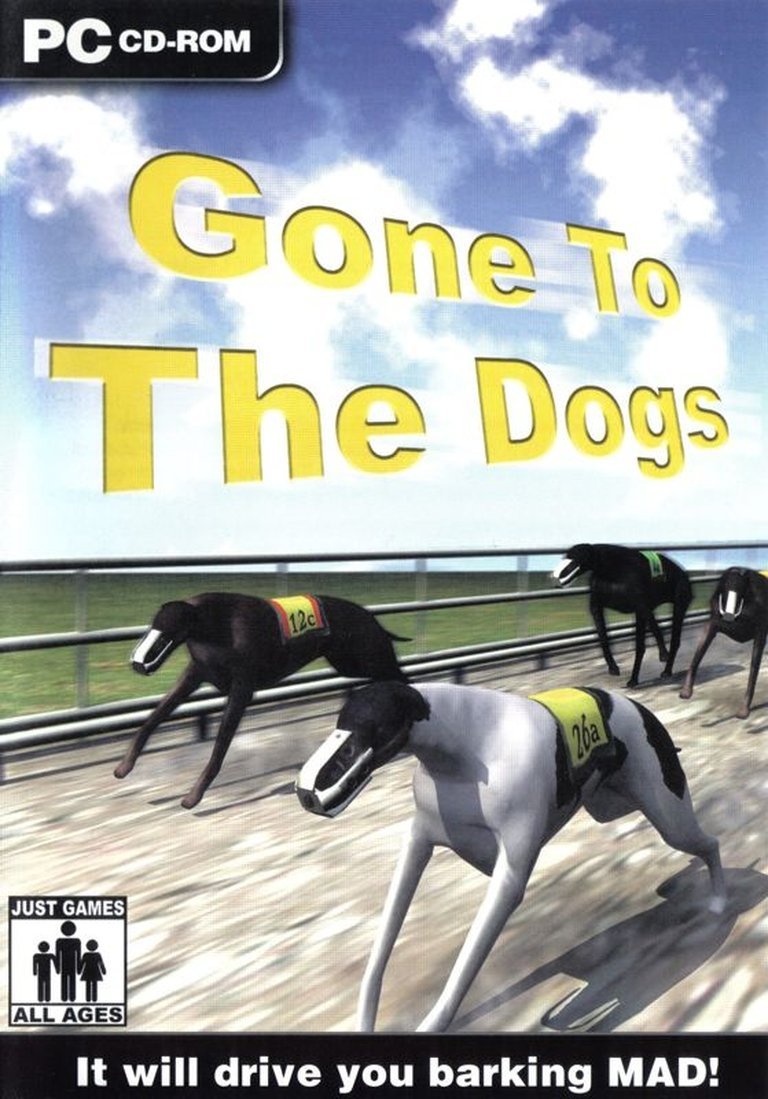

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Idigicon Limited

- Developer: Manyk Ltd

- Genre: Sports

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Betting, Management, Racing, Simulation

- Setting: Dogs, Gambling, Racing

- Average Score: 55/100

Description

Gone to the Dogs is a multiplayer sports simulation game released in 2005 where players bet on greyhound races. It features two modes: a normal game where players start with equal cash and bet on race winners or first/second place, and a ‘Race Night’ mode for organized group events. The game includes over 90 races with full video footage, commentary, and detailed form history for each dog, with the winner being the player who accumulates the most money.

Gone to the Dogs Free Download

Gone to the Dogs Guides & Walkthroughs

Gone to the Dogs: Review

Introduction

In the vast, often overlooked annals of video game history, certain titles emerge not as blockbusters or trendsetters, but as charming, idiosyncratic curiosities – digital artifacts that capture a specific moment or niche with surprising fidelity. Gone to the Dogs, released in 2005 by Manyk Ltd and published by Idigicon Limited, is precisely such a title. This Windows-exclusive sports simulation plunges players into the electrifying, chaotic world of greyhound racing, not as a jockey or trainer in the traditional sense, but as a gambler, a spectator, a participant in the visceral thrill of the bet. Its legacy is not one of widespread acclaim or industry-shifting innovation, but rather that of a cult classic, a faithful digital recreation of a specific cultural pastime that few games have attempted. This review argues that Gone to the Dogs, despite its simplicity and technical limitations, stands as a remarkably effective and atmospheric simulation of the greyhound racing experience, capturing the tension, strategy, and pure spectacle of the track with a dedication that belies its humble origins.

