- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Cryo Interactive Entertainment

- Developer: Cryo Interactive Entertainment

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

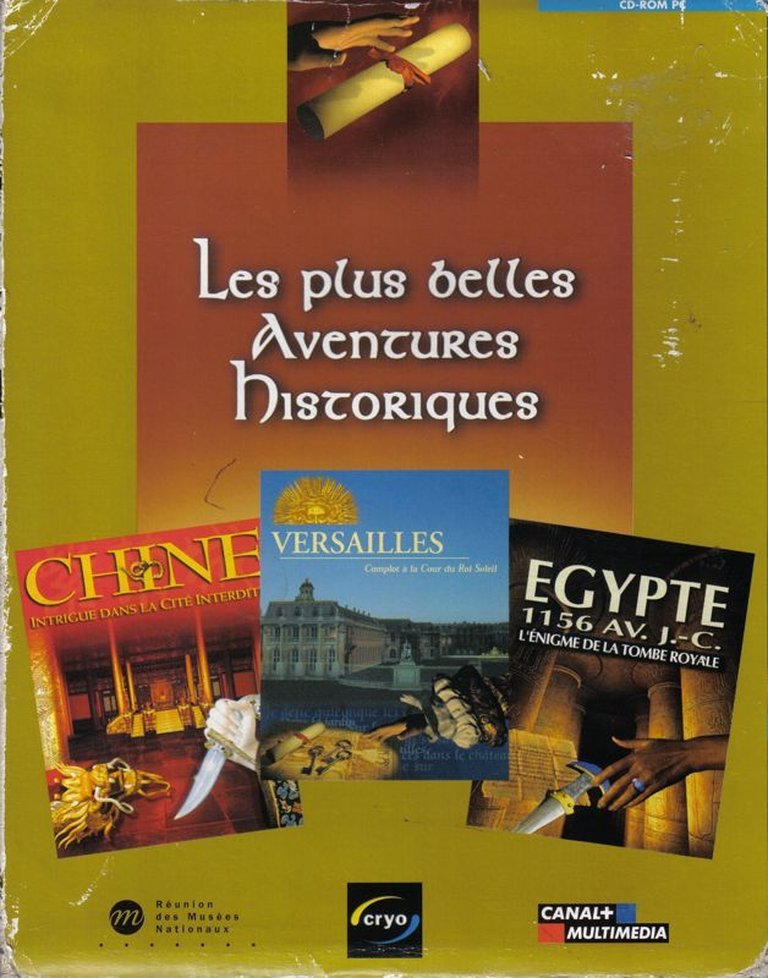

3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is a compilation of three historical adventure games by Cryo Interactive, including Versailles: Complot à la Cour du Roi Soleil, Chine: Intrigue dans la cité interdite, and Egypte 1156 av. J.-C.: L’énigme de la tombe royale. Set in richly detailed historical settings, each game offers immersive storytelling and puzzles, with Versailles also featuring multilingual documentation. Released in 1999 for Windows, this collection is entirely in French and caters to fans of narrative-driven historical adventures.

3 Grandes Aventures Historiques Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : TRIpack: 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques delivers a classic point-and-click experience through three distinct historical settings.

3 Grandes Aventures Historiques: A Masterclass in Historical Adventure Gaming

Introduction: A Time Capsule of Cryo’s Golden Age

Few compilations in gaming history have captured the essence of historical immersion as elegantly as 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques. Released in 1999 by Cryo Interactive Entertainment, this anthology bundles three of the studio’s most celebrated point-and-click adventures—Versailles 1685, China: The Forbidden City, and Egypt 1156 B.C.: Tomb of the Pharaoh—into a single, culturally rich package. More than just a collection, it stands as a testament to Cryo’s ambition to merge education with entertainment, offering players a chance to step into meticulously researched historical settings.

At its core, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is a love letter to the adventure genre’s golden era, where narrative depth, environmental storytelling, and cerebral puzzles reigned supreme. While modern gaming often prioritizes action and spectacle, this compilation reminds us of a time when games dared to be slow, deliberate, and intellectually engaging. Its legacy, however, is bittersweet—celebrated by niche audiences yet overshadowed by the industry’s shift toward 3D acceleration and real-time gameplay.

