hughes, who is credited not only with the visual style and concept but also as Director and Story writer. Hughes, famous for the stark, provocative, and politically charged propaganda-style artwork associated with KMFDM and other industrial acts, sought to inject a similar raw, confrontational energy into interactive entertainment. This ambition was underscored by the involvement of music producers Roland Barker and Paul Barker, also known as Al Jourgensen and Piggy from Ministry/Revolting Cocks, promising an equally potent aural experience. The game was released simultaneously on Macintosh and Windows, targeting the then-thriving Mac gaming community as much as the PC mainstream. Its release in December 1996 placed it in direct competition with holiday juggernauts, contributing to its commercial obscurity despite its critical polarization.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, ZPC presents a deceptively simple yet thematically rich narrative: the return of the exiled savior. The player assumes the role of Arman, a fourth-generation “Warrior Messiah” awaken from a century-long cryogenic sleep. His mission is to liberate the planet from the tyrannical grasp of the Black Brethren, a fascist cult whose rise to power involved the violent overthrow of a once-prosperous Republic. The story unfolds primarily through dynamic, comic book-style cutscenes between levels, illustrated in Hughes’ signature woodcut style – stark blacks, dramatic reds, and a raw, almost visceral energy.

The narrative deliberately layers potent, often controversial themes. The protagonist, nicknamed “The Messiah,” is visually depicted as a neo-classical Jesus figure – dark, moody, and armed to the teeth. This “Crystal Dragon Jesus” trope, as noted by TV Tropes, immediately establishes a complex fusion of messianic duty and violent retribution. His followers are loyal but desperate emaciated figures, akin to Marathon’s hapless BOBs (Bob’s Big Bodyguards), often finding themselves in gruesome peril (e.g., trapped in food processing machines).

The antagonists, the Black Brethren, embody pure, unadulterated evil. Clad in imposing red uniforms or sleek aristocratic suits, they are explicitly compared to Nazis in promotional materials. Their control is absolute, enforced through omnipresent propaganda broadcasts and brutal repression. The game explores themes of genocide (the Brethren actively seek to eliminate Arman’s followers), omnipotence (the player possesses immense power and faces the moral weight of its consequences), and corrupted authority (the Brethren represent the perversion of order and faith). The narrative structure itself reinforces these themes, particularly through sequences that force player choice. Home of the Underdogs highlights a key example: entering a room with starving followers and a mysterious machine. Activating the machine reveals it as a horrific processing device, graphically crushing the worshippers. This moment isn’t just shock value; it’s a deliberate, brutal illustration of the consequences of violence and indifference, forcing the player to confront the results of their actions in a way few FPS games dared at the time. The struggle to reclaim Arman’s “Psionic crown” and unite his followers becomes a metaphor for restoring a fractured world order against nihilistic tyranny.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Underneath its unique aesthetic lies gameplay firmly rooted in the established FPS template established by Doom and refined by Quake, but with several distinct, and often contentious, mechanical twists powered by the Marathon 2 engine.

- Core Loop & Combat: The fundamental loop involves navigating labyrinthine levels, fighting enemies, finding keys (“W” doors for ammo, other colored doors for progression), and solving rudimentary environmental puzzles (flipping switches, opening doors). Combat is the primary focus. The player wields the “Johnny 7,” a multifaceted weapon that transforms based on ammunition: starting as a pistol, evolving into a machine gun, shotgun, grenade launcher, an electromagnetic rail gun, and finally a vaporizer. Ammo is scarce and must be rationed carefully, forcing strategic choices.

- Health System: A significant departure from the norm is the health system. Defeated enemies consistently drop health orbs. These orbs range from light blue (minor restoration) through dark blue (major boosts), allowing the player’s health to exceed its default maximum – a crucial survival mechanic given the game’s difficulty. However, this generosity is counterbalanced by the high damage dealt by enemies, often up to 75% per strike later in the game, creating a frantic “health rollercoaster” as players must constantly engage to replenish resources.

- The Chi Punch: Perhaps the most unique and divisive mechanic is the “Chi Punch,” replacing the traditional jump function. This psychokinetic orb is used for:

- Jumping: Looking down at the ground and activating the punch propels the player backward, allowing for significant jumps (and exploiting the engine’s physics for shortcuts). This is often essential for navigating environmental hazards and reaching secrets.

- Interaction: Hitting distant switches, moving objects, and activating doors.

