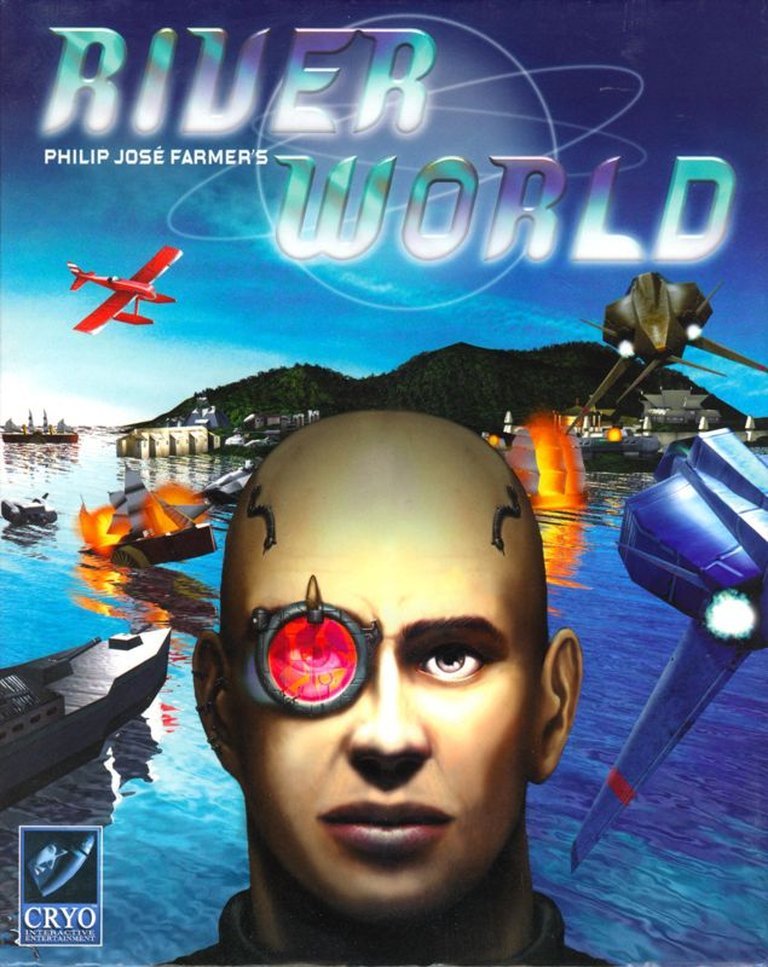

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cryo Interactive Entertainment

- Developer: Cryo Interactive Entertainment

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Point and select, Real-time strategy

- Setting: Fantasy, Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

Set in Philip José Farmer’s literary universe, ‘Riverworld’ is a 3D real-time strategy game where humanity is resurrected on a planet dominated by a single winding river. Players assume the role of British explorer Richard Francis Burton, tasked with evolving humanity from prehistoric times to a futuristic society. Gameplay involves building settlements, conquering territories to advance technological eras, interacting with historical figures, and defending against rival factions—all while navigating a visually immersive, though mechanically challenging, 3D environment.

Gameplay Videos

Philip José Farmer’s Riverworld Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (60/100): The concept of the game is great. The map is split between different areas that give access to better technologies, which in turn improves the chance of conquering enemy territory.

en.wikipedia.org (65/100): “RiverWorld brings a rich atmosphere to build a intuitive realtime strategy with some complex role playing concepts.”

Philip José Farmer’s Riverworld: A Forgotten Frontier of 3D RTS Ambition

Introduction

In the golden age of real-time strategy, when Age of Empires and Command & Conquer dominated the landscape, Philip José Farmer’s Riverworld (1998) emerged as a flawed but fascinating anomaly. Developed by Cryo Interactive—known for atmospheric, narrative-driven titles like Dune and Atlantis—Riverworld dared to fuse Farmer’s existential sci-fi epic with 3D RTS innovation. This review argues that while Riverworld’s conceptual ambition and thematic depth remain compelling, its technical limitations, erratic pacing, and interface missteps solidified its reputation as a cautionary tale of unrealized potential.

Development History & Context

Cryo’s Risky Gambit

Cryo Interactive, a French studio celebrated for lavish storytelling (Dragon Lore, EcoQuest), ventured into uncharted territory with Riverworld. Tasked with adapting Farmer’s sprawling philosophical saga—where 36 billion humans are resurrected along an endless river—the team, led by director/programmer Fabrice Bernard, faced Herculean challenges. The game was built entirely in assembly language (per Next Generation), a technical feat reflecting Cryo’s commitment to optimization but limiting flexibility. Released in June 1998, Riverworld arrived amidst Starcraft and Myth’s heyday, aiming to differentiate itself with 3D environmental control and a cerebral narrative.

