- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Beijing Unistar Software Co., Ltd.

- Developer: Softstar Entertainment Inc.

- Genre: Role-playing, RPG

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Energy bars, Strategy, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Chinese, Fantasy

Description

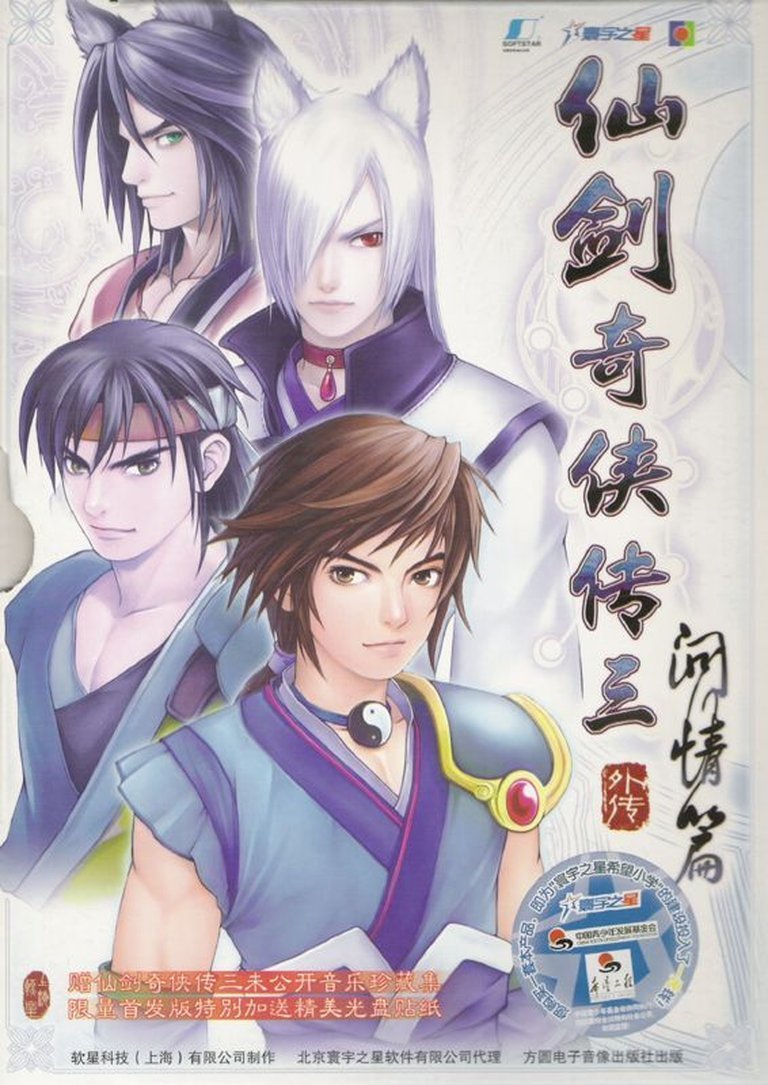

In ‘Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3 Waizhuan: Wen Qing Pian’, players follow Nangong Huang, a young disciple of the esteemed Shu mountain kung-fu school, on a mission to restore peace in China after the destruction of a sacred goddess shrine. Tasked with finding the deity Qinleng—who holds knowledge of the ‘five spiritual wheels’ (Wu Ling)—Nangong must navigate dangers using his acrobatic skills and sword magic while grappling with his inexperience in love. This standalone side-story to the third mainline game shares its 3D engine, turn-based combat system, and strategic battle mechanics, featuring visible enemies, action-speed indicators, and dual energy bars for special abilities.

Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3 Waizhuan: Wen Qing Pian: A Contemplation of Duty and Desire in a Fractured Mythos

Introduction

In the annals of Chinese role-playing game (RPG) history, few series carry the cultural weight of Xianjian Qixia Zhuan (The Legend of Sword and Fairy). Released in August 2004, Wen Qing Pian (The Proposal Chapter)—marketed as a waizhuan or “side-story” to Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3—exemplifies Softstar Entertainment’s ambition to marry wuxia romanticism with evolving technological prowess. Though dismissed by some as a narrative detour, this entry recontextualizes its predecessor’s themes of destiny and sacrifice through a lens of youthful naivety and emotional entanglement. Thesis: Wen Qing Pian stands as an essential, if flawed, artifact of early-2000s Chinese game design—a bridge between technical experimentation and the series’ signature narrative intricacy, elevated by its willingness to explore love as both weapon and vulnerability.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

Developed by Softstar’s Shanghai subsidiary and published via Beijing Unistar, Wen Qing Pian emerged during a transitional era for Chinese RPGs. The early 2000s saw domestic studios like Softstar and Kingsoft competing with Japanese giants (Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest) while navigating hardware limitations. Reusing the GameBox engine from Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3 (2003), the team prioritized iterative refinement over reinvention—leveraging fully 3D environments, rotatable cameras, and pre-rendered cutscenes. Yet, as a 2004 MobyGames entry notes, the engine’s demands strained mid-tier PCs, resulting in frame-rate inconsistencies and texture pop-in.

Cultural & Industry Landscape

At release, China’s gaming market grappled with censorship pressures and piracy, limiting Wen Qing Pian’s commercial reach. The game’s design—featuring turn-based combat and deity-driven lore—deliberately catered to fans of the xianxia genre (fantasy rooted in Taoist mythology). Its localized storytelling defied Western RPG trends, emphasizing character-driven melodrama over open-world exploration. This insularity, while a strength narratively, relegated it to niche status outside Sinophone territories.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot Structure & Characters

Set 18 years after Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3, Wen Qing Pian follows Nangong Huang, a brash Shu Mountain disciple tasked by patriarch Xu Changqing to restore equilibrium after a goddess shrine’s collapse. Accompanied by the physically formidable Wen Hui and the gluttonous, shapeshifting Five-Poison Beast Wang Pengxu, Nangong’s quest intersects with Xing Xuan—a stoic, senseless ghoul chef—and Lei Yuan-ge, a suspiciously silent revenant hunter.

