- Release Year: 1990

- Platforms: Genesis, Windows

- Publisher: MediaKite Distribution Inc., Renovation Products, Inc., SEGA Enterprises Ltd., Tec Toy Indústria de Brinquedos S.A.

- Developer: ITL Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Boss battles, Scrolling shooter, Shield, Transforming mech, Weapon charging

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

Arrow Flash is a side-scrolling space shooter set in a sci-fi universe where players control a female spaceship pilot on a mission to save Earth from an evil dragon attacking from another galaxy. Navigating vertically or horizontally through levels, players avoid or destroy enemies while confronting boss battles at each stage’s end. The game features a unique dual-form system: players can switch between a spaceship equipped with destructive lasers and a robot capable of raising a protective shield and instantly killing enemies. Arrow Flash special attacks are charged via button-holding or collected icons for strategic deployment.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Arrow Flash

PC

Arrow Flash Free Download

Genesis

Arrow Flash Mods

Arrow Flash Guides & Walkthroughs

Arrow Flash Reviews & Reception

segadoes.com : Arrow Flash has many faults, but its greatest might be the poor implementation of an otherwise solid concept.

en.wikipedia.org (61/100): Arrow Flash received mixed reviews.

howlongtobeat.com (74/100): Overall it’s a classic.

mobygames.com (61/100): It controls very well and has the virtue of not being too impossibly hard for younger players.

Arrow Flash Cheats & Codes

Sega Genesis

At the options menu, switch the setting ‘Arrow Flash’ from ‘Stock’ to ‘Charge’. After the story demo, wait for the gameplay demo, then press Start to begin the game. Now, when you hold C for five seconds, you’ll be invincible for about 10 minutes.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| Hold C for 5 seconds | Invincibility for ~10 minutes |

| 9WET-AGSG + XLET-AAHJ | Start with 100 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + R0ET-AAHJ | Start with 75 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + LCET-AAHJ | Start with 50 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + E0ET-AAHJ | Start with 25 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + ECET-AAHJ | Start with 20 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + C0ET-AAHJ | Start with 15 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + CCET-AAHJ | Start with 10 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + ALET-AAHJ | Start with 2 lives |

| 9WET-AGSG + AGET-AAHJ | Start with 1 life |

| RFLT-A6WA | Infinite lives |

| ALGA-AA36 | Invincibility |

| CCWT-AAGR | Start with 16 arrow force shots |

| BWWT-AAGR | Start with 12 arrow force shots |

| BCWT-AAGR | Start with 8 arrow force shots |

| A4WT-AAGR | Start with 6 arrow force shots |

| ALWT-AAGR | Start with 2 arrow force shots |

| AGWT-AAGR | Start with 1 arrow force shots |

| ACWT-AAGR | Start with no arrow force shots |

| R07A-A6VT | Infinite arrow force shots |

| CG7A-BJV8 | Robot arrow flash lasts 2x as long as normal |

| CG7A-BNV8 | Robot arrow flash lasts 3x as long as normal |

| CG7A-BTV8 | Robot arrow flash lasts 4x as long as normal |

| CG7A-B2V8 | Robot arrow flash lasts 6x as long as normal |

| CG7A-BAV8 | Robot arrow flash lasts 8x as long as normal |

| AJCA-AAB2 | Start on stage 2 |

| ANCA-AAB2 | Start on stage 3 |

| ATCA-AAB2 | Start on stage 4 |

| AYCA-AAB2 | Start on stage 5 |

| AW7A-AA3T | Infinite Special Weapons |

Arrow Flash: Review

Introduction

In the golden age of 16-bit scrolling shooters, few games dared to innovate so boldly yet faltered so completely as Arrow Flash. Released in October 1990 for the Sega Genesis by developer ITL Co. Ltd. and publishers Sega (Japan/EU) and Renovation Products (US), this horizontal shoot-’em-up promised a revolutionary mechanic: a transformable fighter-mecha that could shift between a sleek spacecraft and a towering humanoid robot. While its premise evoked the epic mecha sagas of Gundam and Macross, Arrow Flash ultimately became a footnote in gaming history—admired for its ambition but criticized for its execution. Its legacy is one of unfulfilled potential: a game that dared to be different but couldn’t escape the shadow of contemporaries like Thunder Force III and Hellfire. This review dissects Arrow Flash‘s design, dissecting its innovations and flaws to reveal why it remains a curious, if flawed, artifact of the era.

