- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: FM Towns, Windows

- Publisher: Fujitsu Australia Ltd., Fujitsu ICL Computer GmbH, Fujitsu ICL Computers Ltd., Fujitsu ICL Computers S.A., Fujitsu Interactive, Inc., Fujitsu Limited

- Developer: Believable Agent Project Dept./Fujitsu Limited, Fujitsu Laboratories Ltd.

- Genre: Pet, Simulation

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Caretaking, Day, night cycle, Reward System, Speech Recognition, Virtual pet

- Setting: Magic Planet, Virtual world

Description

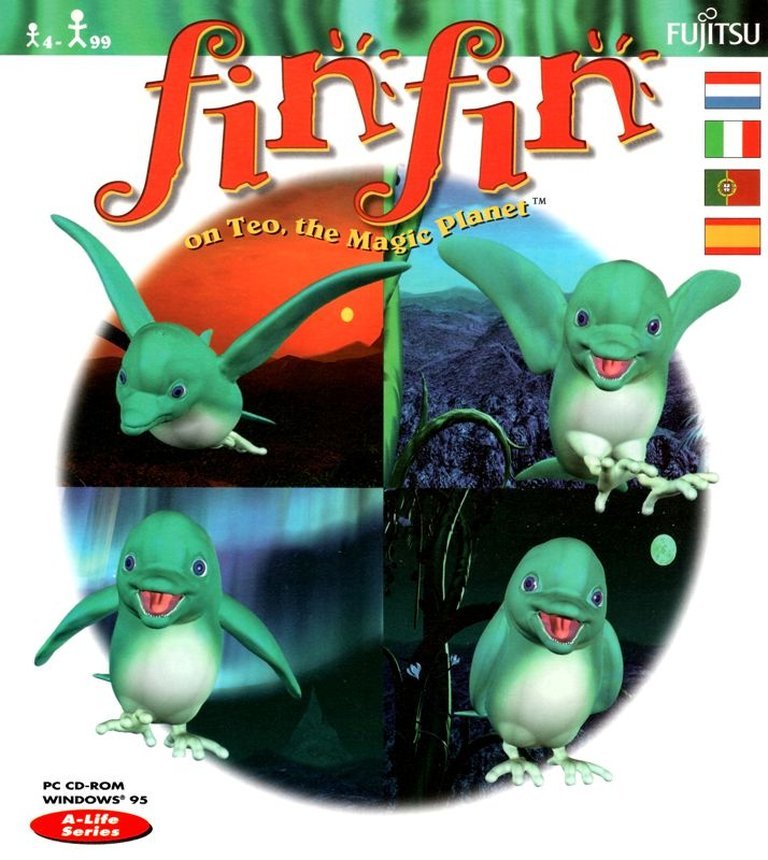

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet is a virtual pet simulation game released in 1995. Players care for Fin Fin, a virtual creature that responds to speech patterns, requiring feeding, sleep, and interaction to maintain its happiness. Set in a magical virtual world, Fin Fin can encounter other animals, affecting its mood and leading to rewards like singing or performing tricks when content.

Gameplay Videos

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet Free Download

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet Cracks & Fixes

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet Patches & Updates

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet Reviews & Reception

wsspaper.com : The game was good but I had the problem of only playing at night so Fin Fin never came out or was active enough to do stuff with him.

superkids.com : Fin Fin is a bit difficult to get to know, however, and in some cases the initial input required to strike a lasting friendship proved to be too much.

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet – A Forgotten Experiment in Digital Companionship

Introduction

In an era dominated by Tamagotchi mania and early AI experimentation, Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet (1996) emerged as a bold, if flawed, vision of interactive virtual life. Developed by Fujitsu, this hybrid virtual pet and artificial life simulator dared to blend speech recognition, environmental storytelling, and a creature unlike anything seen before: Fin Fin, a melancholic bird-dolphin hybrid. Though dismissed by critics as a half-baked novelty, the game has since cultivated a cult following for its haunting beauty and proto-Nintendo Wii ambitions. This review argues that Fin Fin is less a “game” and more a time capsule of mid-’90s techno-optimism—a flawed but fascinating step toward emotional AI companions.

Development History & Context

Fujitsu’s Multimedia Gambit

In the mid-1990s, Fujitsu—better known for hardware—sought to dominate the nascent “multimedia” market. The Believable Agent Project behind Fin Fin was helmed by executive producer Macoto Tezka (son of Astro Boy creator Osamu Tezuka) and leveraged seven years of R&D into AI and CGI. With a $3.6 million budget, half allocated to multimedia ventures, Fujitsu positioned Fin Fin as a flagship for its “experiential software” line.