Technological Constraints

The game’s 3D engine, while pioneering for RTS, strained under Cryo’s ambitions. A “free camera” system allowed panning and zooming, but poor draw distance and a unit-following camera drew criticism (PC Zone: “unübersichtlich” [unmanageable]). Cryo prioritized scale—simulating thousands of units across eras—but sacrificed stability. The decision to omit voice acting and simplify combat animations (PC Joker: “lächerliche Kampfszenen” [ridiculous battles]) further exposed budget constraints.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Meta-Historical Stage

Faithful to Farmer’s novels, Riverworld casts players as Sir Richard Francis Burton (a dead ringer for Timothy Dalton), who must unite resurrected humans—from cavemen to 21st-century figures—against rivals like Hermann Göring. The plot transcends typical RTS fare: Capturing territories (symbolized by alien “Grail Stones”) unlocks 11 technological eras, advancing from Wood to Uranium Age, each tied to real-world innovators (e.g., Jules Verne enables the Electric Age).

Philosophy vs. Mechanics

Thematic richness clashed with execution. Dialogues with historical figures (Via pop-ups; no voiceovers) aimed to explore humanity’s cyclical violence and progress but felt undercooked (PC Player: “Dialoge ohne Sprachausgabe” [text-only dialogues]). Critics noted dissonance: Farmer’s existential critique of resurrection became a routine tech tree. Conceptually brilliant—forcing players to reconcile advancement with moral decay—Riverworld’s narrative potential drowns in micromanagement.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Innovation and Frustration

Riverworld’s core loop mirrors Age of Empires: gather resources (wood, stone), build structures (houses, barracks), and conquer territories. Its novelties, however, were double-edged:

– 3D Unit Control: Assigning roles (laborer, soldier, scientist) to individuals enabled deep specialization but overwhelmed players. As MobyGames reviewer Luis Silva noted, pace escalates “too fast” beyond 10 units.

– Territory Conquest: Controlling Grail Stones unlocks adjacent zones, compelling strategic expansion. Yet the AI’s relentless aggression (even at “low” difficulty) destabilized balance (Attack Games: “utmanande” [challenging] became “frustrerande”).

– Era Progression: Recruiting luminaries like Verne to research techs (e.g., electricity) should’ve been revelatory. Instead, locating these “special units” in fogged terrain proved tedious (Game Over: “hunting every white dot”).

Interface: A Canvas of Chaos

The UI drew universal ire. Oversized, vague icons clashed with a cluttered mini-map (PC Action: “sperriges Interface” [clunky interface]). Camera controls—alternating between Burton’s first-person view and isometric tracking—failed both roles (Power Play: “eigenwillig” [capricious]). Worst was the absence of speed settings or multiplayer, sidelining replayability.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visionary Aesthetics, Dated Execution

Cryo’s depiction of a 10,000-mile river valley, rendered in early 3D, oscillates between haunting and haphazard. Rolling hills and Grail Stones evoke Farmer’s alien mystique, but low-poly units and repetitive structures dull immersion. Supporting 3DFX/Voodoo graphics, Riverworld’s water effects impressed contemporary critics (PC Games: “metallisch-reflexive Flüsse” [metallic-reflective rivers]), while explosions and crumbling buildings underwhelmed (GameStar: “lieblose Grafik” [careless graphics]).

Stéphane Picq’s Sonic Ambiance

The saving grace was composer Stéphane Picq (Dune, Lost Eden), whose score layered tribal percussion with synth melancholy—a haunting counterpoint to the River’s nihilism. Sadly, sparse sound effects (missing worker audio, silent battles) undermined atmosphere.

Reception & Legacy

Mixed Reviews, Muted Impact

Riverworld garnered a 60% MobyScore from critics. German outlets praised ambition (PC Action: 74%), while English reviewers skewered execution (PC Zone: 65%, “initially entertaining diversion”). Commercial failure (Der Spiegel: “komplett verkauften sich nicht” [didn’t sell]) buried Cryo’s RTS experiment. Today, it lingers as a cult oddity—admired for ideation (integrating RPG dialogue into RTS) but lambasted in retrospectives (Rock Paper Shotgun: “a mess”).

Influence: A Ripple, Not a Wave

Its legacy lies in cautionary lessons: Sacrifice (2000) and Rise of Legends (2006) borrowed its “hero-centric RTS” model, while indie titles (Stellaris Nexus) echo its era-driven asymmetry. Yet Riverworld’s true successor is hypothetical: Cryo’s unrealized blueprint—had it embraced turn-based pacing (per Silva’s plea)—might have birthed a Civilization-level classic.

Conclusion

Verdict: A Noble Shipwreck

Philip José Farmer’s Riverworld is a paradox: a game radiating intellectual ambition yet sabotaged by its creators’ overreach. Cryo’s attempt to marry Farmer’s heady themes with 3D RTS dynamism produced a fascinating misfire—a world where Burton’s voyage feels tragically unmoored. For historians, it’s an essential artifact of late-’90s experimental game design; for players, a frustrating relic. Yet within its janky code lies a prototype for what might’ve been. As Silva implored: “Remake, please?” Until then, Riverworld remains a poignant tombstone to the risks of reaching beyond one’s grasp.

Final Score: ★★☆☆☆ (2/5)

A flawed artifact with sparks of genius—best appreciated as a museum piece.