- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

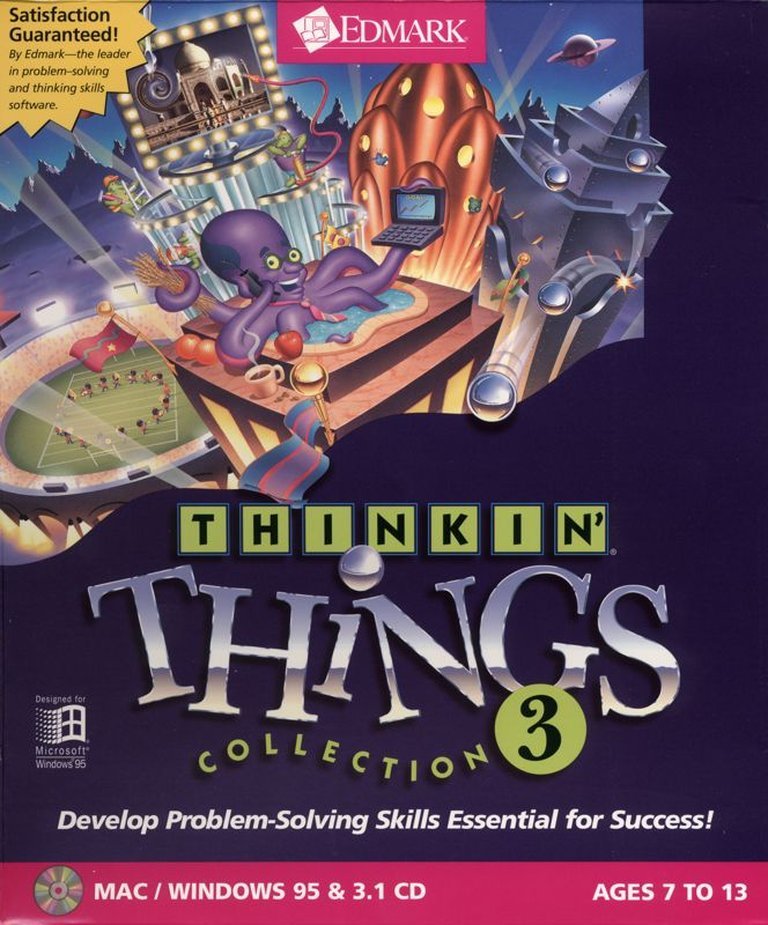

- Publisher: Edmark Corporation, IONA Software Limited

- Developer: Edmark Corporation

- Genre: Educational, Puzzle

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Analysis, Creative editing, Creativity, Deduction, Mystery-solving, Photo analysis, Physics-based puzzles, Programming, Reasoning, Trading

- Setting: Educational, Fantasy

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Thinkin’ Things Collection 3 is an educational game designed to engage children in problem-solving and creative thinking through a variety of interactive activities. Players explore five main challenges: Stocktopus, which teaches trading and strategy; Fripple Place, a mystery-solving task involving spatial logic; BLOX, focused on physics concepts like gravity and motion; Halftime Show, encouraging pattern creation and sequencing; and Photo Twister, which blends analysis with creative photo manipulation. The game adapts to the player’s skill level via its ‘Grow Slide’ feature, progressively increasing difficulty based on correct answers to foster critical thinking and deductive reasoning in a playful environment.

Gameplay Videos

Thinkin’ Things Collection 3 Free Download

Thinkin’ Things Collection 3: A Cerebral Playground for Future Problem-Solvers

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, when edutainment software flooded classrooms and living rooms, Edmark Corporation’s Thinkin’ Things Collection 3 stood apart. Released in 1995 as the culmination of a celebrated trilogy, it refined the series’ signature blend of cognitive challenges and whimsical creativity into a toolkit for young minds. More than a game, it was a digital incubation chamber for critical thinking, disguising rigorous logic puzzles and physics experiments beneath a veneer of playful absurdity. This review posits that Collection 3 represents a high watermark in constructivist learning software—a title that transcended its era’s drill-and-skill conventions to foster genuine curiosity and systemic reasoning.

Development History & Context

Edmark’s Vision and the 90s Edutainment Landscape

Edmark Corporation, already renowned for its Mighty Math and Millie’s Math House series, positioned Thinkin’ Things as a rebuttal to formulaic educational titles. Led by designers Scott Clough and Amy Schottenstein, the team prioritized “invisible learning”—activities where educational outcomes emerged organically from experimentation. The 36-person crew (per MobyGames’ credits) included artists like Karin Madan and composers Mike Bateman and Hiro Shimozato, whose work infused the game with a cohesive, child-friendly aesthetic.

Technological Ambitions and Constraints

Developed for Windows 3.x, 16-bit Windows, and Macintosh systems, Collection 3 leveraged the CD-ROM boom to deliver vibrant 256-color graphics and responsive drag-and-drop mechanics—a quantum leap from the floppy-disk limitations of its 1993 predecessor. However, hardware constraints necessitated simplicity: physics simulations in BLOX avoided complex calculations, while character animations relied on sprite-based efficiency. Despite this, Edmark squeezed every drop of interactivity from the era’s hardware, creating a benchmark for multimedia learning.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Absent Stories, Present Systems

Unlike narrative-driven contemporaries like Pajama Sam, Collection 3 jettisoned plot entirely. Its “narrative” was the player’s own cognitive journey. Each activity framed learning as a playful mystery:

– Fripple Place cast children as detectives solving “the mystery of the empty Fripple House” by deducing spatial relationships (e.g., “Westside Fripples are red”).

