- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Rhinosoft Interactive, ValuSoft, Inc.

- Developer: Eternal Warriors LLC

- Genre: Action, Educational

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 41/100

Description

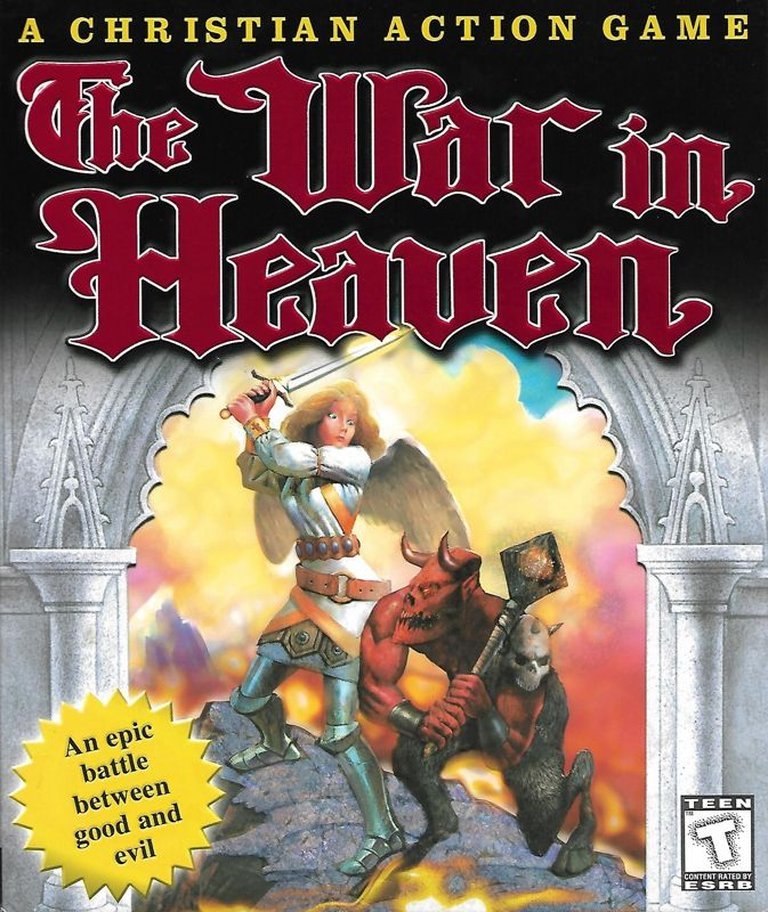

The War in Heaven is a Christian-themed first-person action shooter set in a pseudomedieval fantasy world, based on Theodore Beale’s novel series, where players battle hissing horned monsters and Bible-named characters wielding swords and weapons across limited levels. Players choose between the Divine Path of Obedience to ascend 12 levels to Heaven as an angel or the Fallen Path of Power to follow Lucifer, become a demon, and war against angels.

Gameplay Videos

The War in Heaven Cracks & Fixes

The War in Heaven Patches & Updates

The War in Heaven Mods

The War in Heaven Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (20/100): there’s more activity in Sunday school than in this game

myabandonware.com (73/100): Not a great game, but admittingly an interesting one.

somethingawful.com : you just wasted a good 10 bucks on this game that you could’ve spent on chocolate-flavored toothpaste.

The War in Heaven: Review

Introduction

In the late 1990s, as first-person shooters like Quake II and Unreal redefined gaming with their technical wizardry and visceral intensity, a curious outlier emerged from the fringes: The War in Heaven, a Christian-themed action game that pitted players against horned demons and celestial angels in a pseudomedieval fantasy realm. Dubbed “Doom-meets-the-Bible” by contemporaries, this 1999 Windows title from Eternal Warriors LLC dared to infuse the blood-soaked corridors of FPS gameplay with spiritual warfare, biblical nomenclature, and a stark moral dichotomy. Developed amid a burgeoning market for faith-based entertainment, it promised players a choice between divine ascension or demonic rebellion—yet delivered a product hamstrung by amateurish execution. This review argues that The War in Heaven endures not as a gaming triumph, but as a fascinating artifact of cultural ambition: a earnest, if inept, bid to evangelize through pixels, whose flaws illuminate the chasm between pious intent and technical reality.

