- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Leonard Richardson

- Developer: Leonard Richardson

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Boons and punishments, Divine intervention, Randomly-generated dungeons

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 50/100

Description

In ‘What Fools These Mortals’, players assume the role of a deity overseeing mortal adventurers in a randomly-generated dungeon inspired by NetHack. As a passive god, you influence your champions by granting boons or punishments in response to their sacrifices and prayers, rather than directly controlling their actions. The goal is to guide your chosen adventurer to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor and sacrifice it to you, though their success is never guaranteed—mortals may quit, fail, or perish despite your divine intervention.

What Fools These Mortals Free Download

What Fools These Mortals Guides & Walkthroughs

What Fools These Mortals Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (46/100): A variety of punishments to inflict on mortals.

crummy.com : I love this game!

retro-replay.com : Overall, the gameplay balances the tension of god-sim strategy with the random unpredictability of a roguelike.

vgtimes.com (55/100): What Fools These Mortals is a simulator with a fantasy twist.

What Fools These Mortals Cheats & Codes

PC

Start the game with the indicated command line parameter to activate the cheat function.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| -a[alignment letter] | Pre-selected alignment |

| -p[class letter] | Skip class selection |

| -d | Follower cannot die but game does not end |

What Fools These Mortals: A Divine Roguelike Experiment

Introduction

In the pantheon of roguelike games, What Fools These Mortals (WFTM) stands as a curious and often overlooked experiment—a game that dares to ask: what if you weren’t the hero, but the god watching over them? Released in 2003 by Leonard Richardson, this Python-based title is a meta-commentary on the roguelike genre itself, particularly NetHack, the game it both parodies and pays homage to. With its minimalist design, Shakespearean wit, and subversive take on player agency, WFTM is a game that challenges conventions while embracing the chaotic, often cruel nature of its inspiration.

This review will dissect WFTM in exhaustive detail, exploring its development, mechanics, narrative themes, and legacy. We’ll examine how it recontextualizes the roguelike experience, why its reception was lukewarm, and why it remains a fascinating artifact of early 2000s indie game design.

Development History & Context

The Creator and His Vision

Leonard Richardson, the sole developer behind What Fools These Mortals, was already a notable figure in the NetHack community before WFTM’s release. His work on the game was deeply personal—a love letter to the roguelike genre, but also a playful critique of its often punishing design. Richardson’s vision was clear: to invert the power dynamic of traditional roguelikes. Instead of controlling a mortal hero, players would assume the role of a capricious deity, observing and occasionally intervening in the fate of their champion.

The game’s title, lifted from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, sets the tone: it’s a story about the folly of mortals, but also the folly of gods who believe they can control fate. Richardson’s humor and literary references permeate the game, making it as much a piece of interactive satire as it is a game.

