- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Reactor Products

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Platform, Puzzle elements

Description

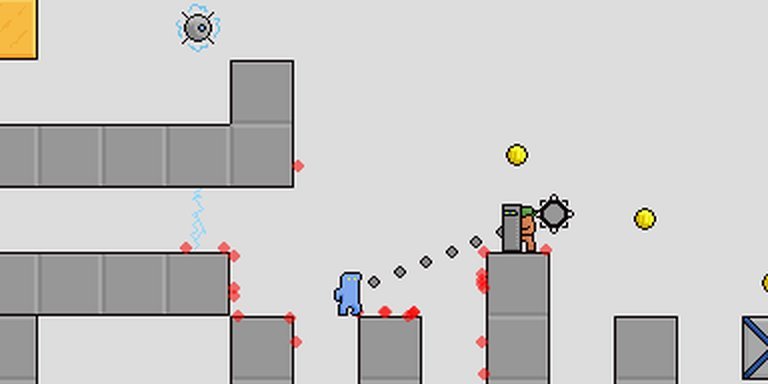

Bombing Room is a 2D side-scrolling action-platformer with puzzle elements, developed by Reactor Products and released for Windows in 2008. Players navigate dynamic environments using direct controls, employing strategic movements and problem-solving to progress. Created primarily by Arvi Teikari (credited as Hempuli), the game features nostalgic sound effects borrowed from classic titles like Metroid and RPG Maker 2000, blending platforming challenges with tactile puzzle mechanics in a retro-inspired package.

Bombing Room: A Modest Debut in the Shadow of Indie Aspirations

Introduction

In the annals of indie gaming history, Bombing Room (2008) occupies a curious niche: a humble, self-aware experiment from Finnish developer Arvi Teikari (known as Hempuli), whose later works like Environmental Station Alpha and Baba Is You would achieve far greater acclaim. Developed during a formative period of indie game exploration, Bombing Room is simultaneously a relic of 2000s DIY development and a testament to the iterative creative process. This review unpacks its legacy as a rough-hewn platformer-puzzle hybrid, examining how its technical limitations, earnest design, and unabashed inspirations laid groundwork for a developer’s evolution, even as the game itself faded into obscurity.

Development History & Context

Studio & Vision:

Bombing Room emerged from Reactor Products, a solo venture by Hempuli, then a teenager experimenting with game engines like Multimedia Fusion (later Clickteam Fusion 2.5). At a time when indie development was still nascent, tools like Fusion democratized creation but imposed constraints—limited physics, rigid 2D rendering, and rudimentary sound integration. Hempuli’s vision, per their retrospective admission, was simple: to build a “cohesive” game with a level editor, a feature that reflected their passion for player-driven creativity.

Technological Landscape:

Released in January 2008, Bombing Room arrived amid a wave of Flash-based platformers and the meteoric rise of N (Metanet Software, 2005), a minimalist precision-platformer that inspired Hempuli’s design. The game’s tech stack—Fusion’s drag-and-drop logic and borrowed sound effects from Metroid, Soldat, and RPG Maker 2000—underscored resourcefulness over polish. With no budget for original art or music, Bombing Room was a collage of influences, its development sustained by collaborative playtesting (24 credited testers, including peers like Nicklas Nygren of Knytt Stories fame).

Gaming Ecosystem:

The era prioritized accessibility over ambition. Mobile gaming was embryonic (Angry Birds debuted in 2009), and Steam’s indie marketplace wouldn’t flourish for years. Bombing Room’s release on Windows leveraged this openness, targeting a niche audience receptive to lo-fi experiments. Yet, its inspirations—Tekkyuuman’s bomb-defusing mechanics and N’s razor-edged platforming—placed it in a competitive subgenre where it struggled to stand out.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Bombing Room eschews explicit narrative, a common trait among indie platformers of its time. Instead, its thematic core emerges through abstract environmental storytelling:

– Isolation & Peril: Levels unfold in sparse, claustrophobic chambers, evoking a laboratory-like setting where the player navigates hazards (falling debris, explosives) as if part of an unseen experiment.

