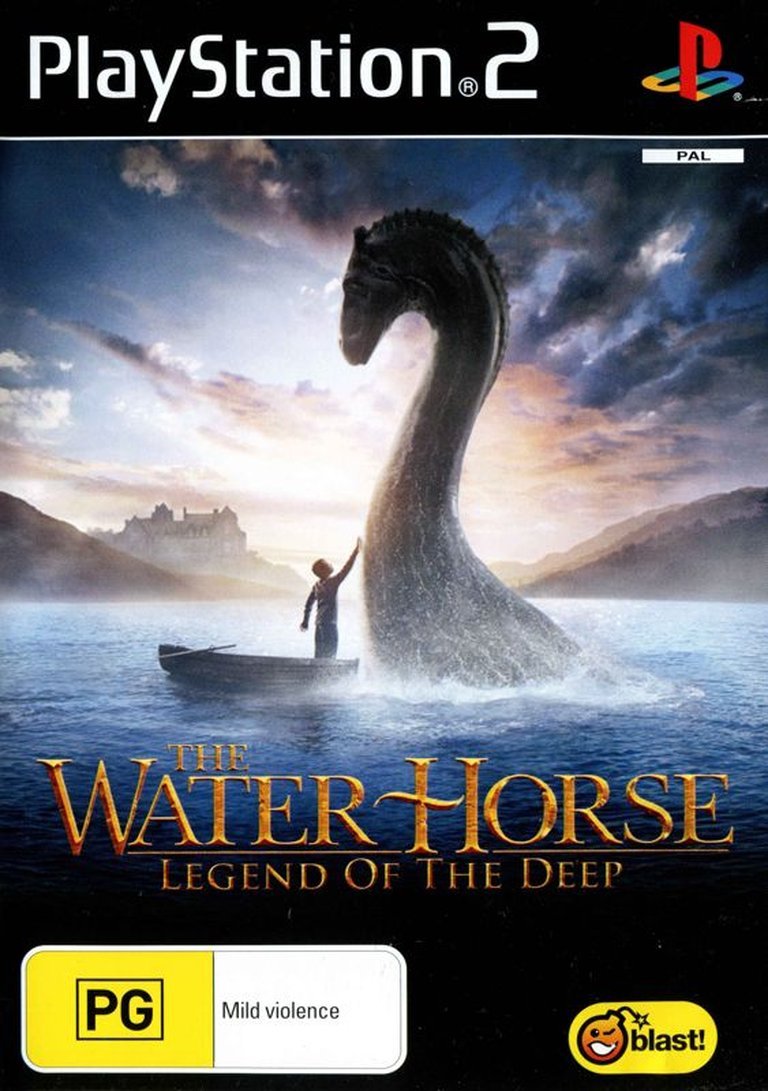

- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Nintendo DS, PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Mastertronic Group Ltd.

- Developer: Atomic Planet Entertainment Limited

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Quick Time Events, Stealth

- Setting: Fantasy, Modern

Description

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep is an action-adventure game based on the film of the same name, where players alternate between controlling Angus, a boy who discovers a mysterious egg that hatches into a mythical water horse named Crusoe, and Crusoe himself across different life stages. Set around Loch Ness, the game blends stealth segments as Angus sneaks past guards to care for his creature, with varied aquatic gameplay for Crusoe—from eating apples as a baby to navigating hazards as an adult in the open loch. Players collect mosaic pieces to unlock movie clips and replay levels in this charming adaptation of the beloved story.

Gameplay Videos

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep Free Download

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep Guides & Walkthroughs

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Perfect for fans of the movie, the novel, or anyone who dreams of befriending the legendary creature of the deep, The Water Horse offers a rich blend of stealth, puzzle-solving, and heartwarming action.

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep: Review

Introduction

Beneath the misty allure of Loch Ness lies a legendary creature and a video game adaptation that sinks more than it swims. The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep (2008), developed by Atomic Planet Entertainment and published by Mastertronic Group Ltd., attempted to translate the whimsy of Dick King-Smith’s novel and its film counterpart into an interactive experience. Released for the PlayStation 2, Windows, and Nintendo DS, the game promised a heartwarming journey of friendship between a boy and a mythical beast but drowned under the weight of technical limitations and uninspired design. This review argues that while the game’s ambition to mirror the film’s charm is palpable, its execution cements it as a forgettable relic of the late-2000s licensed-game era—a cautionary tale of how rushed adaptation can undermine narrative magic.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Licensed-Game Landscape

Atomic Planet Entertainment, best known for budget-friendly licensed titles like Thomas & Friends: A Day at the Races and Casper’s Scare School, approached The Water Horse as part of a prolific but creatively constrained portfolio. Led by CEO Sean Brennan and Executive Producer Graeme Boxall, the team faced the Sisyphean task of adapting a visually ambitious film—aided by Weta Workshop’s Oscar-nominated creature effects—into a multi-platform game amid shrinking budgets for movie tie-ins. By 2008, the PlayStation 2 was in its twilight, yet its install base made it a pragmatic target for family-friendly releases.

Technological Constraints

The game’s fragmented design—switching between bird’s-eye stealth, quick-time events, and aquatic navigation—reveals the strain of developing across three platforms with disparate capabilities. Atomic Planet’s experience with handhelds like the DS (evident in Charlotte’s Web adaptations) clashed with the demands of 3D environments on PS2 and PC. The result was a compromised vision: textures resembled “flat, low-resolution bitmaps” (Qualitipedia), animations echoed “stick puppets” (ibid.), and the FMV cutscenes felt jarringly disconnected from in-game visuals.

