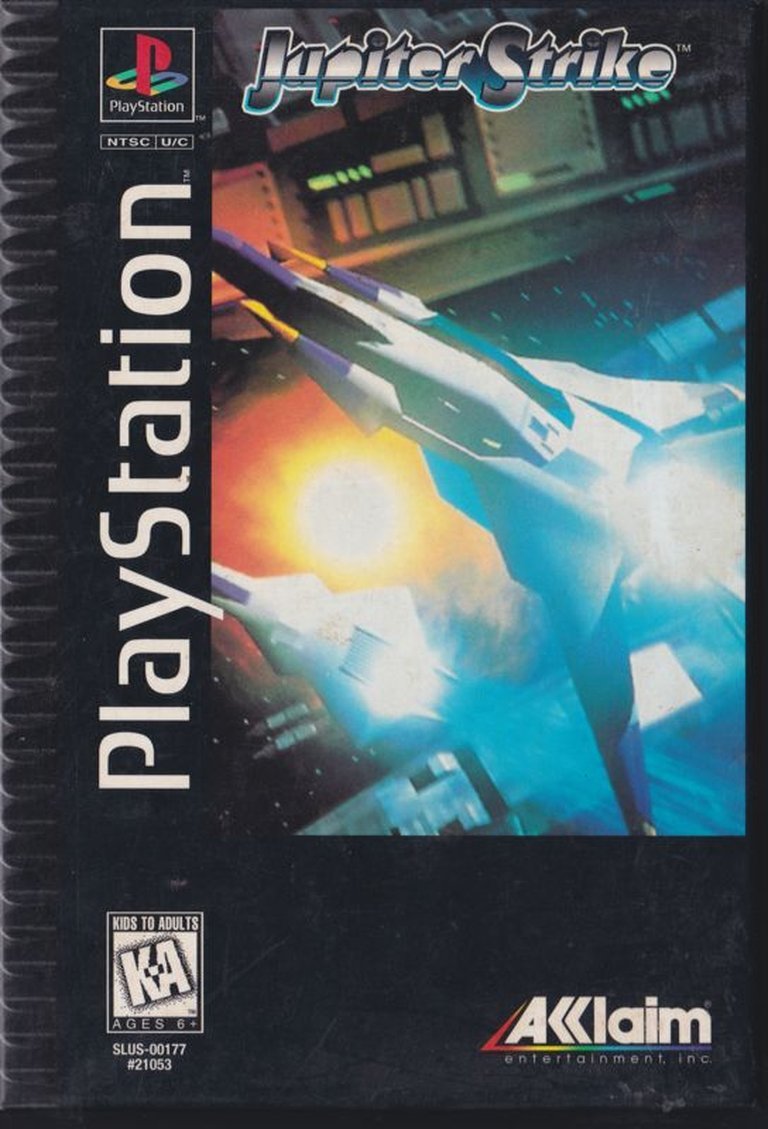

- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Acclaim Entertainment, Inc., GameBank Corp., GT Interactive Software Corp., Rainbow Arts Software GmbH, Taito Corporation

- Developer: Taito Corporation

- Genre: Action, Shooter

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Boss fights, On-rails, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 35/100

Description

Zeitgeist, also known as Jupiter Strike, is a mid-1990s sci-fi shooter where players pilot a futuristic fighter jet through space, battling waves of alien foes, asteroids, and colossal boss ships like motherships. With restricted movement mechanics, the game emphasizes precision targeting using twin main weapons and a homing laser sub-weapon—uniquely omitting traditional power-ups. Developed by Taito Corporation, it features missions across planets and space stations, framed by a retro 3D aesthetic typical of its 1995 PlayStation release era.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Zeitgeist

PC

Zeitgeist Mods

Zeitgeist Guides & Walkthroughs

Zeitgeist Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (20/100): Jupiter Strike is noteworthy strictly for having almost no good qualities at all.

collectionchamber.blogspot.com : It doesn’t impress in the gameplay department.

mobygames.com (51/100): The game only allows limited movement of the jet, prompting the player to focus on targeting and destroying as much as he can on his path.