Technological Constraints and Design Choices

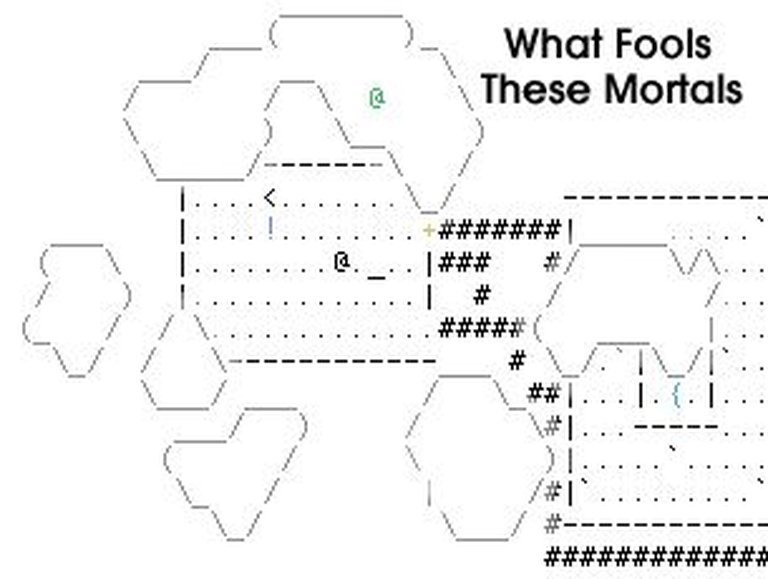

WFTM was built in Python, a choice that reflected both Richardson’s programming preferences and the game’s minimalist ambitions. The interface is a text-based, ASCII-driven affair, reminiscent of early roguelikes like Rogue or Moria. There are no fancy graphics, no animations beyond simple color changes, and no sound design to speak of. This was not a limitation but a deliberate aesthetic choice—one that reinforced the game’s focus on emergent storytelling and player imagination.

The game’s engine is a simplified version of NetHack’s mechanics, with procedurally generated dungeons, random encounters, and permadeath. However, unlike NetHack, where the player directly controls their character, WFTM abstracts most of the action. Your champion moves and fights automatically, leaving you to react to their prayers, sacrifices, and occasional moments of desperation.

The Gaming Landscape in 2003

2003 was a transitional year for gaming. The indie scene was still in its infancy, with titles like Cave Story and Dwarf Fortress just beginning to gain traction. Roguelikes, while beloved by a niche audience, were not yet the mainstream darlings they would become in the 2010s. NetHack was the undisputed king of the genre, but its complexity and punishing difficulty kept it from wider appeal.

WFTM arrived in this landscape as an oddity—a game that required players to already be familiar with NetHack to fully appreciate its humor and mechanics. It was freeware, distributed online, and lacked the polish or marketing to attract a broad audience. Yet, for those who discovered it, WFTM offered something unique: a chance to experience the roguelike from the other side of the altar.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Premise: A God’s-Eye View

WFTM’s narrative is deceptively simple. You are a god, and your mortal champion is attempting to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor—the same MacGuffin from NetHack—from the depths of a procedurally generated dungeon. Your role is not to guide them directly but to respond to their actions. Will you accept their sacrifices and grant them boons? Will you smite them for their hubris? Or will you ignore their prayers and let fate decide their outcome?

The game’s brilliance lies in its subversion of expectations. In most roguelikes, the player is the underdog, fighting against overwhelming odds. In WFTM, you are the overseer, but your power is limited. Your champion is an autonomous entity with their own agenda, and they may abandon their quest out of boredom or frustration. This creates a fascinating tension: you are both omnipotent and powerless, a god who must rely on the whims of a mortal.

Themes: Folly, Fate, and Free Will

-

The Folly of Mortals (and Gods)

The game’s title is not just a literary reference but a central theme. Your champion is a fool, blindly stumbling through dungeons, making poor decisions, and often dying in ridiculous ways. But you, the player, are also a fool—believing that your interventions can meaningfully alter their fate. The game’s changelog even jokes: “Almost none of the excitement of real NetHack!”—a meta-commentary on how your divine meddling often amounts to little. -

The Illusion of Control

WFTM is a game about the illusion of control. You can bless your champion, smite their enemies, or ignore their pleas, but ultimately, their fate is determined by the game’s RNG. This mirrors the roguelike experience itself, where players often blame “bad luck” for their failures. Here, you are the one dispensing that luck, but you are just as subject to its whims. -

Shakespearean Mischief

The game’s tone is one of playful mischief, much like Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Your champion’s struggles are framed as a cosmic joke, and your role is that of the trickster god. The in-game messages are filled with dry humor, such as:- “Your champion has died. Would you like to try again?”

- “Your champion has grown bored and quit. Perhaps they had better things to do.”

These messages reinforce the game’s central idea: that the struggle is absurd, and the only meaningful choice is how you react to it.

Characters and Dialogue

WFTM has no traditional characters or dialogue. Instead, the “characters” are the abstract forces at play:

– The Champion: A faceless, nameless adventurer whose only defining trait is their stubbornness (or lack thereof).

– The Player-God: You, the omniscient but impotent overseer.

– The Dungeon: A procedurally generated labyrinth filled with traps, monsters, and treasures, all designed to thwart your champion’s progress.