Development History & Context

Arrow Flash emerged from the fertile ground of early 1990s Japanese game development, where ITL Co. Ltd.—a studio with limited prior pedigree—sought to capitalize on the Genesis’s burgeoning library of shooters. Producer Kenichi Hiza spearheaded the project, envisioning a game that blended the high-octane action of R-Type with the transforming mecha tropes popularized by anime. Technologically, the Genesis presented opportunities and constraints: its 16-bit hardware enabled vibrant sprites and layered scrolling, but also demanded careful optimization to avoid slowdown. The result is a game with competent but not spectacular visuals, occasionally hampered by performance issues during dense enemy encounters.

The 1990 shooter landscape was fiercely competitive. The Genesis was home to titans like Thunder Force II (1988) and the imminent Thunder Force III (1990), which raised the bar with their frantic pacing and inventive level design. Arrow Flash entered this arena not just as another shooter, but as an experiment. Its dual-form ship was a novel concept, echoing earlier transforming-vehicle games like Orguss (SG-1000) but expanding it into a full-fledged experience. Renovation Products marketed it in North America with generic sci-fi packaging, failing to highlight its unique hook. Despite Sega’s backing, the game never achieved blockbuster status, becoming a niche curiosity rather than a system-defining title.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Arrow Flash‘s narrative is a minimalist sci-fi epic, typical of the genre but enriched by deliberate tributes to mecha anime. Players assume the role of Zana Keene (Anna Schwinn in Europe, Starna Oval in Japan), a pilot inheriting her grandfather’s prototype fighter-mecha after his death at the hands of the alien “Great Golems.” The plot unfolds through brief, text-based cutscenes: Zana launches from a Macross-style carrier deck, battles through alien sectors, and confronts the dragon-like Overlord in the final stage. The narrative is a vehicle for spectacle rather than deep storytelling, but its thematic core resonates—legacy, vengeance, and humanity’s struggle against overwhelming odds.

The game’s lore is steeped in anime homages. The intro sequence mirrors Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam, with Zana resembling Kamille Bidan. Enemy designs evoke Gundam‘s Jegans, and the RMS-106 designation in the credits references the Hi-Zack mobile suit. These nods weren’t mere Easter eggs; they positioned Arrow Flash as a love letter to mecha fans. Yet, the dialogue is sparse and utilitarian, with no in-game voice acting or character development. Zana’s singular motivation—to save Earth—lacks nuance, but her portrayal as a female protagonist in a male-dominated genre was noteworthy. Ultimately, the narrative serves the gameplay, creating a cohesive if threadbare framework for its action.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Arrow Flash‘s gameplay revolves around its transformative core, executed with mixed results. The player controls Zana’s vessel, which can seamlessly switch between two forms: a swift fighter jet and a slower, more versatile mech. Each form dictates distinct playstyles:

– Fighter Jet: Emphasized speed and forward-focused firepower. It fires concentrated lasers, moves horizontally with agility, and trails “helper” ships in a snakelike pattern. Its Arrow Flash unleashes five screen-clearing blasts instantly.

– Mech: Prioritizes coverage and special utility. It fires wider shot angles (even backward with upgrades), gains faster vertical movement, and locks helper ships into fixed formations. Its Arrow Flash grants temporary invincibility, engulfing the mech in flames to damage enemies on contact.

