- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Daiso Sangyo Inc.

- Developer: TyoMaho Denno

- Genre: Action, Scrolling shoot ’em up

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Micromanagement, Powerup system, Score attack, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version is a challenging score attack-based overhead space shooter released in 2003 for Windows. Players navigate through waves of enemies in a sci-fi setting, balancing survival with maximizing points through a complex powerup system. The game features seven levels of primary shot power that can be switched on the fly, with higher levels offering increased firepower but draining the special shot meter faster. This meter powers the player’s bomb, which both destroys enemy bullets and fires homing shots against tougher enemies. The CD-ROM version represents an enhanced edition of the original freeware game, offering remixed, more challenging gameplay and recolored artwork that tests players’ reflexes and strategic decision-making.

TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version Patches & Updates

TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version Reviews & Reception

tasvideos.org : Techno Sylph is a very, very obscure freeware shoot em up that’s surprisingly great.

TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version: A Forgotten Masterpiece of Vertical Shoot ‘Em Up Sophistication

Introduction

In the pantheon of vertical scrolling shooters, TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version (2003) stands as a cult masterpiece—a niche Japanese gem that blended freeware roots with commercial refinement. Originally conceived as TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden (2002) by indie studio TyoMaho Denno, this CD-ROM reimagining represents a rare convergence of technical audacity, mechanical depth, and artistic restraint. Yet, despite its brilliance, it remains buried beneath the shadows of genre titans like Gradius and Touhou. This review argues that TechnoSylph is not merely a score-attack curiosity but a pioneering work of systemic design that redefined resource management in shooters, offering a blueprint for complexity that would later influence indie darlings like Xevious Resurrection. Its legacy lies in proving that innovation could thrive outside AAA pipelines, using the genre’s constraints as a canvas for elegant, punishing brilliance.

Development History & Context

Origins and Vision

TechnoSylph emerged from the fertile ground of early-2000s Japanese freeware development. Creator KBZ’s vision was explicit: to craft a “score attack-based overhead space shooter” where survival hinged not just on reflexes, but on strategic micromanagement. The freeware vsys gaiden (2002) served as a proof-of-concept, showcasing KBZ’s ambition to dismantle the genre’s traditional power-up tropes. The core innovation—a seven-tiered shot system balanced by a shared energy resource—was born from KBZ’s frustration with the “one-size-fits-all” upgrades prevalent in shooters of the era. This system demanded players constantly trade offensive power for defensive utility, creating a dynamic tension unseen in contemporaries like R-Type.

