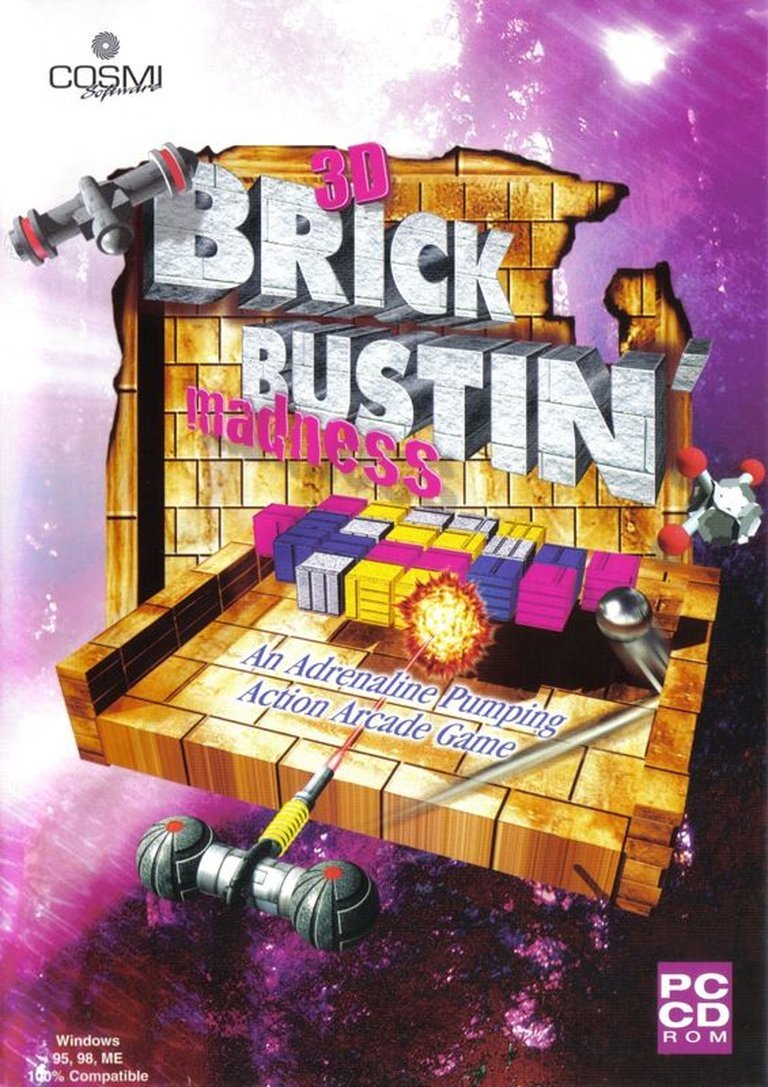

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Webfoot Technologies, Inc.

- Developer: Webfoot Technologies, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Paddle, Pong

Description

3D Brick Busters is a dynamic Breakout-style arcade game featuring 30 levels where players control a paddle to bounce a ball and destroy colorful blocks. Setting itself apart from traditional brick-breakers, this 1999 release introduces 3D movement, allowing vertical paddle navigation, alongside power-ups like cannons, ball holders, and temporary secondary paddles. While point-boosting items aid progression, players must also contend with disruptive effects like limited visibility and smiley-faced balls that temporarily hinder block-breaking capabilities.

3D Brick Busters: Review

A late-’90s Breakout reimagining that traded monumental impact for fleeting, kinetic joy—and left behind a curious footnote in the pantheon of arcade oddities.

Introduction

In 1999, as the gaming industry raced toward photorealism and sprawling 3D worlds, 3D Brick Busters arrived as a humble reinvention of the brick-breaking genre. Developed by Webfoot Technologies—a studio better known for shareware oddities than genre-defining hits—the game embodied the paradox of its era: ambitious enough to layer 3D spectacle atop Atari-era simplicity, yet shackled by the constraints of budget development. This review posits that while 3D Brick Busters failed to escape the gravitational pull of mediocrity, its inventive power-ups and kinetic design hint at unrealized potential, cementing it as a peculiar artifact of pre-millennial PC gaming.

Development History & Context

The Webfoot Paradox

Founded in the early ’90s, Webfoot Technologies operated on the periphery of gaming’s mainstream, producing low-budget titles like B.A.D. and Diablo intime that embraced eccentricity over polish. The studio’s 1999 output exemplified the shareware ethos: rapid development cycles, modest technical demands, and gameplay-first design. Yet 3D Brick Busters, led by programmer Cristian Soulos and producer Dana M. Dominiak, signaled a half-step toward modernity by leveraging early 3D acceleration—a gamble for a genre historically defined by 2D minimalism.

