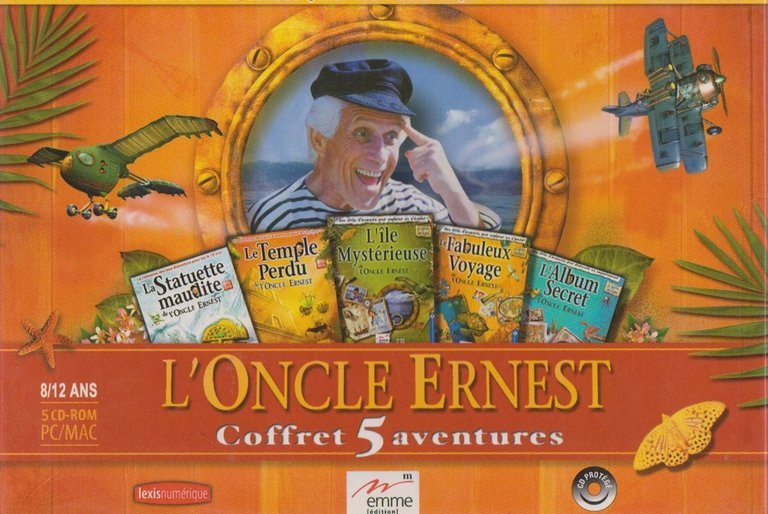

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: EMME Interactive SA, Lexis Numérique SA

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

L’Oncle Ernest: Coffret 5 aventures is a compilation of five adventure puzzle games featuring the eccentric inventor and traveler, Uncle Albert. Players explore Uncle Albert’s magical album, filled with sketches, living animals, and working mechanisms, solving puzzles to unlock new pages and uncover hidden treasures. The collection includes Uncle Albert’s Magical Album, Le Fabuleux Voyage de l’Oncle Ernest, Uncle Albert’s Mysterious Island, Le Temple Perdu de l’Oncle Ernest, and La Statuette maudite de l’Oncle Ernest, offering a rich and engaging adventure experience.

L’Oncle Ernest: Coffret 5 aventures – A Forgotten Gem of French Interactive Storytelling

Introduction

In an era dominated by 3D action titles and sprawling RPGs, L’Oncle Ernest: Coffret 5 aventures (2004) stands as a quiet revolution—a love letter to whimsy, invention, and the art of storytelling. This compilation bundles five point-and-click adventures from French studio Lexis Numérique, a series that sold over 500,000 units domestically but remains obscure beyond Francophone borders. At its core, the Uncle Ernest games redefine the adventure genre through their blend of tactile puzzle-solving, live-action cinema, and a narrative framework that feels like stepping into a child’s daydream. This review argues that the series represents a pioneering moment in European game design, merging educational charm with avant-garde presentation.

Development History & Context

A Studio Born from Storytelling

Lexis Numérique, founded in the mid-1990s, became known for narrative experimentation under director Éric Viennot. A former comic artist and filmmaker, Viennot envisioned games as interactive storybooks, drawing inspiration from silent film comedians like Chaplin and Tati. The Uncle Ernest series (1998–2004) was his magnum opus—a family-friendly saga that rejected the graphical arms race of its era.

Technological Constraints as Creativity

Developed for Windows 98 and early Mac OS systems, the games leveraged CD-ROM storage to deliver a hybrid of pre-rendered 2D art, FMV cutscenes, and simple mouse-driven interactions. While contemporary titles like Grim Fandango (1998) pushed 3D innovation, Uncle Ernest focused on evoking the warmth of a physical artifact: a journal filled with doodles, gadgets, and living creatures. The 2004 compilation, released when DVD-ROMs were standard, felt deliberately anachronistic, doubling down on the charm of its low-fi audiovisuals.

A French Gaming Renaissance

The late ’90s marked a golden age for French adventure games, with titles like Atlantis: The Lost Tales (1997) and The Cameron Files (1999) gaining traction. Uncle Ernest distinguished itself by targeting younger audiences while retaining sophistication in its puzzles and themes. Its success paved the way for Lexis’ later projects, including the noir thriller In Memoriam (2003).