– Stocktopus recast economics as a cephalopod-powered trading game, rewarding strategic bartering.

– Photo Twister transformed photo editing into an alien-invasion whodunit.

Themes: Empowerment Through Experimentation

Beneath the surreal vignettes lay a unified thesis: thinking is a tool, not a chore. The game celebrated trial-and-error, with hints delivered via quirky character thoughts (e.g., Fripples whispering clues) rather than explicit instruction. This mirrored contemporary educational theory, particularly Seymour Papert’s “constructionism,” where knowledge is built through creation. Collection 3 didn’t teach facts—it taught how to think about systems, from gravity’s rules to conditional logic.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Activities as Cognitive Gyms

Five minigames formed the spine of Collection 3, each targeting distinct skills:

1. Stocktopus: A resource-trading simulator requiring multi-step planning (e.g., trading shells→feathers→hats to afford a telescope).

2. Fripple House: Logic puzzles demanding Boolean reasoning (e.g., “If a Fripple isn’t striped, it must be on the top floor”).

3. BLOX: A physics sandbox where players sculpt ramps and grooves to manipulate marbles, teaching cause-and-effect.

4. Halftime Show: A proto-programming exercise where sequencing commands (jump, spin) choreographed marching band performances.

5. Photo Twister: Pattern recognition via “spot the difference” puzzles, with creative tools to remix images.

The Adaptive “Grow Slide”

Edmark’s masterstroke was the Grow Slide, a dynamic difficulty system in Stocktopus, Fripple Place, and Photo Twister. Correct answers escalated challenges: Fripple clues grew more complex, Stocktopus trades required longer chains, and Photo Twister aliens employed subtler alterations. This created a personalized curve that avoided frustration without coddling—a rarity in mid-90s edutainment.

Controlled Freedom, Limited Replay

While activities offered open-ended experimentation (e.g., BLOX’s marble tracks), the lack of overarching goals or scoring systems diminished long-term engagement for some. As TERC noted, the absence of “competitive play or story progression” made it feel more like a toolbox than a game—a strength for educators but a potential weakness for reward-driven players.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Aesthetics of Curiosity

Edmark’s art team crafted a Kandinsky-meets-cartoons aesthetic:

– Fripples resembled beanbag creatures in neon hues, their House a Mondrian-esque grid.

– Stocktopus merged a Wall Street trader with Jules Verne flair, operating from a submarine-like booth.

– BLOX’s metallic textures and clanging sound effects evoked a miniature industrial lab.

This visual diversity—unified by bold colors and simplified shapes—created distinct “cognitive zones” while maintaining coherence.

Sound as Feedback

Audio designer Mike Bateman used sound as pedagogical reinforcement:

– Triumphant brass stings celebrated correct Fripple placements.

– Marbles in BLOX emitted weighty rolls and clinks, grounding physics in sensory feedback.

– Halftime Show’s interactive orchestra let players compose rhythms, tying auditory creativity to logical sequencing.

Voice acting (e.g., Stocktopus’ faux-radio chatter) added warmth without condescension—a stark contrast to robotic edutainment peers.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Impact

Collection 3 earned a 70% critics’ average on MobyGames, with All Game Guide praising its “excellent” blend of learning and fun (80/100). MacUser crowned it 1995’s Best Children’s Software, while CODiE Awards honored it as Best Education Software in 1996. Commercially, it thrived in schools and homes, buoyed by Edmark’s reputation—series sales contributed to the franchise’s 18 awards by 1997 (per Wikipedia).

Long-Term Influence

The game’s legacy lies in its design philosophy:

– Sandbox Learning: Titles like Kerbal Space Program and Dreams echo BLOX’s embrace of playful experimentation.

– Adaptive Difficulty: The Grow Slide presaged modern systems like Prodigy Math’s AI-driven challenges.

– Coherent Aesthetics: Modern “cozy games” (A Short Hike, Scribblenauts) inherit its focus on inviting, stress-free worlds.

Yet, its lack of narrative scaffolding limited mainstream nostalgia; unlike Oregon Trail or Carmen Sandiego, Thinkin’ Things remains a cult classic among educators and retro enthusiasts.

Conclusion

Thinkin’ Things Collection 3 is a time capsule of 90s edutainment idealism—a game that trusted children to learn by doing, not memorizing. Its activities, while mechanically simple by modern standards, were revolutionary in treating young players as competent problem-solvers, not passive recipients. Flaws like repetitive loops and minimal extrinsic rewards prevent it from universal appeal, but as a case study in stealth pedagogy, it remains unmatched. For historians, it’s a pivotal artifact in the shift from instructionist to constructivist learning software. For players, it’s a vibrant reminder that thinking—when framed as play—can be its own reward.

Final Verdict: A flawed yet visionary title that deserves its place in the pantheon of educational innovators, even if its star shines brightest in archival retrospectives.