Power-ups—scattered liberally but lost on death—include weapon upgrades (laser, arrow, wave patterns), Fire Claws (helper ships), Missile Ups (homing in mech mode), and Energy Shields (3-hit protection). The Arrow Flash itself operates under two modes: “Stock” for limited instant-use attacks or “Charge” for weaker, unlimited blasts requiring a wind-up.

However, the mechanics are riddled with flaws. The mech form, despite its theoretical advantages, feels sluggish and impractical. Majestic Lizard’s player review encapsulates this: “The ability to transform your ship from vehicle to mecha is essentially worthless.” The jet’s superior speed and firepower make it the default choice, rendering the mech a situational novelty at best. Combat is further undermined by questionable difficulty balancing. On normal settings, Arrow Flash is notably easy, especially when powered up. Enemy patterns are predictable, and bosses often feel uninspired—some recycled, others underwhelming. The final stage partially redeems this with its warship onslaught and cavern infiltration, but the preceding four levels are criticized for their monotony. As Sega Does lamented, “Arrow Flash is just way too easy,” undermining the tension that defines the genre.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Arrow Flash‘s visual direction leans into anime aesthetics, but its world-building remains surface-level. The game spans five stages (plus one vertical-scrolling segment), each set in distinct yet underdeveloped locales: a launch bay, asteroid fields, alien complexes, and a psychedelic “Great Worm Forest.” Backgrounds are sterile or abstract, failing to evoke a sense of place. Only the final stage—blending warship sieges with claustrophobic cave navigation—achieves genuine atmosphere. Enemy designs are imaginative, ranging from crystalline drones to serpentine dragons, but sprites are often small, reducing visual impact during chaotic battles.

