- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: DOS, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

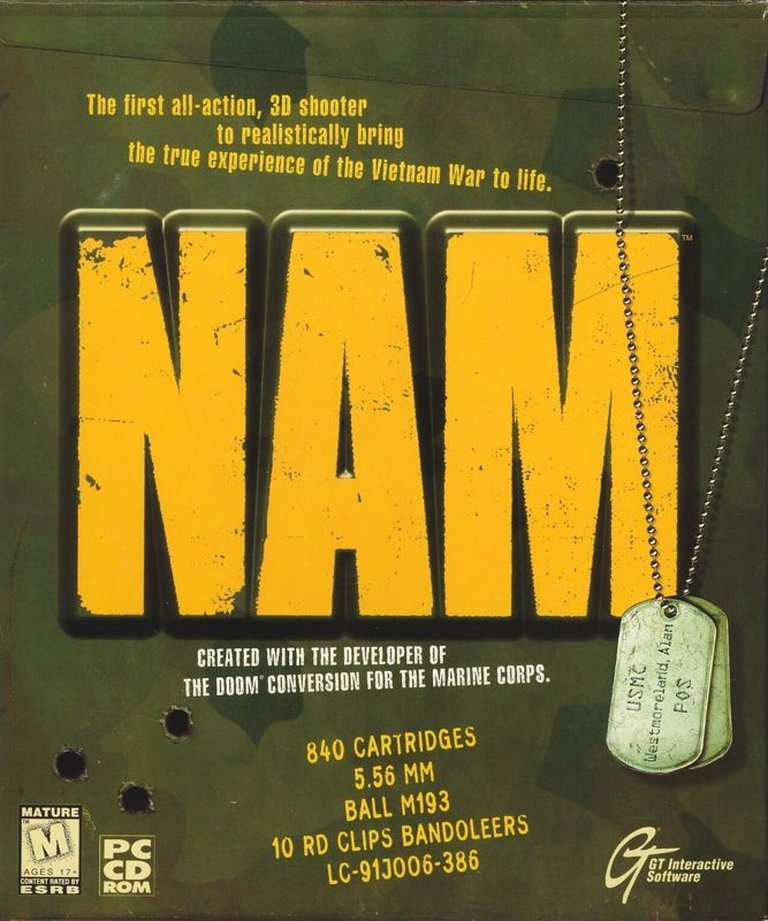

- Publisher: Brasoft Produtos de Informática Ltda., GT Interactive Software Corp., Night Dive Studios, LLC, Tommo Inc., Ziggurat Interactive, Inc.

- Developer: TNT Team

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Airstrikes, Mine detection, Shooter, Tactical Combat, Vehicle-mounted machine guns

- Setting: Cold War, Historical events, Jungle, Vietnam War

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

Set during the Vietnam War in 1966, NAM is a first-person shooter that follows Marine Corps sergeant Alan ‘The Bear’ Westmoreland, known for using stimulants to endure high-risk missions. Utilizing the Build engine, players navigate jungles, urban environments, and tunnel systems while engaging in firefights, evading ambushes, and defusing traps. Missions include urban combat, stealth operations, and surviving airstrikes, with weapons like the M16, M60, and LAW. Multiplayer modes such as Gruntmatch and Capture-the-flag offer soldier-type selection and team-based objectives across 19 levels.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy NAM

NAM Reviews & Reception

gamespot.com (40/100): NAM strives to deliver the fun and intensity of a first-person action game and the realism of a simulation – and because of that indecision it ultimately fails on both …

gamesreviews2010.com (90/100): Nam is a classic first-person shooter that puts players in the boots of a Marine Corps sergeant fighting in the Vietnam War. The game’s realistic graphics, intense gameplay, and immersive story have been praised by critics and players alike. If you are a fan of first-person shooters or war games, then you owe it to yourself to check out Nam.

NAM Cheats & Codes

PC Version

Enter cheat codes during gameplay. For level select, use the format NVALEVEL### where ### is the episode and level number.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| nvagod | God Mode |

| nvacaleb | God Mode |

| nvaclip | Toggle Clipping Mode |

| nvashowmap | Full Map |

| nvablood | All Weapons |

| nvunlock | Toggle All Locks |

| nvarate | Change Game Speed |

| nvadebug | Debug Mode |

| navlevel### | Level Select |

| nvamatt | Radioman Follows |

| nvduke | Toggle Radio |

DOS Version

Enter cheat codes during gameplay. Level select format: NVALEVEL101 = Episode 1, Level 1.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| nvablood | All Weapons |

| NVARATE | Change Rate |

| NVADEBUG | Debug |

| nvagod | God Mode |

| NVALEVELxxx | Leveljump |

| NVACLIP | No Clipping |

| NVAMATT | Radio |

| NVASHOWMAP | Shows the whole map |

| NVADUKE | Surprise |

| NVAUNLOCK | Toggle Locks |

NAM: A Fractured Mirror of Vietnam War FPS Ambition

Introduction

In the pantheon of Vietnam War-themed games, NAM (1998) stands as a bizarre artifact—a first-person shooter that dared to ask, What if Duke Nukem fought in the jungle? Developed by TNT Team and published by GT Interactive, NAM arrived at a time when the Build engine was gasping its last breaths, overshadowed by the rise of Quake II and Half-Life. This review posits that NAM is a paradox: a game with genuine aspirations to simulate the grunt’s experience of Vietnam, yet hamstrung by technological obsolescence, laughable design choices, and a tonal identity crisis. It is neither a successful homage to war nor a competent shooter, but its flaws make it a fascinating study of late-’90s FPS growing pains.

