- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Scott Adams

- Developer: Scott Adams

- Genre: Adventure, Compilation

- Perspective: Text-based

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Interactive fiction, Text adventure

- Setting: Fantasy, Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

The Scott Adams Collection is a compilation of classic text-based adventure games originally developed for early home computers like the Apple II and TRS-80. This collection includes 13 interactive fiction games, such as Adventureland and Pirate Adventure, which have been ported to modern systems using the ScottFree interpreter. The games are shareware, allowing players to enjoy them freely with optional donations, and span a variety of fantasy and sci-fi settings.

The Scott Adams Collection Reviews & Reception

giantbomb.com : ’tis but a barren wasteland

The Scott Adams Collection Cheats & Codes

TI-99/4A

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| POKE 26831,169 | No Opponents |

| POKE 27028,0 | None |

| POKE 31005,12 | None |

| POKE 21006,221 | None |

| MNRN | Access area 1 |

| HLXD | Access area 2 |

| KMVJ | Access area 3 |

| TVJO | Access area 4 |

| OBZD | Access area 5 |

| KMNV | Access area 6 |

| LMVL | Access secret area |

The Scott Adams Collection: Review

Introduction

To step into “The Scott Adams Collection” is to journey back to the primordial dawn of interactive storytelling—a time when video games were not yet visual spectacles but collaborative conversations between player and machine. Released in 1997, this compilation is far more than a mere archive; it is a digital time capsule preserving the foundational work of Scott Adams, the undisputed pioneer of commercial text-based adventure games. While Adams shares a name with the Dilbert cartoonist, his legacy is etched in the history of computing, not syndication panels. This collection, lovingly curated and preserved by Adams himself, bundles 13 of his earliest games—from the revolutionary Adventureland (1978) to the Marvel-licensed The Hulk—into a single package, accessible via the ScottFree interpreter. Its significance lies in its role as both a portal for modern players to experience gaming’s infancy and a testament to the ingenuity of an era constrained by kilobytes of memory. Yet, this review argues that the collection’s true value transcends nostalgia: it is a vital artifact documenting the birth of interactive fiction, the commercialization of home computing, and the fragile, audacious spirit of the garage-developer. As we explore its contents, we uncover not just games, but blueprints for the entire interactive entertainment industry.

Development History & Context

The story of “The Scott Adams Collection” begins with Scott Adams himself, a systems programmer for Stromberg Carlson who, in 1978, purchased a TRS-80 Model I with a paltry 16KB of RAM. Inspired by the DEC mainframe game Colossal Cave Adventure, Adams envisioned recreating its magic on a microcomputer—a feat deemed impossible by peers. Undeterred, he conceived a radical solution: an interpreter that separated game logic from data, enabling multiple adventures to run on minimal hardware. His first creation, Adventureland, was a triumph of compression and ingenuity, selling for $14.95 via magazine ads and mailed cassette tapes. This nascent success prompted Adams to co-found Adventure International (AI) in 1979, one of the first dedicated video game companies, with his wife Alexis Adams serving as co-designer on titles like Pirate Adventure.

The technological constraints of the era defined the series. The TRS-80’s tape drives required 20-minute load times, while its limitations necessitated a rigid two-word verb-noun parser (e.g., “GET CROWN”). Adams and his team meticulously ported the interpreter across platforms—Apple II, TI-99/4A, Commodore PET—expanding AI’s reach. By 1982, AI repackaged the games as SAGA (Scott Adams Graphic Adventures), adding rudimentary visuals as hardware evolved. Yet, the company’s ambition outpaced its stability. A lucrative 1983 deal with Marvel Comics for the Questprobe series—featuring licensed characters like the Hulk—led to overextension. When the home computer market collapsed (TI dumped its TI-99/4A stock, Commodore faltered), AI’s $3 million in sales couldn’t stave off bankruptcy in 1985. Adams’ poignant recollection—“The worst was when we had to close the doors. Bankruptcy is a very painful process”—underscores the brutal cost of innovation.

