- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Leaf Sverige AB

- Developer: Int:act Media & Communication

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Single-player

- Average Score: 68/100

Description

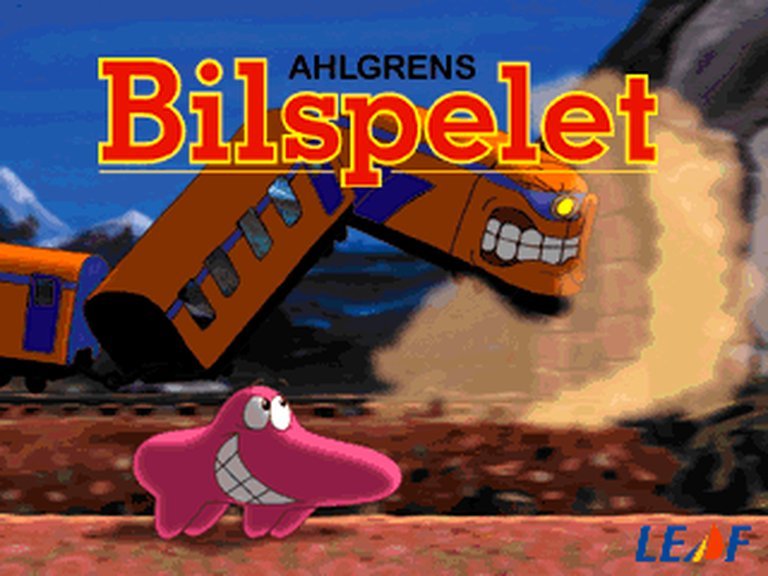

Ahlgrens Bilspelet is a 1997 top-down racing game featuring cartoonish cars modeled after Ahlgrens, classic Swedish sweets, in a championship across four cyclical tracks where players race multiple laps against three opponents while staying on the road to earn points based on finishing position, supporting both single-player against AI and IPX LAN multiplayer.

Ahlgrens Bilspelet: Review

Introduction

Imagine hurtling around looping tracks in cars modeled after chewy Swedish sweets—Ahlgrens bilar, those iconic gummy treats shaped like colorful automobiles. In 1997, amid the pixelated chaos of early Windows gaming, Ahlgrens Bilspelet emerged as a whimsical advergame that blended candy branding with top-down racing simplicity. Developed by the obscure Swedish studio Int:act Media & Communication and published by Leaf Sverige AB, this title stands as a forgotten footnote in gaming history, a promotional relic distributed likely via floppy disks in Sweden. Its legacy? A testament to how brands co-opted the nascent PC gaming boom for lighthearted marketing. My thesis: While mechanically rudimentary and narratively barren, Ahlgrens Bilspelet endures as a charming artifact of 1990s advergames, encapsulating the era’s technological innocence and the playful fusion of consumerism with digital entertainment.

Development History & Context

Ahlgrens Bilspelet was crafted by a lean team of seven at Int:act Media & Communication, a small Swedish developer whose portfolio remains elusive beyond this project. Key credits include Mats Henricson on game programming—his sole listed title, suggesting a one-off venture—and tools programming by Niklas Derouche. Graphics and design fell to Andreas Lanjerud (credited on 17-18 other games) and Jim Studt (three other titles), with Filmtecknarna handling interstitial pictures and Henrik Liljekvist providing technical assistance. Produced entirely in-house by Int:act, it reflects the boutique, low-budget ethos of late-90s European indie development.

Released in 1997 exclusively for Windows in Sweden, the game arrived during a transitional era for PC gaming. Windows 95 had democratized access, but hardware varied wildly—think Pentium processors, 16MB RAM, and DirectX’s infancy. Technological constraints are evident: a top-down racer clocking in at just 2MB on floppy, optimized for low-spec machines without 3D acceleration. The gaming landscape? Domination by 3D pioneers like Quake and Tomb Raider, yet 2D racers like Micro Machines and Super Mario Kart (via emulation) thrived on simplicity. As a licensed advergame tied to Ahlgrens sweets—a classic Swedish confectionery since 1953—the title exemplifies product tie-ins proliferating in Europe. Publishers like Leaf Sverige AB specialized in such promotional fare, capitalizing on local brands amid a console-PC divide. No patches or expansions noted; it shipped complete, a snapshot of IPX-era LAN culture before broadband.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

In a genre prioritizing velocity over verbosity, Ahlgrens Bilspelet dispenses with traditional storytelling, opting for a skeletal championship structure. There’s no plot beyond a four-race tournament featuring “ahlgrens cars”—anthropomorphic vehicles modeled after the sweets’ blue, yellow, red, and green hues. Players select one of four candy racers, embodying a silent protagonist in a saccharine showdown. No cutscenes, voiced dialogue, or character arcs; interstitial pictures by Filmtecknarna (likely static candy-themed artwork) serve as menu transitions, reinforcing the branding.