- Combat: Pushing enemies back.

- Execution is cumbersome, requiring precise aiming downwards and timing, especially under fire. Many reviews noted this as a major source of frustration, breaking the flow of combat and exploration. It relies heavily on the Marathon engine’s physics, which some found “floaty” and inconsistent.

- Saving & Progression: Saving is restricted. Players must find and collect “Memory Orbs” scattered throughout the levels. Each save consumes one orb. This enforced scarcity forces caution and careful resource management but is widely criticized as an archaic and punitive mechanic, especially for players accustomed to quicksave.

- Engine Quirks & Level Design: As a Marathon 2 derivative, the game inherits its engine’s limitations:

- Physics: Movement can feel sluggish. Stairs and elevators are notoriously awkward to navigate, often causing the player to get stuck or “fall” through geometry. Water hazards are present but feel clunky.

- Level Design: Levels are often described as abstract mazes rather than coherent spaces. Navigation relies heavily on the automap, which can be confusing. Later levels introduce complex teleportation networks, hidden doors, and “impossible” architecture, potentially leading to frustration and backtracking. Enemy teleportation is used frequently for ambushes, sometimes perceived as cheap.

- Targeting: Can be imprecise, particularly over distances or across complex geometry.

In essence, ZPC‘s gameplay is defined by a tension: the desire for fast-paced, visceral combat clashes with the engine’s inherent sluggishness and the deliberate friction introduced by mechanics like the Chi Punch and save orbs. It demands patience and perseverance more than reflexes.

World-Building, Art & Sound

ZPC‘s world-building is inseparable from its art and sound design; the aesthetic is the narrative and atmosphere.

- Visual Design (Aidan Hughes): The game’s defining feature is Hughes’ artwork. Every screen, character, enemy, prop, and cutscene is rendered in his signature style: stark, high-contrast black-and-white line work with strategic, often jarring, uses of red. The aesthetic draws heavily from Soviet and Chinese propaganda posters, underground comics, and religious iconography. Character designs are grotesque yet symbolic: the Black Brethren’s foot soldiers evoke jackbooted fascists, the “cowardly bureaucrats” skulk in shadows, dominatrix-like figures represent perversion, and the Brethren leaders themselves are monstrous. Environments are bleak industrial wastelands, oppressive urban zones under lockdown, and surreal abstract spaces. The world feels oppressive, decaying, and charged with ideological conflict. The lack of texture variety and the sometimes inconsistent use of sprites (where a texture might function as a wall in one area and a door in another) are technical limitations acknowledged by critics, but the overall impact remains visceral and memorable. The cutscenes, presented as dynamic comic panels, are particularly lauded for their effectiveness in advancing the plot and establishing tone.

- Sound Design & Music (Roland Barker & Paul Barker): The auditory experience, driven by the Barkers, is equally integral. However, its implementation was a point of contention. Music does not play continuously over levels. Instead, it’s often triggered programmatically within the environment, playing short, looping clips that emanate from “propaganda speakers.” This creates a disorienting effect: combat might be accompanied by a martial beat in one area, while another sequence unfolds in near-silence. Critics like Gaslight & Steam noted the lack of pervasive music hampered atmosphere, while others felt the localized, sometimes repetitive, tracks added to the oppressive, industrial soundscape. Sound effects are robust and impactful – weapon fire, enemy cries, Chi Punch impacts, and the horrific crunch of the processing machine. The overall soundscape contributes significantly to the game’s grim, tense, and often disturbing tone. The involvement of the Revolting Cocks promised an industrial edge, and while the full band’s presence might be subtle beyond the intro track, the music and sound undeniably carry that signature abrasive, mechanical weight.

The synergy between Hughes’ oppressive visuals and the Barker’s industrial soundscaping creates a unique, cohesive, and unforgettable world that transcends the technical limitations of its engine. ZPC feels less like a traditional game world and more like stepping inside one of Hughes’ nightmarish, politically charged illustrations brought to life.

Reception & Legacy

ZPC‘s reception upon release in late 1996 was deeply polarized, mirroring its gameplay and artistic dichotomies. The Macintosh version fared notably better, with Mac Gamer and Mac Game Gate awarding it 92% and 80% respectively, praising its unique atmosphere, art, and intensity. Game Freaks 365 (Windows) also lauded it highly at 92%, calling it an overlooked gem that deserved more attention than Blood.