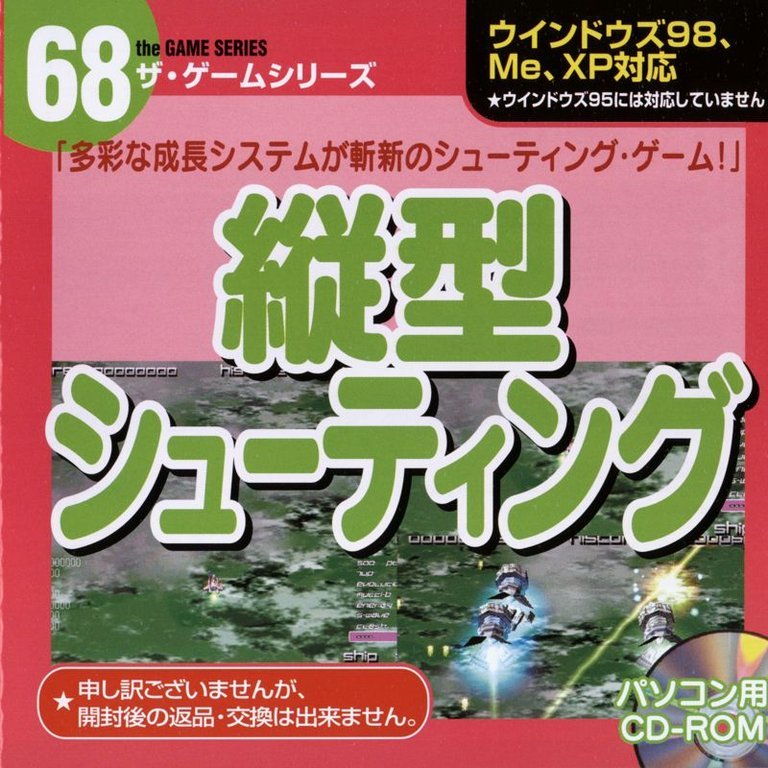

Technological Constraints and Commercial Evolution

Released in 2003 as volume 68 of Daiso Sangyo Inc.’s budget The Game Series, Special version operated within the constraints of mid-2000s Windows shareware. TyoMaho Denno’s team—comprising KBZ, Takatsuki Gumina, Toshimichi Saeki, Yūki Osabishi, and KEIY—worked with limited resources, rendering sprites in 2D with minimal animation. The game’s technical backbone was rudimentary: MIDI soundtracks, pixelated backgrounds, and a UI that displayed only critical numerical data. Yet these limitations became strengths. The stark visuals forced players to focus on the game’s intricate mechanics, while the CD-ROM format allowed for “remixed, more challenging gameplay” and recolored artwork—a response to community feedback on the freeware version. This iterative process reflected the studio’s commitment to player-driven refinement, a hallmark of indie development before the term was mainstream.

Gaming Landscape Context

TechnoSylph arrived during a transitional period for the shoot ’em up genre. While arcades declined in Japan, PC shooters like DoDonPachi and Mamehou dominated the hardcore scene. Yet TechnoSylph deliberately eschewed arcade bombast for cerebral depth. In contrast to the flashy bullet-hell games gaining traction, its monochromatic color palette and sparse aesthetics positioned it as an “anti-bullet hell”—a game where danger arose not from chaotic patterns, but from the player’s own choices. Its release as a budget title also aligned with the era’s experimental CD-ROM compilations, where Daiso Sangyo marketed niche games as “artistic experiments” rather than commercial products.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Absence of Story and Character

TechnoSylph is a world without words. There are no named characters, cutscenes, or dialogue—only cold, mechanical progression. The player’s ship evolves from the humble “Puppy” to the mighty “Genesis,” yet this transformation is purely functional, devoid of personality or backstory. Enemy designs evoke sci-fi archetypes (drones, reactors, bosses), but they exist as obstacles, not agents. This intentional narrative vacuum forces the player to project meaning onto the experience, framing the game as a metaphor for resource scarcity or technological evolution. The lack of lore is not a flaw but a design philosophy: it focuses the player entirely on the systemic dance of survival.

Thematic Resonance: The Tyranny of Choice

The game’s true narrative emerges from its mechanics. Every power-up selection, shot-level adjustment, and bomb usage tells a story of calculated risk. The seven-tiered shot system embodies the theme of costly empowerment: higher levels of firepower drain the energy needed for survival, forcing players to ask, Is this enemy worth my life? Similarly, the “Evolution” upgrade—where ships transform into new forms at the cost of upgrade slots—explores themes of obsolescence and renewal. Each evolution resets progress but offers new tools, mirroring real-world cycles of innovation. Even the score-attack focus reinforces a theme of futility: points accumulate, but death is inevitable, turning gameplay into a meditation on impermanence. In a genre often preoccupied with heroism, TechnoSylph presents a universe defined by relentless, impersonal systems.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Core Triad: Shot, Energy, and Bomb

At heart, TechnoSylph is a trinity of interdependent systems:

1. Shot Levels (1–8): The player’s primary weapon fires volleys of bolts with unique patterns and energy costs. Level 2 fires two bolts every 9 frames with minimal energy drain, making it ideal for farming points. Levels 5–8 fire rapidly but consume energy faster than it can recharge, forcing players to switch down to Level 2 mid-fight. This creates a rhythmic “dance” of power adjustment.

2. Energy Bar: A shared resource for both shot strength and bombs. Higher shot levels slow recharge, while bombs consume it in full blocks. Collecting “MAX” drops from reactors or robots increases the bar’s capacity, but upgrades reduce it—a cruel trade-off.

3. Bomb System: Bombs clear bullets and fire homing shots, but their utility extends beyond defense. By timing bomb use when the energy bar aligns with the “upgrade bar,” players can unlock permanent upgrades like “Evolution” or score multipliers. This transforms the bomb into a dual-purpose tool: survival and progression.

Ship Evolution and Upgrade Slots

The game’s progression revolves around “upgrade slots.” Each ship (Puppy → Sylph → Genesis) offers eight unique upgrades, such as “Multi-A” (follower drones) or “20,000 Points.” To acquire these, players must:

– Select an upgrade type (shown in the UI).

– Fill the upgrade bar by destroying enemies.

– Use a bomb when the energy bar reaches the upgrade bar’s height.

Each upgrade consumes one “MAX” block of energy permanently, making later runs riskier. The “Evolution” upgrade, when filled, allows ship changes—e.g., Puppy to Sylph. At the final tier, players can “evolution loop” by evolving into the same ship, resetting all upgrades to gain more point slots. This creates a high-stakes meta-game where players must decide whether to evolve or chase temporary score boosts.