Thematically, it’s pure promotion: competition as confectionery joyride. Tracks evoke looping candy lands—cyclical circuits demanding precision to avoid “moving out the road,” symbolizing the sticky peril of veering from the brand’s sweet path. Underlying motifs include consumerism’s gamification; points accrue per placement (first: max points, etc.), culminating in a championship win that implicitly endorses Ahlgrens as the ultimate treat. No deeper lore—no rivalries, backstories, or satire—but this minimalism amplifies its charm. In an era of epic RPGs, it subverts expectations, whispering, “Gaming isn’t just dragons; it’s also gummy cars.” Critically, the absence of narrative flaws immersion for solo play, yet enhances multiplayer’s chaotic camaraderie. Ahlgrens as “characters” personify Swedish nostalgia, turning passive snacking into active rivalry—a clever thematic hook for its audience of kids and candy loyalists.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Ahlgrens Bilspelet loops a straightforward racing formula: select car, race laps on cyclical tracks, score points by placement. Four tracks demand multi-lap endurance, with victory hinging on staying on-road amid AI or human opponents. Controls—arrow keys for steer/accelerate, likely spacebar brake—are forgiving yet punishing; straying off-track slows you, enforcing track mastery without power-ups or weapons.

Core Loop Deconstruction:

– Single-Player: Vs. three AI cars. Opponents exhibit basic pathing—predictable laps with mild aggression—making wins accessible yet replayable via points chase.

– Multiplayer: Up to four players via IPX LAN, a 1997 staple pre-Internet dominance. Same-game sessions foster local network parties, though setup (IPX compatibility) gated accessibility.

– Progression: Championship mode tallies points across races; no upgrades, levels, or unlocks. Pure skill-based escalation.

Innovations? Top-down cartoon physics emphasize drift-free precision on loops, akin to TrackMania precursors. Flaws abound: no collision damage (bumps glance off), rudimentary AI (no overtakes?), and absent UI polish—no lap counters visible in descriptions, minimal HUD. No save system; floppy-era brevity (quick sessions). Balance tilts promotional—player car feels nimble, subtly biasing brand love. Overall, it’s Micro Machines lite: addictive in bursts, flawed by repetition, redeemed by multiplayer mayhem.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” is a minimalist candy utopia: four cyclical tracks rendered in vibrant, cartoonish 2D sprites. Ahlgrens cars bounce with squash-and-stretch animation, their gummy forms exaggerated—oversized wheels, candy wrappers as liveries. Environments? Abstract loops with roadside hazards (grass? barriers?), evoking sugary circuits without literal Ahlgrens factories. Atmosphere nails whimsy: bright palettes (primary colors dominate) contrast gritty 90s racers, immersing via nostalgia.

Visual direction—Lanjerud and Studt’s handiwork—prioritizes clarity over spectacle. Top-down view aids navigation, but low-res sprites (era-appropriate) lack detail; no parallax scrolling or effects noted. Interstitial art bridges races, likely Ahlgrens billboards or podiums, reinforcing branding.

Sound design? Un-documented, implying chiptune simplicity: looping upbeat synth tracks (Swedish pop flair?), basic engine whirs, crash beeps. No voiceovers; effects underscore cartoon physics—boings for bounces, whooshes for speed. These elements coalesce into a cohesive, lighthearted vibe: visuals pop on CRTs, audio loops unobtrusively, crafting a “pick-up-and-race” joy that elevates its promo roots to playful escape.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception? Nonexistent in English press; Sweden-only release yielded no critic scores (Metacritic: TBD). MobyGames logs a dismal 1.8/5 from one player (no reviews), flagging it “unranked.” Abandonware sites like MyAbandonware rate 5/5 from two votes—nostalgia bias?—while Giant Bomb and others offer zilch. Commercially, success as promo: bundled with sweets? Distributed freely, prioritizing brand exposure over sales.

Reputation evolved minimally; added to MobyGames in 2006 by POMAH, last updated 2023. No retrospectives, videos, or forums buzz—obscurity defines it. Influence? Negligible on majors, but emblematic of advergames (Pepsiman, Cool Spot). Prefigures candy racers like Candy Crush Saga modes or Hot Wheels. Preserved on Retrolorean/MyAbandonware (2MB downloads), it symbolizes 90s ephemera: playable with tinkering (DOSBox?), a curio for historians tracing branded gaming’s roots in Nordic markets.

Conclusion

Ahlgrens Bilspelet distills 1997’s unpretentious joys: cartoon cars, LAN laughs, and sly marketing. Its sparse narrative, basic mechanics, and charming art falter under modern scrutiny—repetitive, unpolished—yet shine as historical purity. No revolutions, just a sweet sprint. Verdict: 3/10 for playability, but an essential niche treasure in video game history—a fizzy reminder that not all legends roar; some merely zoom with gummy glee. Seek it on abandonware for a taste of Swedish digital confectionery.