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Mythos of Uncle Ernest

The series centers on the titular uncle, an eccentric globetrotter and inventor whose fantastical journal is discovered by his grand-nephew. Each game—Magical Album (1998), Fabulous Voyage (1999), Mysterious Island (2000), Lost Temple (2003), and Cursed Statuette (2004)—chronicles a self-contained adventure, from exploring desert islands to deciphering ancient curses.

Characters as Archetypes

Uncle Ernest (voiced by Patrice Baudrier) is a mischievous yet paternal figure, filmed in live-action against green-screen backdrops. His playful monologues, delivered directly to the player, evoke the tradition of oral storytelling. Secondary characters, like the tribal guide Chipikan in Lost Temple, serve as catalysts for moral dilemmas—e.g., balancing curiosity with cultural preservation.

Themes of Legacy and Discovery

Beneath its whimsical surface, the series grapples with impermanence. The journal itself is a metaphor for memory, decaying as digital “bookworms” chew through its pages. Players must restore it by solving puzzles, literally piecing together Ernest’s legacy. The narrative also critiques colonialist exploration: in Mysterious Island, Ernest’s treasure hunt disrupts an ecosystem, forcing reflection on environmental stewardship.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Album as Interface

The game’s defining innovation is its interface: a virtual book whose pages host interactive dioramas. Players manipulate objects (a magnifying glass, a wind-up toy crab) to progress, often combining items across pages. For example, photographing a hidden symbol in one chapter might reveal a clue in another.

Puzzle Design: Logic Meets Whimsy

Puzzles range from inventory-based riddles (e.g., using a magnet to retrieve a key) to rhythmic minigames (calming a hostile parrot by mimicking its song). Later entries introduce meta-challenges, like repairing a broken film projector to view crucial cutscenes. While some puzzles suffer from moon logic—Cursed Statuette’s totem assembly feels arbitrary—the focus on tactile experimentation keeps frustration low.

Progression and Replayability

Unlocking new chapters rewards players with FMV sequences that deepen Ernest’s backstory. However, the episodic structure limits branching paths, favoring linear storytelling. The compilation’s lack of gameplay enhancements (e.g., hint systems) feels like a missed opportunity for modern audiences.

World-Building, Art & Sound

A Handcrafted Aesthetic

Each album page is a collage of watercolor landscapes, CGI animals, and photographed objects, evoking a scrapbook assembled by a mad scientist. The visual chaos is grounded by a cohesive palette: ochre for desert adventures, azure for oceanic voyages.

Live-Action Surrealism

The FMV cutscenes, shot with theatrical flair, blend slapstick humor and existential musings. In Fabulous Voyage, Ernest pilots a rickety biplane through a storm, winking at the camera as lightning strikes—a moment that feels both nostalgic and eerily timeless.

Sound Design as Narrative Tool

Jean Pascal Vielfaure’s score oscillates between jaunty accordion melodies and ambient textures (e.g., creaking ship hulls, jungle rainfall). Ernest’s voiceover narration—sometimes encouraging, sometimes teasing—creates an intimate bond with the player. Notably, the French dubs retain wordplay lost in the English translations, such as puns involving “bidules” (gadgets).

Reception & Legacy

Commercial Success, Niche Recognition

The series was a hit in France, praised for its educational value and artistic ambition. However, the latter two games never saw English releases, limiting international appeal. By the mid-2000s, Lexis shifted focus to darker narratives (In Memoriam), leaving Uncle Ernest as a relic of their idealistic era.

Influence on Interactive Storytelling

The series’ legacy lies in its blurring of mediums. Games like The Stanley Parable (2013) and Journey (2012) echo its emphasis on tactile immersion and narrator-as-character. Meanwhile, indie darlings like A Juggler’s Tale (2021) owe a debt to its storybook aesthetic.

Conclusion

L’Oncle Ernest: Coffret 5 aventures is not a perfect compilation—its technical simplicity and occasional puzzle obscurities show their age. Yet as a cultural artifact, it embodies a fearless vision of games as interactive folklore. Éric Viennot’s creation proves that innovation isn’t always about polygons or open worlds; sometimes, it’s about weaving magic from paper, pixels, and pure imagination. For historians, it’s a vital footnote in the evolution of European game design. For players, it’s a portal to a time when adventure games dared to be quiet, curious, and unapologetically human.

Final Verdict: A singular, if uneven, masterpiece of narrative design—best appreciated by those willing to embrace its quirks as features, not flaws.