- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Industrial Data Design Pty. Ltd.

- Developer: Industrial Data Design Pty. Ltd.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: 3D, Camera rotation, Marking, Minesweeper mechanics, Tile-based

Description

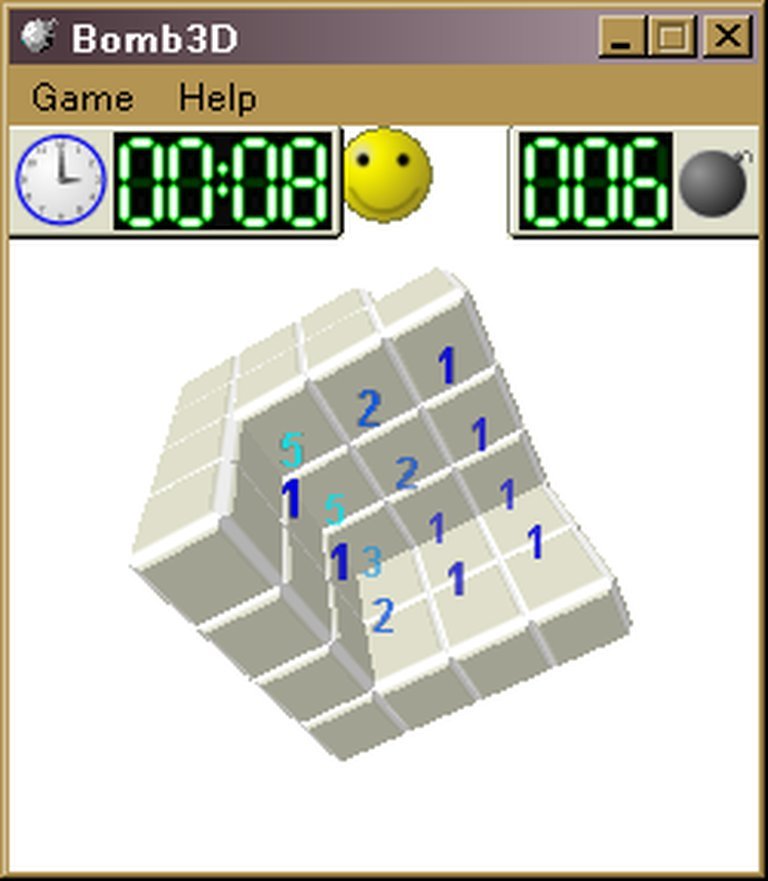

Bomb3D is a 3D variant of the classic Minesweeper game, featuring a cubical playfield instead of a flat board. The objective remains the same: identify and mark all bomb tiles without detonating any. Players can navigate a 3D camera around the playfield, with various board sizes and customizable skins available to enhance the gameplay experience.

Bomb3D: A Cubic Conundrum in the Shadow of Classics

Introduction

In the pantheon of puzzle games, Minesweeper reigns as a timeless titan—a deceptively simple grid of numbers and terror that consumed office workers and PC gamers for decades. Bomb3D, released in 2003 by the obscure Australian studio Industrial Data Design Pty. Ltd., dared to reimagine this classic in three dimensions. While its ambition to modernize a beloved formula was commendable, Bomb3D remains a curious footnote in gaming history: a technical experiment that never escaped the gravitational pull of its predecessors. This review dissects its innovations, shortcomings, and fleeting legacy in an era dominated by blockbuster franchises.

Development History & Context

The Studio & Vision

Industrial Data Design Pty. Ltd. left almost no mark on the industry beyond Bomb3D. The studio’s sparse credits and lack of online presence suggest a small, possibly amateur team capitalizing on the early 2000s shareware boom. Their goal was straightforward: adapt Minesweeper’s logic-based gameplay into a 3D space, leveraging the growing accessibility of 3D rendering tools for Windows PCs.

Technological Constraints

2003 was a transitional year for PC gaming. While AAA titles like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic pushed graphical boundaries, smaller studios like Industrial Data Design worked with有限的 resources. Bomb3D’s rudimentary 3D engine prioritized functionality over flair, relying on basic cube-based geometry and texture swaps. The lack of particle effects or dynamic lighting—common even in indie games of the time—underscored its budget constraints.

The Gaming Landscape

Bomb3D launched into a market saturated with puzzle games, from Tetris clones to experimental indie projects. Its September 2003 release coincided with heavy hitters like Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Call of Duty, ensuring it would drown in obscurity. Shareware distribution offered little visibility, and without marketing, it became a drop in the ocean of digital curiosities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a pure puzzle game, Bomb3D lacks narrative or thematic depth. There are no characters, dialogue, or lore—only the cold, clinical pursuit of logic. Its “story” is the player’s solitary battle against probability, a tension mirrored in the original Minesweeper. The absence of context or progression systems feels stark by modern standards, reflecting a design philosophy rooted in simplicity rather than immersion.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop

The premise is identical to Minesweeper: identify hidden bombs using numeric clues. The twist lies in the 3D cubical grid, where each cube segment can be adjacent to up to 26 neighbors (including diagonals). This exponential complexity transforms the puzzle into a spatial nightmare. Left-clicking reveals empty cubes with bomb counts, while right-clicking marks suspected bombs with an “X” or “?” for uncertainty.

Innovations & Flaws

- Camera Freedom: The ability to rotate and zoom the playfield was Bomb3D’s standout feature, allowing players to inspect angles—though clunky controls often hindered precision.

- Customization: Players could adjust grid sizes or apply cosmetic “skins,” a novelty for the era. However, these skins were purely aesthetic, offering no gameplay variation.

- Accessibility Issues: The shift to 3D introduced visual clutter. Counting bombs across layers became laborious, and the lack of a “chording” mechanic (quick-clearing adjacent tiles) slowed pacing.

UI & Progression

The point-and-select interface functioned adequately but felt archaic compared to contemporaries like Lumines. No scoring system, time trials, or difficulty tiers existed to incentivize mastery. Bomb3D was a sandbox, not a challenge.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

The game’s sterile, geometric art style evoked Windows 98-era utilitarianism. Cube textures were flat and unremarkable, with skins offering minor palette swaps (e.g., metallic grids or neon outlines). While functional, the visuals lacked charm or personality.

Atmosphere

Bomb3D’s ambiance was nonexistent. There was no music—only stark silence punctuated by generic “click” and “explosion” sound effects. The result felt less like a game and more like a math textbook exercise.

Sound Design

The audio design was perfunctory. Marking a bomb triggered a satisfying snap, but missed opportunities for escalating tension (e.g., rhythmic ticking near danger zones) left the experience feeling hollow.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Reception

Bomb3D garnered no professional reviews. Its sole player rating on MobyGames—3/5 stars—lamented its “lack of polish” and “untapped potential.” As shareware, it likely faded into obscurity without turning a profit.

Influence on the Industry

While Bomb3D itself left no ripples, its 3D puzzle concept foreshadowed later successes like 3D Minesweeper (2008) and Hexcells (2014). Modern indie darlings such as Baba Is You and Stephen’s Sausage Roll owe a debt to its experimental spirit, even if indirectly.

Conclusion

Bomb3D was a well-intentioned misfire. Its attempt to evolve Minesweeper into three dimensions introduced fresh challenges but faltered under technical limitations and a lack of refinement. For collectors of gaming oddities, it’s a fascinating artifact—a glimpse into an era when hobbyist developers could still carve niches in a rapidly corporatizing industry. Yet as a game, it remains a cubicle dweller’s daydream: functional, forgettable, and ultimately overshadowed by the classics it sought to redefine.

Final Verdict: A curious experiment, best left to historians and completists. ★★☆☆☆