The “dialogue” consists of event logs and system messages, which are often humorous or sarcastic. For example:

– “Your champion has found a potion. They drink it. It was poison. They die.”

– “Your champion prays for help. You ignore them. They die.”

These messages are the game’s way of winking at the player, acknowledging the absurdity of the roguelike genre while embracing it.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop

WFTM’s gameplay is stripped down to its essence:

1. The Champion’s Journey: Your champion automatically explores the dungeon, fighting monsters, collecting items, and occasionally praying or sacrificing at altars.

2. Divine Intervention: At key moments, you can choose to:

– Accept a Sacrifice: Grant a boon (e.g., healing, strength, or a magical item).

– Reject a Sacrifice: Smite the champion for their insolence.

– Answer a Prayer: Provide aid when the champion is in dire straits.

– Ignore: Let fate take its course.

3. Outcomes: The champion either retrieves the Amulet of Yendor (victory), dies (defeat), or quits out of boredom (defeat).

The loop is simple, but the emergent storytelling makes each playthrough unique. Will your champion be a devout follower, constantly praying for aid? Or will they be a reckless fool, charging into battle without a second thought?

Combat and Progression

Combat in WFTM is entirely automated. Your champion fights monsters based on their stats and equipment, with no input from you. This can be frustrating—watch your champion die to a lowly goblin because they refused to retreat—but it’s also part of the game’s charm. You are not a general commanding troops; you are a spectator, occasionally tossing a bone to your champion.

Progression is tied to the champion’s success. The farther they get, the more altars they find, and the more opportunities you have to intervene. However, there is no permanent progression. Each run is self-contained, reinforcing the roguelike ethos of “try, fail, learn, repeat.”

UI and Accessibility

The UI is sparse but functional. The screen is divided into several sections:

– Event Log: A running commentary of the champion’s actions.

– Minimap: A small, ASCII-based map of the immediate surroundings.

– Status Bars: Health, mana, and other stats.

– Altar Menu: Options for responding to sacrifices or prayers.

The lack of modern UI conveniences (e.g., tooltips, detailed item descriptions) can make the game feel dated, but it’s intentional. WFTM is designed to be played by those already familiar with NetHack’s conventions.

Innovative (and Flawed) Systems

-

Automated Champion AI

The champion’s AI is simple but effective. They explore dungeons methodically, fight when necessary, and retreat when overwhelmed. However, their decision-making can be baffling. They might ignore a healing potion in favor of a cursed sword, or charge into a room full of monsters despite being at low health. This unpredictability is both a strength and a weakness—it creates emergent stories but can also feel unfair. -

Divine Intervention Mechanics

The game’s most innovative feature is its divine intervention system. You are not all-powerful; your interventions have consequences. For example:- Blessing a Champion Too Early: They may grow overconfident and die to a stronger monster.

- Smiting a Champion: They may abandon their quest out of spite.

- Ignoring Prayers: They may lose faith and stop praying altogether.

This creates a delicate balance. Do you reward devotion or punish weakness? There is no “right” answer, only consequences.

-

The Boredom Mechanic

One of WFTM’s most unique (and controversial) features is the champion’s ability to quit out of boredom. If they wander too long without progress, they may simply give up and end the run. This is a direct critique of roguelikes, where players often abandon runs out of frustration. Here, the game acknowledges that frustration and turns it into a mechanic.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting and Atmosphere

WFTM’s world is a pastiche of NetHack’s dungeons, filled with gnomish mines, undead crypts, and eldritch horrors. The setting is deliberately vague, allowing players to fill in the gaps with their imagination. The ASCII graphics and minimalist design reinforce this abstraction—you are not meant to see the dungeon as a physical space but as a stage for your champion’s struggles.

The atmosphere is one of detached amusement. You are a god, after all, and the fate of one mortal is barely a blip on your cosmic radar. The game’s humor and sarcasm prevent it from taking itself too seriously, even as it explores themes of fate and free will.