Development History & Context

Gone to the Dogs emerged from the British developer Manyk Ltd, operating within the specific market of budget and niche PC software publishers like Idigicon. The year of its release, 2005, placed it firmly within the era of DirectX 7 and Windows XP, a time when CD-ROMs remained a viable distribution medium for smaller titles, particularly those targeting established hobbies rather than mainstream gamers. The technological constraints are evident; the game required only a 500 MHz CPU, 64 MB RAM, and a 16 MB 3D video card – specifications that place it firmly in the realm of accessible, non-demanding software. This technical modesty was likely a deliberate choice, aiming for broad compatibility on the common home PCs of the mid-2000s and keeping development costs manageable for a niche title. The gaming landscape of 2005 was dominated by the rise of consoles (PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube) and the burgeoning PC market for immersive 3D shooters and RPGs. Within this context, a purely simulation-focused game about greyhound betting was profoundly niche, appealing almost exclusively to enthusiasts of the sport itself or those seeking a specific, low-key gambling experience. The game’s premise – multiplayer dog race betting with full video commentary – directly targets this specific audience, bypassing the need for broad mainstream appeal in favor of delivering a deep, authentic simulation of its chosen subject. The developer’s vision, as articulated in the game’s description, was clear: to provide a faithful recreation of the race night experience, complete with the form study, the betting mechanics, and the visceral thrill of watching the race unfold on screen.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

While lacking a traditional linear narrative with character arcs or overarching plot, Gone to the Dogs builds its thematic core around the fundamental concepts of risk, chance, competition, and the specific ritual of the race night. The “story” is the unfolding drama of each race meeting, driven by the players’ decisions and the unpredictable performance of the dogs.

The primary narrative driver is the economic simulation of the betting system. Players start with equal cash and must strategically allocate their funds across multiple races (typically nine, but customizable). The core tension arises from the constant calculation of risk versus reward: do you bet conservatively on a strong favorite to preserve capital, or gamble on a long shot for potentially massive returns? The two primary betting types – Win (picking the outright winner) and Place (picking first and second) – offer different risk profiles, adding layers of strategic depth. The dialogue is minimal but functional; it exists primarily within the race commentary, which provides color, analysis (“he’s coming up the rails!”), and results, framing the events within the context of a live broadcast. There are no named protagonists or antagonists; the competition is purely between the players themselves, their “characters” defined solely by their betting strategies and accumulated wealth.

Underlying these mechanics are potent themes. The most prominent is the thrill of gambling and the allure of the long shot. The game constantly tempts players with the dream of backing an unexpected winner and winning big, mirroring the real-world psychology of the betting shop. This ties into the theme of chance and the illusion of control. While players can study the “form” (recent race history) provided for each dog, the actual race outcome remains unpredictable, emphasizing the game’s core appeal: the suspense of the race itself. The ritual of the race night is another key element. The structured format of multiple races, the communal feel of the “Race Night” mode (implying a group gathering), and the presentation with full video and commentary evoke the atmosphere of a social event centered around sport and wagering. Finally, the theme of competition is distilled to its purest form: the player with the most money at the end of the meeting wins. This ruthless economic competition underscores the high-stakes environment the game simulates.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The gameplay loop of Gone to the Dogs is deceptively simple yet surprisingly engaging, built around two distinct but complementary modes:

-

Normal Game Mode: This is the core competitive mode for 1-8 players. Each player logs in, starting with an identical sum of cash. The session consists of a customizable number of races (default nine). In each race, players place their bets:

- Betting Types: Players can bet on the Winner (Win) or the First & Second (Place) finishers.

- Betting Flexibility: Crucially, bets are not restricted to fixed multiples (e.g., £5, £10). Players can wager any amount they can afford, allowing for highly personalized risk management. This flexibility is a significant strength, enabling strategies from cautious small bets to massive all-in gambles.