Zeitgeist Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 1 (PS1)

Use a CodeBreaker device for hex codes. For button sequences: pause the game, hold Start for 10 seconds, then press L1/L2 while holding Start.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 800BB450 0062 | Unlimited Shield |

| 800BB894 0062 | Unlimited Shield |

| Hold Start for 10 seconds, then press L1 while holding Start | Top View |

| Hold Start for 10 seconds, then press L2 while holding Start | Side View |

Zeitgeist: A Flawed Odyssey Through Early 3D Space

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, the video game industry stood on the precipice of a technological revolution, with the PlayStation heralding a new era of 3D gaming. Amidst this seismic shift, Taito’s Zeitgeist (released in the West as Jupiter Strike) emerged as an ambitious yet deeply flawed space shooter that encapsulates both the promise and growing pains of early polygonal design. Directed by Masayuki Soh and executive produced by Tomohiro Nishikado—legendary creator of Space Invaders—the game sought to marry arcade sensibilities with the PlayStation’s nascent capabilities. Yet, despite its cinematic aspirations and sci-fi spectacle, Zeitgeist ultimately stumbled under the weight of cumbersome controls, repetitive design, and a glaring lack of innovation. This review examines how a game with Taito’s pedigree and technical ambition became a cautionary tale of style over substance, and why its legacy remains a footnote in the annals of rail-shooter history.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

Developed by Taito Corporation and released in Japan in August 1995 (and later localized by Acclaim Entertainment for Western audiences), Zeitgeist arrived during a critical juncture for 3D gaming. The PlayStation, only months old, was hungry for titles that showcased its graphical prowess. Taito, leveraging its arcade heritage, aimed to deliver a visceral space combat experience. The team, led by producer Eiji Takeshima, utilized texture mapping, Gouraud shading, and dynamic camera angles—features still novel in console gaming—to create a sense of depth and spectacle.

However, the game’s development was hamstrung by the era’s limitations. Polygon counts were modest by today’s standards, leading to simplistic enemy models, while the absence of analog stick support (the PlayStation’s DualShock controller debuted in 1997) forced players to navigate with the D-pad, resulting in clunky, imprecise movement. Taito’s decision to forgo power-ups—a staple of the shooter genre—further highlighted a misguided focus on minimalist design that alienated players accustomed to the strategic depth of contemporaries like StarFox or Panzer Dragoon.

The Gaming Landscape of 1995

Zeitgeist entered a market saturated with rail shooters and space operas. Nintendo’s StarFox (1993) had already set a high bar for on-rails action with its inventive lore and charismatic characters, while Rebel Assault II (1995) leaned heavily into FMV-driven storytelling. Against these titans, Zeitgeist struggled to distinguish itself. Its muted critical reception (averaging 51% across 10 reviews, per MobyGames) reflected a broader industry pivot toward games that balanced technical ambition with refined gameplay—a balance Zeitgeist failed to strike.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot and Characters

Zeitgeist’s narrative is archetypal sci-fi fare: Earth faces annihilation by an alien armada, and a lone pilot (the unnamed “hero”) must spearhead a counteroffensive dubbed “Jupiter Strike.” The story unfolds through brief FMV cutscenes—a novelty at the time—but these sequences, criticized by GameFan Magazine as “cheesy” and “grossly overdone,” offer little substance. Characters are nonexistent; the protagonist is a faceless entity, and adversaries lack the personality of StarFox’s Andross or Panzer Dragoon’s bio-mechanical horrors.