The 1999 Crucible

Released alongside titanic cultural phenomena like Half-Life and Final Fantasy VIII, 3D Brick Busters targeted a shrinking niche: casual PC gamers still clinging to CD-ROM compilations. The game’s tech specs—a CD-ROM drive, keyboard-only controls, and support for resolutions up to 640×480—reflected an industry in transition, straddling the death of DOS and the rise of DirectX dominance. Webfoot’s choice to adopt diagonal-down 3D perspective nodded to arcade successes like Marble Madness but sacrificed the clarity of pure top-down play.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Absence of Story

3D Brick Busters dispensed with narrative pretense. No protagonists, no conflict—just geometric annihilation for its own sake. This void was superficially filled by thematic level backdrops: early stages evoked sterile neon grids, while later arenas flirted with cyberpunk motifs (glowing circuits, industrial scaffolding). Retro Replay’s analysis suggested these shifts implied “zones,” though this abstraction served only to justify visual variety, not storytelling.

The Tyranny of Smiley Faces

The game’s sole nod to personality came through its penalty items, particularly the “smiley face” power-down that transformed destructive spheres into harmless bouncers. This fleeting absurdity—bricks adorned with cartoonish grins, balls stripped of purpose—became a darkly comic metaphor for futility: the player as Sisyphus, cursed to rally against a universe indifferent to their progress.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Breakout with Axes Unlocked

At its foundation, 3D Brick Busters adhered to Steve Wozniak’s 1976 Breakout formula: bounce a ball to shatter bricks. Webfoot’s innovation lay in adding vertical paddle movement, enabling players to dodge rebounds along the Y-axis—a subtle twist that demanded spatial awareness absent in pure 2D iterations.

Power-Ups: Salvation and Sabotage

The game’s most compelling systems were its power-ups:

– Cannons: Instantly vaporized brick clusters, rewarding aggression.

– Ball Holders: Temporarily suspended physics, granting strategic respite.

– Secondary Paddles: Deployed as rear guards against rogue rebounds.

Conversely, malicious items weaponized RNG chaos:

– Camera Downshift: Obscured 40% of the playfield, forcing predictive shots.

– Smiley Balls: Rendered projectiles non-destructive for 10 seconds.

This duality created frenetic highs (multi-ball cannon barrages) and punitive lows (back-to-back smiley transformations), accentuating the thrill of risk-replay compulsion.

Flawed Foundations

The diagonal camera introduced unintended friction. As Retro Replay noted, perspective distortion made judging ball trajectories unreliable, especially in later levels with staggered brick formations. Combined with keyboard-only controls (no mouse support), precision became a war of attrition rather than skill—a flaw exacerbated when penalty items forcibly altered the camera angle.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visuals: The 3D Mirage

Webfoot’s “3D” label belied the game’s rudimentary architecture: bricks were flat planes with basic texturing, while lighting effects (ambient glows, particle bursts) served as smoke-and-mirrors spectacle. Yet this minimalism birthed a surprising cohesion: primary-color bricks popped against gridded void backdrops, echoing the era’s arcade cabinets.

Sound Design: Chiptune Nostalgia

Chris J. Hampton’s soundtrack leaned into synthetic arpeggios and drum-machine loops, evoking the artificial cheer of early digital pinball machines. Sound effects—metallic brick cracks, power-up chimes—reinforced tactile feedback, though their repetitiveness grated during marathon sessions.

Reception & Legacy

The Silence Upon Release

No critic reviews surfaced at launch—a damning indictment of Webfoot’s marketing reach. Player impressions on forums like RetroReplay were polarized: some praised its “addictive chaos,” while others dismissed it as “Diet Arkanoid.” The game’s sole commercial afterlife came via 3D Game Pack (2003), a bargain-bin compilation burying it alongside forgotten puzzle titles.

The Ripple Effect

Though 3D Brick Busters failed to influence successors directly, its experiments presaged indie reinventions like Break Quest (2004) and Wizorb (2011)—titles that similarly weaponized power-ups and perspective shifts. Webfoot itself cycled the “3D Madness” branding into airport simulators and missile-dodge games, cementing a pattern of ephemeral novelty over lasting design.

Conclusion

3D Brick Busters occupies a paradoxical space: too modest to ascend beyond its genre constraints, yet too eccentric to dismiss entirely. Its attempts to modernize Breakout—vertical navigation, 3D presentation—feel like solutions in search of a problem, hampered by technical stumbles and a lack of coherent vision. And yet, in fleeting moments—a cannon erupting through a wall of cyan bricks, a last-second paddle save—it captures the primal joy of destruction that defines arcade gaming’s soul. For historians, it remains a vital case study in late-’90s shareware ambition; for players, a curiosity best experienced through the forgiving lens of nostalgia. Not a masterpiece, then, but a worthy digital relic—3 stars out of 5.