- Betting Interface: Players place their bets, indicating their chosen dog(s) and the stake amount. Once all bets are placed, the race is initiated.

- Race Execution: The race is presented as a full-screen video with live commentary. Players watch the dogs race, witnessing the unpredictable drama unfold. Commentary provides real-time updates and analysis.

- Resolution: After the video concludes, the results are displayed, showing the finishing order and calculating each player’s winnings/losses based on their bets and the race outcome. The player with the highest total cash after all races wins.

-

Race Night Mode: This mode shifts the focus to a simulated social event. It assumes a single “Event Organiser” manages betting for a larger group of people (potentially spectators). The organiser selects races as needed and manages the betting process, presenting the races on screen for the group to watch and bet upon. This mode emphasizes the communal, event-like atmosphere of a real greyhound race night.

Core Systems:

* Race Database: The game boasts an impressive collection of over 90 unique races, each with its own specific set of competing dogs.

* Form Analysis: A key strategic element is the “form” provided for each dog in every race. This includes details like recent race history, performance stats, and potentially the dog’s name or number. Studying this form is essential for informed betting, adding a layer of simulation and authenticity.

* Progression/Competition: Progression is purely economic and competitive. There is no character progression for the dogs or the player’s avatar beyond increasing (or decreasing) their bankroll. The goal is simply to finish with more money than your opponents.

* UI: The interface is functional and minimalist, designed for clarity in the betting and results phases. While lacking visual flair, it efficiently serves its purpose of placing bets and displaying race information and results.

Innovation/Flaws:

* Innovation: The most significant innovation is the integration of full race video with live commentary. This was relatively uncommon for budget simulation titles in 2005 and provides a level of immersion and authenticity that simple text or animated graphics couldn’t match. The flexible betting system is another strong point, offering greater player agency than fixed-bet games.

* Flaws: The primary limitation is the lack of depth beyond the betting simulation. There are no dog training, breeding, or stable management elements found in other “tycoon” or simulation games. The graphics, while adequate for the video playback, are otherwise very basic for the time. The repetitiveness of the core loop (bet, watch race, repeat) can set in over multiple meetings. The reliance on pre-recorded video also limits the dynamism of the races; while the outcomes are random, the visual presentation is static.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Gone to the Dogs is meticulously confined to the greyhound racing track. There is no exploration of a broader city, countryside, or kennel complex. The setting is the oval track itself, the grandstand, and the betting area. This focused scope is a deliberate choice, immersing the player entirely in the specific environment of the race meeting.

Visual Direction:

* Race Footage: The centerpiece is the full video footage of the races. While the source material doesn’t specify the exact quality, the description implies it’s clear enough to follow the dogs’ positions and movements. The camera likely provides a standard trackside or overhead view, typical of televised greyhound racing. This footage, combined with live commentary, is the primary source of visual atmosphere, conveying the speed, the close finishes, and the sheer spectacle of the dogs chasing the lure.

* Presentation: Screenshots (where available, though not provided here) likely show a simple, functional interface for placing bets and displaying results. The overall aesthetic is likely clean and uncluttered, prioritizing the visibility of race information and the video playback over elaborate graphical design. The “form” screens would present dog statistics in a clear, readable format.

* Atmosphere: The visuals, particularly the race footage, aim to capture the kinetic energy and tension of live racing. The focus is on the dogs in motion, the lure, and the immediate environment of the track. The lack of extraneous environments reinforces the singular focus on the race event itself.

Sound Design:

* Commentary: The live commentary is arguably the most crucial audio element, described as “full race commentary.” This provides the essential narrative and excitement, calling the action, describing the dogs’ performances, building tension during the run-up, and announcing the results. A skilled, enthusiastic commentator is key to replicating the authentic broadcast experience.

* Ambiance: While not explicitly detailed, one would expect ambient sounds of the track: the starting boxes opening, the yelps of the dogs, the buzz of the crowd (if simulated), and the mechanical sound of the lure. These sounds would work in tandem with the commentary to create a believable race night atmosphere.

* UI Sfx: Simple sound effects for placing bets, confirming selections, and displaying results would provide necessary audio feedback for the player actions.