AI and Enemy Design

Enemies follow predictable but punishing patterns. Drones swarm in formations, while bosses require precise shot-level adjustments. The “homing” shots from bombs are crucial for destroying armored enemies, adding a layer of tactical depth. The game’s difficulty curve is steep, with later stages demanding mastery of shot-switching and bomb timing—a stark contrast to the freeware version’s more forgiving approach.

UI and Presentation

The minimalist UI is a masterclass in information density. Three bars dominate the screen: shot strength (blue), energy (orange/yellow), and upgrades (pink). Ship sprites are small but detailed, with subtle palette swaps in Special version to enhance visibility. Controls are direct—arrow keys for movement, one for shots, one for bombs—leaving no room for error. This austere design ensures players focus on mechanics, not aesthetics.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Aesthetics

TechnoSylph’s art is functional yet evocative. The sci-fi setting is conveyed through abstract shapes: geometric enemies, monochromatic backgrounds, and minimalist structures. The recolored artwork in Special version (compared to the freeware) adds vibrancy without clutter—reds and blues pop against dark voids, creating visual landmarks for navigation. Ship designs evolve from the angular “Puppy” to the sleek “Genesis,” reflecting technological advancement. Bullet patterns are distinct: blue for standard shots, white for bombs, allowing players to identify threats at a glance. This clarity is vital in a game where split-second decisions determine survival.

Sound Design

The soundtrack, composed by Takatsuki Gumina and Toshimichi Saeki, is a blend of melancholic electronica and driving techno. MIDI tracks evoke the isolation of space, with pulsing beats underscored by melodic synth lines. Sound effects are equally purposeful: shot impacts are sharp, bomb explosions are booming, and enemy deaths trigger brief, satisfying chimes. This audio-visual synergy reinforces the game’s tension: calm melodies during lulls erupt into chaotic noise during boss fights. The absence of voice acting reinforces the game’s cold, impersonal universe, where only the player’s actions matter.

Atmosphere and World-Building

The game’s world is built through implication. Reactors and debris fields suggest a post-apocalyptic space, while enemy “robot” designs hint at a fallen empire. The lack of narrative allows players to imagine a universe where humanity’s legacy is reduced to battling machines for points. This minimalist world-building focuses the experience on the core loop: survive, upgrade, evolve.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception

Upon release, TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version received minimal attention. As a budget title in Daiso Sangyo’s The Game Series, it was overshadowed by mainstream releases. Niche communities like the TASVideos forum praised its mechanics, with one user calling it “a very, very obscure freeware shoot em up that’s surprisingly great.” However, critical reviews were scarce, with only one retrospective (from Old-Games.com) noting its “fun and very pretty” visuals while lamentating sluggish performance on slower PCs. Commercial data is absent, but its collector status—only two players have it on MobyGames—suggests limited distribution.

Evolution of Reputation

Over time, TechnoSylph gained cult status among hardcore shooter enthusiasts. The TASVideos forum detailed its intricate routing for maximum score, revealing depths unseen in casual play. Its freeware predecessor became a staple of Japanese doujin communities, where players lauded KBZ’s “unique level-up ship progression.” Today, it’s remembered for its complexity, even as accessibility remains a barrier. Modern retrospectives (e.g., SocksCap64) highlight its “complex powerup system” as a precursor to games like Cave Story, where mechanics drive narrative.

Influence and Legacy

TechnoSylph’s legacy lies in its systemic innovation. The energy-shot-bomb triad foreshadowed resource-management systems in indie games like Hellsinker and Xevious Resurrection. The “evolution loop” mechanic also anticipated the replay-focused design of modern rougelites. While it never influenced AAA titles, its freeware roots exemplify the DIY ethos that defined early 2000s indie gaming. KBZ’s work remains a blueprint for creating depth within genre constraints—a lesson that resonates in an era of bloated game design.

Conclusion

TechnoSylph: vsys gaiden Special version is more than a forgotten shooter; it’s a testament to the power of minimalist design. In a genre often criticized for repetition, KBZ and TyoMaho Denno crafted a universe where every choice—from shot level to bomb timing—carries existential weight. Its austere aesthetics and punishing systems may alienate newcomers, but for those who master its dance of energy and evolution, it offers transcendent satisfaction. As a historical artifact, it bridges the gap between arcades and indie gaming, proving that innovation could thrive in the cracks of commercialism. Though its legacy is niche, TechnoSylph’s influence is undeniable: it redefined what a vertical shooter could be, one pixel at a time. For historians and gamers alike, it stands not as a relic, but as a masterpiece of calculated brilliance.