Technological Ambition in a Low-Poly World

For 1996, Fin Fin was a technical marvel. Its titular creature was rendered in 40,000 polygons at 10 FPS, while background scenes purportedly used 1 million polygons—a staggering claim for pre-GPU PCs. The bundled SmartSensor microphone and camera (a precursor to the Xbox Kinect) allowed rudimentary speech and motion detection. Yet, these innovations clashed with hardware limits: German players found the sensor nonfunctional due to faulty drivers, and FM Towns/Win95 installations often crashed.

The Tamagotchi Shadow

Released alongside Bandai’s global Tamagotchi craze, Fin Fin struggled to define itself. While Tamagotchi offered bite-sized responsibility, Fin Fin asked players to nurture a cryptic, slow-burn relationship with a creature that often ignored them. Fujitsu’s marketing leaned into New Age mysticism, calling Fin Fin a “virtual mood ring” attuned to human emotion—a pitch that confused mainstream audiences.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Loneliest Alien

Fin Fin has no traditional plot. Players are cast as passive observers on Teo, an alien planet where Fin Fin roams forests, rivers, and valleys. The “goal” is to earn his trust through patience: speaking softly, offering food (Lemo berries), and avoiding sudden movements. Over time, Fin Fin might introduce his family: wife Finnina and son Finfin Junior, who only appear in the rare 6-world edition.

Themes of Isolation and Connection

Fin Fin’s design—a fragile, hybrid creature—evokes themes of ecological harmony and alienation. His sadness when neglected mirrors Tamagotchi’s guilt-tripping but feels more melancholic, less transactional. The game’s sparse dialogue (Fin Fin “speaks” in whistles) and reliance on nonverbal cues—averted gazes, hesitant chirps—turn interaction into a meditative act. Critics derided this as “not fun,” but players praised its therapeutic quality, likening it to birdwatching or caring for a shy animal.

Environmental Storytelling

Teo’s ecosystem teems with subtle drama. Gminfly (a flying orca) menaces Fin Fin’s nest; seasonal events like double lunar eclipses occur on real-world dates. Yet, the game never explains these elements, leaving players to piece together Fin Fin’s world through observation—a radical design choice that polarized audiences.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Frustrating Art of Conversation

Fin Fin’s touted speech recognition was primitive: it measured tone and volume, not words. A gentle voice pleased Fin Fin; shouting scared him. The 1–5 keys emitted attention-grabbing tones, while spacebar offered berries. Later versions let players record custom sounds (6–0 keys), but this feature was buried in menus.

Time, Weather, and the Tyranny of Realism

Like Animal Crossing, Fin Fin synced to real-world time. Nighttime play yielded empty forests; thunderstorms and northern lights arrived unpredictably. This “living world” clashed with the era’s save-and-quit expectations—Fin Fin might vanish for days if neglected.

UI Woes

The interface was notoriously opaque. Players accidentally skipped tutorials, missed Fin Fin’s friendship meter (hidden behind the B key), and struggled with unresponsive controls. German players couldn’t use the sensor, crippling immersion.

World-Building, Art & Sound

A Hand-Painted Alien Eden

Art director Yla Okudaira crafted Teo as a low-poly utopia. The Amile Forest’s willow-like trees swayed under Technicolor skies; the Rem River Bank shimmered with procedural water effects. Each locale felt alive: musical plants performed concerts when Fin Fin was absent, and berries ripened in real-time.

Sound Design as Emotional Language

Composer Chuji Akagi gave Fin Fin an ethereal whistle that shifted with his mood—playful trills when happy, dissonant cries when distressed. The soundtrack blended ambient nature sounds with minimalist synth, evoking Studio Ghibli’s tranquil moments.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Backlash

Reviews were brutal. Game Revolution (0/100) called it “cute doesn’t cut it,” lambasting its lack of goals. GameStar (40/100) deemed Fin Fin “zickig” (finicky), while players lamented crashes on Win95. It sold 30,000 copies in Japan—a flop for Fujitsu.

Cult Resurrection

Today, Fin Fin thrives in niche circles. Lost media hunters scour eBay for copies (one sealed edition sold for $1,000 in 2025), while modders restore broken features. Its influence echoes in AIBO, Nintendogs, and indie gems like Chicory: A Colorful Tale.

Conclusion

Fin Fin: On Teo, the Magic Planet is a paradoxical artifact—a technical triumph hamstrung by poor UX, a “game” that rejects gamification. Its true legacy lies in its ambition: to create not a toy, but a digital being worthy of empathy. For every player bored by its pacing, another found solace in its quiet world. In an age of algorithmic attention grabs, Fin Fin’s demand for patience feels almost radical—a reminder that connection, virtual or real, cannot be rushed.

Final Verdict: A 3/5 for execution, but a 5/5 for historical significance. Essential for AI historians, frustrating for everyone else.