- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

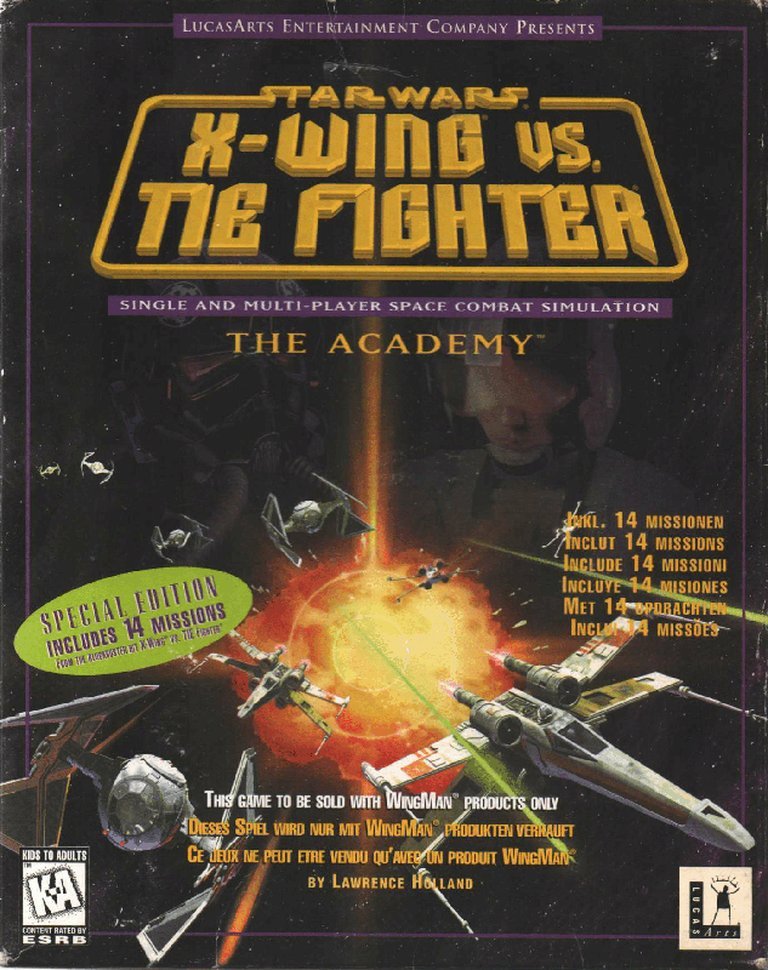

- Publisher: LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC

- Developer: Totally Games, Inc.

- Genre: Action, Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Flight Simulation, Mission-based, Space combat, Vehicular combat

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

Star Wars: X-Wing Vs. TIE Fighter – Flight School is a demonstration version of the 1997 space combat simulator, offering 14 missions (7 playable in multiplayer) from the full game. Set in the Star Wars universe, it pits Rebel Alliance X-Wing pilots against Imperial TIE Fighters in intense dogfights. This limited edition was distributed as part of the X-Wing Collector Series, bundled with Logitech hardware, and given away with select Star Wars game purchases at Best Buy stores.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter – Flight School

PC

Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter – Flight School: An Archaeological Dig into Star Wars’ Multiplayer Experiment

Introduction

In the annals of Star Wars gaming, the X-Wing series stands as a titan—a saga where players didn’t just watch the Galactic Civil War, but lived it. Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter – Flight School (1997) occupies a peculiar niche in this lineage: a stripped-down technical showcase that distilled Totally Games’ ambitious multiplayer vision into a 14-mission sampler. Serving as a demo, a hardware bundle freebie, and a footnote in the X-Wing Collector Series, Flight School is less a game than an artifact—a snapshot of an era when LucasArts gambled on multiplayer as the future of space combat sims. This review excavates its design, context, and legacy, arguing that Flight School is a fascinating but flawed time capsule: a testament to bold innovation hamstrung by technological constraints and audience expectations.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

Developed by Totally Games under Lawrence Holland’s direction, X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter (XvT) represented a seismic shift for the series. While X-Wing (1993) and TIE Fighter (1994) had pioneered narrative-driven, single-player space combat, XvT was engineered as a multiplayer-first experience in an era when internet gaming was in its infancy, dominated by LAN parties and dial-up modems. As David Wessman, lead mission designer, later admitted, the team deliberately sidelined storytelling, believing pure competitive dogfights would suffice [Wikipedia, XvT].

