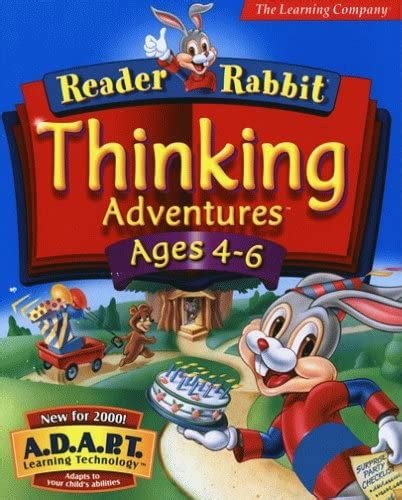

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Learning Co., Inc., The

- Developer: Learning Co., Inc., The

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: Fixed

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: North America

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

In ‘Reader Rabbit: Thinking Adventures Ages 4–6’, players join Reader Rabbit and friends as they prepare a surprise birthday party for Sam the Lion, who believes everyone has forgotten his special day. The game features eight educational mini-games set in locations like Owl’s Treehouse, Papa Bear’s Store, Babs’ Kitchen, and Pierre’s Studio, where children aged 4–6 develop logic, pattern recognition, and grammar skills. Completing each activity twice earns party items, culminating in a festive celebration for Sam.

Gameplay Videos

Reader Rabbit: Thinking Adventures Ages 4–6 Reviews & Reception

superkids.com (80/100): This simple, but cute program works well with preschoolers and early elementary school students.

Reader Rabbit: Thinking Adventures Ages 4–6: Review

Introduction

In the golden era of ’90s edutainment, Reader Rabbit: Thinking Adventures Ages 4–6 emerged as a cornerstone of early childhood learning. Released in 1999 by The Learning Company, this title blended whimsical storytelling with foundational cognitive skill-building, cementing its place in the pantheon of nostalgic educational software. More than a game, it was a gateway to critical thinking for preschoolers—a digital playground where logic puzzles masqueraded as party preparations. This review explores how Thinking Adventures balanced pedagogy and play, interrogating its design, legacy, and enduring charm.

Development History & Context

The Learning Company’s Vision

Developed by The Learning Company—a pioneer in educational software since 1980—Thinking Adventures arrived during a period of corporate tumult. Having been acquired by SoftKey in 1995 and later sold to Mattel in 1998, the studio faced pressure to streamline costs while expanding its flagship Reader Rabbit series. Thinking Adventures was part of a broader push to integrate “A.D.A.P.T. Learning Technology,” a dynamic system that adjusted difficulty based on player performance, though this iteration notably omitted the “Personalized” branding seen in contemporaries like Reader Rabbit Math Adventures.

Technological Constraints

Targeted at Windows and Macintosh systems, the game leveraged the era’s modest hardware: 256-color SVGA displays, CD-ROM drives, and 16MB RAM. These constraints shaped its design—static 2D screens, point-and-click navigation, and Smacker video cutscenes. Yet, these limitations birthed creativity: hand-drawn character art by Frank Cirocco (inked by Mick Gray) and a focus on intuitive UI ensured accessibility for non-readers.

The Edutainment Landscape

The late ’90s saw edutainment straddle commercial viability and educational rigor. Thinking Adventures competed with JumpStart and Carmen Sandiego, but distinguished itself through narrative-driven minigames. Released alongside Reader Rabbit: Playtime for Baby and preceding Learn to Read with Phonics (2000), it filled a developmental niche—teaching logic, patterns, and categorization through joyful repetition.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Birthday Surprise Saga

The plot centers on Reader Rabbit orchestrating a surprise party for Sam the Lion, convinced his friends forgot his birthday. This premise—innocent yet emotionally resonant for children—unfolds across 2D environments: Owl’s Treehouse, Papa Bear’s Store, Babs’ Kitchen, and Pierre’s Studio. Each locale ties activities to thematic party prep: decorating cookies, wrapping gifts, or choreographing dances.

Characters as Pedagogical Archetypes

- Reader Rabbit: The empathetic organizer, modeling collaboration.