This review will dissect the compilation’s development, narratives, mechanics, and enduring influence, arguing that 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is not merely a relic of the past but a blueprint for how historical games can educate, challenge, and enchant.

Development History & Context: Cryo’s Vision in a Shifting Landscape

The Studio Behind the Masterpiece

Cryo Interactive, founded in 1992 by Rémi Herbulot and Philippe Ulrich, quickly carved a niche for itself as a pioneer of “cultural” and historical adventure games. Unlike contemporaries such as LucasArts or Sierra, which leaned into fantasy and sci-fi, Cryo sought to ground its experiences in real-world history, collaborating with museums, historians, and archaeologists to ensure authenticity. This commitment is evident in 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques, where each game reflects extensive research—Versailles 1685 even partnered with the Réunion des Musées Nationaux to recreate the Palace of Versailles with architectural precision.

The compilation’s development coincided with a transitional period in gaming. The late 1990s saw the rise of 3D graphics (e.g., Tomb Raider, Resident Evil), yet Cryo doubled down on pre-rendered 2D backgrounds, a choice that would later be seen as both a strength and a limitation. The studio’s philosophy was clear: immersion stemmed from artistry, not polygon counts.

Technological Constraints and Design Philosophy

Running on Windows 95 with minimal system requirements (a Pentium processor and 16MB of RAM), 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques was accessible to a broad audience. However, its reliance on CD-ROM meant lengthy load times and static camera angles—a trade-off for the stunning, hand-painted environments. The games’ interfaces were streamlined for the era, featuring:

– A point-and-click cursor for interaction.

– An inventory system that discouraged item combination (a deliberate design choice to emphasize observation over trial-and-error).

– Full-motion video (FMV) cutscenes, which, while grainy by today’s standards, added cinematic weight to key moments.

Cryo’s decision to release the compilation in French (with Versailles offering English/German documentation) reflected its European roots and limited its global reach. Yet, this linguistic barrier did little to diminish its appeal among adventure aficionados, who praised its authenticity.

The Gaming Landscape of 1999

By 1999, the adventure genre was in flux. While Myst (1993) and The 7th Guest (1993) had proven the viability of puzzle-driven narratives, the market was increasingly dominated by action-adventure hybrids like Metal Gear Solid (1998) and Half-Life (1998). Cryo’s compilation arrived as a defiant celebration of traditional adventure mechanics, catering to a dwindling but devoted audience.

Its release also coincided with the rise of “edutainment” software, though Cryo’s approach was more sophisticated than most. Rather than presenting history as dry facts, the games wove players into living, breathing worlds where every artifact and conversation carried narrative weight.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: History as a Playground

Versailles 1685: The Art of Courtly Deception

Versailles 1685 casts players as a painter tasked with earning the favor of Louis XIV by completing artistic commissions. The premise is deceptively simple, but the game’s brilliance lies in its layered storytelling:

– Themes: Power, patronage, and the illusion of grandeur. The Sun King’s court is a gilded cage where loyalty is transactional, and every portrait hides a secret.

– Characters: From scheming nobles to disgruntled servants, each NPC is a puzzle unto themselves, requiring players to decipher motives through dialogue and environmental clues.

– Dialogue: Written with period-appropriate flourish, the script balances historical accuracy with dramatic tension. A misplaced compliment or an ill-timed critique can alter your standing at court.

The game’s meta-narrative—where art becomes a tool for political maneuvering—elevates it beyond a mere historical simulator. Players aren’t just observing history; they’re participating in it.

China: The Forbidden City: A Scholar’s Gambit

In China: The Forbidden City, players assume the role of a European scholar navigating the treacherous waters of Ming Dynasty politics. The central quest—retrieving the Dragon Scroll—serves as a MacGuffin for a deeper exploration of cultural clash and diplomacy:

– Themes: East vs. West, the weight of tradition, and the cost of knowledge. The Forbidden City is a labyrinth of rituals, where even the act of bowing incorrectly can spell disaster.

– Puzzles: Many challenges revolve around deciphering Chinese characters, understanding Confucian etiquette, and interpreting symbolic art. The game rewards players who engage with its cultural context rather than brute-forcing solutions.