Development History & Context

The War in Heaven was born from Eternal Warriors LLC, a small studio founded in 1996 by a tight-knit team led by designer Theodore Beale (aka Vox Day), whose Christian fantasy novel series of the same name provided the foundation. Beale, credited for both design and narrative, drew inspiration from Dr. S. Gregory Boyd’s sermons on spiritual warfare—a nod immortalized in the credits alongside special thanks to “Jesus Christ (our Lord Savior Jesus Christ of Nazareth)” and the Shoreview Bible Study group. Producer Andrew Lunstad oversaw a modest crew: programmers Benton Jackson, Eric Dybsand, and Jon Nelson handled the custom “in-house” engine, while artists like Rocco Basile and Emil Busse crafted visuals, and Michael Larson composed audio using the Miles Sound System.

Released in October 1999 via budget publisher ValuSoft (a GT Interactive subsidiary known for low-cost fare like Deer Hunter clones), the game arrived during the FPS golden age. Half-Life had just revolutionized storytelling in shooters, and hardware leaps via 3D accelerators like the Voodoo2 card set sky-high expectations. Yet The War in Heaven was constrained by its indie ethos and religious focus: built for Windows 95/98 with Direct3D 5 support, it targeted Pentium-era rigs with just 16MB RAM and 120MB storage. ESRB-rated Teen for violence (toned down to avoid gore), it aimed at Christian males 15+, filling a niche underserved amid rising concerns over games’ moral decay. ValuSoft’s bargain-bin distribution reflected its modest scope—straightforward CD-ROM affair with keyboard/mouse controls—but technological shortcuts (e.g., stiff animations, laggy door transitions) betrayed a team punching above its weight, prioritizing message over polish in an era demanding both.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, The War in Heaven adapts Beale’s novels into an interactive allegory of cosmic conflict, transplanting biblical figures—Lucifer, Gabriel, Michael—into a pseudomedieval tapestry of sword-wielding horrors. Players select from two archetypal paths: the Divine Path of Obedience, ascending 12 levels as an angel toward Heaven’s gates, or the Fallen Path of Power, descending as a demon under Lucifer to assail celestial hosts. This binary choice frames the plot as a morality play on free will, obedience, and rebellion, echoing Revelation’s War in Heaven while emphasizing “spiritual warfare”—demons hiss temptations, angels intone scripture, and levels pulse with tasks like reclaiming relics, destroying shrines, or converting foes (demons-only).

Characters are archetypal vessels for theology: biblical names lend authenticity, but dialogue veers from solemn (“The peace that surpasses understanding awaits the obedient”) to heavy-handed preachiness, interspersed with Bible verses. Voice acting—by Lunstad, the Pedrottys, and Mary Stahl—is earnest but amateur, with angelic tones lofty and demonic sneers cartoonish. Themes probe eternal consequences: Divine runs stress sacrifice and faith, Fallen ones power’s seductive corruption, culminating in Heaven’s ascent or infernal dominance. Yet the narrative falters in delivery—linear progression and sparse cutscenes reduce nuance, turning profound motifs into repetitive sermons. Easter eggs (e.g., Jesus battling God amid angelic assaults) hint at subversive whimsy, but overall, it’s a didactic fever dream: bold in evangelizing FPS tropes, yet undermined by simplistic plotting that prioritizes conversion over cohesion.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Fundamentally a first-person shooter with melee emphasis, The War in Heaven loops around corridor-crawling combat against hissing, horned monsters brandishing swords and axes. Core mechanics are direct: WASD/mouse for sluggish movement (famously the “slowest hero ever”), mouse1 for attacks, with a sparse arsenal—blessed swords, spears, demonic implements—unlocked via progression. No guns; violence is visceral yet restrained (no gore), focusing on timing swings, dodging, and parrying in tight arenas. Paths diverge subtly: angels reclaim holy ground, demons corrupt or destroy, with six missions each (12 total levels) blending shooting, light exploration, and objectives like armor hunts.