- Sam the Lion: A naive foil, his vulnerability teaching empathy.

- Mat the Mouse, Babs the Beaver, et al.: Specialized roles (e.g., Babs’ baking) subtly reinforce gendered stereotypes but diversify skill exposure.

Dialogue, voiced by talents like Jeanne Hartmann (Reader) and Roger L. Jackson (Spike), balances simplicity with warmth. British localizations, including Justin Fletcher’s Pierre, added regional charm but retained core educational beats.

Subtext: Critical Thinking as Celebration

Beneath the birthday veneer lies a treatise on problem-solving. Activities reframe abstract concepts—sequencing, pattern recognition—as tangible goals (e.g., “Paint wrapping paper to unlock a gift”). The finale—Sam’s party—rewards perseverance, though some players critique its anticlimactic payoff compared to the buildup.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Prep, Play, Progress

Eight minigames span four venues, each requiring completion twice to collect 18 party items. The A.D.A.P.T. system auto-adjusted difficulty, while manual selection of three tiers (1–3) empowered parental oversight:

1. Owl’s Treehouse

– Mouse Dance: Mimic dance patterns (movement sequencing).

– Donkey Directions: Grid navigation using directional tokens.

2. Papa Bear’s Store

– Toy Sort: Categorize toys into Venn-like hula hoops.

3. Babs’ Kitchen

– Cookie Creator: Decorative pattern matching.

Activities escalate in complexity—e.g., Banner Builder demanding players differentiate cards by two attributes (color and shape) at higher levels.

UI & Accessibility

A point-and-click interface minimized reading dependency. The radial “Pop” menu (a series staple) tracked progress, while a Skills Report quantified learning outcomes—fonts and icons oversized for young eyes. Flaws emerged in repetition: completing identical minigames for multiple items risked monotony, a trade-off for skill reinforcement.

Rewards & Replayability

A print shop allowed crafting real-world party invites, extending engagement beyond the screen. Post-game, hidden “animated surprises” rewarded exploration, though limited narrative branching kept replay value modest.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design: A 90s Edutainment Aesthetic

Wordville’s aesthetic—primary colors, rounded edges, and anthropomorphic characters—mirrored contemporaries like Freddi Fish. Locations like the museum entrance and Babs’ Kitchen exuded coziness, though reused assets from Reader Rabbit 1st Grade betrayed budget constraints. Pierre’s inconsistent fur color (red beret vs. original design) hinted at rushed production.

Soundscape: Pedagogy as Melody

Scott Lloyd Shelly’s soundtrack—jaunty MIDI tunes like Treats & Cookies Song—complained voice acting’s clarity. Diegetic sounds (balloon pops, cookie decor clicks) enhanced tactile feedback, while British voiceovers offered regional flavor.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Impact

- Reviews: SuperKids praised its “essential learning skills” (4/5 Educational Value), though noted the party’s underwhelming climax.

- Sales: Bundled in compilations (e.g., Adventure Workshop: Preschool-1st Grade) and 2008 Chick-fil-A kids’ meals, it reached broad audiences.

- Awards: While lacking the acclaim of Reader Rabbit 1st Grade’s Parent’s Choice Gold, it secured a foothold in homes and classrooms.

Cultural Footprint

Thinking Adventures epitomized late-’90s edutainment: a bridge between workbook rigor and digital interactivity. It innovated with A.D.A.P.T. but avoided risks—no radical departure from series norms. Today, emulated copies circulate among nostalgic millennials, while its absence from digital storefronts (unlike Reader Rabbit Kart Racing) consigns it to abandonware lore.

Conclusion

Reader Rabbit: Thinking Adventures Ages 4–6 remains a poignant artifact of its era—a time when learning software balanced affection with aspiration. Its design, though constrained by technology and repetition, succeeded in making logic tangible for preschoolers. While overshadowed by franchise titans like Interactive Reading Journey, its legacy lies in distilling critical thinking into birthday-themed joy. For historians, it captures The Learning Company’s ethos; for players, it’s a pixelated heirloom of childhood curiosity. Verdict: A warmly effective, if dated, primer in cognitive play.