- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: DOS, Palm OS, Windows

- Developer: Aragon Ltd.

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Cellular automata, Simulation

- Average Score: 68/100

Description

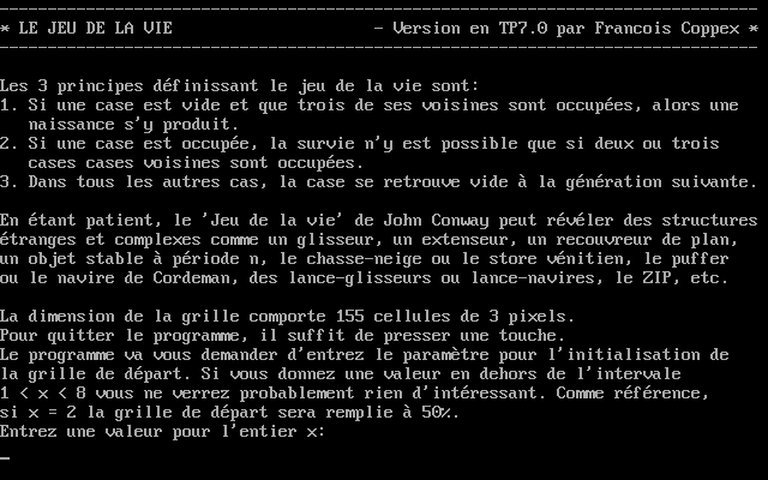

Conway’s Game of Life is a zero-player cellular automaton devised by mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. The game simulates the life cycles of single-celled entities on a 2D grid, where their survival, death, or reproduction depends on the number of adjacent neighbors. Players set initial conditions by placing cells on the grid, then observe as the system evolves autonomously through generations, creating dynamic patterns like oscillators, gliders, and stable ‘still lifes.’ Originally played manually on grid paper, the game has since been adapted to computers, allowing for complex simulations and research into emergent behaviors.

Gameplay Videos

Conway’s Game of Life Free Download

Conway’s Game of Life Mods

Conway’s Game of Life Guides & Walkthroughs

Conway’s Game of Life Reviews & Reception

sonatano1.wordpress.com : A review of Conway’s Game of Life | Everything is bad for you

classicreload.com : Conway’s Game of Life – additional information

retro-replay.com : Step into the role of a Newtonian clockmaker god with Conway’s Game of Life, the ultimate software toy that transforms your screen into a living, breathing microcosm.

mobygames.com (68/100): Average score: 3.4 out of 5

Conway’s Game of Life: A Timeless Exploration of Emergent Complexity

Introduction

Conway’s Game of Life is not merely a game—it is a profound simulation of emergence, a mathematical playground where simple rules birth unfathomable complexity. Since its inception in 1970, this cellular automaton has captivated mathematicians, programmers, and philosophers alike, serving as a testament to how rudimentary interactions can spawn intricate, self-sustaining systems. Unlike traditional games, Life has no objectives, no winners or losers—only the mesmerizing dance of cells evolving according to a few elegant rules. This review delves into the game’s development, its mechanical brilliance, its cultural impact, and its enduring legacy as a cornerstone of computational theory and artificial life.

Development History & Context

The Birth of a Mathematical Marvel

Conway’s Game of Life was conceived by British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970, but its roots trace back to the 1940s with the work of John von Neumann and Stanisław Ulam, who explored the concept of a “universal constructor”—a self-replicating machine governed by discrete rules. Conway sought to simplify these ideas, aiming to create a system that was both unpredictable and capable of infinite growth. His breakthrough came in the form of a two-dimensional grid where cells lived, died, or reproduced based on their neighbors, a ruleset so elegant it could be computed by hand on graph paper or a Go board.

The game’s public debut in Martin Gardner’s October 1970 Scientific American column catapulted it into the spotlight. Gardner framed Life as a “simulation game,” drawing parallels to biological and societal dynamics. The timing was fortuitous: the rise of accessible computing allowed researchers to simulate Life for hours, uncovering patterns like the Gosper glider gun—a configuration that spawns an endless stream of “gliders,” proving the game’s capacity for infinite growth. This discovery earned a $50 prize (equivalent to $400 today) for the MIT team that solved Conway’s challenge.

Technological Constraints and Early Implementations

Early simulations were painstakingly manual, but the 1970s saw the first digital implementations. M. J. T. Guy and S. R. Bourne wrote the inaugural interactive program in ALGOL 68C for the PDP-7, while Ed Hall’s 1976 color version for Cromemco microcomputers graced the cover of Byte magazine, reigniting interest in the game. The 1980s brought further innovation, with Malcolm Banthorpe’s BBC BASIC versions and Susan Stepney’s one-dimensional “Life on the Line.”