Themes and Tone

Thematically, Zeitgeist leans into dystopian militarism and human resilience, but its execution feels hollow. Unlike Gradius or R-Type, which wove environmental storytelling into their level design, Zeitgeist’s asteroid fields and space stations serve as interchangeable backdrops for mindless combat. The title itself—meaning “spirit of the times”—rings ironic, as the game’s lack of narrative ambition clashed with the era’s push toward immersive worlds (e.g., Final Fantasy VII’s cinematic storytelling, still two years away).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop

As a rail shooter, Zeitgeist follows a linear path through eight stages, tasking players with obliterating waves of enemies, dodging obstacles, and battling screen-filling bosses. The jet features two weapons: a standard forward-firing laser and a lock-on homing missile system. The latter requires players to manually target enemies (up to a limited number) before unleashing a volley—a mechanic praised by GamePro for its “absorbing combat” but lambasted elsewhere for its fiddly implementation.

Critical Flaws

- Controls and Collision Detection: The game’s most damning flaw lies in its controls. As IGN noted, collision detection is “useless,” with hitboxes often misaligned. The D-pad’s binary input made precise dodging impossible, while the choice between third-person and first-person views (the latter obstructed by the ship’s cockpit) exacerbated disorientation.

- Difficulty and Progression: With no power-ups, checkpoints, or difficulty settings, Zeitgeist devolves into a war of attrition. Mega Fun highlighted a notorious third-stage bottleneck where “even Luke Skywalker would eject,” encapsulating the game’s punitive design.

- Repetition: Enemy patterns grow predictable, and boss fights—while visually imposing—boil down to dull bullet-sponge encounters.

Innovation vs. Iteration

Taito’s sole innovation—the lock-on mechanic—foreshadowed systems later perfected in Star Fox 64 (1997). However, without upgrades or strategic variety, this feature felt undercooked. The absence of multiplayer or alternate paths further limited replayability.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Zeitgeist’s art direction oscillates between ambitious and anemic. Textured polygons lend depth to asteroid fields and neon-lit space stations (The Collection Chamber praised the “varied enemy designs”), but environments lack the cohesion and detail of Wipeout’s dystopian raceways. Pop-in is minimal—a technical feat for 1995—but enemy designs, per Video Games Germany, feel “uninspired,” borrowing heavily from StarFox without adding flair.

Sound Design

The soundtrack, composed by Shinichiroh Shinozaki, stands as the game’s lone triumph. Mega Fun called it “majestisch und sphärisch” (majestic and spherical), with orchestral swells elevating tense encounters. Sound effects, however, drew universal scorn. GameFan decried the “ear-shattering” explosions, while Game Zero mocked the “quality of the sound effects” as “nil.”

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception

Critics savaged Zeitgeist at release. IGN’s 2/10 review declared it “an example of how not to make a game,” while Game Players lamented its “stacked dynamics.” Positive notes were rare: GamePro (80%) applauded its “responsive controls,” and Hacker (73%) lauded the graphics, but these were outliers. Commercial performance mirrored this disinterest; the game faded quickly from shelves.

Long-Term Influence

Zeitgeist’s legacy is one of caution. It exemplified the pitfalls of prioritizing technical showmanship over playability—a lesson heeded by peers like Panzer Dragoon II (1996), which refined its predecessor’s formula with tighter controls and narrative depth. The game’s lock-on mechanic, however, subtly influenced later shooters, including Star Fox 64’s targeting system.

Conclusion

Zeitgeist is a relic of gaming’s awkward adolescence—a title bursting with technological ambition yet crippled by foundational design flaws. Its sleek visuals and stirring score hint at the immersive experiences the PlayStation would soon deliver, but its sloppy controls, repetitive gameplay, and lack of player agency render it a frustrating artifact rather than a timeless classic. For historians, Zeitgeist offers a poignant case study in the perils of transitional-era game design. For players, it remains a curious, if cautionary, footnote—a game that grasped for the stars but fell tragically short. Final Verdict: A visually ambitious yet mechanically broken shooter that epitomizes the growing pains of early 3D gaming.