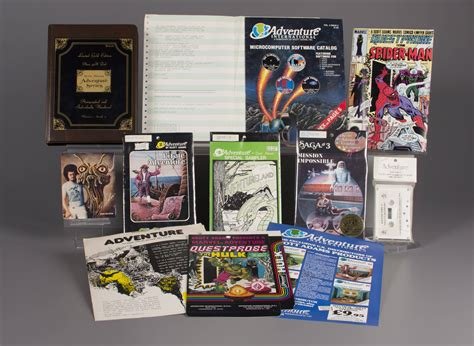

“The Scott Adams Collection” emerged as a digital resurrection. Released in 1997, it bundled the original text-only versions of Adams’ classics (not the SAGA remakes) with the ScottFree interpreter, a reverse-engineered program created by enthusiasts to preserve the games on modern systems. Paul David Doherty’s Windows port ensured accessibility, while Adams’ freeware/donationware model (“contribution is strictly voluntary”) reflected his philosophy of preserving gaming heritage. The collection thus bridges two eras: the analog tape-trading culture of the late 1970s and the digital distribution boom of the late 1990s, embodying a rare act of stewardship from an industry pioneer.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The 13 games in this collection are microcosms of early interactive fiction, each a self-contained world defined by its puzzles and lore. Adams’ narratives are lean, functional, and evocative, relying on atmospheric descriptions and verb-driven immersion rather than cinematic storytelling. Adventureland (1978), the series progenitor, is a straightforward treasure hunt through a cave system, echoing Colossal Cave but streamlined for home computers. Its legacy lies in establishing the parser-centric template: players navigate with compass directions (N, S, E, W) and interact via commands like “OPEN DOOR,” with puzzles requiring lateral thinking (e.g., using a lamp to solve darkness sequences).

Subsequent titles expand thematic diversity. Pirate Adventure (1979), co-designed by Alexis Adams, introduces mission-oriented gameplay beyond treasure-seeking: players must build a ship to reach Treasure Island, blending resource management with exploration. This mechanic—replacing cumulative scores with “do-or-die” objectives—becomes a hallmark of later games like The Count (vampire hunting) and Voodoo Castle (escape-themed). Strange Odyssey (1979) ventures into sci-fi, with players stranded on a planet and repairing a spaceship, while Mystery Fun House (1979) leans into whimsy with carnival-themed puzzles. The two-part Savage Island (1980–1981) is an early example of serialized storytelling, requiring players to complete both parts to win, a precursor to episodic content.

The Marvel tie-in, The Hulk (from the Questprobe series), stands apart. Its narrative is tied to comic lore, with players controlling the Hulk to rescue the Fantastic Four—a design choice that prioritized brand synergy over originality. Thematically, the games reflect Adams’ sci-fi fandom (over 3,000 books in his collection) and love for pulp fiction. Settings range from gothic castles (Voodoo Castle) to haunted towns (Ghost Town), unified by a sense of isolation and discovery. Dialogue is sparse, replaced by environmental storytelling: a “cryptic message” or “glowing runes” imply deeper lore, inviting players to piece together narratives through exploration.

Yet, the narratives are ultimately secondary to puzzle design. Adams’ games are celebrated for their logic, but solutions often border on the obscure—requiring players to guess verbs like “TIE ROPE” or “SAY MAGIC WORD.” This reflects the era’s design ethos: puzzles were meant to be solved, not narratively justified. As Stephen Granade notes in Brass Lantern’s history, Adams’ work was “frustrating but compelling,” a trade-off of immersion for challenge.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, “The Scott Adams Collection” is a masterclass in minimalist design, powered by a deceptively simple system. The parser, a two-word engine (verb-noun), was a revolutionary compromise for 16KB machines. It recognized commands like “GET KEY” or “EAST DOOR,” rejecting complex syntax. While this streamlined input, it also created frustration: players could type “ATTACK DRAGON” but not “SLAY DRAGON,” demanding lexicon memorization. The ScottFree interpreter modernizes this with copy-paste functionality, but the underlying logic remains.

Gameplay revolves around three loops: exploration, puzzle-solving, and inventory management. Movement grid-based, with compass directions guiding players through static, room-by-room locales. Inventory is limited, encouraging strategic item use—e.g., combining “LAMP” and “OIL” to create light. Puzzles fall into archetypes: environmental (e.g., aligning stars in Strange Odyssey), item-based (building a ship in Pirate Adventure), and logical (decoding cryptograms in The Count). Innovation lies in their structure; Pyramid of Doom (not included here but part of the series) introduced timed elements, while Savage Island part two required completing part one, creating narrative continuity.