– User-Created Mystery: The level editor allowed players to craft their own vignettes, indirectly fostering a communal lore. However, without narrative scaffolding, these scenarios leaned on mechanical tension rather than emotional stakes.

Dialogue and characters are absent, leaving atmosphere to the interplay of lighting (minimalist gradients) and sound design—a patchwork of eerie bleeps and explosions that amplified the game’s tension-by-proxy approach. Thematically, it echoed early-2000s platformers’ fascination with emergent challenge over authored storytelling.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop:

The game blends precision platforming with puzzle-solving. Players navigate side-scrolling rooms filled with bombs, switches, and traps, manipulating environmental triggers to progress. Controls are direct but stiff—a Fusion-engine limitation—with inertia-less movement that prioritized puzzle logic over kinetic fluency.

Innovations & Flaws:

– Level Editor: A rare feat for 2008 indies, the editor empowered players to design and share stages. However, its clunky interface and lack of scripting tools limited creativity.

– Bomb Mechanics: Borrowing from Tekkyuuman, bombs served as both obstacles and tools. Players could redirect explosions to destroy barriers—a clever twist hamstrung by inconsistent physics.

– Progression & UI: No meta-progression system existed. Levels were accessed via a barebones menu, and the UI—functional but austere—lacked feedback for errors, exacerbating trial-and-error frustration.

Critical Flaws:

– Janky Collision Detection: Hitboxes often misaligned with sprites, leading to unfair deaths.

– Repetitive Soundscape: Recycled sound effects grew grating, undermining tension.

– Difficulty Spikes: Uncurated player-made levels exacerbated balance issues, alienating newcomers.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction:

Hempuli’s art—pixelated but expressive—embraced a grungy, industrial aesthetic. Walls resembled corroded metal, and bombs glowed with rudimentary menace. Though technically primitive, the art conveyed a cohesive dystopian vignette, reminiscent of Liero’s (1998) anarchic charm.

Atmosphere:

The game’s mood relied on claustrophobic level design and stark lighting. Shadows pooled in corners, and screen-shake effects amplified explosions, creating a sense of reverberating danger. Yet, without dynamic music or ambiance, the world felt static—a series of challenges, not a living space.

Sound Design:

A Frankenstein’s monster of borrowed SFX—Metroid’s sci-fi bleeps, Soldat’s gunfire—created tonal dissonance. While functional, the lack of original audio weakened immersion. The silence between explosions heightened isolation but also highlighted the game’s budgetary constraints.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception:

No critic reviews surfaced at release—unsurprising for a no-budget indie in 2008. User impressions (via MobyGames and forums) were mixed:

– Praise: Highlighted the editor’s potential and satisfying puzzle-solving.

– Criticism: Lamented janky controls and uninspired level design.

Post-Release Evolution:

Hempuli’s candid 2025 reflection—”not really all that great”—captures its reputation: a flawed but formative project. The game faded quickly, overshadowed by contemporaries like N and Spelunky (2008).

Industry Influence:

Though not directly influential, Bombing Room’s focus on user-generated content foreshadowed indie trends later perfected in Super Mario Maker (2015). For Hempuli, it was a crucial stepping stone:

– Lessons in puzzle design informed Environmental Station Alpha’s Metroidvania depth.

– Editor limitations inspired Baba Is You’s (2019) accessible yet profound systems.

Furthermore, its open-source ethos—borrowing assets, crediting testers—mirrored indie dev culture’s collaborative roots, predating platforms like itch.io.

Conclusion

Bombing Room is neither a hidden gem nor a forgotten masterpiece. It is, however, a poignant artifact of indie gaming’s adolescence—a game that prioritized earnest experimentation over polish, laying bare the messy process of creation. Its value lies not in execution but in context: a proving ground for a developer whose later works would redefine puzzle-game innovation. For historians, it’s a lens into 2000s DIY culture; for players, a curiosity best appreciated as a developmental footnote. In Hempuli’s own words: “I had a lot of fun making it, at least.” That joy—of flawed, unfiltered creation—remains Bombing Room’s most enduring legacy.

Final Verdict:

A 2.5/5—significant as a biographical marker in indie history but inaccessible to all but the most forgiving retro enthusiasts.