Development History & Context

From Mod to Retail: A Rocky Transition

NAM began life as Platoon TC, a total conversion mod for Duke Nukem 3D (1996). TNT Team’s vision was to transplant the chaotic intensity of the Vietnam War into a Build engine framework, leveraging its pseudo-3D environments and sprite-based combat. When GT Interactive acquired the rights, the project expanded into a commercial release, with input from U.S. Marine Sergeant Dan Snyder, known for his Doom military training mods.

The Build Engine’s Twilight

By 1998, the Build engine was a relic. Duke Nukem 3D had already pushed its limits in 1996, and the arrival of true 3D engines like Unreal and GoldSrc made NAM’s chunky sprites and raycasted environments feel archaic. Yet, TNT Team persisted, retrofitting the engine for dense jungles and tunnel warfare—a decision that led to claustrophobic level design and jarring visual compromises.

The Vietnam Game Void

The late ’90s saw few Vietnam War games (Shellshock: Nam ’67 would arrive in 2004). NAM aimed to fill this gap but lacked the budget and tech to compete with contemporaries like Medal of Honor (1999). Its release timing—sandwiched between genre-defining titans—sealed its fate as a commercial afterthought.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot: Super-Soldier Nonsense

Players assume the role of Alan “The Bear” Westmoreland, a Marine Corps sergeant genetically enhanced by the CIA to withstand combat stimulants. The premise veers into sci-fi absurdity, with Westmoreland described as a “super human war machine” battling Viet Cong hordes. This tonal whiplash—half gritty war drama, half B-movie schlock—undermines any attempt at authenticity.

Characters and Dialogue

NPC allies spout garbled radio chatter, while Westmoreland himself is a silent protagonist. The lack of character development reduces the war to a series of shooting galleries, devoid of emotional weight. Briefings feature poorly recorded voiceovers, leaning into camp rather than gravity.

Themes: War as a Carnival Ride

NAM’s themes oscillate between solemnity and farce. While levels simulate ambushes and minefields, the inclusion of Rambo-esque heroics and exaggerated explosions trivializes the conflict. The game’s attempt to balance realism (e.g., requiring mine detectors) with arcade action (e.g., unlimited sprinting) creates cognitive dissonance.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Combat: Build Engine Jank

The gunplay inherits Duke Nukem 3D’s floaty movement but lacks its polish. Weapons like the M16 and M60 feel weightless, while enemy AI alternates between omniscient snipers and mindless cannon fodder. The M79 grenade launcher, awkwardly repurposed from Duke’s shrink ray, exemplifies the game’s mechanical dissonance.

Innovations and Flaws

- Mine Detection: A novel idea, but mines are near-invisible amidst pixelated foliage.

- Airstrikes: Contextual radio commands add immersion, but their implementation is clunky.

- Multiplayer: Modes like Gruntmatch and Capture the Flag are functional but forgettable, plagued by lag and unbalanced loadouts.

UI and Progression

The HUD is a carbon copy of Duke Nukem 3D’s, complete with a facecam that grimaces with damage. Missions lack clear objectives, often devolving into key hunts—a holdover from ’90s FPS design that feels outdated even for 1998.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction: A Green Blur

The Build engine struggles to render jungles, with trees and bushes reduced to smears of lime-green pixels. Urban environments fare better, but textures are recycled liberally. Digitized sprites for Viet Cong soldiers clash with pre-rendered assets, creating a visual cacophony.

Sound Design: MIDI Missteps

Atom Ellis’ soundtrack leans on generic military marches and tension-building synths, but the MIDI format robs it of impact. Sound effects—gunshots, explosions—are tinny and lack punch, while voice acting is unintentionally comedic.

Atmosphere: Missed Potential

Moments of atmospheric brilliance peek through: napalm strikes illuminate the sky, and radio static punctuates firefights. Yet, these are undermined by technical limitations and a lack of narrative cohesion.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Panning

NAM scored a dismal 36% aggregate from critics. GameSpot (4/10) lambasted its “geriatric technology,” while PC Zone (28%) called it “a commercial Duke Nukem mod” undeserving of retail. Players were divided—some praised its challenge, but most decried its unfair difficulty and outdated design.

Influence and Follow-Ups

The 1999 sequel World War II GI fared even worse, cementing TNT Team’s reputation for mediocrity. Yet, NAM’s disastrous reception highlighted industry shifts: the death of sprite-based FPS, the rise of narrative-driven shooters, and the risks of commercializing mods.

Modern Reappraisal

Retro enthusiasts occasionally defend NAM as a “so bad it’s good” relic, but its 2014 re-release on GOG and Steam garnered little attention. It remains a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing execution.

Conclusion

NAM is a game at war with itself—a half-hearted simulation straining against the confines of a dying engine. Its attempts to blend realism with arcade action collapse under technical incompetence and tonal incoherence. Yet, as a historical artifact, it offers a glimpse into a pivotal era when FPS developers grappled with advancing technology and maturing narratives. NAM is not a good game, but its failures are instructive, a fractured mirror reflecting the genre’s awkward adolescence. For historians and masochists only.

Final Verdict: A 2/5—a fascinating misfire, best remembered as a footnote in the Build engine’s obituary.