Flight School emerged alongside XvT’s turbulent release. LucasArts bundled it with Logitech hardware and offered it as a promotional item at Best Buy to seed interest [MobyGames]. It also served as the gateway to the X-Wing Collector Series (1998), which retrofitted the original X-Wing and TIE Fighter with XvT’s engine, swapping Gouraud shading for rudimentary texture mapping [Wikipedia, X-Wing Collector Series]. Technically, XvT demanded joysticks, high-resolution SVGA monitors, and—for multiplayer—a tolerance for unstable internet protocols. As programmer Peter Lincroft noted, syncing real-time data for eight players in open space (unlike Doom’s walled corridors) required Herculean coding [Wikipedia, XvT].

The 1997 Gaming Landscape

The mid-90s PC boom brought both opportunity and chaos. Quake (1996) popularized online deathmatches, while Freespace (1998) would soon elevate narrative-driven space sims. LucasArts’ bet on multiplayer felt prescient—but XvT’s lack of a campaign drew ire. Flight School, as a demo, crystallized this tension: a polished slice of tech without the meal.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Void Where Story Should Be

While the full XvT eventually received narrative scaffolding via the Balance of Power expansion (adding dueling Rebel/Imperial campaigns), Flight School exists in a thematic vacuum. Without cutscenes, characters, or context, its 14 missions reduce the Galactic Civil War to abstract skirmishes: defend convoys, intercept warheads, duel in asteroid fields. The absence of TIE Fighter’s moral ambiguity or X-Wing’s heroism renders the experience sterile—a flight simulator divorced from Star Wars’ mythos [Player Reviews, MobyGames].

Themes of Asymmetry & Loyalty

Where prior games explored ideology (Rebel idealism vs. Imperial duty), Flight School focuses purely on factional asymmetry. Rebel craft (X-Wings, Y-Wings) rely on shields and versatility, while Imperial TIEs trade durability for speed and numbers. This dynamic shines in multiplayer—where human pilots amplified these roles—but feels hollow against AI opponents criticized as “perfect but slowed down to feign humanity” [Squakenet].

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Training Wheels for the Stars

Flight School’s 14 missions—seven playable solo or via LAN/modem—function as a microcosm of XvT’s systems:

– Starfighter Management: Power allocation, shield management, and weapon toggling return, demanding tactical nuance amid chaos.

– Multiplayer Framework: Supporting 2-4 players (vs. XvT’s 8), modes like Team Dogfight and Co-Op vs. AI hinted at the full game’s potential [MobyGames Specs].

– Mission Design: Missions like “Warhead Interception” (with a secret pizza-delivery Easter Egg) showcase clever scripting, but repetitive objectives (“destroy all enemies”) lack escalation [Wikipedia].

UI & Accessibility

The HUD mirrors XvT’s complex layout—a double-edged sword. Veterans praised its granular control (customizable joystick inputs, squad commands), but newcomers faced a steep curve. Flight School’s lack of tutorials (beyond basic controls) felt jarring, as noted by critics: “A no-story simulator for experts” [Player Reviews, MobyGames].

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visuals: Textures Over Soul

XvT’s engine brought texture-mapped ships and dynamic lighting to the series—technically superior to TIE Fighter’s Gouraud shading, but artistically divisive. While capital ships like Star Destroyers loomed impressively, the “grotty” textures and flat nebulas lacked the painterly grandeur of prior games [Squakenet]. Flight School inherited these assets, offering a crisp but impersonal rendition of the Star Wars universe.

Sound Design: Nostalgia as Crutch

Peter McConnell’s score repurposed John Williams’ themes via the iMUSE system, dynamically adjusting to gameplay—a series hallmark. Sound effects, from TIE screams to laser blasts, remained iconic. Yet without narrative stakes, these elements felt decorative, not immersive.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception & Commercial Performance

The full XvT earned mixed reviews. Edge (90/100) praised its “interstellar deathmatch” potential, while Next Generation (3/5) lamented squandered depth. It sold 286,000 copies in 1997—a commercial success but a step down from TIE Fighter’s acclaim [Wikipedia]. Flight School, as a demo, escaped direct critique but mirrored its parent’s flaws: players called it “frustrating, pointless” without multiplayer buddies [MobyGames Reviews].

Long-Term Influence

XvT’s multiplayer DNA influenced X-Wing Alliance (1999) and modern throwbacks like Squadrons (2020). Its canceled 2009 HD remake foreshadowed the industry’s nostalgia mining [Wikipedia]. Yet Flight School remains a curiosity—a proving ground for tech later perfected elsewhere.

Conclusion

Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter – Flight School is gaming archaeology: a relic of a crossroads where LucasArts prioritized multiplayer ambition over storytelling. As a demo, it showcased cutting-edge tech but embodied the compromise that limited XvT’s appeal—space combat refined to mechanical brilliance yet stripped of Star Wars’ soul. While overshadowed by its predecessors and successors, Flight School merits recognition as a bold, if flawed, experiment—one that laid the networking groundwork for today’s online sims. For historians, it’s essential; for pilots seeking the Rebellion’s heart, stick with TIE Fighter.