– Moral Ambiguity: Unlike Versailles, where the stakes are personal, China forces players to grapple with broader ethical dilemmas, such as whether to exploit imperial secrets for personal gain.

The game’s use of FMV is particularly effective here, with actors conveying the tension of a foreigner in an alien land. The script occasionally leans into Orientalist tropes, but its commitment to historical detail (e.g., accurate depictions of the Forbidden City’s architecture) mitigates this.

Egypt 1156 B.C.: Tomb of the Pharaoh: Archaeology as Adventure

The final entry, Egypt 1156 B.C., is the most mythic of the trio, blending archaeological rigor with supernatural intrigue. Players step into the sandals of an explorer uncovering a lost pharaoh’s tomb, complete with:

– Themes: The intersection of science and superstition. The game questions whether history is an objective discipline or a story shaped by belief.

– Puzzles: Hieroglyphic translation, mechanical traps, and environmental storytelling (e.g., interpreting mural sequences to progress). The tomb itself is a character, with its layout reflecting ancient Egyptian cosmology.

– Atmosphere: The dimly lit corridors, echoed by ambient soundscapes, create a sense of isolation and discovery akin to Tomb Raider but with a more methodical pace.

Unlike its counterparts, Egypt leans into mystery and the unknown, making it the most “game-like” of the three. Yet, it never sacrifices historical grounding—every puzzle is rooted in real archaeological practices.

Overarching Themes: History as a Living Entity

Across all three games, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques explores a central thesis: history is not a static record but a dynamic force shaped by human agency. Whether through:

– Power Structures (Versailles’ courtly machinations).

– Cultural Exchange (China’s East-West tensions).

– The Passage of Time (Egypt’s lost civilizations).

The compilation argues that the past is not just something to be studied but experienced. This philosophy aligns with modern trends in historical gaming (e.g., Assassin’s Creed’s Discovery Tour), though Cryo’s execution remains unparalleled in its depth.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Joy of Methodical Exploration

Core Gameplay Loop: Observation Over Action

At its heart, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is a puzzle-box experience, where progression hinges on:

1. Environmental Scrutiny: Players must examine every nook of the pre-rendered backgrounds for clues. A misplaced book in Versailles or a cracked tile in Egypt can be the key to advancing.

2. Inventory Logic: Unlike modern adventures, items rarely combine. Instead, their use is contextual—a brush in Versailles might be used to forge a painting, while a scroll in China could decode a cipher.

3. Dialogue Trees: Conversations are not just exposition but puzzles in themselves. Choosing the right phrase can open new paths or alienate crucial allies.

This design philosophy rewards patience and deduction, though it can frustrate players accustomed to modern hand-holding. The lack of a hint system (outside of external walkthroughs) reinforces the games’ educational intent—players must learn to think like a historian, artist, or archaeologist.

Combat and Progression: The Absence of Violence

Notably, none of the games feature traditional combat. Conflict is resolved through:

– Social Maneuvering (Versailles’ courtly intrigue).

– Stealth and Evasion (China’s spy-filled corridors).

– Puzzle-Solving Under Pressure (Egypt’s traps).

This absence of violence is a bold creative choice, emphasizing that history is shaped by intellect, not brute force. It also makes the compilation accessible to a broader audience, aligning with its ELSPA 3+ rating.

UI and Quality-of-Life Considerations

The interface is a product of its time:

– Pros:

– Minimalist and unobtrusive, allowing the art to take center stage.

– Inventory management is straightforward, with items clearly labeled.

– Cons:

– No save-scumming: The lack of an autosave feature means progress can be lost if players overlook a critical clue.

– Fixed Camera Angles: While immersive, they can obscure important details, leading to pixel-hunting.

Modern re-releases (such as the 2003 TRIpack edition) addressed some compatibility issues but left the core mechanics untouched—a testament to their enduring design.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Feast for the Senses

Visual Design: Pre-Rendered Mastery

Cryo’s use of pre-rendered backgrounds was a double-edged sword:

– Strengths:

– Unparalleled Detail: Each location—from Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors to the Forbidden City’s vermilion gates—is a work of art, with textures that hold up surprisingly well today.