The game’s simplicity belied its computational depth. As hardware advanced, so did the algorithms. Early programs used two-dimensional arrays to track cell states, but optimizations like Hashlife (developed by Bill Gosper) enabled simulations of vast patterns across millions of generations. The shift from array-based to coordinate-list representations allowed for unbounded growth, though at the cost of slower neighbor-counting.

The Gaming Landscape of the Era

Conway’s Game of Life emerged alongside other “software toys” like Little Computer People and Will Wright’s Sim franchise, which also simulated emergent behaviors. However, Life stood apart as a zero-player game—a system where the player’s role was limited to setting initial conditions. This minimalist design made it a favorite among programmers, who treated it as a puzzle to optimize or a canvas for artistic expression. By the 1990s, Life had transcended its academic origins, inspiring everything from Google Easter eggs to MIDI music sequencers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The “Plot” of a Zero-Player Game

Conway’s Game of Life lacks a traditional narrative, but its emergent storytelling is unparalleled. Each simulation begins with a “seed”—a user-defined arrangement of live cells—and unfolds as a Newtonian clockwork universe, where the player acts as a detached observer. The drama lies in the patterns that emerge:

- Still Lifes: Stable configurations like the Block or Beehive, which remain unchanged.

- Oscillators: Periodic structures like the Blinker (period 2) or Pulsar (period 3), which cycle through states.

- Spaceships: Mobile patterns like the Glider, which traverse the grid.

- Methuselahs: Long-lived configurations like the R-pentomino, which take thousands of generations to stabilize.

- Guns and Breeders: Complex machines like the Gosper glider gun, which generate infinite streams of spaceships.

The game’s themes are deeply philosophical:

– Emergence and Self-Organization: Life demonstrates how simple rules can produce complex, ordered structures without a central designer.

– Determinism vs. Unpredictability: Despite its deterministic rules, Life’s long-term behavior is often chaotic and unpredictable, mirroring real-world systems.

– Computational Universality: Life is Turing-complete, meaning it can simulate any algorithm given enough cells and time. This has led to the construction of logic gates, counters, and even a working Tetris clone within its grid.

– Existential Metaphors: Philosophers like Daniel Dennett have used Life to explore concepts of consciousness, free will, and evolution, arguing that complex phenomena can arise from simple, deterministic laws.

The Language of Patterns

While Life has no dialogue, its “characters” are its patterns, each with a taxonomy and lore:

– Gliders: The simplest spaceships, moving diagonally at c/4 (the “speed of light” in Life).

– Lightweight/Middleweight/Heavyweight Spaceships: Faster or more complex mobile patterns.

– Gemini and Knightships: Oblique spaceships discovered decades after Life’s inception, proving that even a 50-year-old system can yield new surprises.

– Universal Constructors: Hypothetical patterns capable of building copies of themselves, realizing von Neumann’s original vision.

The LifeWiki and Catagolue databases serve as encyclopedias of these patterns, documenting discoveries like the 0E0P metacell, a self-replicating structure that removes itself when inactive, leaving true empty space.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Rules: Simplicity as a Virtue

Conway’s Game of Life operates on a binary, two-dimensional grid where each cell interacts with its eight neighbors (Moore neighborhood). The rules are deceptively simple:

- Underpopulation: A live cell with fewer than 2 neighbors dies.

- Survival: A live cell with 2 or 3 neighbors lives on.

- Overpopulation: A live cell with more than 3 neighbors dies.

- Reproduction: A dead cell with exactly 3 neighbors becomes alive.

These rules are applied simultaneously to all cells in each generation, creating a discrete, deterministic evolution. The genius lies in the balance: too few neighbors lead to extinction, too many to chaos, and just the right number to stability or growth.

Gameplay Loop: The Player as a Clockmaker God

The gameplay loop is minimalist yet profound:

1. Initialization: The player places live cells on the grid (the “seed”).

2. Simulation: The system evolves autonomously, with no further input.

3. Observation: The player watches as patterns emerge, stabilize, or collapse.

There is no “win condition,” but players often seek:

– Stable or periodic patterns (e.g., still lifes, oscillators).

– Infinite growth (e.g., glider guns, breeders).

– Self-replication (e.g., the 0E0P metacell).

– Computational constructs (e.g., logic gates, Turing machines).

Innovative Systems: Beyond the Basics

While the core rules are fixed, variations and extensions have expanded Life’s possibilities:

– Life-Like Cellular Automata: Rulesets like Highlife (B36/S23) or Seeds (B2/S) modify the birth/survival conditions.

– Different Geometries: Hexagonal grids, toroidal (wrapped) universes, or even aperiodic tilings.

– Multi-State Cells: Variations like Immigration or QuadLife introduce additional cell states.

– Asynchronous Updates: Algorithms that emulate synchronous behavior without strict simultaneity.

Flaws and Limitations

Despite its elegance, Life has constraints:

– Edge Effects: Finite grids require boundary conditions (e.g., toroidal wrapping or “dead” edges).