Visual Design

The visuals are intentionally retro, using ASCII characters and a limited color palette. Monsters are represented by symbols (e.g., “k” for kobolds, “D” for dragons), and items are denoted by simple glyphs. This design choice is polarizing—some players will find it charmingly nostalgic, while others will dismiss it as outdated.

However, the minimalist approach has its advantages:

– Clarity: The lack of visual noise makes it easy to parse the dungeon layout and your champion’s status.

– Imagination: The abstract visuals encourage players to fill in the details, much like reading a book.

– Performance: The game runs smoothly on even the most modest hardware, a testament to its efficient design.

Sound and Music

WFTM has no sound or music. This is not an oversight but a deliberate omission. The game relies on text and player imagination to create its atmosphere. The silence can be eerie, especially during tense moments (e.g., when your champion is low on health and surrounded by enemies). It also reinforces the game’s minimalist ethos—every element serves a purpose, and anything extraneous is stripped away.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception

WFTM’s reception was muted. It was released as freeware with little fanfare, and its niche appeal limited its audience. On MobyGames, it holds a paltry 2.3/5 rating based on a single user review—a testament to its obscurity. Most players who tried it either loved its subversive humor or dismissed it as a gimmick.

Critics who did engage with the game praised its clever premise but noted its lack of depth. Without the tactile satisfaction of direct control, some found the experience frustrating. Others appreciated its brevity—each run lasts only a few minutes, making it easy to pick up and play.

Evolution of Reputation

Over time, WFTM has gained a cult following among roguelike enthusiasts. It is often cited as an early example of a “meta-roguelike”—a game that comments on the genre’s tropes while embracing them. Its influence can be seen in later titles like Dwarf Fortress (with its “Adventure Mode” god-like perspective) and Caves of Qud (which also plays with divine intervention mechanics).

However, WFTM remains a footnote in gaming history. It was never updated, and its Python-based code has not aged gracefully. Modern players may struggle with its lack of polish, but those who appreciate its humor and innovation still sing its praises.

Influence on Subsequent Games

While WFTM did not spawn direct sequels or imitators, its ideas have permeated the roguelike genre:

– God-Game Mechanics: Later roguelikes, such as Dungeons of Dredmor and Stone Soup, experimented with deity systems where players could earn divine favor.

– Meta-Commentary: Games like The Binding of Isaac and FTL: Faster Than Light embraced WFTM’s approach of using humor and satire to critique their own genres.

– Procedural Storytelling: WFTM’s focus on emergent narratives influenced games like RimWorld, where player agency is balanced with automated character behavior.

Conclusion: A Divine Experiment Worth Remembering

What Fools These Mortals is not a game for everyone. It is esoteric, minimalist, and unapologetically niche. But for those who appreciate its humor, its subversion of roguelike tropes, and its exploration of fate and free will, it is a hidden gem.

Strengths:

- Innovative Premise: The god-sim twist on the roguelike formula is fresh and engaging.

- Emergent Storytelling: Each run feels like a unique, often absurd tale of divine meddling.

- Humor and Wit: The game’s Shakespearean references and dry sarcasm make it a joy to read.

- Brevity: Runs are short, making it easy to play in bursts.

Weaknesses:

- Lack of Depth: The automated champion can feel frustratingly stupid at times.

- Minimalist Design: The ASCII graphics and lack of sound will not appeal to everyone.

- Niche Appeal: The game assumes familiarity with NetHack, limiting its audience.

Final Verdict:

7.5/10 – A clever, if flawed, experiment that deserves recognition for its bold ideas.

What Fools These Mortals is not a masterpiece, but it is a fascinating artifact—a game that dared to ask what it would be like to play as the god rather than the hero. In an era where roguelikes have become mainstream, WFTM’s subversive humor and meta-commentary feel more relevant than ever. It may not have changed the genre, but it certainly left its mark.

For roguelike fans and game historians, What Fools These Mortals is a must-play. For everyone else, it’s a curious footnote—a reminder that sometimes, the most interesting games are the ones that dare to be different.

“Lord, what fools these mortals be!” — And what fools we are to think we can control them.