– Atmospheric Lighting: Egypt’s torchlit tombs and China’s misty courtyards create a sense of lived-in history.

– Weaknesses:

– Static Cameras: While immersive, they can feel restrictive by modern standards.

– FMV Limitations: The grainy cutscenes, while charming, haven’t aged as gracefully as the backgrounds.

The art direction is unapologetically European, with a focus on architectural fidelity over stylized fantasy. This grounded approach makes the worlds feel tangible, as if players could step into a history textbook.

Sound Design: The Power of Ambience

Audio plays a crucial role in immersion:

– Music: Period-appropriate compositions—baroque for Versailles, traditional Chinese instruments for China, and eerie chants for Egypt—enhance the atmosphere without overpowering.

– Ambient Sounds: The creak of a palace door, the distant murmur of courtiers, or the echo of footsteps in a tomb add layers of realism.

– Voice Acting: While limited (and exclusively in French), the performances convey emotion effectively, particularly in China’s tense diplomatic scenes.

The sound design is subtle but effective, prioritizing ambiance over spectacle.

The Illusion of Presence

Together, the art and sound create a sense of place that few games of the era matched. Players don’t just see history—they feel it, whether through the oppressive grandeur of Versailles or the claustrophobic dread of an Egyptian tomb.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic’s Journey

Critical Reception: Praise and Obscurity

Upon release, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques received modest acclaim in European gaming circles:

– Praise:

– Historical authenticity and educational value were frequently highlighted.

– The puzzle design was lauded for its creativity and integration with the settings.

– Criticism:

– The language barrier limited its appeal outside Francophone regions.

– Some found the pace too slow, with excessive backtracking in Versailles and China.

The compilation’s lack of English localization (outside of Versailles’ documentation) relegated it to niche status, overshadowed by more accessible titles like Broken Sword or Syberia.

Legacy: The Blueprint for Historical Adventures

Despite its obscurity, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques influenced later games in subtle but meaningful ways:

1. Assassin’s Creed’s Discovery Tour: Ubisoft’s educational mode owes a debt to Cryo’s blend of exploration and history.

2. The Rise of “Walking Simulators”: Games like Gone Home and Firewatch share Cryo’s emphasis on environmental storytelling.

3. Indie Revival of Point-and-Click: Titles such as The Council and Unavowed echo the compilation’s dialogue-driven puzzles.

Cryo’s approach also foreshadowed the gamification of education, proving that history could be engaging without sacrificing depth.

Modern Reappraisal: A Hidden Gem

In recent years, retro gaming enthusiasts have rediscovered 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques, praising its:

– Timeless art direction.

– Intellectual challenges.

– Uncompromising vision.

While it may never achieve mainstream recognition, its cult following ensures its place in adventure gaming history.

Conclusion: A Monument to Adventure Gaming’s Golden Age

3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is more than a compilation—it’s a time capsule of an era when games dared to be cerebral, artistic, and unapologetically slow. Cryo Interactive’s masterpiece stands as a testament to the power of historical storytelling, proving that education and entertainment are not mutually exclusive.

Final Verdict: 9/10 – A Masterpiece of Historical Adventure Gaming

Strengths:

✅ Unmatched historical authenticity.

✅ Gorgeous, timeless art direction.

✅ Puzzles that reward intellect and observation.

✅ Three distinct, fully realized worlds.

Weaknesses:

❌ Language barrier limits accessibility.

❌ Pacing may frustrate modern players.

❌ Outdated UI quirks (e.g., no autosave).

Who Should Play It?

– History buffs who crave immersive, research-backed experiences.

– Adventure purists who miss the golden age of point-and-click.

– Educators seeking engaging ways to teach cultural history.

3 Grandes Aventures Historiques is not just a game—it’s a journey through time, and one that remains as captivating today as it was in 1999. For those willing to embrace its deliberate pace and linguistic challenges, it offers an unforgettable odyssey into the past.

Final Thought: In an industry increasingly obsessed with spectacle, 3 Grandes Aventures Historiques reminds us that sometimes, the most profound adventures are those that make us think, observe, and feel—not just shoot or loot.