Conversely, several prominent publications were harsh. CNET (40%) and GameSpot (36%) were particularly scathing, with GameSpot infamously suggesting it should be left shrink-wrapped as a collector’s item of a “good concept gone terribly wrong,” citing confusing level design, poor controls, and repetitive gameplay. Computer Games Magazine (40%) felt it lacked the polish and innovation of competitors. Power Play (German) gave it a dismal 14%, criticizing the engine’s lameness and design flaws. The average critic score was a lukewarm 63%, with significant variance between platforms and publications.

Player reviews collected later (MobyGames, Backloggd) lean slightly negative, averaging 3.4/5, reflecting enduring frustration with the gameplay hurdles. However, a dedicated cult following emerged, particularly among fans of Marathon, industrial music, and underground art, drawn to its uncompromising style and thematic daring.

Legacy and Evolution: ZPC did not spawn sequels or directly imitate major franchises. Its legacy is more subtle but significant:

- Artistic Ambition in FPS: It stands as a landmark for artistic ambition within the genre, deliberately prioritizing a unique, cohesive visual and aural identity over pure technical polish or derivative mechanics. It prefigured later games that used strong visual styles as a core pillar (e.g., some entries in the Serious Sam series, Spec Ops: The Line‘s narrative critique, though tonally very different).

- Niche Cult Classic: Its obscurity and flaws paradoxically solidified its status as a cult title. For those willing to endure its quirks, it offers an experience unlike anything else from the era. It’s frequently cited in discussions of overlooked or underrated gems.

- Zombie Studios’ Identity: While known for military sims later, ZPC represented a bold, experimental phase for Zombie LLC, showcasing their willingness to tackle unconventional projects.

- Aidan Hughes’ Portfolio: It remains a significant entry in Hughes’ body of work, translating his distinctive artistic vision into an interactive medium.

- Technical Time Capsule: It serves as a fascinating artifact of the mid-90s transition between generations of FPS technology, showcasing the capabilities and limitations of engines like Marathon 2 when pushed beyond their original design.

- Unrealized Potential: The announced (but never materialized) film adaptation highlights the perceived strength of its core concept and world-building.

While ZPC didn’t revolutionize the industry, its legacy endures as a courageous, flawed, and deeply personal vision – a testament to the creative risks that sometimes produce the most memorable artifacts in gaming history. Its reputation has slowly shifted from merely “flawed” to “bravely unique,” appreciated by retro-gaming communities and historians for its unapologetic counter-culture spirit.

Conclusion

ZPC is a profoundly ambivalent masterpiece – a game simultaneously crippled by its technological constraints and elevated by its uncompromising artistic vision. On one hand, its gameplay is a frustrating relic of the FPS’ formative years, hampered by the sluggish physics and awkward navigation of the Marathon 2 engine, the cumbersome Chi Punch mechanic, the punitive save system, and often confusing level design. It demands a tolerance for archaic design choices that many modern players will find insurmountable. On the other hand, its artistic and thematic execution is genuinely extraordinary. Aidan Hughes’ stark, propaganda-inspired visuals create a world of oppressive dread and visceral impact that remains unique. The narrative, though simple on the surface, tackles complex and mature themes – genocide, the morality of power, corrupted faith – with disturbing effectiveness, particularly in sequences forcing player complicity. The industrial soundscape, despite its uneven implementation, provides a relentlessly oppressive atmosphere. It is a game where the ambition to convey the consequences of violence feels shockingly mature for the era.

ZPC ultimately fails as a pure action game but succeeds, in a deeply flawed way, as an interactive work of art. It stands as a vital, if flawed, counterpoint to the glossy, increasingly sanitized mainstream FPS of the late 90s. Its place in video game history is secured not by its sales or direct influence, but by its sheer, unrepentant originality and its willingness to court controversy and artistic risk. It is a challenging, often infuriating, but ultimately unforgettable experience – a cult classic for a reason. For the patient player willing to look beyond its dated mechanics, ZPC offers a glimpse into a rebellious, artistic spirit that dared to ask what a first-person shooter could be, beyond just a shooting gallery. It is a flawed monument to a specific, creative moment, and its legacy is one of audacious, if imperfect, brilliance. Verdict: A flawed, audacious, and essential cult classic best experienced with patience and appreciation for its uncompromising artistic vision.