The narrative’s genius lies in its refusal to reduce romance to a subplot. Each companion embodies contrasting facets of love:

– Wen Hui’s Arc: A warrior torn between filial duty (an arranged marriage) and her affection for Nangong.

– Xing Xuan’s Tragedy: His literal inability to feel warmth (a curse from infancy) contrasts with his sacrificial devotion to Wang Pengxu.

– Nangong’s Growth: His journey from arrogance to empathy mirrors wuxia tropes of “tempering the blade through hardship.”

Themes & Symbolism

The Wu Ling (“Five Spiritual Wheels”) system—a cosmological framework of elemental balance—serves as allegory for emotional equilibrium. Nangong’s mission to repair spiritual ley lines mirrors his internal struggle to reconcile love, duty, and identity. This duality peaks in the game’s three endings (a series-first branching structure):

– Wen Hui Ending: Xing Xuan dies merging with his father’s body; Wang Pengxu reverts to beast form, while Nangong wanders heartbroken.

– Wang Pengxu Ending: Xing Xuan’s temporary resurrection underscores the futility of clinging to loss.

– Perfect Ending: Unity through sacrifice; Xing Xuan accepts Wang Pengxu’s beast form, and Nangong abandons Shu Mountain’s orthodoxy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Combat & Progression

Wen Qing Pian retains Xianjian 3’s turn-based system with innovations:

– Dual Energy Bars: “Qi” fuels martial arts combos, while “Divine Power” enables elemental magic. Resource scarcity forces strategic choices.

– Speed Indicator: A timeline bar displaying turn order, allowing players to delay actions or interrupt enemy casts—a proto-Final Fantasy X “CTB” system.

– Field Techniques: Character-specific abilities (e.g., Nangong’s acrobatic leaps) solve environmental puzzles, though their implementation is rudimentary.

Character Development

Skill trees tied to elemental affinities (Fire, Water, Earth, Wind, Thunder) reward specialization. Mastering one element unlocks tiered spells, but uneven balancing (e.g., Wind’s healing dominance) limits experimentation. The “Affinity” system—where dialogue choices alter character relationships—subtly influences battle synergies but lacks Mass Effect-level consequences.

UI & Technical Nuances

Menus suffer from cluttered localization—a symptom of the rushed Chinese-to-English fan translations. The absence of quicksave magnifies dungeon frustration, while fixed camera angles obscure vital pathing cues. Still, the 3D engine enabled dynamic spell effects (e.g., Wang Pengxu’s blossom-themed attacks), a visual leap beyond sprite-based contemporaries.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design & Atmosphere

Wen Qing Pian’s rendition of Shu Mountain synthesizes Tang Dynasty architecture with xianxia’s ethereal beauty: mist-choked peaks, candlelit shrines, and bamboo forests rigged with crumbling statues. Character models, though low-poly, emote through exaggerated gestures (Wen Hui’s defiant stomps, Xing Xuan’s stoic chef poses). Cutscenes employ cinematic zooms during key revelations, heightening melodrama—a deliberate nod to wuxia cinema.

Soundtrack & Acoustics

Composer Jason Lai’s score interweaves guzheng (zither) melodies with orchestral swells, evoking both intimacy (“Whispers of the Willow”) and grandeur (“Five Elements Ascendant”). However, missing voice acting—a budgetary constraint—dampens emotional peaks, leaving dialogue reliant on text boxes. Ambient design excels in dungeons, where dripping water and distant chimes amplify isolation.

Reception & Legacy

Launch & Contemporary Reviews

Upon release, Wen Qing Pian garnered mixed responses. MobyGames’ aggregated player score (3.7/5) reflected polarization: praise for narrative ambition clashed with critiques of repetitive combat. Retro Replay later noted its “polished but uninnovative” reuse of Xianjian 3’s systems, while Chinese critics lauded its mature handling of romance—a rarity in 2004’s RPG landscape.

Long-Term Influence

The game’s legacy crystallizes in three ways:

1. Branching Endings: Inspired later Xianjian entries like Xianjian 4 (2007) to adopt multi-path storytelling.

2. Character Archetypes: Xing Xuan’s tragic nobility prefigures Genshin Impact’s Zhongli, while Wang Pengxu’s duality echoes Okami’s animalistic mysticism.

3. Cultural Preservation: As part of the 2005 compilation Junyoung Shenqing, it introduced new audiences to xianxia’s narrative potential.

Yet its obscurity remains tethered to context—no official English localization, limited physical prints, and Softstar’s subsequent bankruptcy. Today, it thrives chiefly as a fan-translated cult classic.

Conclusion

Xianjian Qixia Zhuan 3 Waizhuan: Wen Qing Pian is neither a masterpiece nor a footnote. It is a time capsule of Chinese RPG development at the dawn of 3D—a game that dared to interrogate love’s cost amid apocalyptic stakes. Its combat, while iterative, showcased tactical depth; its characters, though archetypal, resonated through vulnerability. For historians, it underscores Softstar’s role in forging a distinctly Sinic RPG identity. For players, it remains a poignant reminder that “epic” tales need not abandon intimacy. In the pantheon of Legend of Sword and Fairy, Wen Qing Pian stands as the series’ most bittersweet riddle: a side-story that, against odds, became essential.