Character progression is absent—players are a blank slate—emphasizing puzzle mastery over stats. This aligns with Adams’ vision: adventures as “mental gyms,” not RPGs. The UI, in its original form, was austere: a text prompt and a response window. The ScottFree port adds niceties like font resizing and save states, but preserves the stark, command-line aesthetic. Flaws are evident: parser ambiguity (“what do you want to open?”), unwinnable states (e.g., dropping a critical item), and mazes (Ghost Town’s graveyard) that feel like padding. Yet, these quirks are inseparable from the collection’s charm—they are not bugs, but features of a bygone design philosophy.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Adams’ games are worlds built from text, where atmosphere springs from lexical artistry. Voodoo Castle’s “damp stone corridors” and Savage Island’s “jungle canopy” evoke vivid settings through evocative nouns and verbs. The absence of graphics forces players to internalize locales, transforming descriptions into mental maps—a process Stephen Granade terms “cinematic imagination.” This is most potent in Mystery Fun House, where carnival sounds are suggested by text alone: “You hear a clown’s laugh echoing.”

Artistically, the collection is a study in contrasts. The original games were text-only, but the SAGA series (excluded here) added primitive static images. The Scott Adams Collection deliberately omits these, preserving the purity of the parser experience. The ScottFree interpreter’s monochrome text window feels intentionally retro, with block fonts and no embellishment. It is a digital parchment, inviting players to fill in the blanks.

Sound is nonexistent in the originals—cassette tapes offered no audio cues. The collection similarly abandons audio, relying entirely on text. This silence amplifies the games’ isolation: in Adventureland, the only “sound” is the parser’s terse responses. Yet, this absence is a strength; it focuses attention on the narrative, making each “You die” or “You found the treasure” a punctuation mark in the player’s unfolding story. As the Museum of Play highlights, Adams’ work thrived on constraint: “Without graphics, the imagination becomes the canvas.” The collection’s aesthetic is thus one of radical minimalism, proving that atmosphere can thrive in the spaces between words.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Scott Adams’ games were revolutionary. Adventureland sold 50+ copies to a single Radio Shack manager, and Byte Magazine’s 1980 feature on Pirate Adventure cemented Adams as a visionary. Adventure International’s peak in 1983—$3 million in sales, CES appearances in a Hulk suit—reflected mainstream acclaim. Yet, critiques emerged: players lamented parser limitations and obscure puzzles. Alexis Adams’ contributions, like co-designing Voodoo Castle, were underappreciated in an era dominated by male developers.

The 1997 collection arrived in an industry transformed. By then, graphical adventures (e.g., Myst) dominated, and text games were seen as quaint relics. Reception was muted; MobyGames lists no critic reviews, and Grouvee’s single user rating (2/5) dismisses it as a “barren wasteland.” Yet, its legacy evolved. The ScottFree interpreter became a cornerstone of the interactive fiction community, preserving Adams’ work for platforms he never imagined. The Strong Museum’s acquisition of Adams’ archives—original packaging, code, and marketing—highlights its historical value. As the Museum notes, his collection “documents early commercial computer gaming,” from cassette tapes in bottle liners to limited gold editions with certificates of authenticity.

Influence is undeniable. Adams’ interpreter model inspired developers like Infocom, while his two-word parser set standards for accessibility. The collection’s freeware ethos foreshadowed modern open-source preservation. Today, it is revered by historians and purists—a Rosetta Stone for understanding how games transitioned from mainframes to homes. As Brass Lantern’s history concludes, “Adventures refused to be forgotten,” and this collection ensures that legacy endures.

Conclusion

“The Scott Adams Collection” is more than a game; it is a fossil, a manifesto, and a love letter to the roots of digital storytelling. Its games are artifacts of a time when a 16KB machine was a playground, and a two-word command could spark a universe. For modern players, it is a challenging, often frustrating journey into a bygone design ethos—one that prioritizes parser puzzles over graphics and imagination over spectacle. Yet, its flaws are its virtues. The parser’s ambiguity isn’t a bug; it’s a dialogue. The lack of graphics isn’t a limitation; it’s an invitation to co-create worlds.

Historically, the collection is irreplaceable. It preserves Scott Adams’ audacious leap from mainframe to microcomputer, the rise and fall of Adventure International, and the unsung contributions of designers like Alexis Adams. It proves that gaming’s first golden age wasn’t defined by polygons, but by prose and persistence. In an era of billion-dollar budgets, this collection is a humbling reminder that innovation thrives in constraints.

Ultimately, “The Scott Adams Collection” earns its place in history not as a “fun” game by modern standards, but as a foundational text. It is the Genesis chapter of interactive fiction, and for historians, preservationists, and adventurers, it remains an essential pilgrimage. As Adams himself might say: “If you’re unable or unwilling to ‘play’ these games, you may still freely learn from them.” And in that learning lies their enduring power.