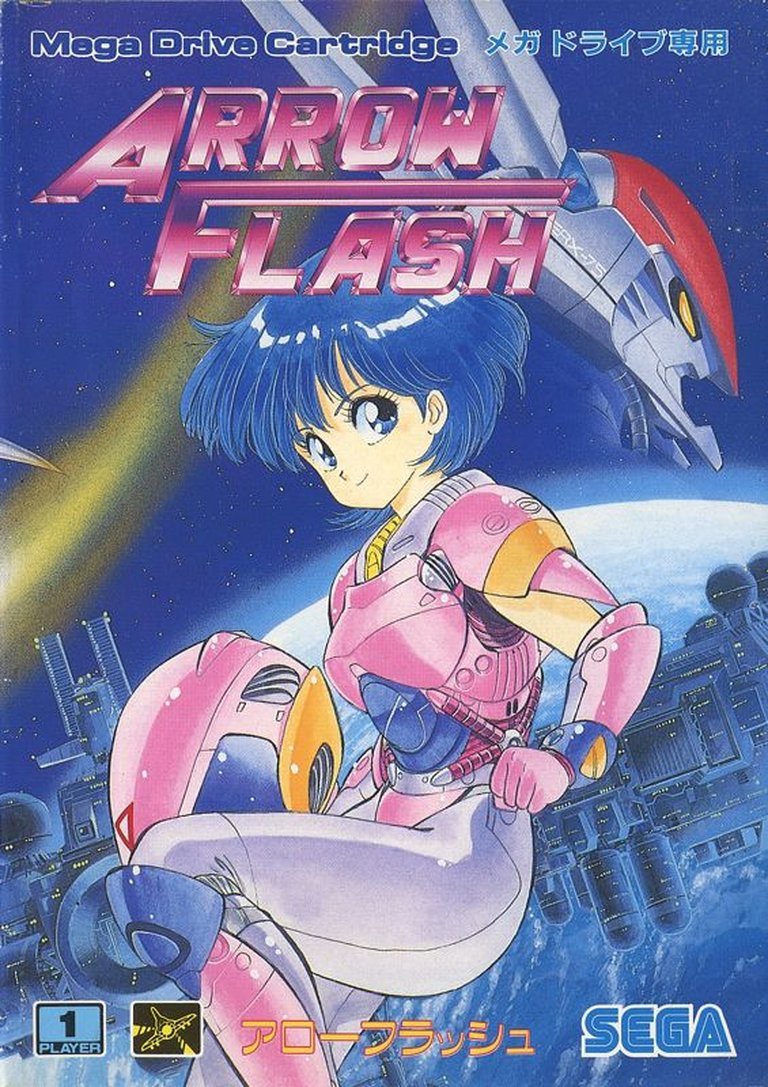

The art style is defined by “super deformed” (chibi) character designs, lending Zana and her helpers a cute, rounded appearance. This contrasts with the game’s mecha and boss designs, which are more detailed. Critics noted the limited color palette, with “blue, red, pink, and gray” dominating (Majestic Lizard). While technically competent for 1990, the graphics pale beside Thunder Force III‘s pyrotechnics. The Japanese cover art by Takashi Akaishizawa—featuring Zana in dynamic pose—outshines the in-game visuals, while the US cover by Frank Cirocco opted for a generic action scene.

Sound design is a standout. The soundtrack, composed by “Hanauri-musume” (per MobyGames), blends synth-driven melodies with rock influences. Tracks like the warship theme in Stage 5 are described as “rocking” and “cartonnent en cachette” (1UP! France). Sound effects are functional—laser zips and explosions are crisp but unremarkable. Yet, the audio fails to elevate the bland environments, creating a disconnect between the game’s aural excitement and its visual monotony.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Arrow Flash received a polarized reception, mirroring its design. Critical scores spanned from a scathing 16% (Sega Does) to a glowing 90% (Player One). French magazine 1UP! praised its “jouabilité affinée” and hidden musical depth, while Hobby Consolas lauded its “spectaculares gráficos.” Conversely, Sega Pro dismissed it as “irritating,” and Génération 4 awarded a brutal 3/10, citing its lack of challenge. Player reviews echoed this divide: Majestic Lizard called it a “decent shooter” for beginners, while Sega Does deemed it a “contender for worst Genesis shoot-em-up.” Commercially, it underperformed against genre titans, becoming a budget title over time.

In retrospect, Arrow Flash‘s legacy is defined by its ambition over execution. It pioneered a transformation mechanic later refined in titles like Android Assault (Sega CD), but its own implementation remains flawed. The game is now a cult curiosity, remembered for its female protagonist and anime influences. Its MobyGames score of 6.3 (#21,637 of 27K) reflects its middling status, while fan communities debate its merits. Some, like HowLongToBeat reviewer GoHoboGo, call it “underrated,” praising its “beautiful visuals.” Others, as Reddit threads conclude, see it as a “misfire”—a game with great ideas squandered by poor balance. It endures not as a classic, but as a cautionary tale: innovation without polish yields mediocrity.

Conclusion

Arrow Flash stands as a fascinating paradox: a shooter brimming with potential yet crippled by compromise. Its transforming ship-mech was a visionary concept that predated trends in the genre, but its execution was marred by imbalanced mechanics, undue ease, and underwhelming visuals. The narrative and art, while charming, lacked depth to anchor the experience. In the pantheon of Genesis shooters, it occupies a liminal space—not a masterpiece like Thunder Force III, nor a disaster like Super Real Darwin, but a “decent” (Majestic Lizard) yet forgettable entry.

For modern players, Arrow Flash offers niche appeal: its accessibility makes it a gentle introduction to shoot-’em-ups, and its anime flair resonates with fans of the genre’s roots. Yet, its flaws are undeniable. The mech form is a gimmick, the stages are repetitive, and the challenge evaporates with power-ups. As a historical artifact, it documents a bold experiment—one that, for all its flaws, underscores the creative risks of early 90s game development. Arrow Flash is, ultimately, a curio: a game that dared to be different, even if it couldn’t quite pull it off.