Era of Cynical Cash-Ins

The Water Horse arrived during a nadir for licensed games, where quick turnarounds often trumped quality. The game’s development cycle—aligned with the film’s December 2007 release—left little room for polish. Mastertronic, a publisher synonymous with budget re-releases, prioritized accessibility over depth, mirroring trends seen in contemporaries like Barnyard (2006) or Alvin and the Chipmunks (2007). This context underscores why The Water Horse emerged as a functional but soulless commodity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Characterization: A CliffNotes Retelling

The game mirrors the film’s WWII-era premise: Young Angus MacMorrow discovers a mysterious egg on Loch Ness’ shores, which hatches into Crusoe—a water horse destined to become the “monster” of legend. Play alternates between Angus’ stealth missions to care for Crusoe and direct control of the creature across four life stages. While the interstitials use film clips to advance the story (e.g., Crusoe’s growth spurs military intrigue), the narrative feels threadbare. Angus’ grief for his absent naval father—a poignant film subplot—is reduced to decorative text. Crusoe, devoid of the film’s emotive CGI subtlety, becomes a mechanical plot device.

Themes: Lost in Translation

The novel and film explored themes of wartime resilience, loss, and ecological mythmaking. The game pays lip service to these ideas—Angus’ evasion of soldiers metaphorizes protecting innocence amid conflict—but reduces them to repetitive objectives. The bond between boy and beast, central to the source material, is undermined by gameplay segregation: Angus’ stealth and Crusoe’s mini-games exist in separate vacuums, denying emotional synergy. Collectible “mosaic pieces” (unlocking movie clips) further commodify the story’s wonder into checklist busywork.

Dialogue & Pacing

Voice acting is minimal, with text boxes delivering stilted exposition (e.g., Angus’ sister Kirstie chirping, “Watch out for Mum!”). The lack of narrative urgency—despite timed missions—renders the experience inert. Crusoe’s escape to the loch, a film climax of Spielbergian stakes, becomes a tedious obstacle course devoid of catharsis.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Fragmented Identity

The Water Horse oscillates between two dissonant gameplay styles:

1. Angus’ Stealth Missions: Bird’s-eye view segments where players sneak past soldiers and family members. Mechanics include throwing stones for distractions, placing planks to cross gaps, and using “four-leap” clovers for temporary invisibility.

2. Crusoe’s Growth Stages:

– Baby: Tap buttons to catch apples in a barrel (avoiding rotten ones).

– Toddler: Quick-time events to “teach” swimming in a bathtub.

– Teenager: Pond navigation, eating fish to boost speed while avoiding lily pads.

– Adult: Loch Ness exploration, dodging mines, boats, and surfacing for air.

Innovation vs. Frustration

The switching perspectives aim for variety but falter in execution. Angus’ stealth, hobbled by rudimentary AI (guards pivot “suddenly [like] cheaply programmed scripts” per Qualitipedia), lacks tension. Crusoe’s stages, while conceptually inventive, suffer from clunky controls—particularly the adult phase’s collision-heavy swimming. The QTE toddler segment, criticized as “unforgiving” (Retro Replay), feels antithetical to the game’s family-friendly aim.

Progression & UI

A timer pressures players in stealth missions, yet progression is linear and frictionless. The UI is functional but sterile, with a mood meter for Angus (boosted by Crusoe’s tricks) adding little strategic depth. Collecting 100 mosaic pieces for movie clips is a transparent replayability ploy—unrewarding given the clips’ low resolution.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design: Aesthetic Poverty

The Water Horse’s art direction lacks cohesion. Angus’ farm, rendered in a flat, top-down perspective, resembles “a Walmart puppet display” (Qualitipedia), with textures likened to “dark blue and cold jelly” (ibid.). Crusoe’s design, while marginally charming in baby form, grows into a crudely animated beast whose movements lack the film’s fluidity. The Loch Ness environments, meant to evoke Scottish grandeur, are sparse and fog-shrouded—a likely cost-cutting measure.

Soundscape: Forgettable Ambiance

James Newton Howard’s film score is absent; instead, generic MIDI-esque tracks loop ad nauseam. Sound effects—a “splash” for Crusoe surfacing or a “thud” for thrown stones—are serviceable but lack dynamism. The omission of voice acting (outside FMV clips) further isolates players from the world.

Atmosphere vs. Reality

The game attempts whimsy but undermines itself with technical flaws. Crusoe’s barrel mini-game, set against a static backdrop, feels lifeless compared to the film’s lush cinematography. The loch’s “dangers” (mines, boats) register as mere hitboxes, not threats. This tonal dissonance—between source material magic and gameplay banality—saps the world of wonder.

Reception & Legacy

Launch & Critical Response

The Water Horse flopped commercially and critically. MobyGames records a dismal 0.7/5 average from players, citing “unforgivable level design” and “non-existent AI.” Qualitipedia’s scorching review deemed it “legendary… because of how awful [it] is.” Retro Replay offered muted praise for its “charming presentation” but lamented its “predictability.” Notably, no professional critic reviews surfaced—a testament to its obscurity.

Long-Term Influence

The game vanished into the abyss of forgotten licensed titles. Its legacy, if any, lies as a case study in mismatched ambition: Atomic Planet’s attempt to marry cinematic storytelling with variegated gameplay buckled under time constraints. While the film remains a cult favorite, the game is a footnote—a反差 to contemporaries like Chronicles of Narnia (2005), which balanced accessibility with cohesion.

Conclusion

The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep is a cautionary fable of licensed-game development—a well-intentioned but fatally compromised adaptation. Its fragmented mechanics, dated presentation, and narrative superficiality betray the source material’s heart. While younger players in 2008 might have tolerated its quirks, history judges it harshly: a rushed product emblematic of an era when “family-friendly” too often meant creatively bankrupt. For collectors, it’s a curiosity; for historians, a lesson; for gamers, a relic best left submerged in Loch Nostalgia. Two stars—a legend lost at sea.