Progression is rudimentary—no skill trees, just incremental power-ups tied to alignment. UI is minimalist: health/weapon bars dominate a clean HUD, but lacks stamina or combo feedback, amplifying repetition. Flaws abound: buggy hit detection, clipping animations, glacial pacing (12-second door loads), and outdated engine (textures akin to 1995 tech) breed frustration. Patches (e.g., v1.0) and fixes (Preferences.ini tweaks for resolution/FOV) mitigate some, but core loops feel unpolished—replayability stems from dual paths, yet limited variety caps sessions. Innovative? The moral choice system prefigures alignment mechanics in later RPG-shooters like F.E.A.R., but execution is flawed: serviceable for nostalgia, unforgivable for contemporaries expecting Quake‘s fluidity.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s pseudomedieval fantasy setting—swirling mist battlegrounds, ruined cathedrals, abyssal pits, heavenly spires—evokes a stark Heaven/Hell duality, with architecture praised nostalgically for uniqueness (e.g., intricate stonework amid era peers). Visuals employ earthy tones, stained-glass glows, and particle auras (divine sparkles, demonic embers), but low-res textures, repetitive tiles, and stiff models betray budget limits—enemies clip through geometry, shadows dramatic yet inconsistent. Lighting shines in cathedrals, reinforcing ethereal mood, though 1999 hardware strains yield pop-in and aliasing.

Sound design leverages Miles for ambient menace: hissing foes, clanging steel, choral hymns for angels, guttural snarls for demons. Michael Larson’s score mixes orchestral swells with electronic undertones (Juno 106 filters noted), but voice work is tinny, and SFX loops grate. No surround, basic sliders for SFX/CD. Collectively, these forge an unsettling atmosphere—monotonous tones and scripture evoke creeping dread, alienating secular players while immersing faithful ones. It’s cohesive world-building on a shoestring: atmospheric for spiritual warfare, but technically creaky, amplifying thematic isolation.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was dismal: MobyGames critics averaged 30% (Game Vortex 50%: “applauds intent but lost in high expectations”; Absolute Games 20%: scathing Russian dismissal; All Game Guide 1/5: “horrible… throw into a fire”). Washington Post‘s Mike Musgrove quipped, “more activity in Sunday school.” Players averaged 2.5/5, with abandonware forums split—nostalgics cherish memories (“countless hours… fond despite bad”), others decry bugs (“bargain bin for a reason”). Sales limped to 4,000 by March 2000, 10,000 by October—modest for ValuSoft.

Legacy is niche: a punchline in Something Awful’s savage roast (“throw rocks at Satanic toads”), it influenced scant successors, though dual-path spiritual FPS echoes in Heaven and Hell: The Last War. As Christian gaming pioneer (pre-Left Behind: Eternal Forces), it highlights genre evangelism’s pitfalls amid 90s moral panics. Cult status persists via abandonware (MyAbandonware 3.67/5 from votes), with calls for remakes underscoring untapped potential. No industry shaker, but a historian’s curiosity: emblematic of faith clashing with commerce.

Conclusion

The War in Heaven is a noble failure—a pious FPS fever dream whose heartfelt theology crashes against amateur tech, yielding sluggish combat, dated visuals, and preachy narrative in a 12-level morality gauntlet. Its dual paths and biblical flair innovate modestly, but bugs, repetition, and low polish relegate it to obscurity. In video game history, it claims a footnote as Christian gaming’s awkward adolescence: ambitious evangelism amid FPS excess, beloved by nostalgics, mocked by critics. Verdict: 3/10—play for curiosity, not quality; a relic reminding us that even Heaven’s war demands more than good intentions.