– Computational Limits: Large patterns demand optimized algorithms (e.g., Hashlife) to simulate efficiently.

– Pattern Collisions: Unintended interactions can disrupt carefully constructed machines.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Infinite Grid: A Canvas of Possibility

Life’s “world” is an infinite, abstract Cartesian plane, devoid of traditional aesthetics but rich in mathematical beauty. The visual experience is defined by:

– Symmetry and Chaos: Random seeds often evolve into symmetric still lifes or chaotic “soup.”

– Dynamic Motion: Gliders and spaceships create a sense of movement, while oscillators pulse rhythmically.

– Color and Texture: Modern implementations (e.g., Golly) use color to highlight different cell states or generations, adding depth to the monochrome original.

Sound Design: From Silence to Symphony

Life is inherently silent, but its patterns have inspired sonic interpretations:

– MIDI Sequencers: Programs like glitchDS or Runxt Life translate cell states into musical notes.

– Generative Music: The game’s emergent behavior has been used to create procedural soundscapes, with oscillators driving rhythms and gliders triggering melodies.

Atmosphere: Meditative and Hypnotic

The game’s pacing is described as “Meditative / Zen”—a slow, methodical unfolding of patterns that rewards patience. The lack of direct interaction fosters a contemplative mood, where the player becomes a passive observer of a self-contained universe. This aligns with its classification as a “software toy” rather than a traditional game.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception

Conway’s Game of Life was never a commercial product, but its academic and cultural impact has been monumental:

– Scientific American (1970): Gardner’s column sparked widespread fascination, particularly among mathematicians and computer scientists.

– Cult Following: By the 1970s, Life had a dedicated community of researchers who competed to discover new patterns (e.g., the first glider gun).

– Modern Recognition: While it lacks a MobyGames score (rated 3.4/5 by players), its influence is measured in citations, implementations, and homages rather than sales.

Evolution of Its Reputation

Initially seen as a mathematical curiosity, Life’s reputation has grown to encompass:

– Computational Theory: Proof of its Turing-completeness (1980s) elevated it to a model of universal computation.

– Artificial Life: Life is a foundational example of emergent behavior, influencing fields like swarm robotics and evolutionary algorithms.

– Philosophy: Dennett and others have used Life to argue for bottom-up explanations of complexity, challenging top-down design paradigms.

Influence on Subsequent Games and Media

Life’s DNA is embedded in numerous works:

– Games:

– Dr. Blob’s Organism (1992): A shoot-’em-up where Life patterns form amoeba-like enemies.

– The Sims (2000): Will Wright cited Life as an inspiration for emergent gameplay.

– No Man’s Sky (2016): Uses procedural generation techniques akin to Life’s rules.

– Software:

– Golly, Mirek’s Cellebration, and Xlife: Modern simulators with advanced features.

– Google’s Easter Egg: Typing “Conway’s Game of Life” into Google Search launches an interactive simulation.

– Literature and Film:

– David Brin’s Glory Season (1993) features a competitive version of Life.

– Piers Anthony’s Of Man and Manta trilogy includes a Life-based alien lifeform.

The Life Community Today

The game’s legacy lives on through:

– LifeWiki: A comprehensive wiki documenting patterns, rules, and discoveries.

– ConwayLife.com Forums: A hub for enthusiasts to share new findings (e.g., the 2018 discovery of the elementary knightship).

– Catagolue: A database cataloging objects in Life and similar automata.

– Annual Challenges: Events like the Gemini Challenge push the boundaries of pattern discovery.

Conclusion: A Game That Transcends Gaming

Conway’s Game of Life is a masterpiece of minimalist design, proving that complexity need not arise from intricate mechanics but from the interplay of simple rules. It is a game without players, a universe without a creator, and a computer without hardware. Its legacy is not measured in sales or critical scores but in its profound influence on science, art, and philosophy.

Final Verdict: ★★★★★ (5/5) – A Timeless Classic

Strengths:

– Elegant, accessible rules that yield infinite depth.

– Profound themes of emergence, computation, and determinism.

– Enduring community and ongoing discoveries (e.g., new spaceships in 2018).

– Cross-disciplinary impact, bridging mathematics, computer science, and philosophy.

Weaknesses:

– Not a “game” in the traditional sense—lacks goals, interaction, or narrative.

– Steep learning curve for advanced pattern construction.

– Computationally intensive for large-scale simulations.

Place in History:

Conway’s Game of Life is more than a game—it is a cultural artifact, a scientific tool, and a philosophical metaphor. It stands alongside Tetris and The Sims as a title that redefines what games can be: not just entertainment, but windows into the nature of complexity itself. For anyone interested in emergence, computation, or the beauty of mathematical systems, Life remains an essential experience.

“Life is a game that plays itself—a mirror to the universe’s own emergent dance.”