The combination of the live race video and dynamic commentary is the primary tool for building atmosphere, successfully transporting the player into the specific world of a greyhound race meeting, focusing entirely on the spectacle and the stakes of the competition.

Reception & Legacy

Gone to the Dogs occupies a peculiar place in the annals of gaming reception and legacy, defined by its extreme niche nature and the lack of mainstream critical attention.

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch:

* Critical Silence: As evidenced by the MobyGames entry and Metacritic page, Gone to the Dogs received no significant critical reviews upon its 2005 release. This is typical for titles targeting such a specific hobbyist market. Gaming publications focused on mainstream action, adventure, or strategy titles would have little reason to cover a simulation dedicated solely to greyhound betting. The MobyGames “Moby Score” is listed as “n/a,” reflecting the absence of aggregated professional reviews.

* Player Reception (Post-Launch): While contemporary player reviews are scarce, evidence from later platforms and fan communities (like Kongregate comments on the Flash version) suggests a mixed but generally positive reception among its target audience. Comments praise the authenticity of the racing experience, the excitement of the betting, and the quality of the video/commentary. Common criticisms, often voiced regarding the Flash version, include the short length and repetitive nature of the core loop. However, for enthusiasts of the sport or gambling simulations, these might be seen as acceptable trade-offs for the focused experience.

* Commercial Performance: Its commercial performance remains unrecorded and likely modest. Published by the budget-focused Idigicon and targeting a niche market, it was unlikely to achieve blockbuster sales. Its survival on platforms like MyAbandonware and the Internet Archive suggests it found a sufficient, albeit small, audience to sustain its presence in the budget gaming landscape.

Evolution of Reputation and Legacy:

* Niche Cult Classic: Over time, Gone to the Dogs has solidified its reputation as a cult classic within the niche genre of sports simulations and gambling games. It’s remembered not for pushing boundaries, but for its unwavering dedication to faithfully simulating the specific experience of a greyhound race night. The combination of accessible betting mechanics and the unique inclusion of full race footage with commentary makes it stand out among more abstract gambling games.

* Influence: Its direct influence on the wider gaming industry appears minimal. It didn’t spawn a major franchise or inspire widespread clones within the mainstream. However, its existence points to a category of dedicated hobbyist simulations. Its spiritual successor in terms of developer output is arguably the Flash game “Racehorse Tycoon” by robotJAM (Shockwood Games), which shares a similar tycoon/simulation approach focused on animal racing. The existence of a Flash version (2010) by robotJAM, developed separately, indicates the enduring appeal of the core concept and its suitability for the casual browser game market, reaching a different audience than the original CD-ROM release.

* Preservation and Accessibility: The game’s survival on platforms like MyAbandonware, the Internet Archive (with a note on 64-bit compatibility issues requiring a VM), and its inclusion in various “abandonware” collections highlights its value as a historical artifact of budget PC gaming and a specific sporting subculture. It serves as a time capsule of mid-2000s simulation software.

Conclusion

Gone to the Dogs is not a game that redefines gaming or sets new technical benchmarks. It is, however, a remarkably successful and authentic simulation of its chosen subject: the visceral, strategy-laden, and socially charged world of greyhound race betting. Released in 2005 by Manyk Ltd and Idigicon, it embraced the technological constraints of its era to deliver a focused experience centered on two key innovations: the inclusion of full race video with live commentary and a flexible, non-fixed betting system. While lacking the depth of a broader “tycoon” simulation, it excels in its niche, capturing the tension of form study, the thrill of the unpredictable race, and the pure economic competition of the betting pool. Its narrative is woven from the drama of each race meeting, driven by player risk and chance.

Its reception was muted in the mainstream press, but it has since achieved a well-deserved status as a cult classic among enthusiasts of sports simulations and gambling games. Its legacy lies in its unwavering dedication to authenticity and its unique presentation, setting it apart from more abstract betting games. While the lack of character progression or training systems limits its longevity for some, its core loop of betting, watching, and competing remains compelling. Gone to the Dogs stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of deeply focused simulations, preserving a specific cultural pastime with charm and surprising effectiveness within the vast, sometimes overwhelming, landscape of video game history. It is, in essence, a faithful digital kennel, capturing the bark and the bite of the greyhound track.